[Previous installments of this series include Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.]

This fifth part of Harriet Monroe’s “The World’s Columbian Exposition” from John Wellborn Root: A Study of His Life and Work (Houghton, Mifflin & Company, 1896) describes how John Root in late 1890 assembled the “best fruit” of American architecture to design the buildings of the 1893 World’s Fair.

Part 5: Expect to be Judged by the World

Root looked upon the Columbian Exposition as a great opportunity for his profession, and he accepted the post of consulting architect with the avowed purpose of concentrating upon this work the best American talent, and of making it an object-lesson to the people in the management of great building enterprises. His appointment gave him wide discretion. Though the Grounds and Buildings Committee intended to invite the collaboration of other architects, it did not assume the initiative in this matter, but permitted Root to formulate his own scheme for an architectural corps. It was taken for granted, meanwhile, by the majority of directors, by the press and the public, that he would be the designer of the principal buildings. His professional confrères expected this also; Eastern architects had no hope of participating in the work, and those in Chicago were bitterly suspicious of exclusion. I remember how Root came home one evening, soon after his appointment, cut to the quick because one of these, always hitherto a friend, had apparently refused to recognize Mr. Burnham when they met at a club. “I suppose he thinks we are going to hog it all!” he exclaimed, disheartened.

Soon, against all persuasion, he announced his intention of designing none of the chief buildings in Jackson Park. To preserve the impartiality of a judge would be impossible, he insisted, if he should assume a rôle. Both he and Mr. Burnham wished to give the great enterprise a national character by inviting the leading architects in the country to take part in it, and to this end they now directed their energies before the Committee on Grounds and Buildings. December 8 Root presented a memorial to this committee, describing impartially four possible methods of procedure. It reads as follows in the original manuscript in his hand writing:—

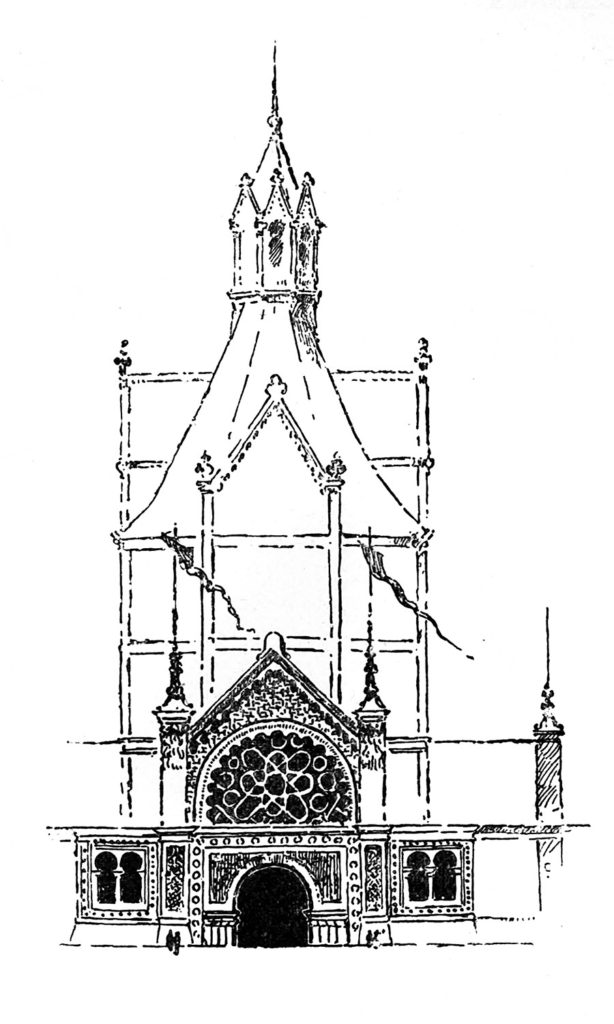

Root’s study for exposition buildings in Jackson Park.

“Preliminary work in locating buildings, in determining their general areas, and in other elementary directions necessary to proper progress in the design and erection of the structures of the Columbian Exposition has now reached a point where it becomes necessary to determine the method by which designs for these buildings shall be obtained. We recognize that your action in this matter will be of great importance not only in its direct effect upon the artistic and commercial successes of the Exposition, but, scarcely less, upon the aspect presented by America to the world, and also as a precedent for future procedure in this country by the government, by corporations and individuals.

“In our advisory capacity we wish to recommend such action to you as will be productive of the best results, and will at the same time be in accord with the expressed sentiments of the architectural societies of America. Whatever suggestions are here made relate to the main buildings located in Jackson Park. That these buildings should, in their designs, relationship, and arrangement, be of the highest possible architectural merit is of importance scarcely less than the variety, richness, and comprehensiveness of the various displays within them. Such success is not so much dependent upon the expenditure of money as upon the expenditure of thought, knowledge, and enthusiasm by men known to be in every way endowed with these qualities. And the results achieved by them will be the measure by which America, and especially Chicago, must expect to be judged by the world.

“Several methods of procedure suggest themselves: —

“1st. The selection of one man to whom the designing of the entire work should be entrusted.

“2d. Competition made free to the whole architectural profession.

“3d. Competition among a selected few.

“4th. Direct selection.

“1st. The first method would possess some advantages in the coherent and logical result which would be attained. But the objections are, that time for preparation of designs is so short that no one man could hope to do the subject justice even were he broad enough to avoid, in work of such varied and colossal character, monotonous repetition of ideas.

“2d. The second method named has been employed in France and other European countries with success, and it would probably result in the production of a certain number of plans possessing more or less merit and novelty.

“But in such a competition much time, even now most valuable, would be wasted, and the result would be a mass of irrelevant and almost irreconcilable material which would demand great and extended labor to bring into coherence. It is greatly to be feared that from such a heterogeneous competition the best men of the profession would refrain, not only because the uncertainties involved in it are too great, and their time too valuable, but because the societies to which they almost universally belong have so strongly pronounced its futility.

“3d. A limited and paid competition would present fewer embarrassments; but even in this case the question of time is presented, and it is most unlikely that any result derived through this means, coming, as it would, from necessarily partial acquaintance with the subject and hasty, ill-considered presentation of it, could be satisfactory.

“Far better than any of these methods seems to be the last.

“4th. This is to select a certain number of architects because of their eminence in the profession, choosing each man for such work as would be most parallel with his best achievements; these architects to meet in conference, become masters of all the elements of the problems to be solved, and agree upon some general scheme of procedure ; the preliminary studies resulting from this to be freely discussed in a subsequent conference, and, with the assistance of such suggestions as your advisers might make, to be brought into a harmonious whole.

“The precise relationship between the directory and these architects might safely be left to a general conference, at which all questions of detail could be agreed upon. The honor conferred upon any man thus selected would create in his mind a disposition to place the artistic quality of his work in advance of the mere question of emolument; while the emulation begotten in a rivalry so dignified and friendly could not fail to be productive of a result which would stand before the world as the best fruit of American civilization.”

This memorial was emphasized by oral argument, and its recommendations were adopted by the Grounds and Buildings Committee. Burnham and Root had determined, weeks before, upon their board of architects, and now live representative firms from other States were nominated, confirmed, and notified of their appointment, viz.: Richard M. Hunt, McKim, Mead & White, and George B. Post, of New York; Peabody & Stearns, of Boston; and Van Brunt & Howe, of Kansas City. It was intended that these gentlemen should design the main group of buildings around the Court of Honor, leaving the other buildings for Chicago architects. But they were no sooner appointed than strong opposition to the employment of outsiders began to impede the action of the committee. It was said that Chicago was paying for the Fair, and Chicago men should have the designing of it; and that, moreover, professional talent in this city, compared with that in the East, was fully as competent and more progressive. Under pressure from local architects and their friends in the directory, and from the spirit of local patriotism in general, there was danger, in spite of the firmness of certain members of the committee, that the appointment of the five firms might be rescinded. Both the consulting architect and his partner, who, late in October, had been appointed chief of the newly organized Department of Construction, thus becoming the executive captain of the great enterprise, were forced to fight many wordy battles, both in and out of committee rooms, to sustain the national character of the exposition. On Saturday, December 27, Root was before the Grounds and Buildings Committee to present, on the part of the Construction Department, a report stating, among other matters, that the Eastern architects would accept their appointments. At this meeting, with his usual quiet marshaling of facts and arguments, he persuasively defended the appointment of these men on broad grounds of public policy, and urged the committee to hold its ground. On December 30, members of the committee spoke strongly in the same vein, holding that they were in honor bound to stand by their action; and the matter was so decided on January 5.

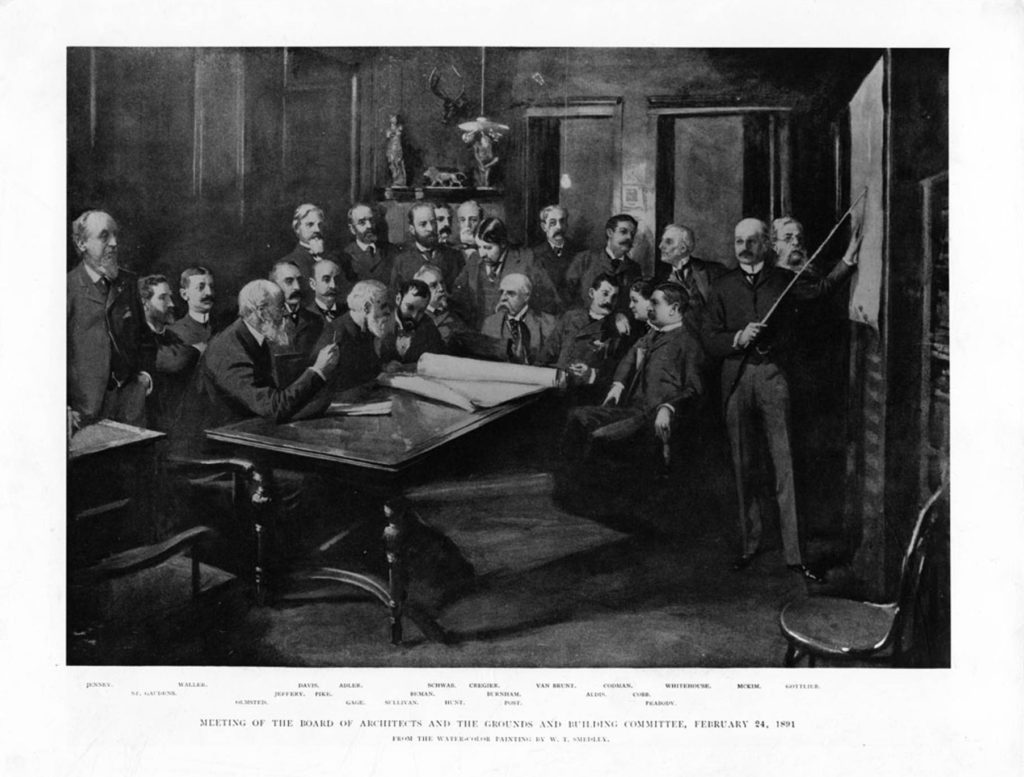

Meeting of the Board of Architects and the Grounds and Building Committee, February 24, 1891. (from The Book of the Builders.)

In the report presented by Root on December 27, the committee was requested, “as the above reported action covers all that may be expected by this committee as to its outside designers,” to confirm the nomination of ten specified Chicago firms for the designing of other structures. On January 5 the committee divided the list of ten by two, authorized Mr. Burnham to notify the five firms, fixed January 10, 1891, as the date of the first Conference of the Board of Architects, and gave to the Chief of Construction absolute freedom in the assignment of work to the various designers. The committee never passed upon any design after its acceptance of the ground-plan, wisely leaving all questions of art to the artists.

Thus the great work of designing and constructing the Columbian Exposition began in a spirit of friendliness and high emulation. The magnanimity of Burnham and Root, the largeness of their point of view, could not but conciliate their rivals and extinguish jealousy. So it was with universal approbation that the Grounds and Buildings Committee, in conjunction with the Art Institute, requested this firm to present designs for the Fine Arts Building, which was then assigned to the Lake Front, and which was to become after the Fair the city’s permanent Museum of Fine Arts. This commission Root accepted as a great opportunity, and it was his favorite study during the last months of his last year. Too long had his muse been claimed by commerce; now at last she was winning for the poet-architect tasks after his own heart. These Columbian honors promised to open a new era in his art, and his spirit responded gladly to the inspiration. Dimly the people for whom he wrought were beginning to recognize in this man a leader; one aware of beauty, persuasive to make them long for it, strong to make it real for them. Though scarcely conscious of their allegiance, they were yet bearing him on their shoulders during these weeks of heroic exertion, and he felt behind his creative force that mighty force of public sympathy which alone can nerve great souls to put forth their utmost power.

Leave A Comment