Continued here is a reprint of “CHICAGO AS CHICAGO IS. Impartial Observations of a Man Who Can See and Smell” from the May 29, 1892, issue of the New York Sun and alleged to be written by its editor, Charles Dana. Part 1 can be found here, and Part 2 can be found here.

CHICAGO AS CHICAGO IS

Impartial Observations of a Man Who Can See and Smell

(continued)

To sing the Chicago Fair, after this frank disclosure of their tastes, would be both an uneasy and ungracious office. Better leaver their celebration, therefore, to the bard who has appointed himself the Laureate of the Live Hog and taken up his residence in Chicago the better to discharge his lyric functions. None so well as Mr. Eugene Field can, with playful seriousness, do justice to a state of things as interesting to the sociologist as the arrested development of Australia’s fauna has always been to the lover of an unusual zoölogy.

Home of the “Laureate of the Live Hog,” Eugene Field, in the Buena Park neighborhood of Chicago. [Image from Leslie’s Weekly, Nov. 28, 1895.]

Borders horribly on the ridiculous

It is enough to say that the beauty of Chicago’s native women is almost entirely local and subjective. There is nothing in the world so reciprocally exact, that is to say, as the way Chicago criticism fits the charms of Chicago women, and the charms of Chicago women fit Chicago criticism. One cannot deny the plentiful abundance of curves and undulations, where, from an alimentary point of view, flesh and blood should curve and undulate. But desirable as the Chicago woman may seem in these particulars, the Chicago female eye is abnormally small, corresponding, almost grotesquely, with the eyes of its typical and emblematic quadruped. And the Chicago female nose is perilously like a pug or snub. Indeed, that snubness or pugness, which one hardly ever sees in New York, which, beginning in Philadelphia, is still more highly developed in Pittsburg, that pugness reaches its utmost degree in Chicago. Local authorities ascribe the marked retrocession of the organ to constant friction entailed by an almost incessant deposit of “blacks” on the nose and the resultant effort to remove them. Whatever may be the cause, the nasal tip-tiltedness in which Mr. Tennyson found delight, reaches in Chicago an extreme which borders horribly on the ridiculous.

It is another peculiarity of the Chicago female native that her lower jaw undergoes the most extraordinary spasms when she talks. There seem to be momentary dislocations of that important member, repaired only by a fierce muscular effort between each word. As may be conjectured, it is much more pleasing to hear her talk than to witness the parotid convulsions with which she punctuates her conversation.

There is not much more to observe about her, except the surprising abstinence from conventionality with which she accommodates herself to the Chicago idea of cable-car locomotion.

No car, open or shut, is ever sufficiently crowded to repel her from an entrance. She elbows and knees her way in with a gallantry unknown elsewhere, and does not hesitate, at times, to plump down on the lap of any convenient man rash enough to retain his seat. It must be admitted in her behalf, however, that she does all these unusual and un-Eastern things in an altogether artless and unaffected manner, such as characterizes a straw-ride in the prairie regions of the extreme West. There is nothing rude or wrong about it, only a touching adumbration of the simplicity which marks nature in her first stages and her most spontaneous moods.

Street car riders beware the Chicago woman who “elbows and knees her way in with a gallantry unknown elsewhere,” such as this one running along State Street north of the Palmer House Hotel. [Image from Wittemann, A. Views of Chicago. A. Wittemann, 1892.]

By the waters of the porcine Babylon

Among the immigrant women who swarm in Chicago, there is one conspicuous trait common to all of them. Whether they have come from Boston or Bangkok, San Francisco or St. Petersburg, London or Lubeck, the valley of the Mississippi or the banks of the Rhine, they are all animated by a single passion, a hopeless, heart-breaking desire to get away. You cannot sit at table in any Chicago hotel or boarding house without encountering some poor forlorn soul, high and dry and as desperately misplaced as if she were a Philadelphia Quakeress stranded amid the aborigines of the Solomon Islands.

Eastern women, so it would appear, can at a pinch stand everything Chicagoan except their own sex. The city is strewn with these dejected castaways of New England and New York origin, lamenting, like the starling of the Bastille, that they can’t get out. Especially is this true of spinsters, self-expatriated, each holding her nose by the waters of the porcine Babylon, while her eyes are turned forever to the East, as with perpetual hope the Mohammedan looks toward Mecca.

When, in fine, it is confessed that the woman of Chicago dares to revolt against all chromatic traditions in the matter of dress with a courage hardly credible in the East, everything has been said that any ordinary observer can say to stimulate general interest in her.

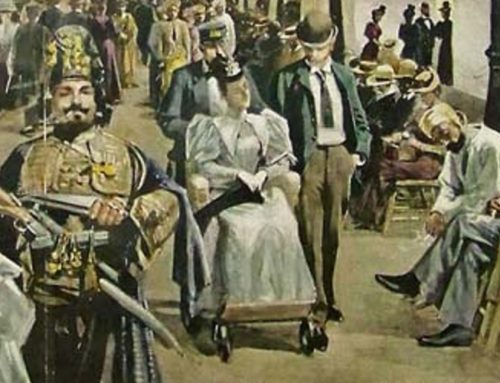

Two “dejected castaways” stroll on the fairgrounds along the south end of Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. [Image from a Strohmeyer & Wyman stereoscope card.]

Flagrant unveracities of the Fair

It is not unfair to the natives in control of this biggest of all big schemes to say that with characteristic American humor, they are already beginning to laugh out loud at their own effrontery. It is hard for them to discuss the flagrant unveracities of the Fair without an involuntary wink. In local conversation, “the opening of the show” has become an analogue to the Greek Kalends. They have indeed by this time reached such a stage of cynical candor as to beseech you when you listen to the glowing vaticinations of others to “play them with a copper.”

So long, of course as there remains the faintest chance of converting your credulity to their own personal profit, they agree to sustain the local legends. But the moment they find that you, too, are bent upon seeking advantages in the Fair, they hasten to tie straightforward with you and tell you the truth.

For there are moments even in the life of a World’s Fair “boomer” when he finds it worthwhile to be exact.

Progress on the fairgrounds sparked “glowing vaticinations” from World’s Fair boomers. This photograph shows the state of construction at the time this article appeared in print back East. [Image from Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume II. M. Juul & Co., 1894.]

Pillage the visitors

This cynical form of honesty assumes quaint shapes at times. For example, a Chicago Grand Columbian Fair Insurance Company has been organized. The purpose of this excellent corporation is to provide coffins, and, if preferred, interment in Chicago soil for the hundreds of calculable victims of that city’s profoundly insanitary conditions. The European visitor fated to die, according to an actuary-estimated percentage, of Chicago water or Chicago sewer gas is enabled to provide himself with all manner of conveniences for a trifling fee, The number of visitors who will thus speculate on their chances of surviving the Fair, is expected to be large and consequently profitable.

Another illustration of the excessive candor which at last begins to mark the enterprise, is the plan to farm out the pocket picking and other kindred privileges to practitioners of these arts whose responsibility and competence shall be beyond question. In other words, it is suggested that these gentlemen shall pay liberally for opportunity to pillage the visitors while evading the police, a merry game that seems, beyond doubt, full of promise for the players. Syndicates have been formed, or are in process of formation, for the protection and development of other “interests.” Among the germane enterprises under way is a “corner” in small change, contrived with a view of making the twenty-five-cent piece the unit of monetary measurement, just as San Francisco in the gold days, knew no coin smaller than the dime.

Would pick-pockets and con men “pillage the visitors while evading the police” at the 1893 World’s Fair? [Image from Harper’s Weekly, May 20, 1893.]

The moral and lacustrine mire on which she towers

It is not exaggerating the facts to say, in view of all this, that Chicago feels that this is a desperate, perhaps final, crisis in her history. The prospective existence of the next generation is involved. The fair over, she realizes that she may be avoided as the nidus of a pestilence, the swarming lair of an incomparable, an unparalleled, and a triumphant brigandage. She knows she will be regarded and shunned as the Abruzzi of the American continent, and she purposes to make her mammoth international “take off” conclusive and historical before the grass shall have a chance to grow in her streets and owls go mourning in her skyscrapers. She comprehends that the most energetic of predatory careers sooner or later reaches its end, and so, before she finally subsides into the moral and lacustrine mire on which she towers, she intends to play out the very greatest of all her “schemes” and the very softest of all her “snaps” for all that the adventurous game is worth.

Yes. When Chicago sits down to her international banquet on the lake shore, it will be found that, as in her favorite restaurant, “there ain’t no flies upon the victuals.”

“THE PICADOR.”

There ain’t no flies upon the Picador.

Leave A Comment