[Part 1 of this series (“Chicago Society’s 1894 Charity Bazaar”) describes the organization of a novel society fundraiser called “Echoes of the White City” in Chicago during the fall of 1894, and Part 2 (“A Midway in Miniature”) and Part 3 (“Fourteen Villages and a Jail”) described the attractions and events of the Midway-themed bazaar.]

In 1894, Chicago socialites rebuilt a miniature version of the great Midway Plaisance from the 1893 World’s Fair inside of two downtown armories. For two weeks, guests of “Echoes of the White City—The Midway” patronized some interesting and strange adaptations of the foreign villages and attractions they remembered from the Columbian Exposition, all to raise money for the Chicago Foundling’s Home and the Bethesda Day Nursery and Kindergarten. The bazaar culminated in a “Grand Finale” on November 27.

Forget the hard times and remember only the nation’s playground

Before “Echoes of the White City” opened its doors, managers sent out this announcement: “We no longer hear the dim cry in the distance ‘The camels are coming’; the camels are here, and will bow their lofty heads and bend on callus knee, inviting you to mount.” [“White City Echoes”]

When Opening Night arrived on Tuesday, November 13, Chicago Society came out in force, a throng of enthusiastic spectators—more than 3,000 paying attendees—filled the Battery D and Second Regiment armory buildings on Michigan Avenue. “What the place lacked in the reality,” wrote the Tribune, “was more than made up by the originality displayed in the decorations and the many schemes of entertainment.” [“More of the Midway”]

Presiding over the affair was Matilda B. Carse. She “revived the corpse” of the World’s Columbian Exposition and welcomed patrons with a short opening address. “Out of the past we hear voices,” she told them. “Let us listen and for two weeks forget the hard times and remember only the nation’s playground” that was the 1893 World’s Fair. She asked patrons to “catch the echoes from the far-off White City” and come together for charity.

Thomas W. Palmer, President of the World’s Columbian Exposition National Commission. [Image from Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume I. M. Juul & Co., 1894.]

Harlow N. Higinbotham, President of the Columbian Exposition corporation. [Image from Hitchcock, Ripley The Art of the World Illustrated in the Paintings, Statuary, and Architecture of the World’s Columbian Exposition. D. Appleton, 1895.]

While preliminary press releases noted that George R. Davis, Director-General of the World’s Columbian Exposition and Daniel Burnham, Director of Works, also would speak on Opening Night, no reports confirm that they were in attendance.

After the speeches, the Second Regiment band burst into “Yankee Doodle” and other national airs to begin a “Procession of Nations.” Serenading visitors as they toured each of the concessions were singers from Chicago’s Tabasco Club, a society of young men from the West Side that had formed in 1893.

Precision drills and dress parades by seventy-five men of the First Regiment and 300 men of the Second Regiment entertained visitors in the armory. The Chicago Zouaves, thirty-five strong under the command of Major R. F. Logan, also performed an exhibition drill. The Zouaves performed again on November 16.

Nineteen alumni of the Michigan Military Academy in Orchard Lake, Michigan, formed a special service corps that “camped” near the Moorish Palace and provided nightly drill exercises under Captain Frank Sidley. [One cadet from the Michigan Military Academy cadet in 1894 was Chicago native Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875-1950), who would go on to have an illustrious career as an adventure novelist.]

With opening-night receipts totaling $1000, financial success for the benefit seemed assured.

Special Nights at “Echoes of the White City”

An advertisement for “Chicago Day” at “Echoes of the White City—The Midway.” [Image from the Chicago Daily Tribune, Nov. 18, 1894.]

The “special nights” were:

Scottish Night on Thursday, November 15

Scots who came from around the city for “Scottish Night” were entertained by brilliant Scottish plaid decorations, bagpipers, and a flag drill. An army of the Royal Scots of Illinois paraded in traditional attire and danced the “Highland Fling” with “fifty pretty Scotch lasses not sufficiently Americanized to have lost the roses from their cheeks.” [“Camel Here at Last”] Eight more beautiful women impersonated celebrated characters in Scottish history.

A “Couple of Scotch Lassies” dancing in traditional attire for Scottish Night at the charity bazaar. [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 17, 1894.]

Children’s Night on Friday, November 16

Especially popular among the kiddies who came out for “Children’s Night” were amusements such as the enchanted swing of the Haunted House and the Electric Scenic Theater’s “Illusion of the Flower Girl” (in which a little girl made of stone comes to life); both were described in Part 3 of this article.

Chicago night on Saturday, November 17

Echoing the throngs who packed Jackson Park for Chicago Day at the Fair a year earlier, attendance swelled to double any previous night for “Chicago Night.” A Grand International Parade held at 7:45 pm was repeated on subsequent nights.

An advertisement for “Chicago Day” at “Echoes of the White City—The Midway.” [Image from the Chicago Herald, Nov. 17, 1894.]

Military Night on Monday, November 19

After closing for Sunday, “Echoes of the White City” reopened on Monday evening with “Military Night.” Following the great parade of nations, the rival first and second regiments performed drills.

Suburban night on Tuesday, November 20

“Suburban Night” featured the “Arab Patrol,” a drill performance by twenty-one Masons dressed as a band of Arabs. Tuesday also was celebrated as “Russian Night,” with the local Ozimlijak Russian Club serving tea in Old Vienna—until a band of “Dahomeyans” raided and captured them.

An advertisement promoting “Suburban Day.” [Image from the Chicago Herald, Nov. 20, 1894.]

Actress Kittie Mitchell in 1890. [Image from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.]

Irish Night on Wednesday, November 21

“Wherever a strip of it could be tacked on, there was green bunting, with flags to match,” wrote the Inter Ocean. [“Ireland on the Midway”] Everyone working the bazaar was decked out in green attire—even the “Dahomeyans” wore olive-colored breechcloths, and the Kenwood Minstrels presented “the only living green man” for the occasion.

Adding to the festivity, a champion rope-skipper named John Smith demonstrated his skills by jumping rope 1000 times without stopping. Smith was over sixty years old.

German Night on Thursday, November 22

German Night drew the largest crowd yet—32,000 guests—and Old Vienna was “crowded almost to suffocation.” [“Crowds at the Midway”] There, Dr. Emil Hirsch, rabbi of the Chicago Sinai Congregation, delivered a welcoming address to German guests.

The restaurant sold sauerkraut and wienerwurst while the Second Regiment Band played German music and the Frohsinn Maennerchor choral group sang German songs. Elsewhere, the Ashland and Hungarian orchestras performed.

By Thursday night, organizers were already making plans to extend the show beyond the originally planned closing on Saturday, November 24.

An advertisement promoting “Irish Night,” “German Night,” “College Night,” and “Public School Day” during the second week of the Midway bazaar. [Image from the Chicago Evening Post, Nov. 21, 1894.]

College Boy’s Night on Friday, November 23

Instead of waning, the popularity of the charity event increased during its final days. The “grand charivari and general wind-up” on Friday night became a rowdy “College Boy’s Night.”

Organizers invited President William Rainey Harper of the University of Chicago and President Henry Wade Rogers of Northwestern University to attend. The colors of both schools decorated the Midway booths. Boisterous cheers from the students and alumni of these great institutions—along with their brothers from Lake Forest, Yale, Harvard, Princeton, Cambridge, Cornell, Williams, and dozens of other schools—echoed through the armories.

“The yells which left the throats of the Lake Forest, Northwestern, and University of Chicago boys sounded like thunder in midsummer,” reported the Inter Ocean. [“Will Soon Be Over”] When the three opposing crowds of students would meet at a given point, the cyclonic outburst from their collegiate tonsils dwarfed all the regular barkers.

The Chicago Hussars, an equestrian military group, also performed.

Public Schools Day and Businessmen’s Night on Saturday, November 24.

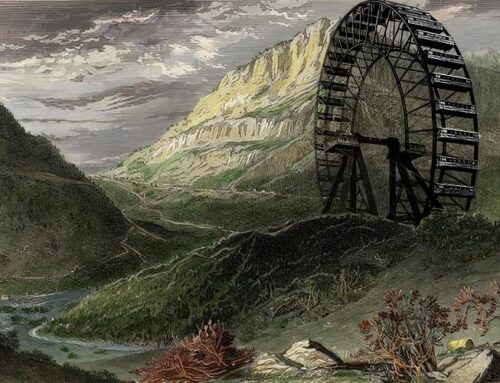

For the “Public School Day” matinee, school children from across the city were admitted at half price and could enjoy a ride on the Ferris Wheel for only five cents. Professor Katzenberger, supervisor of music for the Chicago public schools, brought a choir of 100 children to sing.

“Major Donaldson,” a twenty-six-inch-tall, fourteen-year-old California boy, entertained the children in Old Vienna. The Saturday evening show was a special Businessmen’s Night.

Everybody’s Night or Clergymen’s Night on Monday, November 26

After closing on Sunday, “Echoes” reopened on Monday with “Clergymen’s Night.” Organizers invited Congregational, Baptist, Presbyterian and Methodist ministers to attend the charity bazaar. Members of the Clergymen’s Club and the Blue Monday Club also attended.

The final two days of “Echoes of the White City—The Midway” featured “Everybody’s Night” and a “Grand Finale” night. [Image from the Chicago Daily Tribune, Nov. 26, 1894.]

Grand Finale on Tuesday, November 27

“Echoes of the White City—The Midway” culminated in a “Grand Finale” on November 27, which included the issuing of awards to exhibitors for the previous two weeks.

The Committee on Awards was a veritable who’s who of Chicago and included: Eugene Field (children’s poet and author), Andrew McNally (co-founder of Rand, McNally and Company publishers), William Ellery Hale (president of the Hale Elevator Company), Norman B. Ream (businessman), George A. Fuller (architect), and Mrs. Virginia Claypool Meredith (the “Queen of American Agriculture”) along with several other members of the Board of Lady Managers from the 1893 Fair.

The Committee’s job was an easy one. In order to prevent complications, the members had been instructed privately to bestow the highest award to all contestants. The “award” consisted of a piece of blue paper on which was printed:

HIGHEST AWARD

for

SUPERIORITY AND EXCELLENCE

ECHOES

of

THE WHITE CITY – THE MIDWAY.

Chicago U.S.A.

Nov. 13 to Nov. 27,

1894

JOHN VOID PATCHER,

Chairman Jury of Awards

The award certificate presented to all exhibitors of “Echoes of the White City—The Midway.” [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 28, 1894.]

“Echoes of the White City” Souvenirs

In addition to the blue paper award certificates, a few other souvenirs from “Echoes of the White City—The Midway” were available to hosts and guests.

The Isabella quarter commemorative coin.

Near the Congress of Beauty stood a neatly decorated structure adorned with the Spanish colors and a painting of Queen Isabella. From here, women from the Board of Lady Managers of the Columbian Exposition ran a popular concession booth selling Isabella souvenir coins that remained from the World’s Fair.

Visitors inspired by the “living pictures” display could obtain a “counterfeit presentment” of themselves in the form of a photograph by the Official Photographer of the Midway.

“He Sold Flowers” to raise funds for children’s charities. [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 16, 1894.]

[It would be interesting to know if any of the ephemeral items, such as award certificate and program booklet, survive.]

All that remained was the job of dismantling the Midway once again, getting the beauty-show boys out of their dresses, sending the camels home, clearing out of the armory buildings, and awarding a donated donkey by popular vote.

Who would ride home on the Midway donkey? [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 12, 1894.]

Echoes of the White City will be heard no more

The Tribune described a scene that echoed the melancholy end to the World’s Fair a year earlier:

It is over. The echoes of the White City will be heard no more at Battery D. The Dahomey Villagers have washed the burnt cork off their faces, the Ferris wheel has been taken down, the voice of the eloquent barker at the door of the Electric Scenic Theater is hushed, and the members of the Committee on Awards are in hiding. The camel has gone, the Hagenbeck menagerie of trained animals has dissolved, the Beauty Show has faded, and Old Vienna is an aching void. And the French claims still remain unpaid.” [Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 28, 1894]

The Street in Cairo, “where the camel and donkey are stars,” once again proved to be the most popular exhibit and raised the most money for charity. [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 25, 1894.]

The “brawny beauties” of the Ashland Club pulled in the second-highest ticket sales with their gender-bending Congress of Beauty. The boys gladly returned their sisters’ dresses with hopes that they never again would have to wear them in public.

The next morning, a south-bound passenger train left Chicago carrying a tired camel on his way back to the Cincinnati Zoo. “His part in the show has been a star one, and he earned a large percentage of the receipts,” wrote the Inter Ocean. “Of late the camel has shown considerable temper and was evidently growing morose with being continually sat down upon by Chicago girls, some of whom were far from sylphlike in their style.” [“End of the Midway”]

Closing down the Midway included finding a home for a donated donkey. [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 28, 1894.]

Extremely embarrassing to a donkey of sensitive nature

Another star beast of burden needed to find a home. Toward the conclusion of “Echoes,” Mr. C. H. Fargo, who had loaned one of his donkeys for the Street in Cairo exhibit, donated the “mild-eyed, innocent-looking little beast” to the management of the Midway. They, in turn, decided to use the long-eared heirloom as a prize for either the best newspaper in town or for the most popular preacher to visit the Midway show on Clergymen’s Night. The latter idea won out, and the donkey prize was awarded through a popular vote, at 5 cents a ballot. Recognizing that the “winner” of a donkey would have to buy hay all winter, truly popular clergyman had enough influence over their flock to urge them to withhold votes.

Rev. William T. Meloy, Minister of the First United Presbyterian Church of Chicago, [Image from Memorials of Deceased Companions of the Commandery of the State of Illinois, Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States: From July 1, 1901, to December 31, 1911. 1912.]

“All of this must be extremely embarrassing to a donkey of sensitive nature,” wrote the Inter Ocean, “this thing of feeling that he is a long-eared waif rendered homeless by his misfortune in having been donated to an entertainment for charity and by them voted to a minister who does not want him.” [“Donkey Turns White Elephant”]

The human waifs rendered homeless by misfortune had fared much better from the generosity of Chicago society.

The cast members of “Echoes of the White City” were “All Devoted to Charity.” [Image from the Chicago Herald, Nov. 18, 1894, illustrated by W. W. Denslow.]

The only cause for regret

“Strolling down the original Midway,” observed the Inter Ocean, “one felt a reluctance to think that the large amount of money that was gathered in by the various attractions each day went, for the most part, into hands that would carry it away from Chicago.” [“Fair Ada in Silver”] In contrast, this show benefited Chicago charities.

By the end of the show’s run, 40,000 visitors had brought in $21,963 in gross receipts for a net profit of $10,351. The organizers donated $4,500 each to the Ladies Union Aid Society for their support of the Foundlings Home and to the Chicago Central W.C.T.U. to benefit the Bethesda Day Nursery. These gifts provided for all the expenses of running these two charitable organizations for up to two years.

“The only cause for regret,” admitted manager Cora Scott Pond-Pope, “is that the two halls are not half big enough to accommodate all who would like to attend.” [“Ireland on the Midway”]

In fact—outside of Chicago—other halls were filled with people desiring a chance to see the Midway Plaisance of the 1893 World’s Fair.

[In the Postscript of this series (“One of the Funniest and Best Things of the Kind”) we will travel across the United States to visit other miniature reproductions of the Midway Plaisance.]

SOURCES

“Again the Midway” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 12, 1894, p. 4.

“All Flock to Midway” Chicago Herald Nov. 18, 1894, p. 6.

“Camel Feeling Bad” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 18, 1894, p. 3.

“Camel Here at Last” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 16, 1894, p. 4.

“Campbells in the Midway” Chicago Herald Nov. 15, 1894, p. 7.

Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 28, 1894, p. 6.

“Children’s Day in the New Midway” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 18, 1894, p. 4.

“College Boys’ Yells” advertisement Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 24, 1894, p. 7.

“Crowds at the Midway” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 23, 1894, p. 8.

“Donkey for a Prize” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 25, 1894, p. 9.

“Donkey Turns White Elephant” Chicago Inter Ocean Dec. 2, 1894, p. 8.

“End of the Midway” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 28, 1894, p. 7.

“Fair Ada in Silver” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 17, 1894, p. 6.

“Fun at the Midway” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 15, 1894, p. 5.

“Germans at the Midway” Chicago Evening Post Nov. 22, 1893, p. 10.

“Great Night at Battery Midway” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 26, 1894, p. 3.

“Imitate the Midway” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 11, 1894, p. 7.

“Incidents in Midway Reproduced” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 21, 1894, p. 8.

“Ireland on the Midway” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 22, 1894, p. 8.

“Last Night of the Midway Show” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 27, 1894, p. 2.

“Midway Closes Tonight” Chicago Evening Post Nov. 27, 1893, p. 2.

“Midway Here Again” Chicago Herald Nov. 14, 1894, p. 3.

“Midway is Revived” Chicago Herald Nov. 11, 1894, p. 6.

“Midway Makes a Hit” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 14, 1894, p. 5.

“Military in Midway” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 20, 1894, p. 4.

“More of the Midway” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 14, 1894, p. 8.

“Old Vienna in its Glory” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 23, 1894, p. 3.

“On the Midway Again” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 13, 1894, p. 3.

“Profits of Midway” Chicago Daily Tribune Dec. 21, 1894, p. 6.

“Revived Midway Opens Tonight” Chicago Herald Nov. 13, 1894, p. 7.

“Scottish Night in Midway” Chicago Herald Nov. 16, 1894, p. 11.

“Society” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 20, 1894, p. 8.

“Society” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 21, 1894, p. 8.

“Society” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 23, 1894, p. 8.

“Society” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 24, 1894, p. 6.

“Society” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 28, 1894, p. 5.

“White City Echoes” Chicago Evening Post Nov. 12, 1893, p. 5.

“Will Soon Be Over” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 24, 1894, p. 5.

Leave A Comment