“The scientists says that electricity is life. Then Jackson Park is of a truth a living thing.”

— H. D. Northrop, The World’s Fair as Seen in One Hundred Days (1893)

A crowd of fans sporting blue and red poured out of the new Franklin Field in Philadelphia on the first day of October in 1895, a warm and sunny start to the college football season. Elated with the Quaker’s 40–0 victory over the visiting team from Swarthmore College, students spread across the University of Pennsylvania campus. Those passing in front of the library building recoiled at the disgraceful sight of the famous American statesman, eminent scientist, and their university’s founder—a decaying and decapitated statue of Benjamin Franklin.

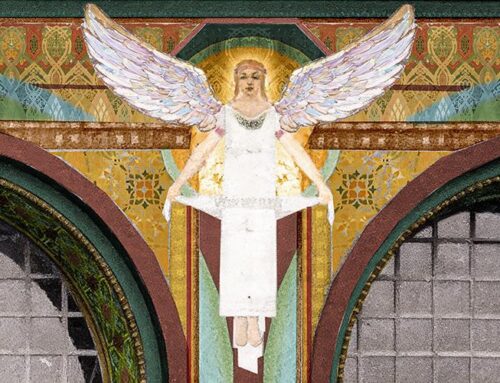

Carl Rohl-Smith’s Benjamin Franklin, described as “one of the finest pieces of statuary on the grounds” of the 1893 World’s Fair, stood in the portico of the Electricity Building. [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894.]

There he stands

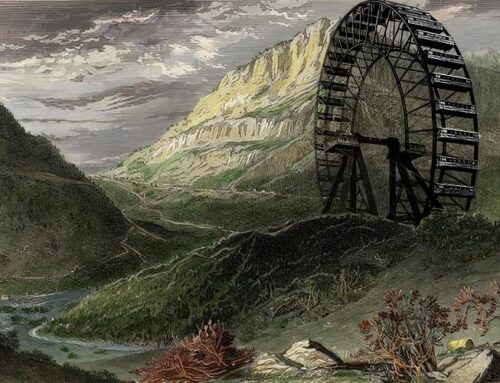

Two years earlier, this Benjamin Franklin sculpture held a lofty position on the fairgrounds of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Franklin oversaw an electric exposition. The entire fairgrounds crackled with the novelty of it: an electric train circled the White City on an elevated track while electric launches glided around the lagoon below. Electric fountains created giant sprays of water illuminated by colorful electric lights at night. On the Midway Plaisance, electric motors made ice for a skating rink and railway and turned a giant observation wheel. Nowhere was the promise of the electric age more exquisitely displayed than inside the Electricity Building in front of which stood the statue of Benjamin Franklin.

One Columbian Exposition historian described the scene:

“Upon approaching the Electricity Building from the south the visitor beholds on a pedestal in the hemicycle the towering statue of Benjamin Franklin, the first one to attempt to harness lightning to thought. There he stands, and there is no mistaking him, in his long-tailed coat and old Knickerbocker habiliments throughout. Nor is there any mistaking of the exact moment of the philosopher’s life, for the artist has so conscientiously and dramatically reproduced these that nothing is wanting in the conception. The uplifted face and eyes, the half-outstretched hands, the look of eager anticipation are all faithfully delineated. Every American school child that gazes upon it knows that it is old Ben Franklin and his kite and that he has wrested from the clouds the secret of their lightnings—that he has discovered electricity.”[Truman 355]

Appropriate for the building it decorated, the statue celebrated Franklin’s seminal experiment 131 years earlier when, on June 10, 1752, he launched a kite into a Philadelphia thunderstorm and collected ambient electrical charge in a Leyden jar, enabling him to demonstrate the connection between lightning and static electricity.

Most of the sculptural program of the Columbian Exposition comprised works showing either North American native animals or allegorical human figures representing the American republic. Only a handful of statues decorating the fairgrounds depicted historical people—among them Caesar, Daniel Boone, and (of course) Christopher Columbus—and few were as instantly recognizable to visitors as the founding father flying his kite in front of the Electricity Building.

This is the story of how Benjamin Franklin came to stand on a pedestal at the World’s Fair, then travel “home” to the university he founded before finally suffering an ignoble demise.

Danish-American sculptor Carl Rohl-Smith (1848–1900). [Image from Literary Digest May 26, 1894.]

A pleasant-faced Dane

The honor of sculpting America’s treasured statesman for the 1893 World’s Fair went to an immigrant, Carl Rohl-Smith.

One American who met him described the sculptor as a “brown-eyed, pleasant-faced Dane … in manner retiring almost to diffidence, but with an open, frank countenance and directness of speech which cannot fail to impress one with his sincerity,” adding that “I think he would be called slow, possibly plodding, but certainly honest and thorough in the smallest detail.”[Jennings] Another visitor to his studio seemed charmed by his soft and insinuating voice, reporting that his manner had “a medieval fervor that is irresistible.”

Born in Roskilde, Denmark, on April 3, 1848, Carl Wilhelm Daniel Rohl-Smith studied at the Royal Academy of Arts in Copenhagen under Danish sculptor Herman Vilhelm Bissen (1798–1868). (Bissen exhibited two works in the Palace of Fine Arts at the 1893 World’s Fair, and displayed his sculpture Shepherdess in the Danish Pavilion within the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building.)

After graduating from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 1869, Rohl-Smith honed his skills working across Europe for several years, with Albert Wolff in Berlin, and in Vienna, Rome, and Paris. His sculptural output included ornamentation of the New Parliament House at Vienna and the beautiful Marble Church in Copenhagen, and the adornment of parks and public places in Denmark and Germany. Rohl-Smith earned fame for his bronze statue of the Greek mythological hero Ajax, for which won an Honorable Mention at the 1878 World’s Fair in Paris. The work, commissioned for the second Christiansborg Palace in Copenhagen, was lost in 1884 when a fire destroyed the palace. His Benjamin Franklin sculpture for the 1893 World’s Fair earned a comparison to this earlier Ajax (see below).

Rohl-Smith accepted a position as an art professor at the Copenhagen Academy and married his wife Sara before moving to the United States in 1886 in search of better opportunities. “In Denmark, his emigration was regarded as a loss to the art of his country,” noted an 1891 profile. [“Carl Rohl-Smith”] While working in New York City he prepared bas-relief sculptures and busts for famous people and as memorials. His 1887 bronze medallion sculpture of Mark Twain earned praise from his subject, who claimed that the artist modeled “exact to the life.” [Bak 71] Publicity for Rohl-Smith as he prepared his 1893 World’s Fair sculpture claimed that “Mark Twain certifies to a personal knowledge of the sculptor’s skill.” [“Carl Rohl-Smith”]

The sculptor moved to Louisville, Kentucky, in 1889. His important works at this time included a bronze statue of Kentucky Superior Court Judge Richard Reid and Heroes of the Alamo Monument (1891) for the Texas State Capitol in Austin. Rohl-Smith’s Bust of Young E. Allison depicted his friend, a Kentucky writer and newspaper editor who later wrote a glowing profile of the artist as he prepared his Franklin statue in Chicago (see below).

Rohl-Smith moved to Chicago in 1891, joining the mass migration of artists and architects drawn for work with the upcoming World’s Columbian Exposition, and maintained an office in room 1301 of the Woman’s Temple building on LaSalle Street in downtown Chicago. “Mr. Rohl-Smith has secured the applause of all the critics who have written on his works,” wrote Illustrated World’s Fair in 1891. “The New York Sun has singled him out for its applause. At Louisville, Kentucky, he did much great work. He is a gain to the World’s Fair, and his figures cannot fail to dignify as well as embellish the buildings.” [“Carl Rohl-Smith”]

Detail from a prospectus of Van Brunt & Howe’s Electricity Building, showing a planned statue of Benjamin Franklin in a position of honor at the south entrance. [Image from the Inland Architect and News Record April 1891.]

The spirit of the idea

The Kansas City architectural firm of Van Brunt & Howe designed the Electricity Building, when was erected on the northwest side of the Grand Basin with its front entrance facing south towards the Administration Building. Carl Rohl-Smith, having gained a reputation in the Midwest for his work, secured the commission from the Columbian Exposition for the statue of Benjamin Franklin to be erected in the niche of the building’s grand south pavilion. By July 31, 1891, he had a contract for $3000. While the sculptor was assigned his subject, “the·design itself, the spirit of the idea, was left to him” [Allison 828] Benjamin Franklin would be his first great public work in America.

In addition to his building decoration, Rohl-Smith also engaged with the Fine Art Department of the Exposition. He had two works accepted for the United States sculpture display. His plaster bust of Mato Wanartaka (Kicking Bear), Chief of the Sioux (1892) depicted the Mniconjou Lakota chief who attended the 1893 World’s Fair as part of the adjacent Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. A bronze casting is in the collection of the Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK), the National Gallery of Denmark. His bronze Bust of Henry Watterson (1890), lent to the Exposition by Mrs. Henry Watterson of Louisville, currently is held in the Kentucky History Collection of the Louisville Free Public Library.

Rohl-Smith exhibited two sculptures in the Palace of Fine Arts at the 1893 World’s Fair. Mato Wanartaka (Kicking Bear), Chief of the Sioux (1892) [Image from the Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK), the National Gallery of Denmark] and Bust of Henry Watterson [Image from the Kentucky History Collection of the Louisville Free Public Library.]

A photograph of Rohl-Smith’s clay model for the Benjamin Franklin statue. [Image from Unsere Weltausstellung. Eine Beschreibung der Columbischen Weltausstellung in Chicago, 1893. Fred. Klein Co. 1894.]

True and godlike

Only two months after receiving his commission, Rohl-Smith was nearing completion on his clay model of Franklin in October 1891. His statue received official approval by November 2, 1891.

John McGovern, editor of the Illustrated World’s Fair in Chicago, visited the artist in his studio in the fall of 1891 and reported to be “delightedly shocked with the heroic clay statue of Franklin.” He described his meeting the Danish sculptor:

“I ask about his name. Is he Smith, or Rohl-Smith, like Goldsmith. It is the latter way. I tell him his statue is magnificent I forget the everlasting white and the silent tan-bark outside. I whistle to him out of Valentine in the fourth act of Huguenots, to explain to him that his statue is true, and godlike. It is all clear to him. We raise our hats to each other; we clasp each other’s hands, he offering his wrist, but I honored as much with the clay of his art as the clay of his flesh. I go forth much renewed and blessing that Danish sculptor.” [McGovern (1891)]

The sculptor confessed to McGovern that “his eyes no longer measured correctly, so often had they dwelt upon the loved object of his toil.” [McGovern (1892)] Photographs of the clay model made around this time began to circulate in the national press.

Rohl-Smith working on his enlarged plaster sculpture of Benjamin Franklin. Note the small maquette standing at the base. [Image from the Illustrated World’s Fair Oct. 1891.]

The real artist

The enlargement of the model to the approximately fifteen-foot tall figure was made in “staff,” a mixture of plaster and hemp or jute fibers that when wet could be applied onto armatures and dried hard. Nearly all the outdoor sculptures on the fairgrounds (as well as most building exterior surfaces) were made of this convenient material that allowed for rapid production of sculptures. The trade-off for speed, alas, was durability. Benjamin Franklin only needed to last only for the six months of the Fair. Anything more was borrowed time. Almost all staff sculptures (and building exteriors) on the fairgrounds were painted white to give the appearance of marble. Although pre-Fair reports noted that the Franklin statue would be “colored to imitate bronze,” [“Franklin Statue Raised”], the final work was white.

As with several other sculptures on the fairgrounds of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, Benjamin Franklin came into form by the hands of women whose work went largely unrecognized at the time. According to the final report of the Superintendent of Buildings W. D. Richardson, assisting Rohl-Smith in his work on the Franklin statue was Miss Enid Yandell. A native of Louisville, Kentucky (though not living there during Rohl-Smith’s time in that city), she was among a group of women sculptors known as the “White Rabbits” organized by sculptor Lorado Taft to work on various statue and sculptural decorations to buildings. Yandell also designed and carved the caryatids that supported the roof garden of the Woman’s Building. After the 1893 World’s Fair, she studied with Auguste Rodin in Paris, and with Philip Martiny and Frederick MacMonnies in the U.S.

Also contributing to the Benjamin Franklin sculpture was Carl’s wife, Sara Rohl-Smith. Obituaries at the time of her death in 1921 noted that the couple collaborated on the 1893 statue and that her sculptor husband “always asserted his wife was the real artist and he was only the workman.” [“Death in Copenhagen …”] Mr. and Mrs. Rohl-Smith completed Franklin by the time Francis Millet assumed the position of Director of Color and Functions on June 1, 1892.

The massive grandeur of Van Brunt & Howe’s Electricity Building at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, showing Carl Rohl-Smith’s Benjamin Franklin statue in the niche of the south pavilion. [Image from Arnold, C. D.; Higinbotham, H. D. Official Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Press Chicago Photo-gravure Co., 1893.]

Stands without a rival

On March 6, 1893, in the nation’s capital, a group of representatives from the World’s Columbian Exposition met with President Grover Cleveland to formally invite him to officiate the Opening Day of the World’s Fair. On the fairgrounds in Chicago that day, the colossal plaster statue of Benjamin Franklin took its place at the grand entrance of the Electricity Building. The sculpture stood upon a sixteen-foot-high pedestal (then-unfinished) inside the niche of the south pavilion, a hemicycle 78 feet in diameter and 103 feet high with a half dome for its roof. A semi-circular arch framed the opening and was crowned by an ornate pediment and surmounted by an attic, the whole south face reaching a height of 142 feet.

“From either standpoint, that of massive grandeur or simply beautiful effect, the great south entrance to the Electricity Building stands without a rival among all the noble portals of the Exposition structures,” wrote one Columbian Exposition souvenir album about the spot where Franklin greets the visitor.

“There are some which make a more pretentious display and are more conspicuous for elaborate decoration, but none can offer such a combination of beauty and imposing grandeur as this entrance from the Grand Plaza, where stands Benjamin Franklin with the kite in one hand and in the other the key with which he unlocked the mystery of the lightning … a heroic, striking figure, among all the groups and single figures in the White City.” [Photographs … 87]

Architect Henry Van Brunt explained his vision for the grand entrance to his building:

“The most famous and most cherished association of America with the history of the science of electricity is the discovery of the electric properties of lightning by Franklin. The architects determined, therefore, that a statue of the patriot-philosopher should stand under this great arch, and that to him the main porch on the court should be dedicated … [his] conception of the subject is happily realized in a spirited figure … This noble statue is elevated on a high pedestal in the center of the porch, and behind and over it is formed a colossal niche, of which the triumphal arch is the frame, covered with a half dome or conch, divided by ribs, and profusely enriched with bas-reliefs, recalling, in general aspect, the much admired hemicycle or belvedere in the court of the Vatican palace, and, in detail the characteristic stucco embellishments in the vaults of the Villa Madama”[Van Brunt 544]

Running beneath the cornice of the building were the names of Franklin and another forty eminent scientists who experimented with electricity: Galvani, Ampere, Faraday, Ohm, Sturgeon, Morse, Siemens, Davy, Volta, Henry, Oersted, Coulomb, Ronald, Page, Weber, Gilbert, Davenport, Soemmering, Don Silva, Arago, Damill, Jacobi, Wheatstone, Gauss, Vail, Bain, De la Rive, Joule, Saussure, Cooke, Varley, Steinheil, Guericke, La Place, Channing, Priestley, Maxwell, Coxe, Thales, and Cavendish. On the wall behind Franklin, an epigram read: “ERIPUIT COELO FULMEN SCEPTRUMQUE TYRANNIS” or “He snatched the lightning from the heavens—the scepter from tyrants.

Rohl-Smith’s Benjamin Franklin statue was placed on a very high pedestal that, for some critics, made it difficult to admire. [Image from a glass slide produced by William H. Rau of Philadelphia from the University of Michigan Lantern Slide Collection.]

Strikingly appropriate for the place it is to occupy

“Heroic in size and masterful in conception, it appears as a sentinel guarding the entrance to the great building,” reported World’s Columbian Exposition Illustrated. [Campbell 267] The completed Franklin statue was between fourteen and sixteen feet tall (the difference may be due to whether the base he stands on is included), or about two-and-a-half times life size. The pedestal was reported to be anywhere from fourteen to twenty-one feet high; photographs indicate the latter. Criticisms of this display height began the day of the installation when the Tribune reported that “the pedestal is too high to show the statue to the best advantage.” [“Franklin Statue Raised”] One exposition souvenir album suggested that Rohl-Smith agreed, writing that “the sculptor believed the authorities raised his work upon a pedestal too high for the best effects.” [Dream City] At least one visitor, however, felt impressed by the effect, writing that the “statue occupies a commanding position and is very imposing as seen from the open space in front of it.” [“World’s Fair Letter”]

“Representing Franklin, as it does, actually conducting the lightning to the earth in his well-known experiment with the kite in Philadelphia,” wrote Scientific American, “there could not well be found a subject more strikingly appropriate for the place it is to occupy, in front of the spacious edifice to be devoted to the display of electrical appliances.”

“The work is admirably suggestive and strong; and it has appropriate station at the portals of the hall in which are displayed the marvelous results following upon such primitive experiments as his; for as he stood upon the threshold of discovery of the most profound and valuable of Nature’s secrets.”[Cameron 318]

Kentucky journalist Young E. Allison praised “the poise that sculptors dream about and few achieve” in Rohl-Smith’s Benjamin Franklin statue. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

An element of his genius

The sculptor’s Kentucky friend Young E. Allison, commenting on photographs that were made of the clay model, offered generous praise. He highlighted “the force and breadth of a conception which has lost nothing in the execution,” writing that the work contained “a concentrated power so often seen in the rough sketch, yet which the most patient artist finds it difficult to preserve in the finished figure.” Allison continued:

“The figure represents Franklin, with his kite and cord in hand, in the midst of a gathering storm, watching for the moment when he was to send that kite up and bring down from the flashing skies the brilliant and important message to science that lightning was identical with the electric fluid. It requires no effort to see that the sculptor has rendered the idea in a most graphic and dramatic and yet in a perfectly simple and natural manner. … There are few sculptors who have, in anything like the degree possessed by Rohl-Smith, the capacity to represent intense action without straining. It is an element of his genius apparent in almost every work he has executed; but it is when observed in such a great figure as this, that its admirable quality can best be judged. It lends a stirring realism to the effect and produces an impression at a glance which no amount of closer study can obliterate. There is no rest in it, yet there is no strain; he has caught the well poised and critical instant when intellectual propulsion is about to manifest itself in physical effort. And this is the poise that sculptors dream about and few achieve. There is, moreover, in the work a triumph over the classical idea that the sculptured figure or group must be complete in itself without exterior objects contributing to the ‘story,’ on the theory that such contributing objects must be pointed out, and their absence therefore detracts from the work. With ‘Franklin’ written under Rohl-Smith’s statue even a school-boy might tell the story and see without suggestion the flashing clouds into which the eyes are peering with the desire to drag their secret to earth. There will be no art work of a realistic character at Chicago which will surpass this statue of Franklin. It is the best representation by art that has yet been made of that homely old anecdote of how the blunt philosopher ‘drew the lightning from the skies,’ and Rohl-Smith has rendered it with epical suggestion.” [Allison]

Historian Hubert Howe Bancroft concurred, describing this Franklin as “one of the best conceptions ever presented of the great discoverer, his gaze turned upward toward the lowering clouds, in one hand the kite, and in the other the key of which all the world has read.”[Bancroft 403] Other reviews described it “as expressive and impressive as any sculptured figure on the grounds” and “a sculptural work of great strength.”

Writing that “sculptor Carl Rohl-Smith … had for his inspiration one of the most dramatic subjects in American history,” the guidebook Rand, McNally & Co.’s A Week at the Fair offered this description of the sculpture:

“Grasping with one hand his kite, which rests upon the ground, the other holds aloft the key with which this greatest of all nature’s mysteries was unlocked. His head is thrown back. Glorious in its triumph appears the face, as if still searching the heavens, and the whole pose is one of mastery and power. While some critics have pronounced the statue overdrawn, all agree that it is full of freedom and power, and, considered in regard to its heroic surroundings as well as to the requirements of the plastic art, it is certainly one of the finest pieces of statuary on the grounds.” [Rand, McNally & Co.’s A Week at the Fair 83]

The criticism of Rohl-Smith’s design being “overdrawn” likely is refers to this review by architectural critic Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer of the New York World:

“The station is a superb one, and the subject unsurpassed, among all American subjects, for historical interest and dramatic suggestiveness. But in trying for dramatic effect the sculptor, Mr. Carl Rohl-Smith, who, I am told, is a Danish-American, has fallen into melodramatic over-emphasis, although of a more robust and masculine sort than that which marks the work of the Viennese sculptor, Mr. Bitter. Franklin holds in one hand his kite, which rests upon the ground, and in his other uplifted hand the historical key. But his body and head are thrown back and he is gazing into the air in a pose which makes us feel that he is trying to play the role of Ajax rather than his own. He seems not to be searching the heavens, but to be defying them, and also to be less intent upon mastering his problem than upon impressing spectators with the fact that he is equal to mastering any problem.” [Van Rensselaer]

The dramatic pose of Benjamin Franklin, with head thrown back as if still searching the heavens, received a great deal of commentary from critics and visitors. [Image from Art Treasures from the World’s Fair. The Werner Company, 1895.]

The attitude is striking

Several commentators examined the choice of Franklin’s posture, with his head thrown back. One guidebook described the stance as “posed as if demanding of the clouds the revelation of their secrets, guarding its entrance and giving the keynote to the character of its exhibits.”

Describing the selected pose as “admirable,” Henry Davenport Northrop wrote that …

“Franklin stands firmly planted upon his feet, his coat with full skirts blown back by the wind in which he is flying the historic kite. His head in an attitude of expectancy, is inclined backward, while his face absorbed in thought is watching the experimental flight. One hand holds the key, the other the silken string of the kite.”[Northrop 250]

“The attitude of the figure is striking,” James B. Campbell wrote:

“The artist seems to have caught the inspiration at a time when the great philosopher was making the experiment of his life. He is in the act of flying the kite and stands in an attitude of expectancy. His face is turned toward the sky as if waiting a discharge of electricity from the clouds, that he may have an opportunity to prove his theory. The whole figure is commanding and will attract the attention of the visitor approaching the grand entrance to the Electricity building.” [Campbell 267]

Not everyone agreed. Julian Hawthorne related that his companion Hildegarde commented as they exited the Electricity Building: “Oh, that arched and domed entrance is one of the great things at the Fair, though I don’t like the statue of Franklin; I don’t believe he ever stood with his head thrown back in that French sort of way.” [Hawthorne 89]

One commemorative volume offered this interesting analysis of the plaster Franklin’s appearance:

“He is a larger, more portly and more imposing personage than our fancy leads us to picture Benjamin Franklin, whom we are apt to recall as the wit and as the shrewd originator of Poor Richard’s homely wisdom, forgetting his more important character of a patriot, a wise and far-seeing statesman, and one of the greatest of scientific discoverers … The sculptor has lost no opportunity of showing that his hero is placed out of door in close communion with nature. His hair,—those venerable locks which the sturdy Quaker never would powder or dress according to the taste of the day,—flies in the wind, accompanied by pocket flaps, coat tails and lapels. It is a figure full of life and vigor.”[Art Treasures 69]

A drawing of the Franklin sculpture clearly shows a kite string draped from the figure’s left hand down to his right foot. [Image from Hitchcock, Ripley The Art of the World Illustrated in the Paintings, Statuary, and Architecture of the World’s Columbian Exposition. D. Appleton, 1895.]

The moment before the storm

Many images of the clay model depict a kite string draped from Franklin’s left hand down to his feet. It is not clear of this survived in the final plaster enlargement. William E. Cameron provided this historical perspective on dress and apparatus:

“The figure is clad in colonial garb, is sturdily posed, the attitude that of thought which has caught sight of the solution of the problem. The hands hold the rude implements with which he conducted the mysterious current from the clouds,—the key, silk kite-cord, and umbrella which were the forerunners of the elaborate and intricate contrivances that chain and utilize the lightnings now.” [Cameron 318]

About Franklin’s dress, another commemorative volume stated: “The garb of colonial times in which the figure is arrayed, with its long-skirted coat, its knee breeches, buckled shoes and ruffles lends itself better to the requirements of art than the utilitarian dress of today.” [Art Treasures 69]

The scientist’s pose, implements, and dress all contributed to the drama of the storm. “The figure is full of strength and the treatment of the drapery and the pose are free and vigorous,” wrote the Chicago Tribune on the day the statue was installed, adding that “the storm is finely indicated by the windblown hair and drapery.” Allison agreed, noting that “there is the mark of the storm in the blown drapery and locks; there is the look of keen and eager suspense in the face, and the figure is poised at the moment of intense mental and physical activity in repression.” [Allison]

Charles Graham’s watercolor After Night in Front of Electrical Building of showing the Franklin statue illuminated. [Image from Graham, Charles S. The World’s Fair in Water Colors. Mast, Crowell & Kirkpatrick, 1893.]

A blaze of splendor

Viewing the heroic lightning catcher in the evening brought even greater rewards. “The great statue of Franklin at the portal of the Electrical building rests in a blaze of splendor,” advised one guidebook.[Flinn 14] Electrical illumination of Benjamin Franklin at night sparked wonder an awe among visitors to the fair. One described the night scene this way:

“Near the surface of the water runs a line of incandescent lamps, which gleam and are reflected like jewels, and every now and then the search-light is thrown upon the different groups of sculptures in a way that emphasizes their beauty. As it fell on the spirited figure of Franklin standing in the arched recesses of the Electrical Building, the bold lines of the composition were clearly revealed, while the fine figures of animals on their high pedestals along the water seem almost life-like in distinctness. The spectacle was wonderful.” [Robbins 294]

“In this strange light the statues of men and animals look like ghosts,” explained one commemorative book, “unwittingly drawn down to view a weird and wondrous scene, and in the grand portal of the Electricity Building, the upturned face of the Franklin statue seems to smile back thanks to God for this marvel, that he had but dimly discerned when he first called the lightning from the clouds.”[Shepp 56]

Alas, the magical spell cast by the Dream City was not meant to last. Not long after the World’s Fair closed on October 30, 1893, the countless exhibits from about fifty nations began to scatter around the world, a few buildings were relocated, and many more eventually succumbed to the ravages of fire. Although a few of the plasters were used to make cast bronze castings, nearly all of the spectacular decorative artwork—murals, ornaments, and sculptures—was lost. Carl Rohl-Smith’s statue of the sturdy Quaker would be no exception, and the Chicago Tribune had anticipated as much on the day it was installed on the fairgrounds, writing: “In looking at it, the chief regret is that it should be cast in a material so fragile that it is not to be a lasting monument.” [“Franklin Statue Raised”]

Unlike most of the other World’s Fair sculptures, however, Benjamin Franklin had a second act.

This photograph of the loggia of the Electricity Building shows the scale of the Benjamin Franklin statue and pedestal relative to a person seated at the base. [Image from American Architect and Building News, April 14, 1894.]l

SOURCES

Allison, Young E. “The Franklin Statue” Engineering Magazine Mar. 1892, pp. 827–29.

“Art Notes” New York Times Oct. 26, 1891, p. 4.

Art Treasures from the World’s Fair. The Werner Company, 1895.

Bak, Aase “He Came He Saw He Conquered” The Bridge, 1986, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 68–76.

Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.

Burnham, Daniel H. Final Official Report of the Director of Works of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume IV.

Cameron, William E. The World’s Fair Being a Pictorial History of the Columbian Exposition. P.D. Farrell, 1893.

Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume I. M. Juul & Co., 1894.

“Carl Rohl-Smith” Illustrated World’s Fair Oct. 1891, p. 76.

“Death in Copenhagen of Mrs Sara Rohl-Smith” Boston Globe Aug. 17, 1921, p. 2.

The Dream City. A Portfolio of Photographic Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition. N. D. Thompson, 1893.

“Exposition Notes” Chicago Tribune Nov. 3, 1891, p. 7.

Flinn, John J. The Best Things to Be Seen at the World’s Fair. Columbian Guide Company, 1893.

“Franklin Statue Raised” Chicago Tribune Mar. 7, 1893, p. 8.

From Peristyle to Plaisance or the White City Picturesque Painted in Water Colors by C. Graham Together with a Brief Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago 1893. Part One. Winters Art Litho Co., 1894.

Hawthorne, Julian. Humors of the Fair. E.A. Weeks, 1893.

“How the Big Fair Grounds Look” Philadelphia Inquirer Oct. 16, 1891, p. 5.

Jennings, Janet “Our Washington Letter” The Independent Jun. 18, 1896, p. 6.

Johnson, Rossiter A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Held in Chicago in 1893, Volume 2: Departments. D. Appleton and Co., 1897.

McGovern, John “In Jackson Park” Illustrated World’s Fair Jan. 1892, p. 122.

McGovern, John “The Playthings of a Planet” Illustrated World’s Fair Nov. 1891, p. 3.

Northrop, H. D. The World’s Fair as Seen in One Hundred Days. Ariel Book Co., 1893.

Photographs of the World’s Fair. Werner Co., 1893.

Rand, McNally & Co.’s A Week at the Fair. Rand, McNally & Co., 1893.

Robbins, M. C. “A Glorified Park” Garden and Forest, July 12, 1893, p. 293–94.

Shepp, James W.; Shepp, Daniel B. Shepp’s World’s Fair Photographed. Globe Bible Publishing, 1893.

Truman, Benjamin Cummings History of the World’s Fair. Mammoth, 1893.

Van Brunt, Henry “Architecture at the World’s Columbian Exposition.—III” Century Aug. 1892, p. 540–48.

Van Rensselaer, Mrs. Schuyler “Let Only Art Reign” Chicago Tribune Sep. 18, 1892, p. 11.

“The World’s Fair Franklin Statue” Scientific American Jan. 23, 1892, p. 55.

“World’s Fair Letter” Wood County (WI) Reporter Mar. 16, 1893, p. 1.

Leave A Comment