SUMMARY: The lion sculptures by Edward Kemeys that stand in front of the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) are not cast from sculptures at the 1893 World’s Fair. This misinformation, which appears to have originated in the late 1980s, now permeates descriptions of these iconic Chicago mascots in institutional, popular, and scholarly sources. Eight pairs of lion sculptures stood at the entrances to the Palace of Fine Arts at the World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE), and numerous contemporary sources credit their authorship to A. Phimister Proctor and Theodore Baur (not Kemeys). More importantly, the designs of Kemeys’ AIC lions clearly do not match any of the WCE lions.

FIGURE 1: The lion just south of the entrance to the Art Institute of Chicago “stands in an attitude of defiance.” The origin story behind this sculpture stands in an attitude of mystery.

Introduction: Mascot Mysteries

Along with the six-pointed star and “the Bean,” they may be the most recognized icons of Chicago. Since 1894 these unofficial mascots have stood guard in front of the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC). They’ve flaunted festive wreaths during the winter holiday season, sported headgear when Chicago’s professional athletic teams reach their play-offs, and even worn masks at the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Although Chicago’s famous lions have no official names, sculptor Edward Kemeys described the north lion as “on the prowl” while the south lion “stands in an attitude of defiance.” These monikers could well describe the myths and mysteries surrounding their origins, specifically an oft-asserted connection to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE). The hunt for information about Chicago’s pride of lion sculptures from 1893 offers a quarry of evidence refuting such a connection.

Part 1 of this article explores the various lion sculptures made for the 1893 World’s Fair and attempts to establish authorship of the two pairs produced for the Palace of Fine Arts building. Part 2 focuses on Edward Kemeys’ 1893 commission to prepare a (different) pair of lions for the Art Institute of Chicago.

FIGURE 2: “On the Prowl” on the move. On Tuesday, June 14, 2022, the lion sculptures in front of the Art Institute of Chicago were removed for some much-needed cleaning and preservation work. A short video of the move is posted on our YouTube channel.

Part 1: Lions of the Fair

“By the bye, it seems to me little less than deliberate cruelty on the part of the Art Directory to place side by side with these masterpieces by Kemeys the amorphous and anomalous concoctions of the unfortunate young man who got the commission for the polar bear, the elk, and the jaguar.”

—from “The Lady of the Lake” by Julian Hawthorne, comparing the artwork of Edward Kemeys and A. Phimister Proctor

Origin stories

The story that the pair of Art Institute lions are bronze castings of plaster statues from the Palace of Fine Arts at the 1893 World’s Fair is so entrenched in Chicago lore that it stands in defiance of the paucity of evidence supporting it. First, the claims.

Civic institutions such as the Chicago Park District and the Grant Park Conservancy offer the conventional origin story:

“The World’s Columbian Exposition in Jackson Park showcased twelve of [Kemeys’] sculptures including massive jaguars, bears, bison, and temporary versions of these lions. Like most of the other exposition artworks, the Lions were originally composed of plaster. During the fair, they flanked the primary entrance to the Fine Arts Palace … Shortly after the fair closed, Mrs. Henry Field donated funds to recast the Lions in bronze and install them in front of the Art Institute’s new building in Grant Park.”

The Museum of Science and Industry (MSI), which now occupies the reconstructed Palace of Fine Arts building in Jackson Park, also has attributed the sculptures that once stood in front of it to Edward Kemeys, reporting that “the two lions that flanked the building’s south entrance during the Columbian Exposition were recast in bronze after the fair and relocated to the entrance of the new Art Institute building on Michigan Avenue.” The 1994 MSI report makes matters worse (and contradicts itself) several pages later, stating that “the two lions that flanked [the south] entrance were moved, after the fair, to the Art Institute’s main entrance.” [“Museum of Science and Industry” 2, 16] The Smithsonian American Art Museum implies the same connection, stating: “In 1893, Edward Kemeys sculpted several pieces for the World’s Columbian Exposition, including the two lions that flank the entrance to the Art Institute of Chicago.”

Many popular histories of Chicago and its artwork amplify this account. One earlier history contains several errors, claiming that Edward Kemeys designed his AIC lions, as well as bison and elk, for the bridges of the 1893 World’s Fair; the elk sculptures were authored by a different sculptor (see below). [Hansen 219] “Like so many things in Chicago, the history of the lions can be traced back to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition,” explains Chicago’s favorite tour guide, Geoffrey Baer. [“Ask Geoffrey”] Echoing this narrative are Donald Krehl’s Monumental Chicago (2011) and Statue Stories Chicago, which records that “plaster versions of the lions stood near the Fine Art Palace at Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. They were recast in bronze and installed in front of the Art Institute when it opened to the public the following year.”

A notable exception is AIC Associate Director of Communications Paul Jones’ 2018 short history “The Lions of Michigan Avenue,” which carefully avoids repeating the claim of the lions having a direct link to the Fair. Another is Dennis H. Cremin, who states that Kemeys “drew inspiration from the lions” at the Fair. [Cremin 82]

Local news outlets regularly repeat the claim. During conservation work in 2022, the Chicago Sun-Times wrote that “the lions were created for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition by sculptor Edward Kemeys” and that the pieces were “moved to the Art Institute” after the Fair. [“Art Institute Lions”]. The Chicago Tribune indicated the same. [“Art Institute Lions Head for a Steam and Wax …”]

At the time of the AIC lions’ centennial in 1994, the story was floating around the Windy City. “In 1893 sculptor Edward Kemeys made plaster lion models for the World’s Columbian Exposition. The 10-feet-long lions were just two of Kemeys’ many creature creations roaming the fairgrounds,” reported the Chicago Tribune. “At the time, the Art Institute building was home to the World Congress, and the plaster lions stood in other halls. When the museum moved into its current location a year later, Mrs. Henry Field had the beasts bronzed and donated to the art museum.” [Gaslin]

This erroneous origin story has seeped into scholarly works, such as a 2016 research article on Kemeys: “Today, outside the Institute’s doors still stands perhaps Kemeys’ best-known work: a sentinel pair of African lions, sculpted for the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 and now an important symbol of the city.” [Neely 119] Another art history monograph, discussed in Part 2 of this article, embellishes the narrative with additional meaning. [Wagner 178–79]

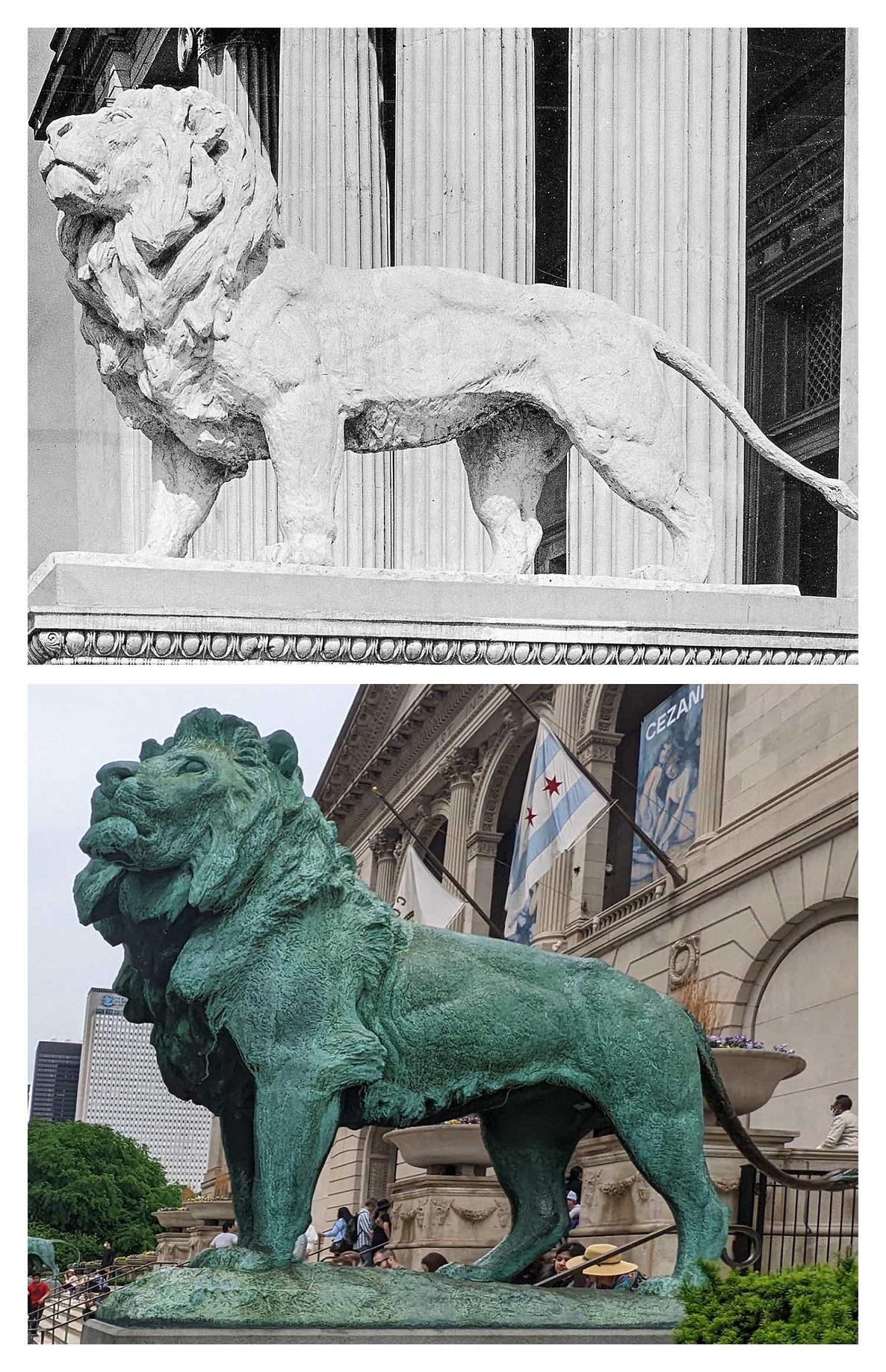

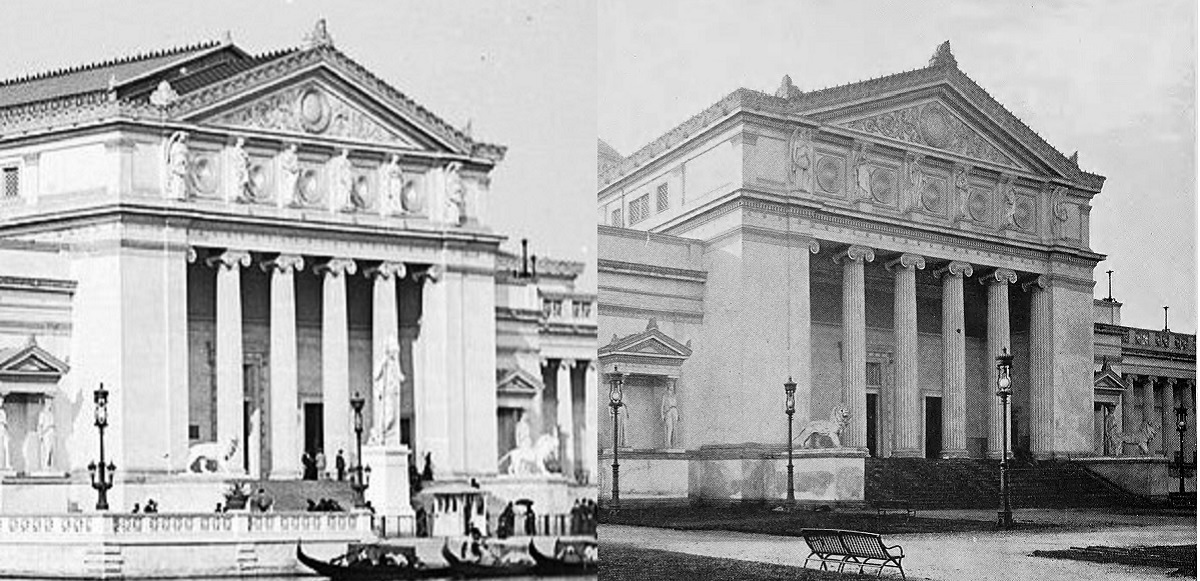

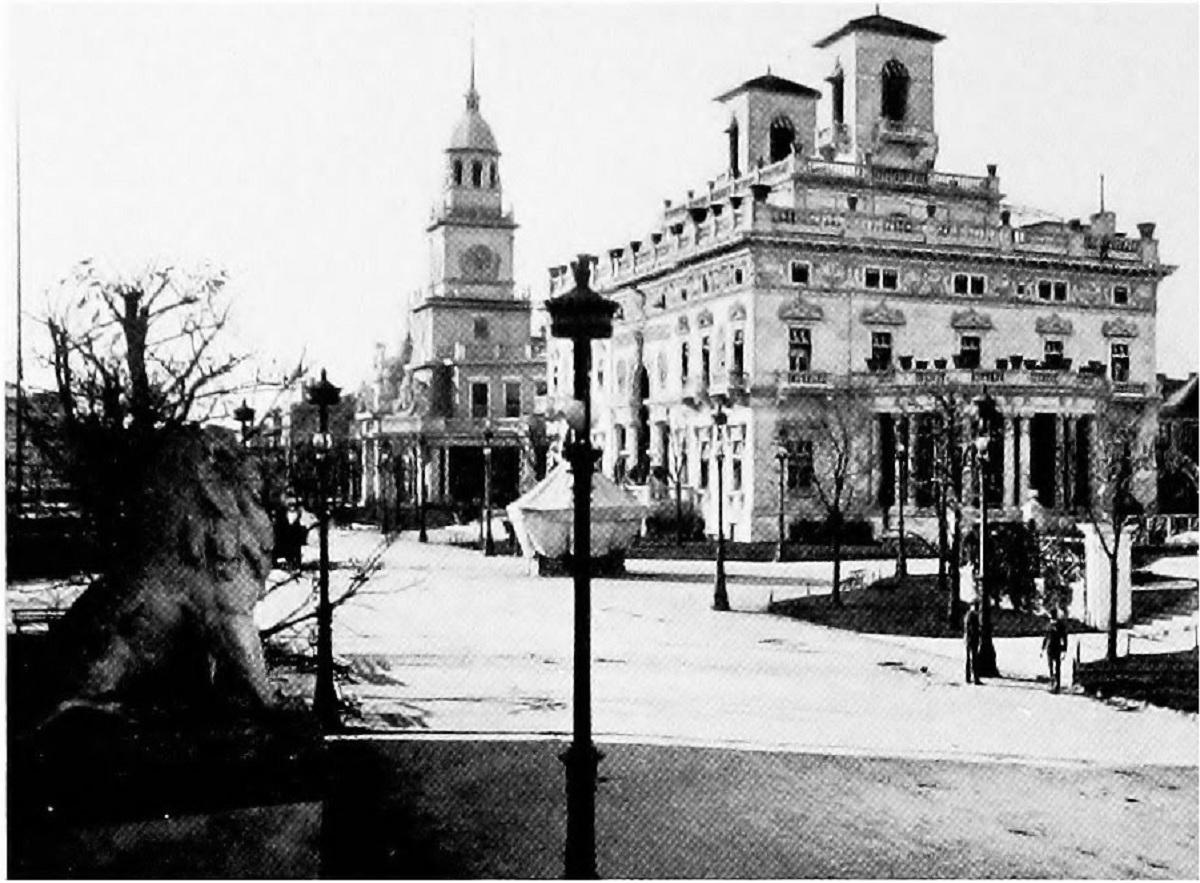

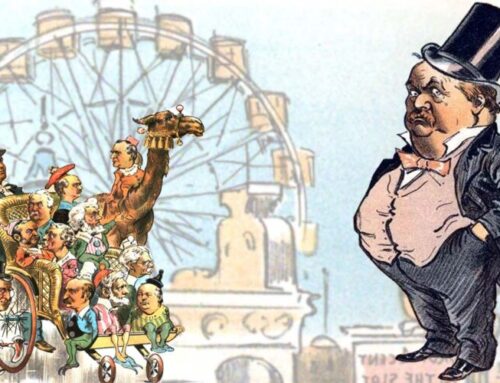

FIGURE 3: (TOP) A staff lion in front of the Palace of Fine Arts at the World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE) in 1893. [Image from private collection.] (BOTTOM) A different bronze lion stands in front of the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) in 2022.

Their lineage is not entirely clear

What is the origin of this account? The widespread notion that the Art Institute lions were cast from a pair of lion sculptures at the 1893 World’s Fair seems to have emerged almost a century later. The plaster quickly hardened on this misconception, and the myth—now cast in bronze—stands on a pedestal in Chicago lore.

One common source for the lion origin story told and retold around the city today appears to be “The Art Institute’s Guardian Lions,” a 1988 paper by Jane H. Clarke. “The general perception has long been that the Art Institute lions were derived from two lions by Kemeys which stood at the north entrance of the Palace of Fine Arts at the World’s Columbian Exposition … But their lineage is not entirely clear,” offered Clarke cautiously, when she served as Associate Director of Museum Education at the AIC. [Clarke 48] Using archival materials, she synthesized a valuable history of Edward Kemeys’ commission to sculpt the AIC lions. Unfortunately, this seminal paper contains an error (discussed below) that has since been amplified and enshrined by numerous others.

The lineage of the lions has not been at all clear. The tenuous connection between the AIC lions and the WCE lions strains under the weight of two important inconsistencies. First, there is almost no evidence that Kemeys sculpted a pair of lions for the 1893 World’s Fair. Second, the design of the two AIC lions clearly do not match those of the WCE lions.

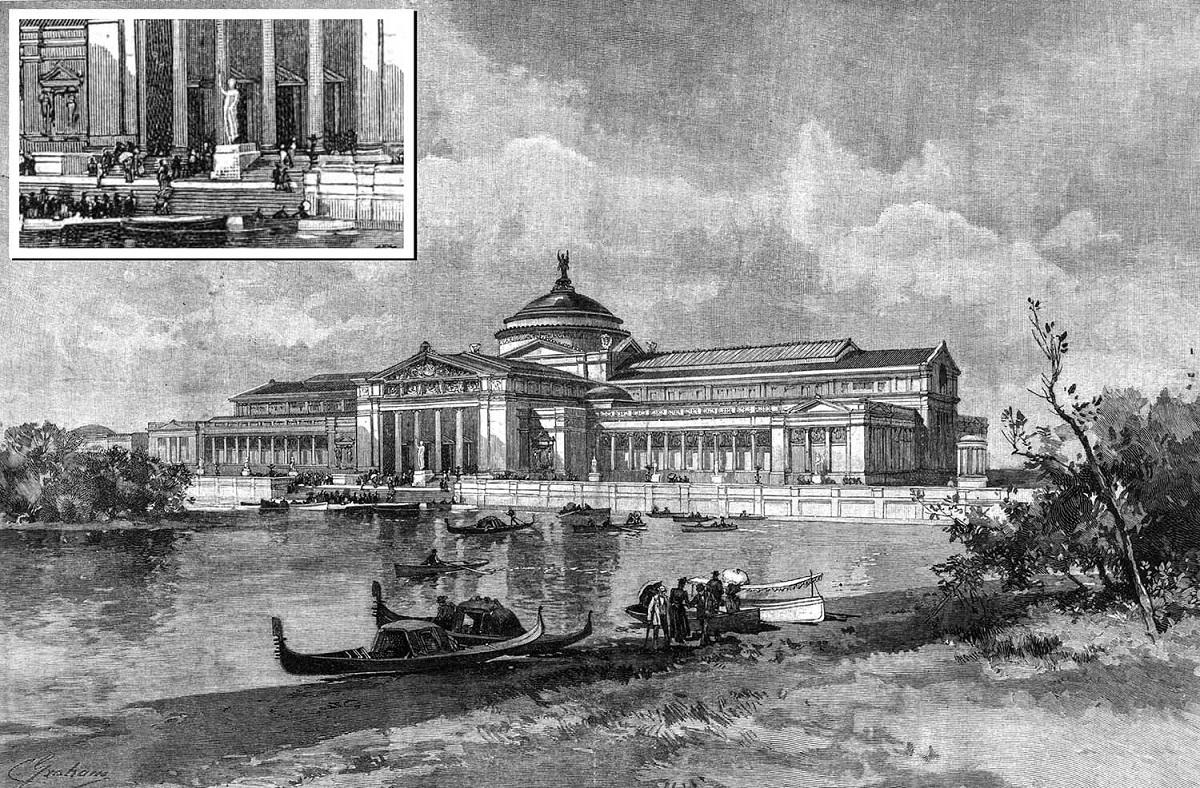

FIGURE 4: (TOP) A drawing by Charles Graham in 1891 does not show lion sculptures in front of the south entrance of Charles Atwood’s Palace of Fine Arts (see inset). [Image from Harper’s Weekly Sept. 5, 1891, p. 681.]. (BOTTOM) By April 1892, lions are included in a color rendition of the building then under construction. [Image from World’s Columbian Exposition Illustrated, Apr. 1892.]

Commission for the World’s Fair lions

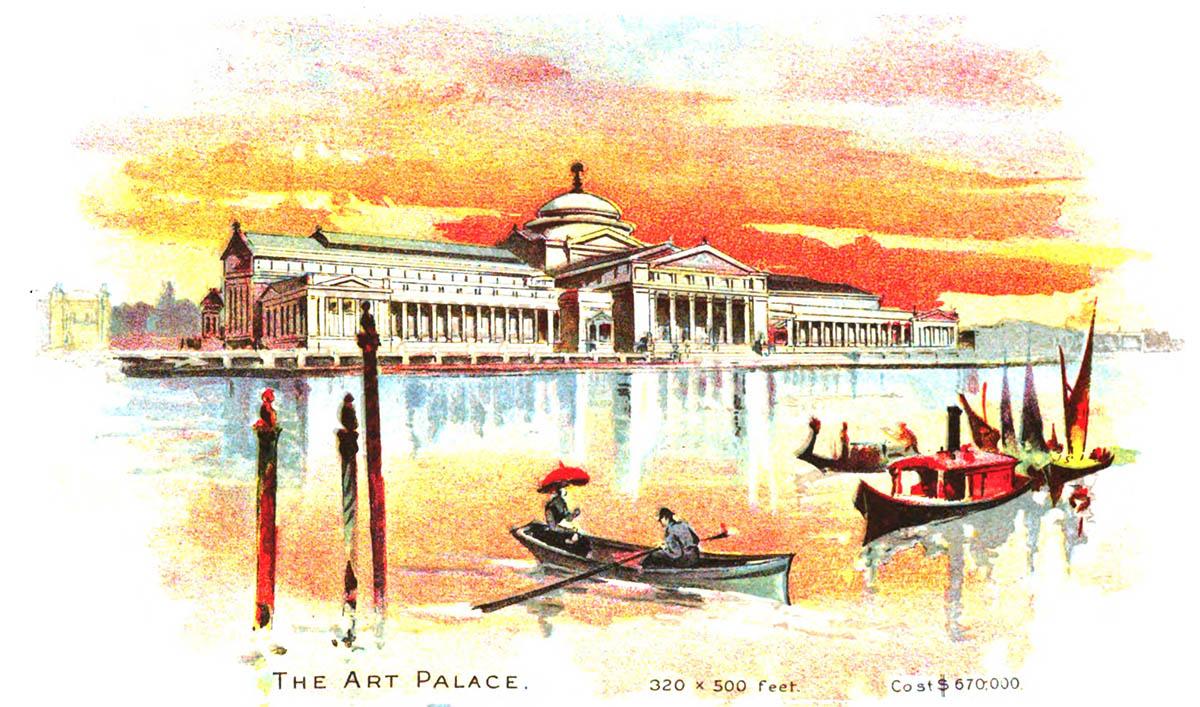

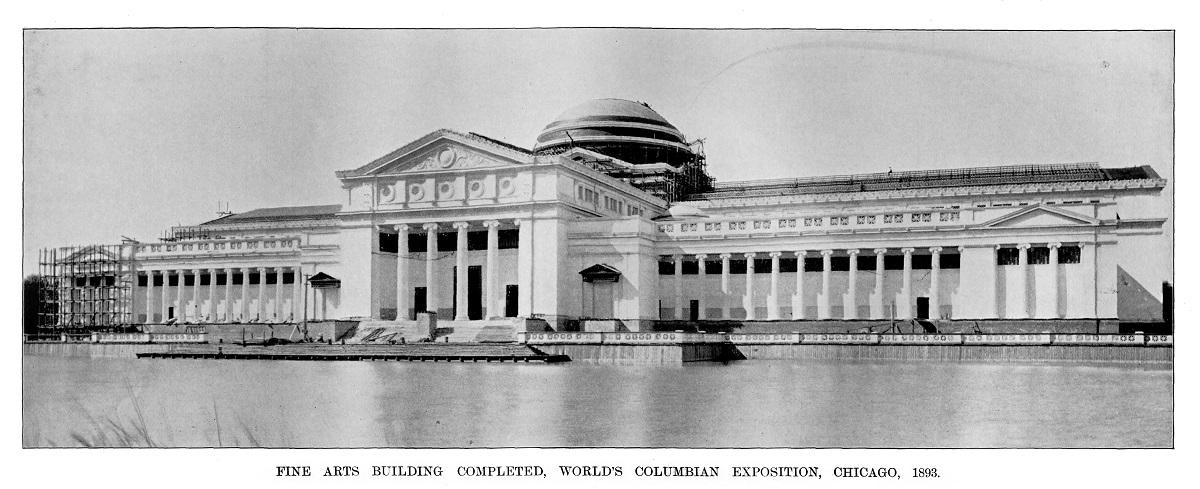

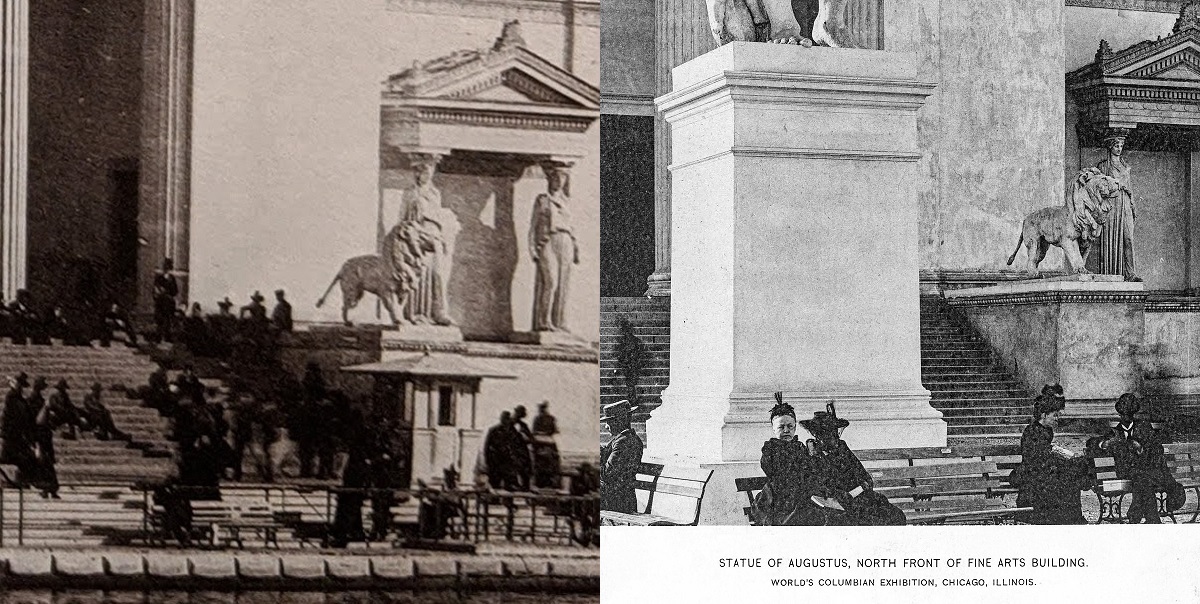

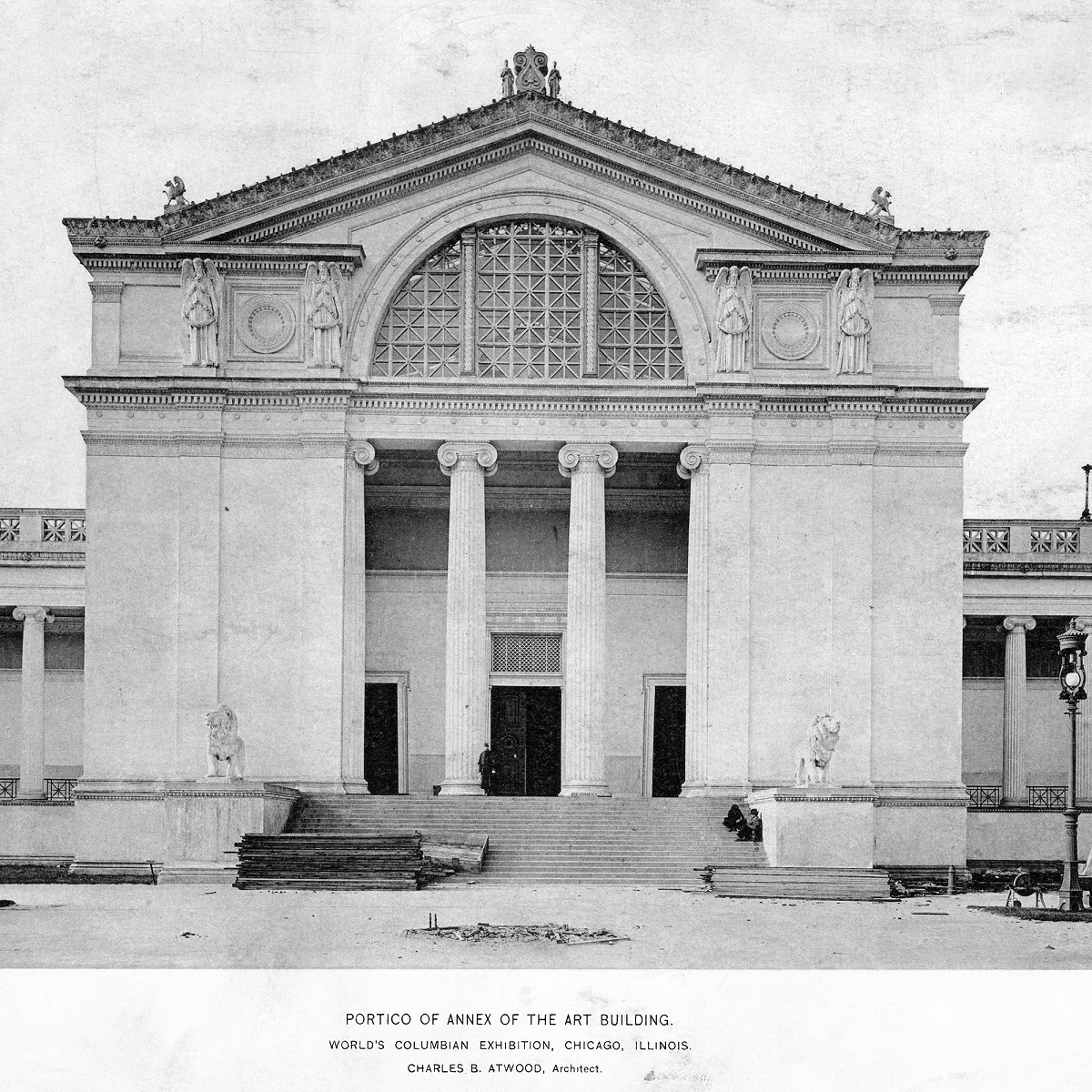

When Charles B. Atwood arrived in Chicago in April of 1891, he was almost immediately appointed Architect-in-Chief for the Columbian Exposition by Director of Works Daniel Burnham. Atwood designed more than sixty buildings for the Fair, but almost nothing in his productive output compared to the magnificence of his Palace of Fine Arts (also called the Art Palace, the Galleries of Fine Arts, and other names). One of the early renderings of the proposed building, published in the fall of 1891, does not show lion sculptures flanking the front entrance. (Oddly, Clarke indicates that this image, reproduced in Figure 4, includes “a pair of lions at the entrance.” [Clarke 49]) By April 1892, lion sculptures appear in sketches of the building (see Figure 4).

The Palace of Fine Arts at the Columbian Exposition, standing almost complete by December 1892, but without lions and other sculptural ornamentation. [Image from World’s Columbian Exposition Illustrated Dec. 1892.]

Just three weeks earlier, the Art Institute of Chicago had announced a major donation to fund two bronze lions for the front entrance to their museum (see Part 2 of this article). These AIC lions would be sculpted by artist Edward Kemeys, who at that time was also working on other sculptures for the Fair. [“The Fine Arts”] The histories of these three sculptors and these three lion commissions have become entangled in recent years. The purpose of this article is to establish authorship of each of the WCE lion sculptures and to correct the origin story of the AIC lions.

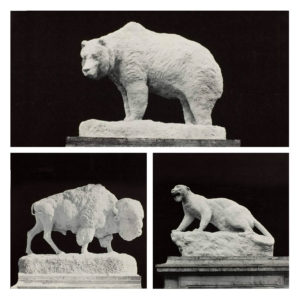

FIGURE 6: Edward Kemeys’ grizzly bear, buffalo/bison, and panther sculptures. [Image from Archival Image Collection, Ryerson & Burnham Archives.]

A plaster menagerie on the fairgrounds

Among the large group of sculptors decorating the buildings and grounds of the Columbian Exposition, the two most closely associated (and frequently confused) are Edward Kemeys and A. P. Proctor. Their suite of American wildlife sculptures adorned the bridges and landings along the Grand Basin and Lagoon. These, and nearly all of the outdoor sculptures for fairgrounds (as well as most building exterior surfaces), were made of “staff,” a mixture of plaster and hemp or jute fibers that when wet could be applied onto armatures and dried hard. This convenient material allowed for rapid production of sculptures intended to last only for the six months of the Fair.

Kemeys created six animal sculptures: male and female pairs of buffalo/bison, grizzly bears, and panthers. Proctor made eight animal works: pairs of moose (two copies of each), polar bears (two copies of each), jaguars (two copies of each), and elk (four copies of each), for a total of twenty sculptures. Proctor also prepared two equestrian statues, one of an Indian on horseback and the other of a Cowboy on horseback. Since 1893, sources have incorrectly counted the animal sculptures, failed to discriminate between the two sculptors, or misidentified some of the animal subjects (often confusing Kemeys’ panthers and Proctor’s jaguars). A census of these and other sculptures around the waterways of the 1893 World’s Fair is available at https://worldsfairchicago1893.com/home/fair/fairgrounds/sculptures/.

Theodore Baur (sometimes spelled “Bauer”) contributed a set of human figures for the top of the Peristyle and a rather strange sculpture called The Secret or The Sphinx.

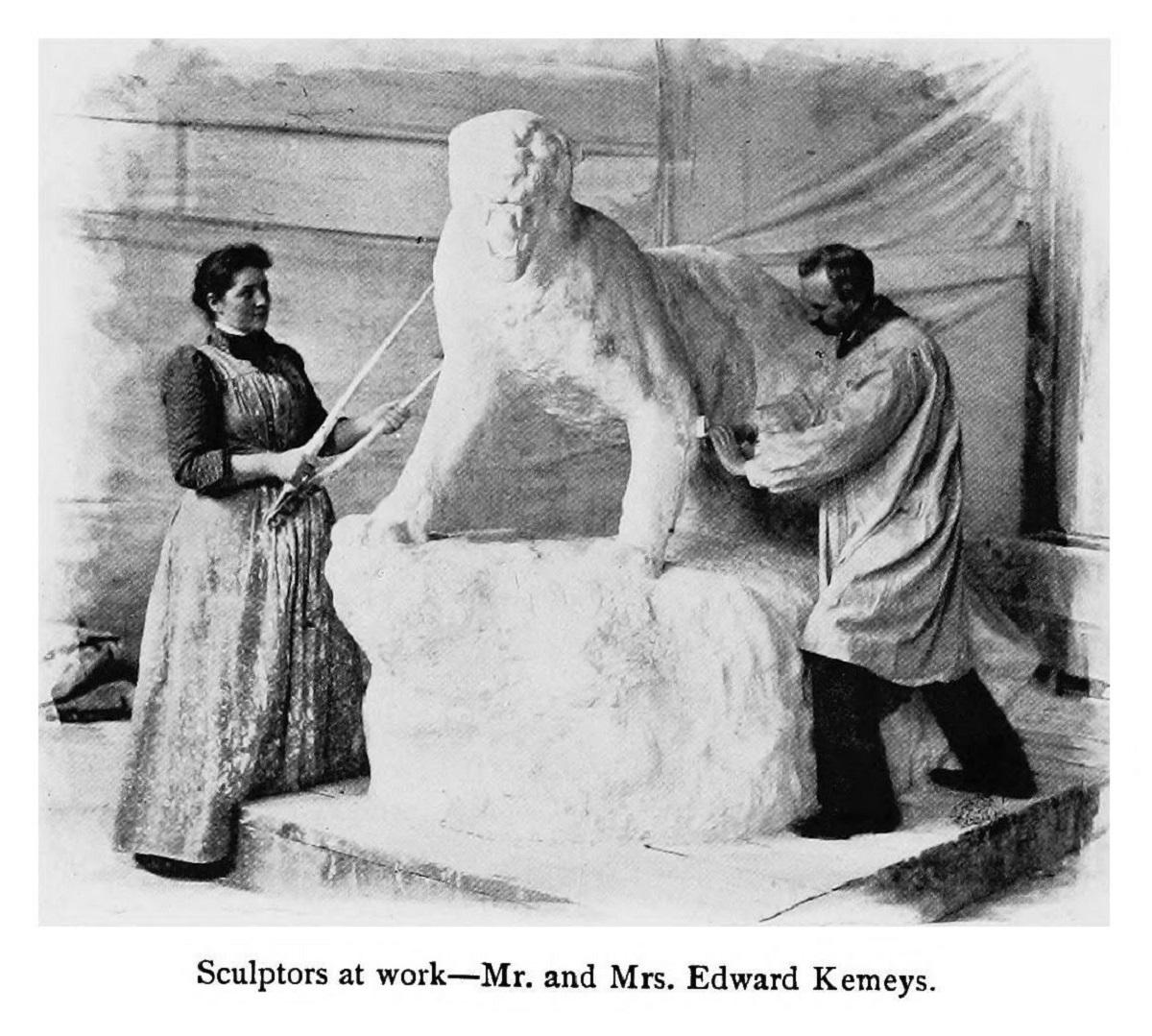

FIGURE 7: Edward Kemeys worked closely with his wife Laura on his sculptures for the 1893 World’s Fair. Shown here is one of the panthers (At Bay) that would be installed at the west end of the Manufactures Bridge. Perhaps contributing to the confusion and misattribution of the lions at the Art Palace, this work was sometimes referred to as a “lioness.” [Image from Johnson, Rossiter A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Held in Chicago in 1893, Volume 1: Narrative. D. Appleton and Co., 1897; this photograph was printed in the Jan. 21, 1893, issue of Harper’s Bazaar, indicting the work was completed before that date.]

[Addendum Jan. 18, 2025: The Chicago Record on April 5, 1893, noted that “A. Phenister [sic] Proctor, the talented Colorado animal sculptor, has just completed his second lion for the decoration of the entrance of the art building. The majestic king of beasts now stands guard over over the little studio in the north end of the horticultural hall.”]

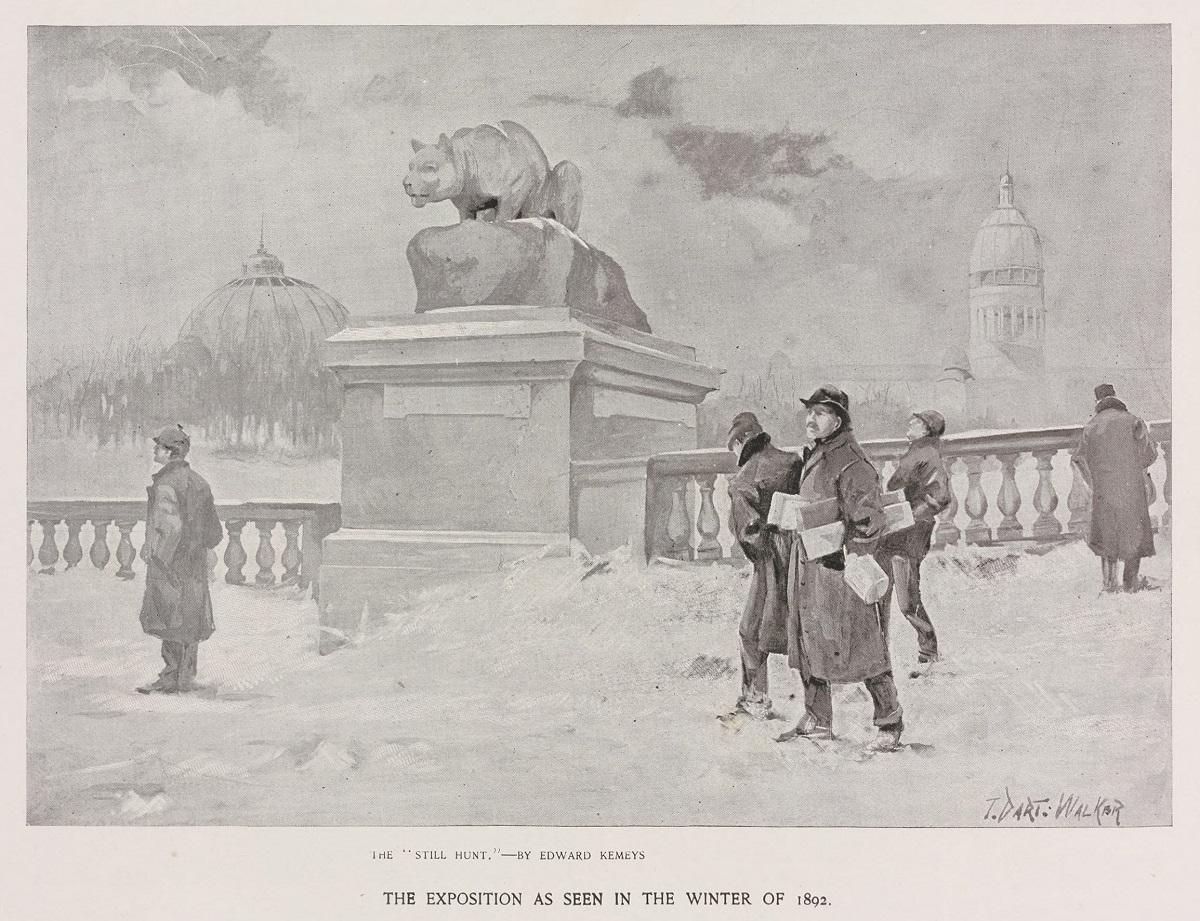

Because the commission for the lion sculptures around the Palace of Fine Arts came later (January 24, 1893), these likely were installed later than the American wildlife sculptures around the waterways. A sculpture that stood only temporarily on the central dome, Philip Martiny’s Victory, can be used to roughly date some images of the Art Palace, as it seems to have been installed sometime in April 1893. A few images of the building show Victory without the lions below, suggesting that the lions were not installed until around the time of the May 1 opening of the Fair.

A few other lion statues that decorated the fairgrounds should be noted before focusing on those around the Palace of Fine Arts. Four identical massive lions by German sculptor M. Arthur Waagen sat at the base of the Obelisk in the South Canal. Flanking the main entrance to the New York State Building were two standing lions, described as casts of the famous Barberini lions.

FIGURE 8: By the winter of 1892–83, one of Edward Kemeys’ panther sculptures (The Still Hunt) was completed and installed on the west end of the Manufactures Bridge. Native animal sculptures by Proctor also are featured in other photographs and illustrations from the winter months. [Image from The Graphic History of the Fair. Graphic Co., 1894.]

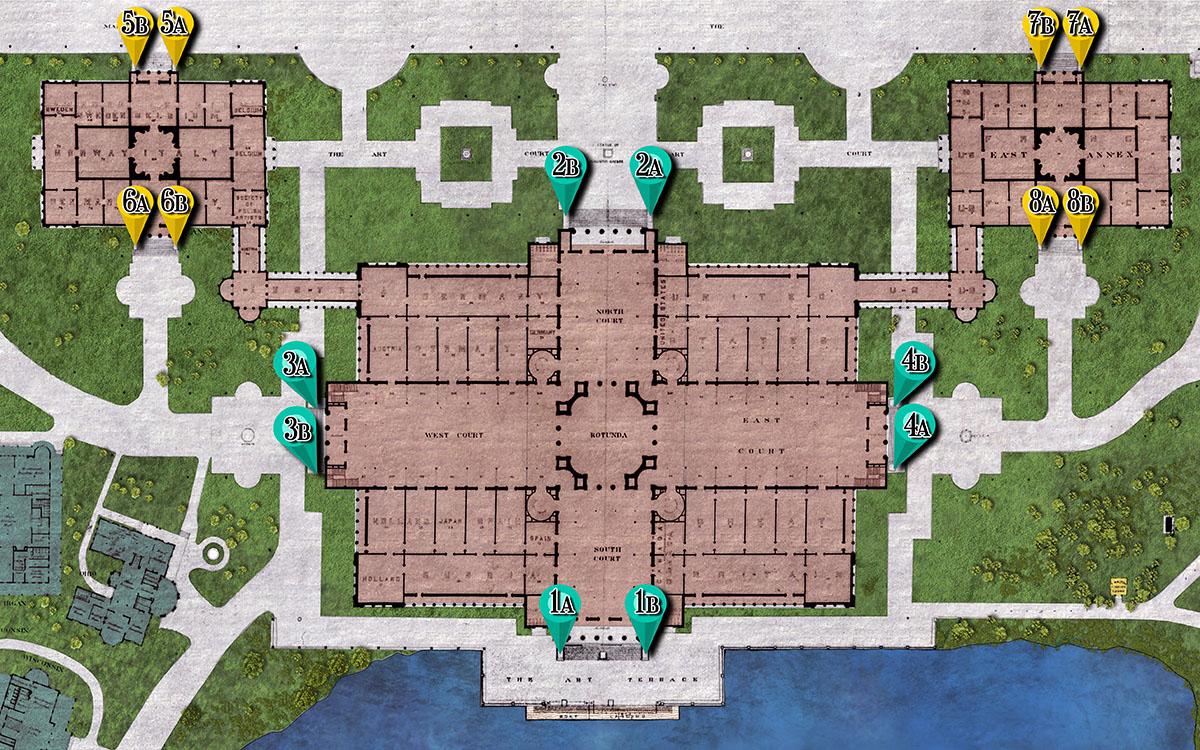

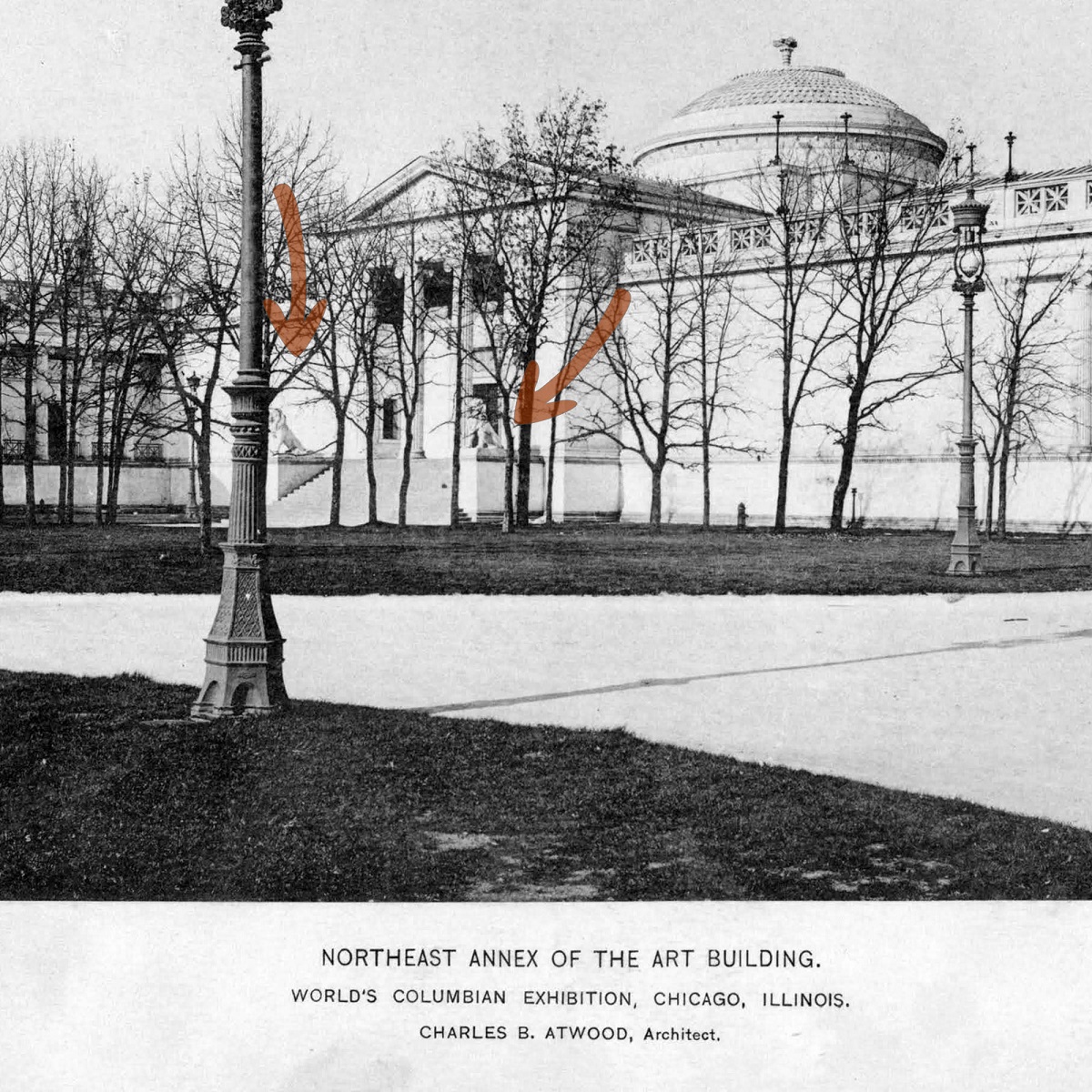

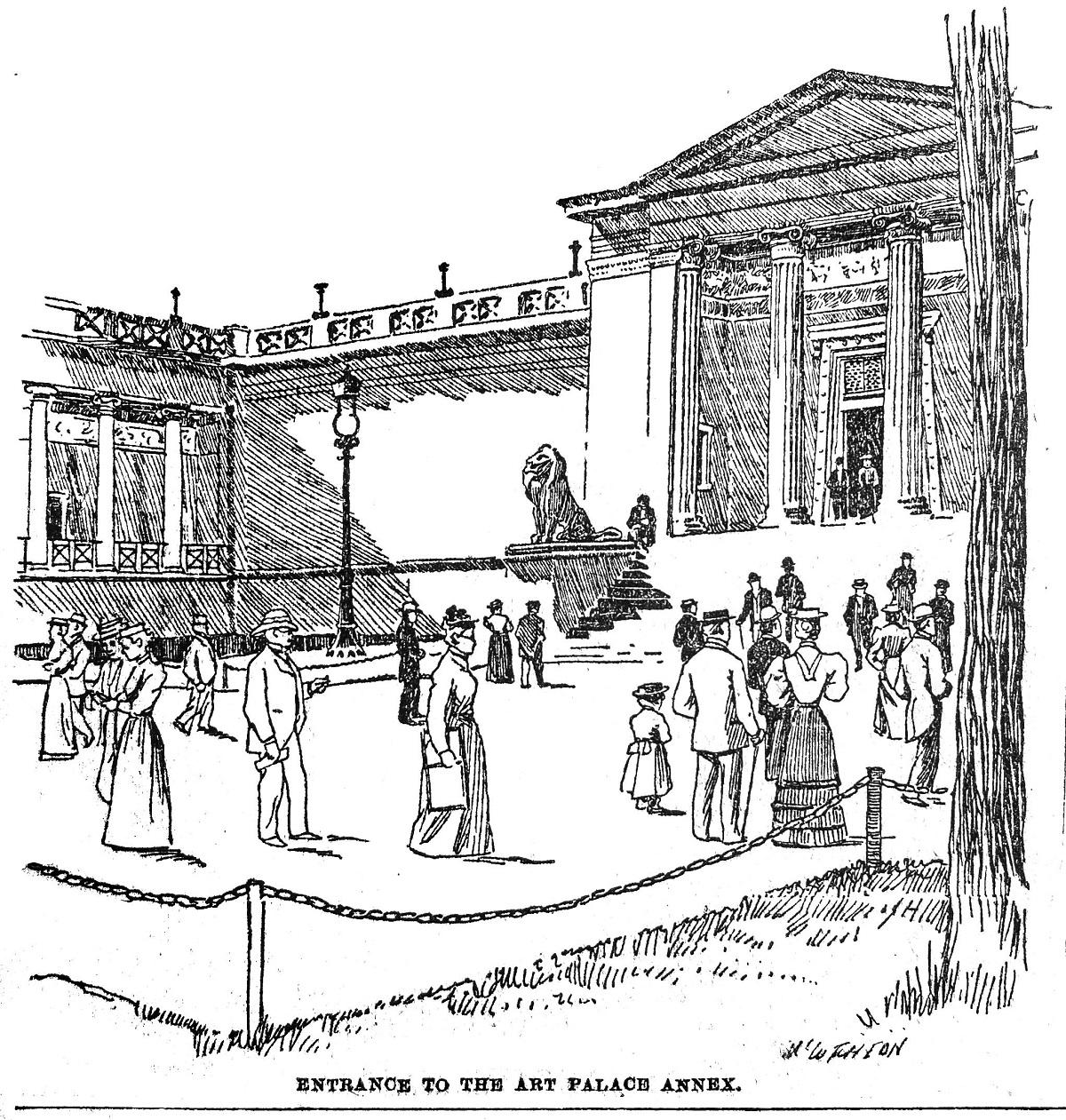

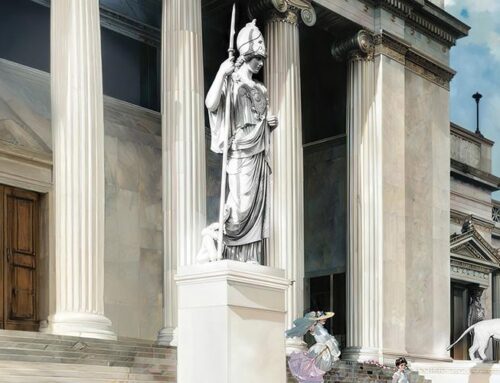

Guarding the Art Palace

A pair of lions stood on pedestals at each of the entrances to the Palace of Fine Arts. The building consisted of a Central Pavilion and two Annexes, as shown in Diagram 1. The reconstructed building that today serves as the Museum of Science and Industry has a nearly identical exterior footprint. In 1893, the “front” and main entrance of the Art Palace faced south, towards the North Lagoon. The Central Pavilion had four entrances (south, north, west and east), while the West Annex and the East Annex each had a north and south entrance.

Eight entrances were guarded by eight pairs of lions. Modern sources stating that there were only six pairs of lions may be getting this from Clarke, whose description of the building contained some errors: “Six pairs of lions guarded the entrances: one pair each at the principal, south entrance and at the secondary, north entrance, as well as a pair at the east and west entrances of the building’s two annexes.”[Clarke 51] The east and west entrances to the Central Pavilion are not included in her count, and the entrances to each of the Annexes were on the north and south sides (Diagram 1).

While no known contemporary source clearly enumerates the lion sculptures at the 1893 WCE, inspection of numerous photographs and artwork confirms that the Art Palace had eight locations for sixteen lions.

DIAGRAM 1: The Palace of Fine Arts, showing the locations of the eight pairs of lions, labeled A (left side) and B (right side) facing each entrance. Sculptures 1–4 for the Central Pavilion are attributed to A. Phimister Proctor. Sculptures 5–8 for the West Annex and East Annex are attributed to Theodore Baur.

Reporting on the lions

In addition to the news reports announcing the commission, documentation from the World’s Fair directors also attributes the lion sculptures for the Palace of Fine Arts to Proctor and Baur. Primary evidence comes from the Final Official Report of the Director of Works of the World’s Columbian Exposition.

In their reports to Daniel Burnham, two directors offered clear attributions of the lion sculptures. Superintendent of Buildings W. D. Richardson records that “at the entrance of the main building are the standing lions of Mr. A. P. Proctor, whose other works are to be seen in the groups about the bridges,” and that Theodore Baur’s “reclining lions” stood at the doorways of the Pavilions (Annexes). [Burnham IV, 41]

Francis Millet, Director of Decoration and Function, confirms these assignments in his report, writing that Mr. Proctor executed the lions for the main pedestals of the Art building [Burnham IV, 59–60] while Theodore Baur was “given a contract to model lions for the pedestals of the Annexes of the Art building” [Burnham IV, 60] and “executed the lions for the steps at the entrances to the Annexes of the Fine Arts building, a symmetrical pair repeated four times.” [Burnham IV, 68]

These directors, who supervised the contracts with numerous artists and the execution of their sculptures at the Fair, did not name Edward Kemeys as the creator of any pair of lions for the Palace of Fine Arts.

Also crediting the lion sculptures to Proctor and Baur are numerous contemporary World’s Fair histories, including White and Igleheart’s The World’s Columbian Exposition Chicago 1893 [White 71, 335], The Dream City [Portfolio 6], and J. W. Buel’s The Magic City.

A few books from the time of the Fair mention Proctor but not Baur. A guidebook from Rand, McNally notes that “the treasures in the Fine Arts Building are guarded by kingly lions, the work of Mr. Proctor.” [Week at the Fair, 96] Cameron’s The World’s Fair Being a Pictorial History of the Columbian Exposition also credits only Proctor. [Cameron 709] Art Treasures from the World’s Fair offers this description of the lion sculpture shown in Figure 9:

“When A. P. Proctor was given the contract for the lions that guard the entrances to the Art Palace—now the Columbian Museum—his heart must have swelled high within him. For this was generally considered to be the most beautiful and most dignified of all the superb buildings of the White City, and so to entrust so young a man with its most noticeable sculptural decoration was indeed to do him great honor. The lions flank the stairways at both of the main entrances, north and south. A piece of sculpture in such a position must partake of architectural rigidity without losing sculptural grace; it must not be in lively action, nor must it be tame. Those who remember Mr. Proctor’s imposing lions will probably consider that he successfully solved the problem.” [Art Treasures 43] In The Official Directory of the Worlds Columbian Exposition, Chief of the Department of Publicity and Promotion Moses P. Handy compiled a list of the statuary at the Fair. For the exterior of the Galleries of Fine Arts, he includes the sculptural works contributed by Philip Martiny and Olin L. Warner, but does not name the sets of lions or their authors, possibly because of their relatively late addition to the building’s ornamentation program. [Handy 203] Perhaps pulling from Handy’s official releases, Rossiter Johnson also omits mention of the Art Palace lions in his list of sculptures and artists published in Volume 1 of his monumental History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Held in Chicago in 1893. [Johnson V1 178‑80] Similarly, no lions are noted among the Art Palace statuary listed in Conkey’s Complete Guide to the World’s Columbian Exposition or in Truman’s History of the World’s Fair. On many details about the Exposition, various guidebooks and histories simply reprinted information supplied by Handy’s active publicity office.

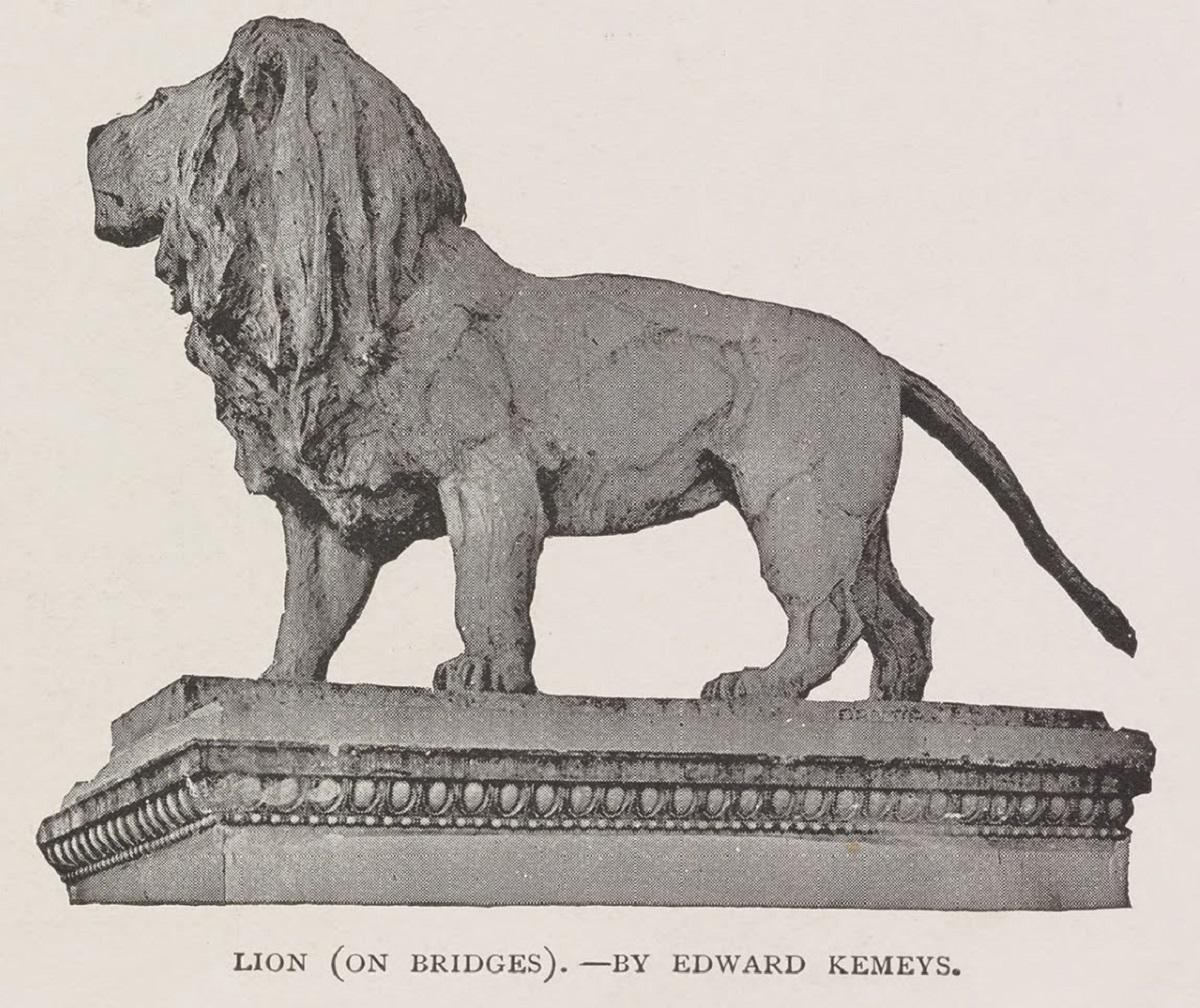

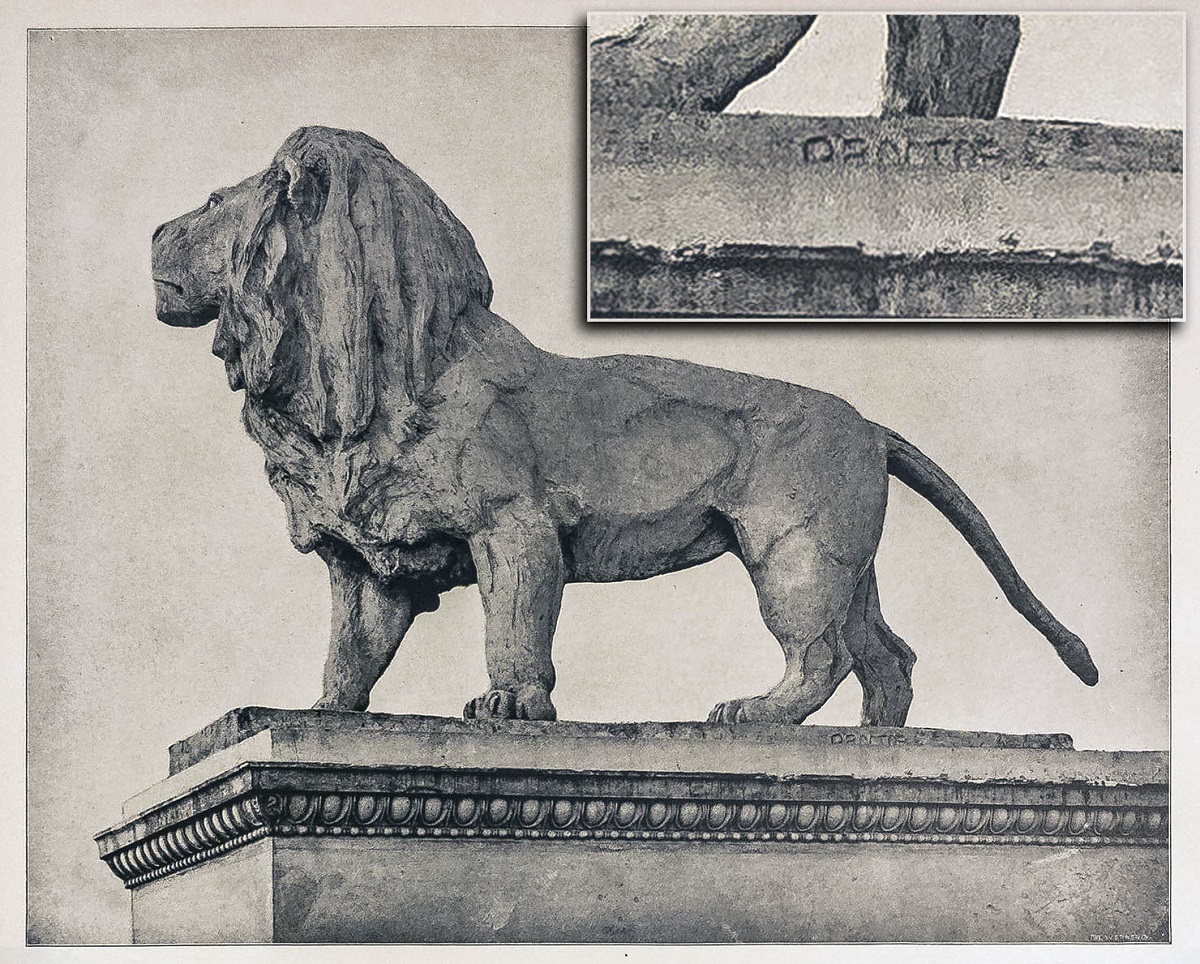

FIGURE 9: (TOP) Keeping track of the plaster menagerie at the 1893 World’s Fair posed a challenge. This photograph of one of Proctor’s lions for the Palace of Fine Arts is incorrectly labeled “Lion (on Bridges) by Edward Kemeys.” The same source also incorrectly attributes one of Proctor’s moose sculptures to Kemeys. [Image from The Graphic History of the Fair (Graphic Co., 1894).] (BOTTOM) What is clearly the same photograph of the same lion sculpture is correctly attributed to A. P. Proctor in the caption (partially reprinted in text below). An inset shows the signature by Proctor on the base. (This is the “A” lion made for the four entrances to the Central Pavilion.) [Image from Art Treasures from the World’s Fair (The Werner Company, 1895).]

Did Edward Kemeys author a pair of lions for the 1893 World’s Fair?

There is almost no evidence to support this claim.

The major source of confusion, which seems to be the ultimate basis of the erroneous account about Kemeys’ AIC lions, is one statement in Volume 2 of Johnson’s History, in which he writes that “the Central Pavilion was entered by four great portals … The lions that guarded the north entrance were the work of Edward Kemeys, and those that guarded the south entrance were by Theodore Bauer [sic].” [Johnson V2 383] Both parts of this statement are refuted by nearly every other source, not to mention Proctor’s visible signature on the sculpture.

Only two other contemporary sources have been discovered that attribute the WCE lions to Edward Kemeys. One is a figure caption in The Dream City [Portfolio 13] which states that the lions for the Art Palace “were made by Edward Kemeys and Phimester [sic] Proctor” (contradicting what is written in Portfolio 6). The other is a photograph of a lion labeled “Lion (on Bridges) by Edward Kemeys” even though Proctor’s signature is visible on the base (shown in Figure 9).

As noted above, this sort of confusion was not unique to the Palace of Fine Arts lions. Many examples can be found of reporters, critics, and contemporary historians either failing to discriminate between the wildlife sculptures of Proctor and Kemeys located around the Grand Basin or misidentifying either the sculptor or the animal subject.

Rossiter Johnson’s (mis)statement that Kemeys sculpted the north-entrance lions seems to be the sole basis of Jane H. Clarke’s account in her 1988 paper that Kemeys’ lions for the AIC may have originated at the WCE. This incorrect attribution continues to propagate in both popular and scholarly literature.

There is a bigger piece of evidence, however, that refutes this connection: the forms of the WCE and AIC lions do not match!

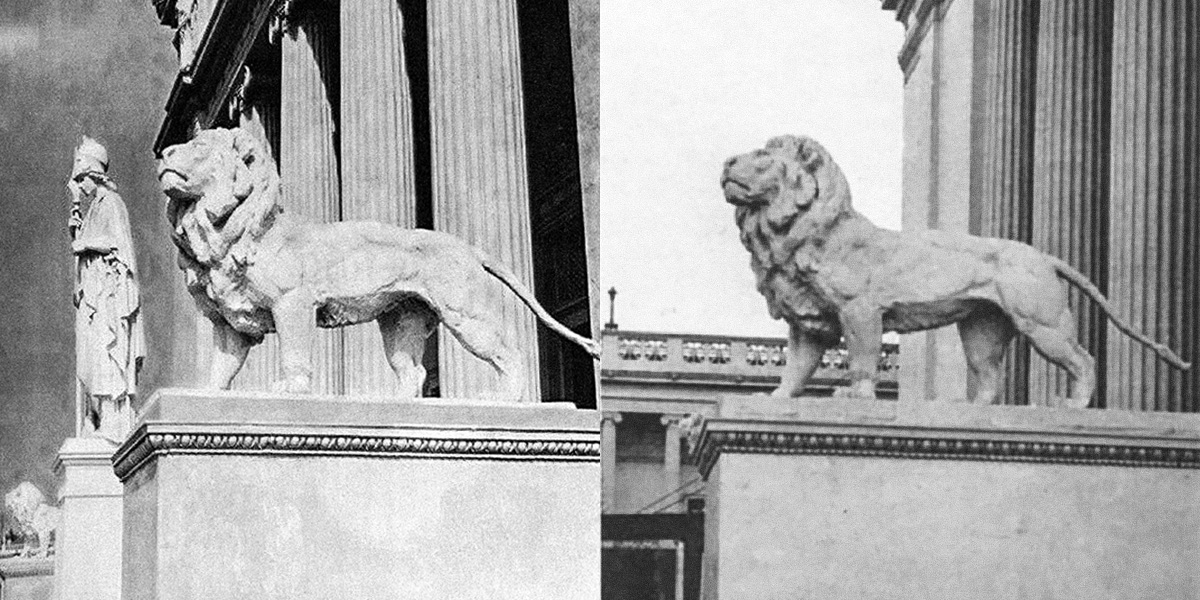

FIGURE 10: A. Phimister Proctor’s Lion sculpture for the Central Pavilion of the Palace of Fine Arts at the 1893 World’s Fair. (LEFT) The lion standing at the south entrance (1B), with the reproduction of Minerva visible behind it. [Image from private collection]. (RIGHT) The lion standing at the north entrance (2B), with the western wall of the East Annex visible behind it. [Image from Clarke.]

A plaster pride of sixteen lions

Hundreds of photographs, paintings, and drawings depict the Palace of Fine Art at the 1893 World’s Fair. Most show the main, south-facing, entrance that was flanked by lions. Far fewer images show the north, west, and east entrances to the Central Pavilion or the north and south entrances to each of the Annexes and their accompanying sets of lions.

Comparing images of many of these sixteen WCE lions and the two AIC lions reveals both important differences and similarities that can help assign their authors. The forms of lions possess distinct variations in the position the of head, stance of the legs, and shape of the tail.

First, the two lions at any given entrance of the Central Pavilion of the Art Palace are not mirror images of each other. The lion on the left-side pedestal poses with head up and pointed to its right (with mouth closed) and stands with its right-front and left-rear paws forward, and the tail points straight back and down. The lion on the right-side pedestal poses with head up and pointed to its left (with mouth closed) and stands with its right-front and right-rear paws forward, and the tail points straight back and down.

FIGURE 11: (TOP LEFT) The Palace of Fine Arts south entrance, showing one of Proctor’s lions (1B). (TOP RIGHT) A copy of the same lion (2B) is visible in this view of the north side of the Palace of Fine Arts. [Cropped images from American Architect and Building News Mar. 3, 1894; E. R. Walker Photograph Album (c1893).] (BOTTOM LEFT) The Palace of Fine Arts south entrance, showing Proctor’s pair of lions (1A and 1B). (BOTTOM RIGHT) Copies of the same pair (2A and 2B) stood at the north entrance. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair (The Bancroft Company, 1893).]

A second and most important observation is that the sculptures positioned at the north, west, and east entrances of the Central Pavilion appear to be the same pairs of lions. In her article, Clarke reproduces images of one of the north pair lions (2B) and of the south pair but then draws the conclusion that they came from the hand of two different sculptors, despite being “strikingly similar.” [Clarke 55] A simpler explanation—consistent with both the WCE reports, histories, and photographs—is that the north-entrance and south-entrance lions are the same pair (see Figure 11). They were reproduced again for the west and east entrances of the Central Pavilion (Figure 12), though these other two pairs of lions are not mentioned by Clarke. Taken together, photographic evidence supports the conclusion that A. P. Proctor designed one pair of standing lions, and copies were placed at each of the four entrances of the Central Pavilion.

FIGURE 12: (TOP) The pair of lions (3A and 3B) that flank the west entrance of the Central Pavilion of the Palace of Fine Arts. [Image from a B. W. Kilburn stereoscope card.] (BOTTOM) The pair of lions (4A and 4B) that flank the east entrance of the Central Pavilion of the Palace of Fine Arts. (Note that the caption of this image incorrectly labels this as the Annex; the semicircular window in the pediment indicates that this is the Central Pavilion.) [Image from The American Architect and Building News, Jun. 9, 1894.]

FIGURE 13: Three depictions of Theodore Baur’s Lion sculpture for the Palace of Fine Arts at the 1893 World’s Fair. (TOP) One of the few photographs of the Palace of Fine Arts Annex shows Baur’s seated lion sculptures (8A and 8B) in front of the south entrance. [Image from The American Architect and Building News, Mar. 17, 1894]. (MIDDLE) An illustration from an unknown newspaper depicting the same view and providing a clearer image of the lion. [Image from private collection.] (BOTTOM) One of Baur’s seated lions at the north entrance of the East Annex (likely 7B) can be seen in the left edge of this vista of the State Buildings. [Image from Johnson, Rossiter A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Held in Chicago in 1893, Volume 4: Congresses. D. Appleton and Co., 1898.]

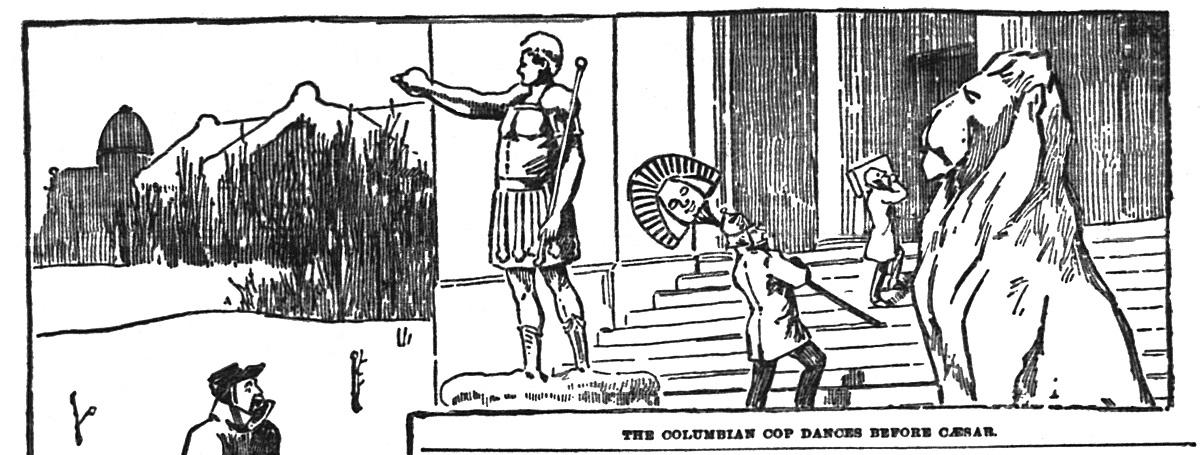

FIGURE 14: An illustration made by W. W. Denslow of Baur’s lion on the north entrance of the West Annex in the winter of 1894, after the close of the Fair as the building is converted into the Field Columbian Museum. (Denslow would illustrate Baum’s Cowardy Lion six years later.) [Image from the Chicago Herald Jan. 28, 1894.]

After the Fair

Journalist Julian Hawthorne was a close friend of Kemeys and wrote several critiques of the World’s Columbian Exposition. In one essay, he comments on Kemeys’ “grizzlies on the North Bridge, and the Bison on the South, and the Panthers on the bridge opposite the Main Building.” Knowing that the lions are not authored by Kemeys, he addresses them separately and with scorn: “It is good to know that The Palace of Art is not to be removed but will continue to educate and refine the world so long as the material of which it is made lasts, and afterward will be replaced with everlasting marble. And then, I trust, the Lions will be suppressed, or their places filled by the work of some stronger hand.” [Hawthorne 60]

After the close of the Columbian Exposition, the former Palace of Fine Arts building was converted into the first home of the Field Columbian Museum, where the staff lions continued to stand guard, while other ornamentation such as the south-side Minerva and north-side Caesar eventually were removed.

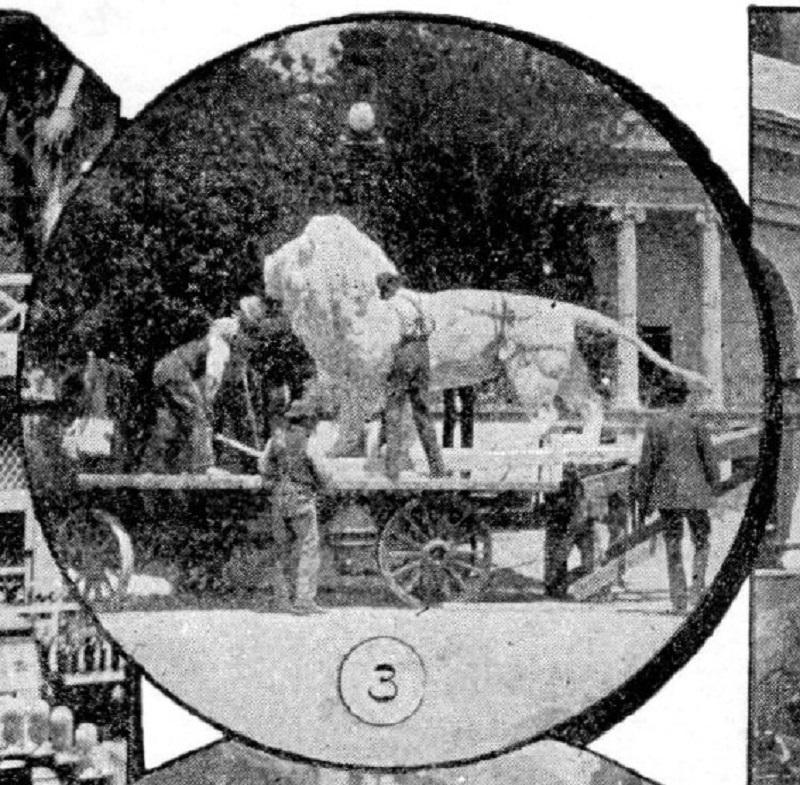

Proctor’s Lion (A) being moved to the Palace of Fine Arts. [Image from Demorest’s Family Magazine Sep. 1893.]

The success of Proctor’s sculptural works for the Columbian Exposition established his reputation as a leading American sculptor and earned numerous commissions in the coming years. And yet, the record of his World’s Fair lions seems to have vanished with his plaster sculpture. In his autobiography, written some forty years after the Columbian Exposition and containing more than a few inaccuracies about dates and locations associated with it, Proctor mentions his set of American native animal sculptures and his mounted cowboy and Indian scout statues, but neglects to note the colossal lions guarding the Palace of Fine Arts. [Proctor] A comprehensive monograph on Proctor’s sculptures, published in conjunction with the first major exhibition of his sculptures in 2003, also lacks any mention of the lions. [Hassrick]

Once Kemeys’ metallic monarchs took their place in downtown Chicago, Proctor’s lions were further obscured by the confusion of an erroneous origin story.

Continued in Part 2.

FIGURE 15: Proctor’s lions stood guard at the south entrance of the Field Columbian Museum until at least 1901. [Image from a postcard in the collection of the Library of Congress (cropped).]

Leave A Comment