When the Midway reopened in 1894, the Ferris Wheel had only four passenger cars, the girls in the Congress of Beauty had to shave their faces, and the famous “belly dance” was performed by a male window decorator from Marshall Field’s.

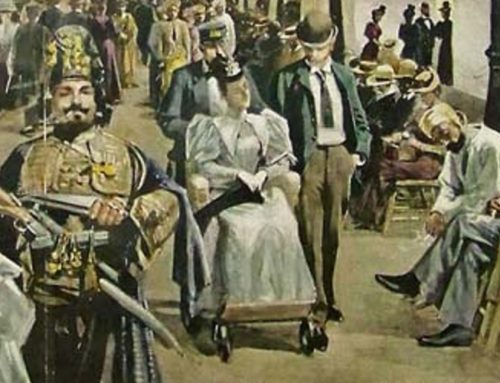

As carriages pulled up along Michigan Avenue, Chicago’s society folk were greeted by a fat, little man wearing “trousers that might have been intended for twin balloons,” a fez, and shoes with turned-up toes. Standing on a red platform, he clapped his hands and shouted “Gooda show, gooda show!” [“Midway Here Again”] As the barker enticed patrons to enter a revived Midway Plaisance erected inside of the downtown armory building, a band in the gallery burst into a rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and a chorus of voices rang out with the tune of “Echoes of the White City—The Midway.”

An advertisement for “Echoes of a White City—The Midway” opening on November 13, 1894, in the Battery D and Second Regiment Armory buildings in Lake Front Park in downtown Chicago. [Image from the Chicago Daily Tribune, Nov. 8, 1894.]

The most important charity entertainment ever given

For two weeks in November of 1894, Chicago society hosted a benefit show with donkey rides, black-face minstrels, living statues, a drag show, a clown-dog circus, and a wrestling show—all to raise money to support abandoned and orphaned children. Inside two downtown armories, the Midway Plaisance rose again with its foreign villages, theatrical shows, thrill rides, shopping, and food. “Echoes of the White City” served as a nostalgic celebration of the city’s successful role as host of the World’s Fair the previous year … and a festival of elitist cultural appropriation.

Extravagant in every detail, the Midway bazaar was “one of the largest and most important charity entertainments ever given” in Chicago. In the days before it opened, the show had created “more of a stir and keener interest than any charity function given since the bazaar at Mrs. Potter Palmer’s” two years earlier. [“White City Echoes”] Arrangement had been made “on a scale that none but Chicago people would think of, and no other would be able to carry through.” [“Midway is Revived”]

The Battery D Armory at Michigan Avenue and Monroe Street in downtown Chicago. [Image from Mack, Edwin F. Old Monroe Street. Notes on the Monroe Street of Early Chicago Days. Central Trust Company of Illinois, 1914.]

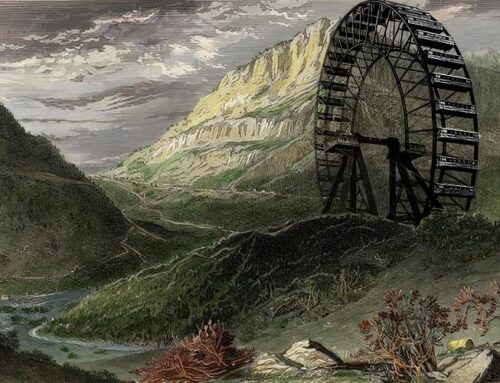

The event ran in the Battery D and Second Regiment Armory buildings on Michigan Avenue, between Monroe and Washington streets. The Battery D Armory, a 140-by-200-foot stone building that could hold 4,000 people, had been erected on the Lake Front in the early 1880s at the north-east corner of Michigan Avenue and Monroe Street (current site of the Crown Fountain in Millennium Park). The building was demolished in 1896 to provide a site for a temporary Post Office. Of similar size, the Second Regiment Armory sat just north, between Madison and Washington streets.

The novel society show served as a benefit for the Chicago Foundling’s Home and the Bethesda Day Nursery and Kindergarten. The Chicago Foundling’s Home was established by Dr. George E. Shipman in 1871, the year of the Great Chicago Fire, to take in unwanted babies; the organization continues to operate today, though with a broader charitable mission. Under the direction of the Central Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, the Bethesda Mission operated the first creché, or day nursery, in Chicago and was founded by Matilda B. Carse.

Matilda B. Carse. [Image from Willard, Frances Elizabeth; Livermore; Mary Ashton Rice A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life. Charles Wells Moulton, 1893.]

Women ran “Echoes of the White City.” Coming up with the idea for the fundraiser was Matilda Bradley Carse (1835-1917), who served as its Chair of the Committee of the Joint Charities. With Frances E. Willard and Lady Henry Somerset, Carse helped found the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), and she had served as a member of the Board of Lady Managers and the founder and president of the Woman’s Dormitory Association of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Assisting Mrs. Carse were Mrs. L. M. Crum (Krum) as secretary; Mrs. Lyman J. Gage (wife of the first president of the Columbian Exposition) as treasurer; and Mrs. Thomas Kane, Mrs. L. A. Small, Mrs. Fred L. Fake, Mrs. E. P. Howell, and Mrs. Robert L. Greenlee as directors.

Cora Scott Pond-Pope. [Image from Willard, Frances Elizabeth; Livermore; Mary Ashton Rice A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life. Charles Wells Moulton, 1893.]

Mrs. Cora Scott Pond-Pope (1856-1932) served as manager of the fundraising bazaar. Pond-Pope was described as having “much experience” in managing events such as this … though, there never was any event such as this in Chicago! [“Pope, Mrs. Cora Scott Pond”] An activist for women’s suffrage, Pond-Pope had organized a week-long bazaar in 1887 at Music Hall in Boston. She then traveled the country, giving “National Pageant” fundraising concerts. One, held at the Auditorium Theater in Chicago c. 1891, raised $60,000 on a single night. A modern biographer describes Pond-Pope as “a militant prohibitionist (she declined fermented communion wine) and real-estate investor who refused to wear a corset starting at the age of 16.” In the early twentieth century, Pond-Pope became a real estate investor in Los Angeles, and her legacy is remembered in the Highland Park neighborhood.

The original Midway Plaisance, as shown in the watercolor “Along the Plaisance” by Charles Graham. [Image from Graham, Charles S. The World’s Fair in Water Colors. Mast, Crowell & Kirkpatrick, 1893.]Rich in color and ornate in design

“Society is absolutely devoted to charity these days,” observed the Chicago Herald. [“Devoted to Charity”] In the year since the World’s Fair closed its doors and in the midst of an economic depression, prominent Chicagoans found themselves caught in a fashionable whirl of benevolent balls and benefit bazaars. Nothing, however, matched the splendor and excitement of the resurrected Midway Plaisance.

An advertisement for “Echoes of the White City” promises “800 Society People.” [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 11, 1894, p. 16.]

Advertisements promised “800 Society People representing Turks, Chinese, Egyptians, Japanese, Bedouins, Soudanese, Javanese, Laplanders, Arabs, Dahomeyans, Hindoos, Columbian Guards …” One thousand of Chicago’s fairest daughters–young ladies belonging to prominent social circles–would dress in exquisite costumes of the countries and peoples they depicted. The masquerade would offer guests “a kaleidoscope of Oriental costumes, rich in color and ornate in design, worn by pretty American maids whose Caucasian complexions added to the charm of the characters and nationalities they assumed.” [“More of the Midway”] No one in 1893 Chicago society found this the least bit racist.

The original Midway Plaisance also was a problematic delight. Concessionaires, not government sponsors, operated most of the foreign villages as private companies through contracts with the Exposition corporation. The international cultures showcased on the Midway were in the business to entertain visitors and sell tickets and goods from the attractions. Authenticity was secondary to amusement.

An advertisement promises “Magnificent Scenery, Beautiful Costumes, Fine Electrical Effects” for the recreation of the Midway. Chicago society people dressed up as Arabs, Native Americans, and Sámi (Laplanders) for the bazaar. [Image from the Chicago Herald Nov. 13, 1894.]

The 1894 Midway recreated by and for Chicago’s elite was whitewashed with a fresh coat of staff. As society folk donned the costumes of their former international guests, their bazaar would be a cleaned-up and proper social event. The press noted that “every feature of the old Midway Plaisance, except the Turkish dances, is to be reproduced as nearly as possible.” [“‘The Midway’ for Charity”] There would be no hoochie-coochie dancing at this event. Or would there?

Scenes of rare beauty and extraordinary taste

Thomas Gibbs Moses, scenic artist who prepared backdrop paintings of the Midway for “Echoes of the White City.”

Elaborate decorations transformed the armory spaces into “scenes of rare beauty and extraordinary taste and intelligence.” [“Midway Here Again”] Supervising the design and scenic effects was Thomas Gibbs Moses (1856-1934) of the Schiller Theater in Chicago. Described as “one of the most noted scenic artists of the city,” [“Midway is Revived”] Moses had begun working on paintings for “Echoes” in early October. He created a backdrop for the western (Michigan Avenue) entrance to Battery D depicting the arcade under the railroad across the Midway, while another backdrop between the Turkish and Chinese Theatres represented the entrance to the Street in Cairo compound. Moses went on to become a nationally known scenic designer with Broadway credits.

Richard H. Pierce, electrical engineer for the 1893 World’s Fair, wired the new Midway for “Echoes of the White City” in 1894. [Image from “R. H. Pierce, Electrical Engineer at the World’s Fair.” Western Electrician Mar. 18, 1893, p. 138.]

Electrical effects for “Echoes of the White City” were created by Richard H. Pierce, the chief electrical engineer of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition who had designed the installation and wiring and lighting for the buildings and grounds in Jackson Park.

Rebuilding the Midway for “Echoes of the White City.” [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean, Nov. 13, 1894.]

All that it pretends to be

After weeks of work and $2000 spent on constructing the scenery and booths, nearly twenty reproductions of original Midway attractions began to fill the armory buildings. The picturesqueness, oddity, and cleverness of the bazaar promised to surpass any similar endeavor in the city. Visitors who had experienced the Midway at the 1893 World’s Fair would be “vastly amused at the clever imitations.” [“On the Midway Plaisance”] The Chicago Inter Ocean wryly observed that the new Midway “is not fake … it is all that it pretends to be.” [“Opening of the Midway”]

After a dress rehearsal on Saturday, November 10, at the Sherman House Hotel (located on the northwest corner of Clark & Randolph streets in the Chicago Loop), “Echoes of a White City—The Midway” opened at the armory buildings on the evening of Tuesday, November 13. The benefit ran for two weeks, open each evening from 7 pm to 11 pm and with Saturday matinees at 2 pm.

[Part 2 of this article (“A Midway in Miniature”) will describe some of the attractions and events of “Echoes of a White City.”]

SOURCES

“Devoted to Charity” Chicago Herald Nov. 18, 1894, p. 38.

Johnson, Rossiter History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Held in Chicago in 1893, Volume 1: Narrative. Appleton, 1897.

Mack, Edwin F. Old Monroe Street. Notes on the Monroe Street of Early Chicago Days. Central Trust Company of Illinois, 1914.

“‘The Midway’ for Charity” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 2, 1894, p. 8.

“Midway Here Again” Chicago Herald Nov. 14, 1894, p. 3.

“Midway is Revived” Chicago Herald Nov. 11, 1894, p. 6.

“More of the Midway” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 14, 1894, p. 8.

“On the Midway Again” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 13, 1894, p. 3.

“Old Buildings to Go” Chicago Daily Tribune May 21, 1895, p. 8.

“On the Midway Plaisance” Chicago Evening Post Nov. 14, 1893, p. 2.

“Opening of the Midway” Chicago Inter Ocean Nov. 13, 1894, p. 8.

“Pope, Mrs. Cora Scott Pond” in Woman of the Century by Frances E. Willard and Mary A. Livermore, Charles Wells Moulton, 1893, p. 581.

“Profits of the Midway” Chicago Daily Tribune Dec. 21, 1894, p. 6.

“Revived Midway Opens Tonight” Chicago Herald Nov. 13, 1894, p. 7.

“R. H. Pierce, Electrical Engineer at the World’s Fair.” Western Electrician Mar. 18, 1893, p. 138.

“Society” Chicago Daily Tribune Nov. 8, 1894, p. 13.

“White City Echoes” Chicago Evening Post Nov. 12, 1893, p. 5.

Leave A Comment