Personal accounts of trips to the 1893 World’s Fair offer candid and authentic insight into how visitors experienced the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Visitors famous and unknown have left behind memories of the Midway and whims of the White City on postcards and letters back home, in personal diaries preserved in archives, and through first-hand accounts published in newspapers. Some recollections appear in bound volumes published both professionally—Henry Adams’ The Education of Henry Adams (1909) and Clarence Day’s Life With Father (1935) are among the more notable titles—and privately.

Among the latter category is a collection of short accounts of visits to the Columbian Exposition written by Hattie Taylor of Kankakee, Illinois, and self-published in 1894 as Halcyon Days in the Dream City. She was the wife of prominent Kankakee businessman Daniel C. Taylor, who worked at the First National Bank there and had served as a representative in the Illinois state legislature. At the time of his death on October 15, 1894, newspaper reports described him as “one of the Democratic leaders of Eastern Illinois.” [“Prominent Democrat Dead” Rock Island (IL) Argus Oct. 15, 1894, p. 1.]

No more than a few weeks after her husband’s death, copies of Halcyon Days in the Dream City by Mrs. D. C. Taylor began to circulate. In their November 24, 1894, issue the Chicago Tribune announced that a copy had been received, and the Chicago Public Library recorded the title in their accession list for January 1 to April 1, 1895. The vanity press print run appears to have been quite small, as copies rarely come up for sale and only few are housed in archives (only four are listed in Worldcat, though three copies of her book reside in the collection of the Kankakee County Museum).

Halcyon Days in the Dream City by Mrs. D. C. Taylor

The handsome volume contains eighty-five pages of text bound in a pale blue cloth with its title stamped in gold on the cover. No publisher or printer is listed. Taylor’s memoir describes many separate visits to the fairgrounds. An early passage is identified as a “May morning,” (Opening Day of the Fair was May 1). Several pages later she chronicles visits in early June, and the final section describes a visit to the fairgrounds after the Exposition officially ended on October 30.

Halcyon Days divides Taylor’s reminiscence into two chapters, titled “Salve” and “The Plaisance.” We use her section headers to serialize the volume in seventeen parts following this Introduction. Within each part, we’ve divided the original text into paragraphs and added footnotes to assist readers.

Mrs. Taylor’s first-person plural narrative opens with “we first stepped through the turnstile” and closes with “we shall see thee no more” without naming her travel companions (though Bridget and John are mentioned in a passage about a visit to the Chinese Village). This casual mention of family or friends hints that Mrs. Taylor may have written and published this volume for the same audience.

As she and her companions meander along the Midway and circumnavigate the White City, Mrs. Taylor’s writing style ebbs and flows from colloquial to poetic. She is so deeply moved by the beauty of the grounds, architecture, illumination, and dense humanity that she describes the Exposition as “a foretaste of Heaven.”

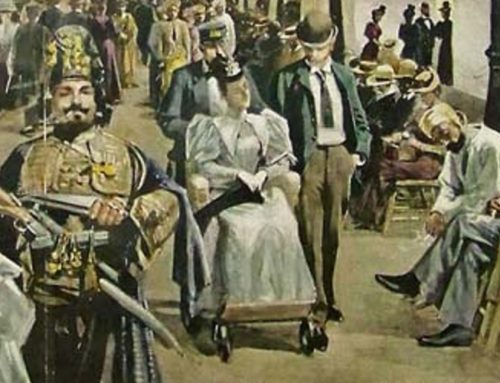

She also is quick to criticize attractions that she does not care for, and she is quite blunt in her assessment of the other cultures she encounters. Much of her memoir focuses on the Midway Plaisance and her visits to the international village concessions there. Like so many other American visitors, Mrs. Taylor experienced the various cultures on the Midway with an essentially voyeuristic approach. Moving between concessions, she comfortably adheres to the common notion of “Midway Types” on display for entertainment and for comparison against “civilized” societies. Most of the people she encounters and their traditions, garb, music, art, and products are judged through a western lens, yet sometimes sympathetically. She describes unfamiliar cultural artifacts as “strange looking” and unfamiliar names as “unpronounceable.” People dressed in non-Western garb are dismissed as “naked savages,” while others are simply deemed “cannibals,” “yellow faced,” or “dolls.”

As with many reprints from 1893, we caution readers to expect some language that by today’s standards is xenophobic and racist (e.g. referring to Native Americans as “savages”) and that conforms to gender norms of the late nineteenth century. By reprinting the original text, we in no way endorse such views. On the contrary, we hope that this perspective from America’s past can serve as a useful tool (for those with open minds) to examine how much our society has—or hasn’t—become more inclusive and appreciative of the diversity of people, cultures, and religions that make up our world.

Aside from some distasteful passages, perhaps we can accept Mrs. Taylor’s invitation—noted in her Introduction below—for “childish hearts” to take a happy trip with her through the 1893 World’s Fair. This rare record of a woman’s experiences at the 1893 World’s Fair is a historical treasure and fascinating travelogue.

[We thank Jack Klasey, whose article “Mrs. Taylor rode the ‘big wheel‘” appeared in the Feb. 15, 2018 issue of the Kankakee (IL) Daily Journal, for helpful discussion about Mrs. Taylor and her book.]

INTRODUCTION

To my little Grand Daughter, for whose sweet sake all children are dear to me, and the Kindergarten of Kankakee, this little book is dedicated, in the hope that it will make many childish hearts as happy as mine has been while writing it.

THE AUTHOR

Continued in Part 1

Leave A Comment