Halcyon Days in the Dream City

by Mrs. D. C. Taylor

Continued from Part 2

A long stretch of high stone wall above which clearly outlined against the blue of the summer sky, is seen a confused medly [sic] of queer tiled roofs, glimpses of latticed and casement windows, and above all a tall minaret, the turban like top holding up star and crescent. We pay the magic twenty-five cents and step into a curving narrow street, lined with dusky booths for the sale of numberless trinkets and mementoes of the Orient, but these have lost all charms for us; custom has staled them.[1]

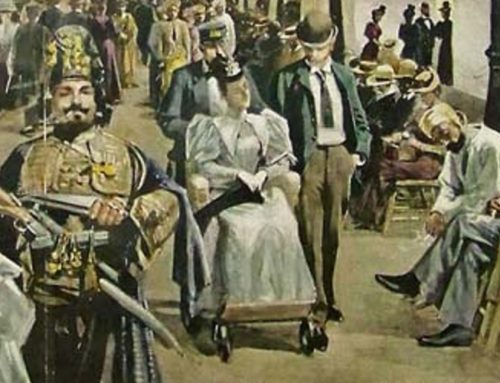

Cairo Street on the Midway Plaisance of the 1893 World’s Fair. [Image from Arnold, C. D.; Higinbotham, H. D. Official Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Press Chicago Photo-gravure Co., 1893.]

But the motley crowd, pushing, chattering, buying, selling! Ever and anon at the sound of a melodious cry in an unknown tongue, the crowd separates and the hideous head and long neck of a camel, slips through the hurrying mass like a ship through the waves of the sea, as easily, and as silently, for their broad padded feet make no noise upon the hard earth. The huge mountain passes, and again the cry is heard. Again the crowd parts, this time to let pass a tiny donkey with patient pathetic eyes bearing on his back a merry pair of boys.

Some denizens of the Street in Cairo. [Image from The Graphic History of the Fair. Graphic Co., 1894.]

We come now to the spot where the camels kneel upon sacks of hay, with great awkward bead and tinsel bedizened saddles upon their still more awkward backs. Beside each camel’s head stands a dark faced Arab in dingy white turban, with bare brown feet and legs showing beneath a very dirty, loose, wide sleeved caftan of blue cotton. Soon steps up a gay young couple evidently bride and groom, and after some parley and exchange of coin, the gentleman with the aid of the Arab hoists the lady upon the tall saddle, then the gentleman seats himself behind her with his arm about her waist, a strap from the back of the saddle is placed in his other hand, a similar strap from the front of the saddle is placed in the lady’s hand and then the Arab begins to punch the poor beast. Slowly the back end of the animal begins to rise, until both riders with great consternation depicted on their countenances, are obliged to lean back as far as possible to prevent being pitched off over the animal’s head. Then the experience is reversed, and both lean as far FORWARD as possible, meanwhile clinging frantically to the straps, while two or three little feminine squeals arise from the lady’s lips, but in a moment equilibrium is restored, the Arab walks off, the camel meekly follows, and the riders go jerking backwards and forwards, rising and falling at every step the lady’s bright eyes sparkling and white teeth showing, as she laughs in delight at the good natured admiring crowd. Soon they are swallowed up in the moving mass.

Then comes up two middle-aged ladies, prim and respectable in neat gray gowns, and carrying plethoric black silk bags in their black mittened fingers. They too, parley and pass coin with the Arab driver; they are both carefully seated on the saddle, the elevation begins, accompanied by frantic cries, and when the Arab essays to start the ship of the desert on its travels, one of the passengers clings tightly lo the Arab’s neck, the second clings as tightly to the waist of the first, and both beseech the driver to let them get down. In vain the crowd gives them encouraging cheers and laughing comments, but go they will not until the Arab gives the word of command, when again the groaning beast tilts down and up, and they land safely on the ground at last, having paid a dollar for the privilege of mounting and dismounting, and evidently thankful to get away at any price.

Exhausted with laughter we turn, and jostling and dodging our way along are soon attracted by the tinkling and twanging of stringed instruments, and pausing before the door from which the sounds issue, we perceive that it is the entrance to a Turkish theatre. Twenty-five cents and in we go. A long, room across one side of which runs a long, low stage, curtained and draped with rich Turkish rugs, and on a long, low divan is seated a queer looking band of men and women playing upon various queer looking instruments. In the center of the stage stands an olive skinned girl that looks as though she might weigh about two hundred pounds. A thin, white embroidered skirt falls in scant folds to her ankles; from belt to hem hang several long yellow satin ribbons, with gold coins suspended at the ends. This skirt hangs from directly under the abdomen, leaving it and the breast bare, excepting for a smooth-fitting silk gauze shirt, something like the “tights” worn by acrobats. Her great arms, bare save of bracelets, are thrust through the arm holes of a tiny little embroidered jacket that begins at the shoulder blades and ends several inches above the waist. Her abundant black hair, which is braided in two plaits, falls below the knees, and long strings of gold sequins are plaited in with the hair. In either hand she holds a pair of castanets which she clicks and beats

in time to her dance, and oh! that dance! She takes a few light steps to one side, pauses, strikes the castanets, then the same to the other side; advances a few steps, pauses, and causes her abdomen to rise and fall several times in exact time to the music, without moving a muscle in any other part of her body with incredible rapidity, at the same time holding head and feet perfectly rigid. That is all; the same movements over and over again in perfect time to the thrumming and tinkling, that is as little like music to our ears as her contortions are like dancing to our eyes.[2]

“Dancing Girls in the Egyptian Theatre on the Midway Plaisance” were featured on the cover of the August 10, 1893 cover of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly. Unlike the dancer described by Mrs. Taylor, this performer does not appear to weight two hundred pounds. [Image from private collection.]

Soon satisfied with this entertainment we turn our attention to the audience, which is constantly shifting. They are mostly staid, unemotional, middle aged people, with here and there a blooming young girl or dashing young man, but one and all gaze upon the strange uncanny dance that seeks to rouse the lower passions, but seemingly meets only cold surprise and contemptuous disapproval. No one lingers long. A little seems to go a great ways with these grave, good natured, sober-minded Americans. As we, too, pass out of the would be sensuous, Oriental atmosphere, we inwardly sing: “My Country ‘Tis of Thee.” Of thy myriad sacred homes, where purity and fidelity dwell with parents and children, of our innocent maidens that roam unfettered and safe through this “sweet land of liberty.”

Continued in Part 4

NOTES

[1] The official name of this concession, operated by the by the Egypt-Chicago Exposition Company, was “Street in Cairo.”

[2] Though she does not name the dancer performing this danse du ventre (aka the “hoochie coochie,” the “muscle dance,” or most commonly the “belly dance”), Mrs. Taylor appears to be describing the famous “Little Egypt” who performed in the Street in Cairo. The legend of “Little Egypt” has been researched and scrutinized by numerous popular and academic researchers. See, for example, Looking for Little Egypt (Intl Dance Discovery, 1995) by Donna Carlton, “Between Orientalism and Westernization: Belly Dance as a Transnational American Studies Case” by Perin Gurel (Comparative American Studies, 2016), and “Hoochie Coochie: The Lure of the Forbidden Belly Dance in Victorian America” by Michelle Harper (The Readex Blog, posted 5/04/2012). World’s Columbian Exposition historian Reid Badger cautions that “the reputation of the dancers on the Midway has probably exceeded the actual facts” (The Great American Fair: The World’s Columbian Exposition and American Culture. Nelson Hall, 1979, p. 161).

Leave A Comment