The new musical biopic The Greatest Showman starring Hugh Jackman is shining the spotlight on the life and time of Phineas Taylor Barnum. Although the legendary circus showman died before the Columbian Exposition opened in Chicago in May of 1893, Barnum penned some thoughts on the upcoming World’s Fair–then slated for 1892 in a still undetermined city. His short piece was published in March 1890 issue of The North American Review. Perhaps the greatest showman on Earth would have enjoyed the “stupendousness of the incongruity” found between the White City and the Midway.

WHAT THE FAIR SHOULD BE

by P. T. Barnum

P. T. Barnum (1810–1891)

I do not consider myself especially competent to discuss the question of a world’s fair, particularly in a technical way. I have only seen one great international exhibition, that at Philadelphia in 1876, and therefore I can say little in response to your questions as to the general plan of the fair, wherein it should differ from its predecessors, and what are the pitfalls its managers should guard against. To the first question I might respond generally, Make it bigger and better than any that have preceded it. Make it the Greatest Show on Earth, –greater than my own Great Moral Show–if you can. It should differ from its predecessors in having twice as many visitors, with a hundred times better accommodations for them. It might differ from the Paris exhibition in particular in being located in a city where living accommodations are not raised to extortionate prices merely because that city has its visitors in its power. Nothing is calculated to send the average traveller back to his native country in higher dudgeon than to find that the foreigners upon whose hospitality he has been thrown have fleeced him. I know, of my own knowledge, of hundreds of Americans who attended the Paris exhibition last summer and found the hotel rates higher than the Eiffel Tower, and to whom their expense accounts seemed bigger than the exposition grounds. The chances are that those people will remember the extortion they suffered longer than the great monuments of human industry and progress they witnessed.

The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, built to house the Great Exhibition of 1851.

Of the great moral and educational influence exerted by international exhibitions there can be no two opinions among intelligent men. The first world’s fair, at the Crystal Palace in London, in 1850 [sic], was the greatest civilizer ever known. Many believed at that time, with the Prince Consort, who organized the fair, that, after all the great nations of the earth had been thus brought together in social and industrial convention, wars among men would cease. And so they would, perhaps, if all rulers had possessed the humane disposition and philosophical mind of Prince Albert. To him it seemed impossible, after all the countries had brought their products and manufactures together, and thus discovered how common were their interests, and how surely international harmony would foster trade and advance the conditions of their peoples, that they should again fall out and slaughter each other upon trivial issues and political technicalities.

But though there have been several great wars since the various nations removed their exhibits from the Crystal Palace, that first exposition exercised a great beneficial influence upon humanity, and particularly upon the masses of the people. Before that time, of course, the great men of the different countries, the rulers, nobles, and ambassadors, had met and realized that all men belonged to one great human family. The few men who at that time had travelled in other countries knew this as well. With other orders of society in all countries it was different. The average Englishman, Frenchman, or German, for instance, considered the Turk a wild beast rather than a human being, and believed that all Americans spat tobacco juice in drawing-rooms and carried bowie knives. The masses of the Europeans knew their nearest neighbors best as enemies upon the battlefields, and thought of them as the murderers of husbands, brothers, and sons.

When, however, the merchants and traders of all countries met on common ground in England, animated by a common purpose, there was a tremendous change in popular feeling. The Englishman, for example, found the Turkish merchant polite and urbane, with his thoughts as far away from general murder as the Englishman’s own. The polished Frenchman found the despised Chinaman as dignified and as courteous as himself. The German traders and farmers were surprised to learn that America and Russia possessed farming implements and had made inventions exceeding in many instances their own. The influence exerted by the dissemination of so much practical information when the visitors returned to their homes had a wonderfully broadening effect upon the popular mind. Each succeeding international exhibition has increased knowledge and pacific feeling, and these will be still further enhanced when the greatest country in the world opens her gates, on a great anniversary, to the industrial and commercial elements of the two hemispheres.

There is only one place in the United States to hold the world’s fair, and that is New York city. No one appreciates or admires the enterprise and energy of our great Western cities more than I do, but I am sure their populations will consent to put aside selfish considerations in order to make the exhibition of ’92 a credit to our republic in the highest degree. To expect every visitor to America to travel half way across the continent, after making the ocean journey, would have the same effect upon prospective visitors as the thought to an American of a journey to St. Petersburg instead of London. Aside from that, New York is our metropolis, and the foremost city of America in the best American sense. Again, in considering the financial success of the fair, we depend upon American visitors, upon the people who visit it, not once, but half a dozen or a score of times, and pay their admission each time. New York is virtually our centre of population. It is of easy access to the people of Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, Pittsburg, Baltimore, Bridgeport, and all the great cities of the East, whose combined population is probably twenty or one hundred times that in a similar radius around of any other city that has been mentioned for the exposition. The fair must not be off the island, however. The best site for it, in my judgment, is the one selected by the committee at the north end of Central Park.

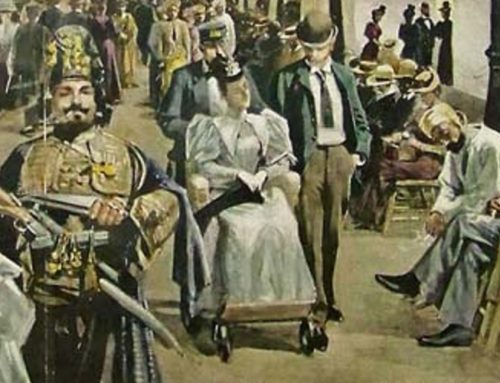

The Egyptian Temple of Luksor on the Midway Plaisance realized an idea proposed by P. T. Barnum three years earlier.

What novel feature would I propose? Now, I will present the Fair Committee with one of my ideas–an idea that might bring me in a million of money. In the museum at Boolak, in Egypt, lies the mummy fled corpse of Rameses II, the Pharaoh of the Exodus, with that of his daughter, the saviour of Moses, and other less distinguished of the royal Egyptian family of that era. I had authorized an agent to offer the Egyptian Government as much as $100,000 to allow me to exhibit those remains in Europe and the United States. I will relinguish [sic] my right of priority of claim in the idea to the Fair Committee. Let them obtain the loan of these mortuary relics from the Egyptian Government, and allow the Khedive to send his own soldiers to guard the coffins. Think of the stupendousness of the incongruity! To exhibit to the people of the nineteenth century, in a country not discovered until 2,000 or 3,000 years after his death, the corpse of the king of whom we have the earliest record! Consider, too, that that corpse is so perfectly preserved after thousands of years in the tomb that its features are almost perfect; so perfect that every man, woman, and child who looks upon the mummy may know the countenance of the despot who exerted so great an influence upon the history of the world. And it might be a useful thought to this generation, proud of its scientific and mechanical triumphs, to bear in mind that the art that embalmed the body of Rameses so perfectly is lost, with a great many others that were known to remote antiquity.

Leave A Comment