“The World’s Columbian Exposition has never been so well revealed and appreciated as through her imagination and her eyes,” wrote renowned poet William Carlos Williams, describing fellow poet and publisher Harriet Monroe (1860–1936). “And her part in it was distinguished.”

Two of Monroe’s distinguished accomplishments served as bookends to the 1893 World’s Fair. The Dedication Day Ceremony held on the fairgrounds on October 21, 1892, featured a reading of an excerpt of her monumental poem “The Columbian Ode.” Harriet Monroe’s 1896 biography of architect John Root, her brother-in-law, provided an in-depth account of the early days of planning and designing of the World’s Fair in Chicago. Her account of the Columbian Exposition ends with Root’s sudden death on January 15, 1891.

We reprint here in five parts, Harriet Monroe’s “The World’s Columbian Exposition” from John Wellborn Root: A Study of His Life and Work (Houghton, Mifflin & Company, 1896).

Part 1: We Should Have a Great American Fair

Late in the eighties the militant young metropolis became possessed of a new ambition. The French exposition came and passed, the four hundredth anniversary of the landing of Columbus drew near, and projects for the commemoration of the great discovery crystallized into a demand upon the United States government for an international exposition. In the contest which followed between the different cities, Chicago had from the beginning the advantage of faith. It was no idle faith, however; not that easy sense of security by which New York lost the honor. The enthusiasm of the city was set on its mettle; an aggressive campaign was organized, and five million dollars pledged by private subscription, before other cities had begun to act. In the winter of 1889-90 Chicago sent to Washington a committee of her foremost citizens, fully equipped with large promises, and prepared to assure Congress that the great prize, once in their hands, would not “get into politics.” New York could not offer such assurances, neither was she so richly provided with available sites. Other cities contesting were manifestly unfit. Thus on the twenty-fourth of February, 1890, the House of Representatives passed the bill locating the Columbian Exposition at Chicago, fixing the four-hundredth anniversary in October, 1892, for the dedication of buildings, and May to November, 1893, for the six months’ festival. This bill soon passed the Senate, and became a law in April by the signature of the President.

No true Chicagoan ever doubted the ability of his city to win the prize and to wear it with honor. While Eastern newspapers were predicting “a cattle-show on the shore of Lake Michigan,” Chicago business men brought all their executive experience to this novel enterprise, organized its great stock-company, appointed capable directors and officers, who in turn allotted the numerous committees and commenced the work. One of the surprises of the fair was the success of these business men in their new roles. Bankers and merchants were appointed to committees on grounds and buildings, music, ceremonies, were called upon to decide delicate questions of taste and diplomacy, and as a rule proved intelligently equal to the new demands. From the first their fellow-citizens trusted them; perceived that they appreciated the magnitude of their task. Even men who, like John Root, were possessed by visions of beauty, doubted little that the opportunity would be given for fulfilling them.

From the moment Congress awarded the prize, Root took high ground in regard to the fair. At that time few hoped to rival Paris; the artistic capacity and experience of the French made us distrustful of ourselves. We should have a great American fair, but in points of grouping and design we must expect inferiority to French taste. To such doubts Root opposed his ardent energy. “We have more space, more money,” he would say; “and we have the lake; why should we not surpass Paris?” He had not seen the Exposition Universelle, but he absorbed it now through figures and photographs. The minutest details of design, arrangement, and dimensions were ready for reference in his serviceable memory, and his faculty of architectural clairvoyance made the French exposition a reality to his vision, so that he astonished persons who were familiar with it by the accuracy and completeness of his superior knowledge. His first idea was to place the Chicago fair on the Lake Front—the strip of public land east of Michigan Avenue and between Lake and Twelfth Streets. The Illinois Central tracks were to be depressed and covered, and a wide area of land eastward reclaimed from the lake, inside the government breakwater, by filling for the grounds and piling under buildings. Root saw here an opportunity for a lasting public improvement in the heart of the city, which should make a beautiful park, adorned with an art museum, a music hall, and perhaps one or two other permanent buildings, out of a worn and unsightly strip of sward and a few hundred feet of the lake—a project which, though not carried out for the Fair, is now (1896) being promoted, with good prospect of success, by leading citizens for the advantage and beauty of the town. The Lake Front location had other advantages, notably that of accessibility, which caused it to be favored at first by the directors. At the first meeting of the Grounds and Buildings Committee, May 9, 1890, the Lake Front was chosen as the site for the Fair, and a committee of three appointed to investigate the legal difficulties which lay in the way of securing it. Doubts soon began to assail the committee, however, for on May 15 we find it advertising for proposals of an available site, embracing at least 250 acres unbroken. (The area finally covered embraced 686 acres, of which 189 were under roof.) During the following three months many sites were proposed and discussed. Jackson Park, then a forlorn waste of sand and bogs just redeemed from long litigation, was offered by the South Park Commissioners. The entire West Side park system—three improved parks connected by boulevards—was tendered from the west. A “northwest site” near the north branch of the Chicago River, and a “north-shore site”—wooded lands on the lake shore near Buena Park—were offered by private capitalists. Each of these sites was strenuously urged upon the committee, whose gloom deepened as the tangle became more complicated. On August 10th Mr. Frederick Law Olmsted, the distinguished landscape, architect, came to Chicago at the invitation of the committee. Burnham and Root offered him the hospitality of their large offices, and he states that from this time he and Root, renewing an old acquaintance, were continually in conference.

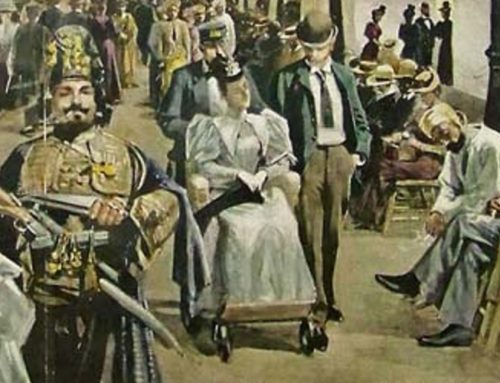

An 1890 Rand McNally map of Chicago, showing the site of the Columbian Exposition in Lake Front Park on the downtown lake shore.

Mr. Olmsted’s first reports were not auspicious for Jackson Park. He doubted if enough land could be reclaimed from the morass, and preferred the north-shore site, which was high and well wooded, in case railroad communication could be secured. This expert opinion only increased the uncertainty, and the contest waxed warm during these August days. The heat of it absorbs me even now, as I glance over a book of newspaper clippings, with their contradictory head-lines.

Aug. 12. “Fair may all go to Lake Front.”

Aug. 13. “Can Midway be secured?”

Aug. 14. “Site in a tangle; directors in deep gloom.”

Aug. 15. “Lake Front is lost; not to be reconsidered.”

Aug. 18. “Practically settled for Jackson Park alone.”

Aug. 20. “North shore in favor.”

And thus for weeks opinion veered back and forth before a committee anxious for the best results, but uncertain where to find them. On August 20 this Grounds and Buildings Committee appointed Messrs. F. L. Olmsted and Co. consulting landscape architects. “There is no more eminent artist living than Mr. Olmsted,” said Root to some of the directors. “His appointment means much for the Fair—is an omen of highest promise. He is a genius.” The next day John Root was made consulting architect, an appointment amended on September 4, at Root’s request, so as to include his partner. On that day, having recently returned to town from the seashore, he had a two hours’ session with the committee, explaining his ideas for the great show, so far as they had taken form.

Leave A Comment