Arriving unannounced and dressed in civilian clothing, United States government officials attempted to seize Russian assets in Chicago. In retaliation of the invasion, the Russians abruptly withdrew from a major international alliance. The year was 1893.

The World’s Columbian Exposition was a trade show on a colossal scale. Foreign countries and businesses sent to the World’s Fair in Chicago an enormous quantity of goods to display in the great halls of the White City. Though ostensibly exhibits, many of these items also were available for sale on site. This created a conflict because these goods often were declared as exhibits when they entered through U.S. ports in order to avoid customs duties. Once transactions ensued inside the fairgrounds, the U.S. Treasury went after some of the international exhibitors/vendors. The angriest quarry caught in such a trap was the Russian bear.

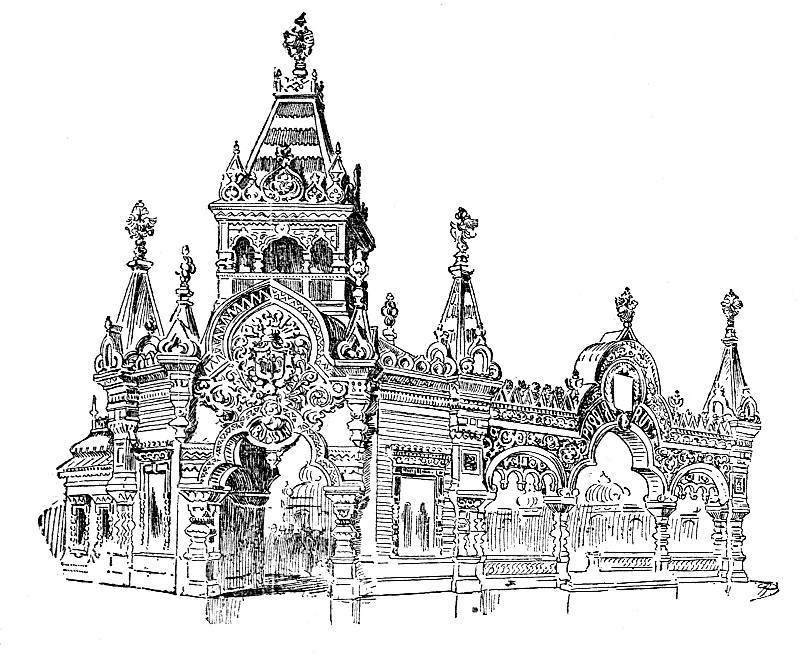

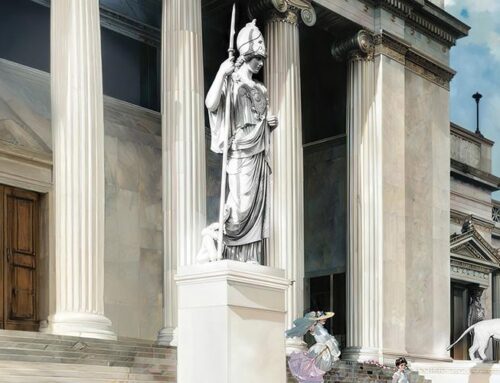

The grand entrance to the Russian pavilion. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

The Russian pavilion

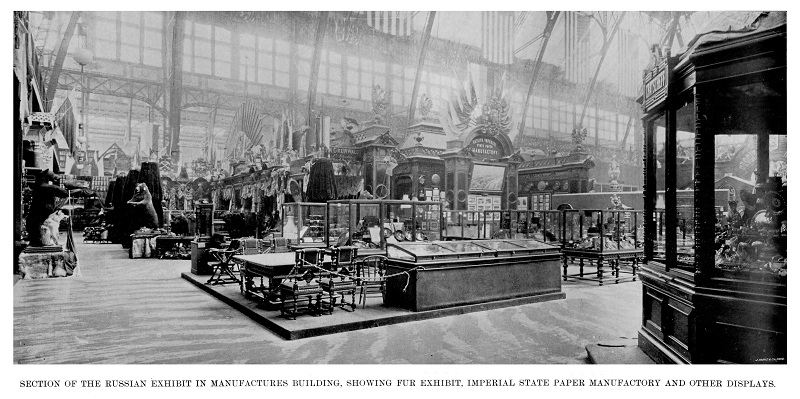

While foreign exhibitors displayed their products in each of the great exhibition halls of the World’s Fair—the Agricultural Building, the Anthropological Building, the Electricity Building, the Fisheries Building, the Forestry Building, the Horticultural Building, Machinery Hall, the Mines and Mining Building, the Palace of Fine Arts, the Transportation Building, and the Woman’s Building—none came close to matching the volume in the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building.

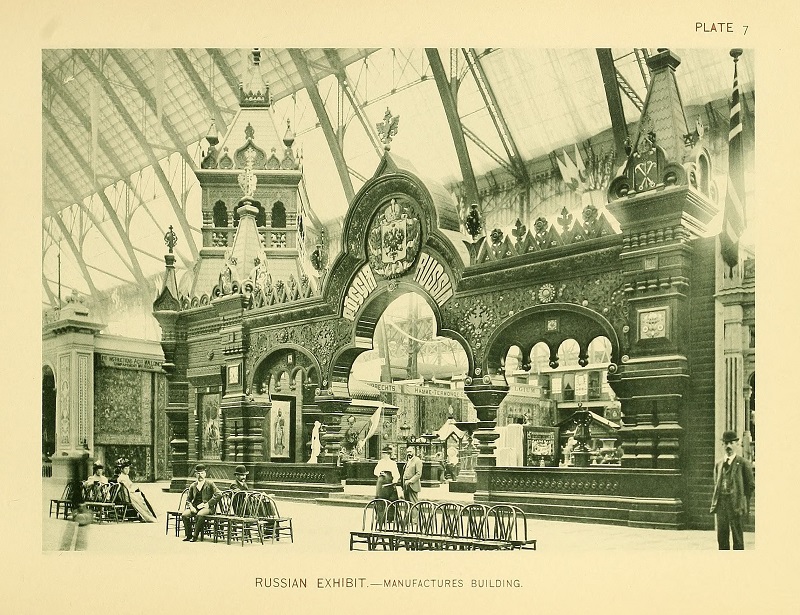

Inside this building—the largest in the world at the time—stood impressive pavilions erected by various nations and companies. Among the most magnificent was the Russian Pavilion, occupying almost one acre of exhibiting space in the southeast side of the building. With a grand entrance on the northwest corner facing Columbia Avenue, the imposing façade featured a decorative seventeenth-century ecclesiastic structure having a sixty-foot pinnacle surmounted by a Russian eagle. Designed by Ivan Ropet, the imperial architect to the Czar, the structure took inspiration from the palace at Kolomna, the childhood home of Peter the Great.

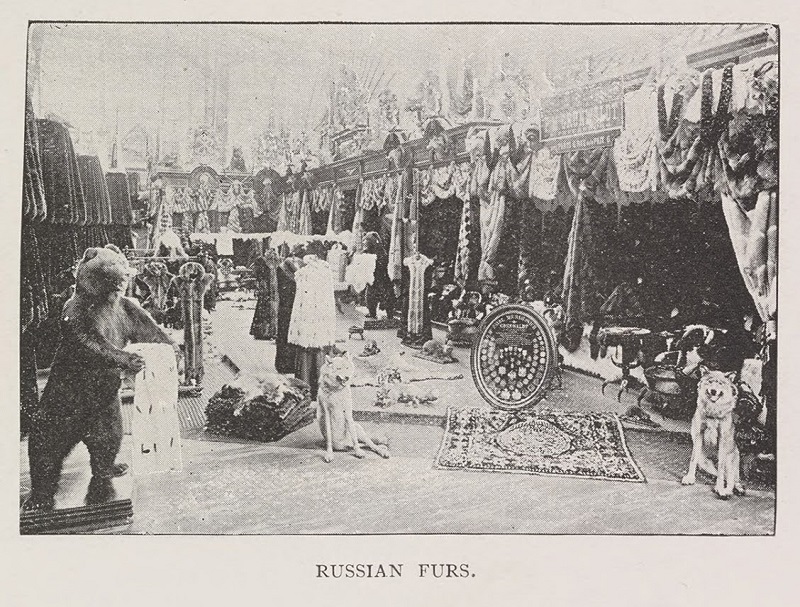

Inside the pavilion, hundreds of individual exhibitors from the leading businesses of the Russian empire displayed their goods: vases and urns, bronze sculptures, enameled silver pieces, jewelry and precious stones, furs, fine silks and textiles, leather goods, carved-wood furniture, hand-made rugs, and more. Much of it was for sale.

Serving as the Commissioner General for the Russian exhibits at the 1893 World’s Fair was His Excellency Imperial Chamberlain P. de Gloukhovskoy.

P. de Gloukhovskoy, Imperial Commissioner General of Russia to the World’s Columbian Exposition. [Image from Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume II. M. Juul & Co., 1894.]

A rough and insulting search

When the U.S. Treasury Department placed restrictions on the sale of foreign goods at the Fair, a storm erupted. The center of the tempest was the Russian section.

Undercover officers suspected that a Russian exhibitor had been selling bonded goods from his booth. Their specific target was either Mr. Lukutin (according to reporting by the Chicago Tribune), whose workshop in Moscow produced lacquered papier-mâché articles with paintings, or Mr. Sukertin from St. Petersburg (according to the Inter-Ocean newspaper). When the Customs Service sting unfolded, the exhibitor had been absent from Chicago for several days, but he had entrusted the keys to his display cases to Mr. Plar, an officer in the French army.

On July 20, several plain-clothed agents entered this exhibit space and demanded the keys from a workman whom they found there. They claimed to be Custom-House officers but offered no governmental identification. The workman referred the agents to Mr. Plar, who refused to unlock the cases without proof of their official authority and without the Russian Commissioners present. After being threatened with arrest and physical assault, he capitulated and surrendered the keys.

Commissioner Heard, an agent of the Russian Minister of War who oversaw a large portion of the Russian exhibit, arrived on the scene and submitted his protest to the Deputy Collector Hall of the U.S. Custom House on the fairgrounds. “He listened to me for a while with indifference,” reported Commissioner Heard, “and then asked me in what I considered an offensive tone who I was.”

An unsubstantiated rumor spread that U.S. Customs officials had torn down and trampled on a Russian flag. War clouds formed above the Russian pavilion.

The facade of the Russian Pavilion [Image from the Chicago Tribune, July 24, 1893.]

Not used to being bullied

“The incident is a painful one to us,” claimed Commissioner Heard, “as our government made its exhibit solely as a demonstration of our regard for the United States. Most of it belongs to the government and could not be purchased at any price.”

Commissioner-General Gloukhovskoy directed a letter to Mr. Clark, the Collector of Customs, asking that the U.S. customs officials be removed from the Russian section of the exhibit hall. Gloukhovskoy also addressed a letter to George R. Davis, Director-General of the Columbian Exposition, complaining about the seizure of goods.

Despite this being a conflict between Russian and U.S. governments, the Columbian Exposition administration intervened to smooth things over.

Director-General Davis explained the American position: “We can’t permit exhibitors to sell bonded goods in defiance of Customs regulations. The Secretary of the Treasury has made rules which are extremely liberal, and the foreign exhibiters must appreciate that they are to be enforced.” Davis conceded, however, that foreign exhibitors were entitled to apologies and assurances of immunity from further indignities of this sort, stating that U.S. inspectors should not “disregard the flag of a foreign country and unlock display cases without the approval of the foreign commissioners in charge.”

The Tribune agreed, publishing an editorial stating support for the Exposition’s position that bonded goods must not be sold at the Fair, but that enforcement need not be rough and insulting. “It is the simplest matter in the world to enforce the regulations without giving offense.” Many of the foreign governments involved in the dispute, they observed, “are not so well used to being bullied by underlings as Americans are and do not submit so patiently.”

One member of the Board of Directors of the Columbian Exposition took a more forceful stand against the Russians. Charles H. Schwab stated that foreign exhibitors who engaged space at the Fair “have signed a contract to abide by the rules and regulations. If they violate the rules, they must expect to suffer for it.”

A Russian bear on display in the fur section of the Russian exhibit. [Image from The Graphic History of the Fair. Graphic Co., 1894.]

The Russian bear was rampant

The American apology did not come quickly enough to avert a theatrical protest.

Indignation about the incident spread to other foreign commissioners in the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. “The Russian bear was rampant,” reported the Tribune, while the French commissioners were “effervescent as a glass of champagne.” They perceived that the sting operation on the Russian exhibit was an attack at the sale of foreign goods throughout the building.

The foreign commissioners collectively prepared a coup d’état against the American authorities, hoping “either to secure greater liberty in the sale of goods or else to plunge the entire Exposition into a cave of gloom.” In addition to demanding an apology, they gave their ultimatum to Director-General Davis.

The Russians closed shop, hermetically sealing their pavilion under canvas coverings. “A few of the exhibitors poked around in a sullen manner, to emphasize the funereal gloom,” noted the Tribune.

While the Russian section stayed open, and the official government exhibits remained uncovered in order to avoid a “political affair” with the U.S. government, the exhibit booths of Russian firms and individuals hid under the blankets. These exhibitors collectively made the decision to cover their displays, and the Russian commissioners supported their action.

The international dispute reportedly even reached government officials in Washington, but the State Department received scant details about the kerfuffle in Chicago. Soon enough the conflict on the fairgrounds subsided and Russia came out from under her covers on July 22.

The interior of the Russian exhibit in the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. [Image from Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume II. M. Juul & Co., 1894.]

Russians complacent

“The Russian bear, which erstwhile had stood on his hind legs and roared for gore, is now in a sitting posture, smiling from ear to ear, and complacently nodding acquiescence,” reported the Tribune colorfully. Calm intervention by Director-General Davis brought peace to the fairgrounds.

Russian commissioners acknowledged that their main complaint was simply about the American’s lack of courtesy. They expected to be present at a booth being inspected by the U.S. government officials and to be treated respectfully. Other foreign commissioners remained concerned about restrictive policies of U.S. Customs, which—on top of delays in getting their exhibits open, dissension over judging and awards, and “the silver excitement”—had deflated their enthusiasm for the World’s Fair. “If we had foreknown all this,” reported an Austrian commissioner, “you may rest assured we would not be here.”

Exhibitors had sold their goods at many previous World’s Fairs. The particular complication in Chicago seemed to be the sale of duplicate items by international vendors. The solution to the problem was to have their goods cancelled as exhibits and transferred to the government warehouse on the fairgrounds. There they were appraised, and an appropriate customs duty was paid. Duplicates of samples then could be placed in bond, sold at any time during the run of Exposition, and delivered at the close of the Fair.

Russian goods, once hiding under the covers at the 1893 World’s Fair, may perhaps still reside in the United States.

Side view of the Russian Pavilion in the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. [Image from Arnold, C. D.; Higinbotham, H. D. Official Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Press Chicago Photo-gravure Co., 1893.]

SOURCES

Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.

“Czar Land Treasure” Chicago Tribune Jul. 24, 1893, p. 8.

“Demands an Apology” Chicago Inter Ocean Jul. 22, 1893, p. 1.

“Discourteous Treatment of Foreign Exhibitors” Chicago Tribune Jul. 22, 1893, p. 12.

“Russia at the Exposition” World’s Columbian Exposition Illustrated July 1893, p. 126.

“Russia Gets Her Back Up” Rock Island (IL) Argus Jul. 21, 1893, p. 1.

“Russia’s Storm Over” Chicago Tribune Jul. 22, 1893, p. 2.

World’s Columbian Exposition 1893 Chicago, Catalogue of the Russian Section. Imperial Russian Commission, Ministry of Finances, 1893.

Cool