Continued here is a reprint of “CHICAGO AS CHICAGO IS. Impartial Observations of a Man Who Can See and Smell” from the May 29, 1892, issue of the New York Sun and alleged to be written by its editor, Charles Dana. Part 1 can be found here.

CHICAGO AS CHICAGO IS

Impartial Observations of a Man Who Can See and Smell

(continued)

In a week one gets sufficiently acquainted with the metropolis of Misrepresentation to realize the astounding disappointment which it will inflict upon the credulous Europeans who intend to visit it during the next two years.

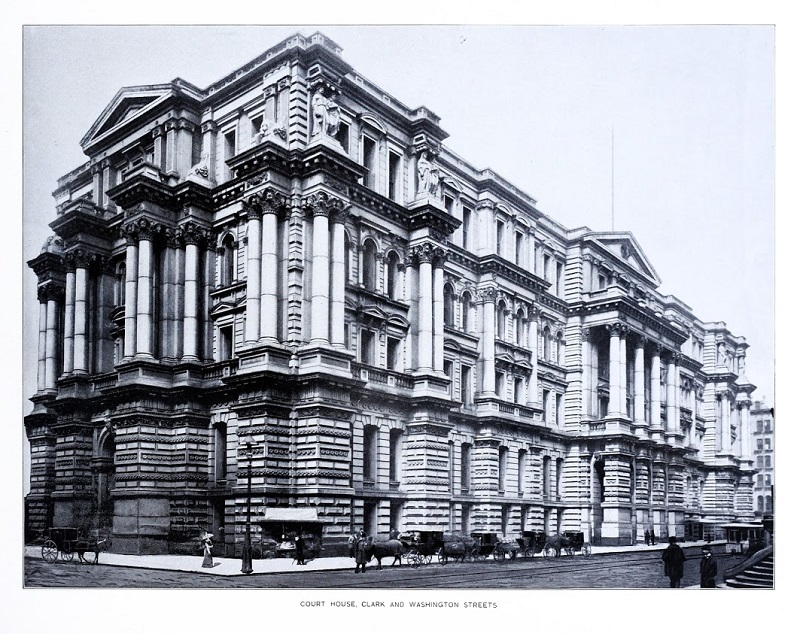

The first and most repulsive characteristic of Chicago is what is known as its business centre. This centre is a district, by no means of extensive area, which contains the Court House, the Post Office, the Western Union building, and the Board of Trade as its fourfold focus. Some years ago the “business” population displayed a tendency to spread out, as they call it in Chicago. The area of office room began to widen and the landowners of the “centre” district contemplated with alarm the possibility of having to share their tenantry with an ever-increasing horde of landlords. It was to obviate this that the owners of the district devised the “sky-scraper” order of architecture, which is the principal boast as it is the principal deformity of Chicago.

At the center of the “first and most repulsive characteristic of Chicago” stands her Court House. [Image from Rand, McNally & Co.’s Pictorial Chicago and Illustrated World’s Columbian Exposition. Rand McNally & Co., 1893.]

Affright and disgust the critical observer

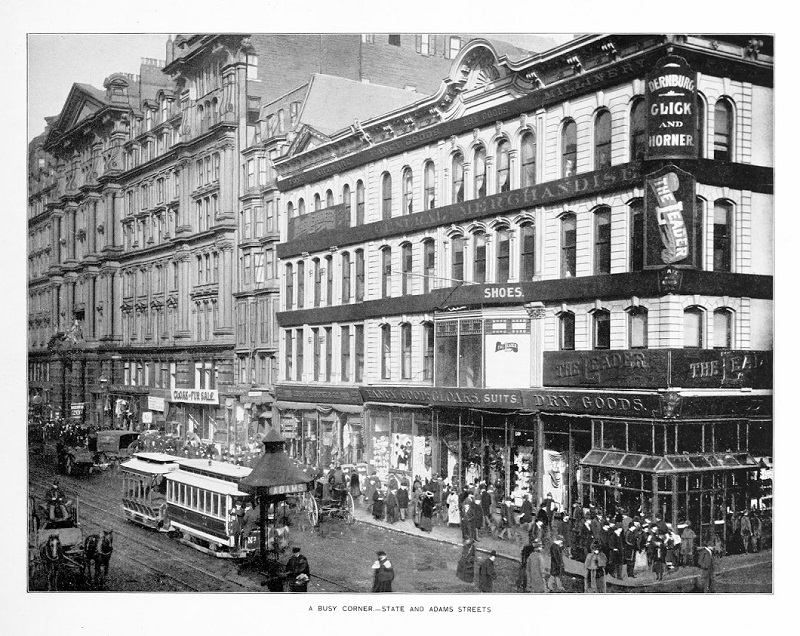

These monstrous office structures are hardly any of them less than twelve stories in height. A good many of them are of twenty-four story altitude. A few contain nearly thirty tiers of offices. All their exteriors are in general expression alike. They differ only in details, “trimmings” they call them in Chicago. They are all built of stone, principally the dull, dark gray stone excavated by convicts out of the quarries of Joliet. Some pretend to a finicking originality. The façades differ in design. In one there is an abundance of metal work, in another none at all. There is a single characteristic, however, common to all of them, the extraordinary quantity of small jail windows which pierce their walls.

A great many of them are built on a first floor, a rez de chaussée of dwarfed and dumpy arches. In perhaps twenty instances all there is of each arch is the arc. The columns or abutments are altogether lacking, and the chord of the arch is supplied by the threshold. Sometimes there are short, rudimentary columns, terrible squat things that affright and disgust the critical observer. It looks, in all such cases, as if the weight of the pile superimposed upon these colonnades had driven the columns so deep into the soft, swampy soil of the city, that nothing but the arches themselves remained visible.

Nor it this impression of settling altogether unfounded. Chicago stands upon a quicksand. At a well-defined, universal depth there is a subterranean inflow of the lake. Beneath that lacustrine space is more or less solid ground, but hardly any of the buildings are erected on foundations running clear through to this solid, substantial bottom. Most of the top-heavy structures are founded on the quicksand, into the lower strata of which the lake flow percolates.

Hence it is that several of the larger buildings throb with the pulses of the machinery they contain.

Buildings that “affright and disgust the critical observer” along State and Adams Streets in Chicago. [Image from Rand, McNally & Co.’s Pictorial Chicago and Illustrated World’s Columbian Exposition. Rand McNally & Co., 1893.]

Looks exactly like petrified smoke

Take, for example, the vaunted Auditorium, that curious combination of a hotel, a theatre and a public hall. It is an enormous collection of rectangles. All its lines are the lines of correlated parallelograms. Its model was evidently a soap box. For a tower it has a long macaroni box set on end. On the top of the macaroni box is its cap, a gray cube, that is beyond doubt a match box. It is built of a dark, sombre stone, which looks exactly like petrified smoke. You find it easy to imagine after examining it that Chicago genius has found a way to convert her bituminous fumes into building material.

Its ground floor has the appearance of settling fast into the quicksand on which it stands. Perhaps it is so settling. [We’ll give you this one, Charlie—Ed.] At all events, it seems to be descending into the subterraneous ooze.

Sitting in the great hall of the building when its fifteen or sixteen various engines are at work, you are seized with consternation. There is a terrifying roll right and left, an incessant pitch fore and aft. Sudden chills and thrills of the overworked, under-founded structure are distinctly perceptible.

Even your Chicago cicerone confesses the existence of these alarming phenomena, but he says that they are not ominous of danger, that they indicate no structural debility. “It is,” says he, “one of the peculiarities of the building.” You find, afterwards, that the Auditorium does not monopolize this peculiarity. There are other less vaunted buildings which have the same spasms and shudderings when their machinery works hard and fast.

Those Chicago geniuses who “found a way to convert her bituminous fumes into building material” for the Auditorium are, of course, Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan. [Image from Artistic Guide to Chicago and the World’s Columbian Exposition. R.S. Peale, 1891.]

Adapting her houses to giants

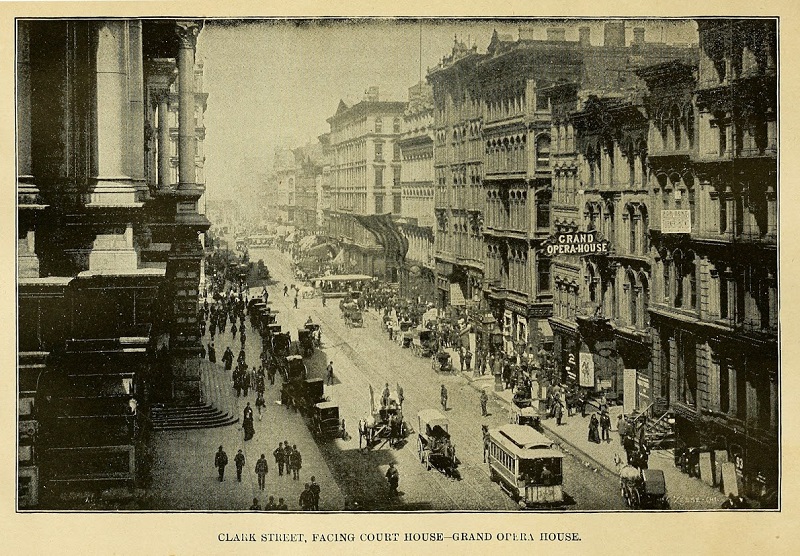

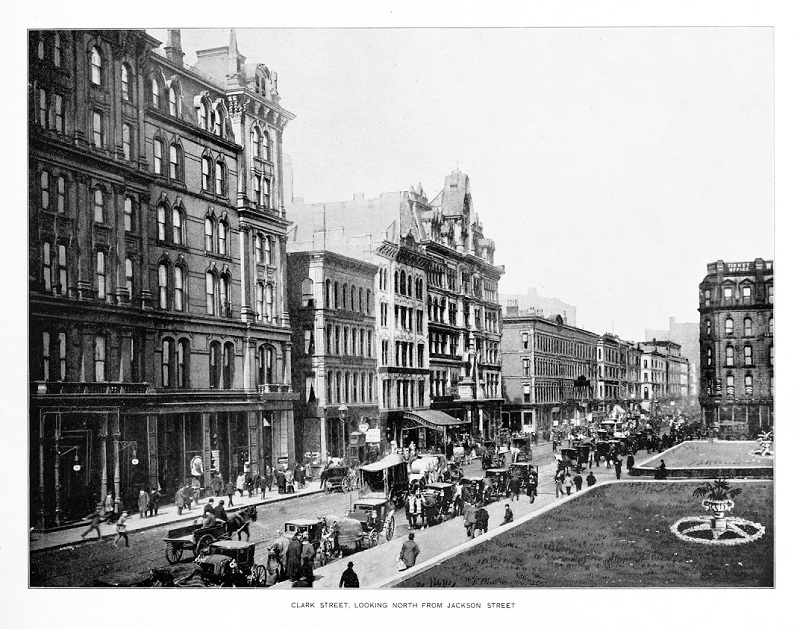

The enormous height of the structures in the “business centre” has not been matched by a proportionate widening of the streets. They are of normal width. As a natural consequence, the towering office buildings on each side practically alternate them. The sidewalks look like thin ribbons of granite, the wagon ways like ordinary foot paths. The dwarfing influence of the loftiness of the buildings is apparent and effective otherwise. People look like midgets. You lose all criteria of size. Your rule of comparative measurement is withheld from you. A man walking past a twenty-story structure looks half as big as a man walking past a building with only ten tiers of windows. The man who walks past a building of five is, after all, your normal unit. In other words, by adapting her houses to giants in her business centre Chicago has transformed her population into a horde of pigmies.

A scene showing the “dwarfing influence of the loftiness of the buildings” along Clark Street, with the Court house (left) and the Grand Opera House (right). [Image from Artistic Guide to Chicago and the World’s Columbian Exposition. R.S. Peale, 1891.]

In this sinister twilight

It is in these streets, these deep gutters between towering man-cotes, that one sees and considers the people of Chicago. So narrow are the thoroughfares, so high the buildings, that they are sunlit and cheerful only when it is the hour of high noon and the solar beam drops perpendicularly. At other times they are steeped in chill and suffocating shadow. Most of the time they are roofed by the canopy of smoke, which descends so low that it rests upon the buildings as upon abutments.

Perhaps it is in this sinister twilight which gives to the men and women who swarm among these warrens their haggard complexions, their sad and tired air. Like the beings so terribly imagined by Edgar Poe, you hear them laugh, you never see them smile. It is the very thick and fury of the struggle for Life. All of them, men and women, equally look desperate. They show each other none of the small considerations of politeness. They elbow and squeeze and crowd each other, looking neither to the right nor to the left. They have no time to get out of each other’s way or to apologize for their incessant infractions of the code of pedestrian ethics.

It is a modified sauve qui peut, a merciless and general panic born of a desperate fear either of being overreached, or of missing an opportunity as the penalty of an instant’s delay.

The hurrying and the jostling are evenly divided by the two sexes. Women crowd men, men elbow women, and an instinct of self-preservation serves as the universal excuse.

“Incessant infractions of the code of pedestrian ethics” along State Street in Chicago. [Image from Pierce, James Wilson Photographic History of the World’s Fair and Sketch of the City of Chicago: A Guide to the World’s Fair and Chicago. Lennox Publishing Co., 1893.]

Open-air hucksterings

When two men meet, as they do very frequently, to traffic on the sidewalk, the conversation is incredibly laconic. Each wants to sell the other something. Neither wants to buy. It usually ends in an “even swap,” out of which no perceptible profit comes to either.

It is worth while to listen to some of these open-air hucksterings. The reciprocal trade is strictly in potentialities. They are trying to “stick” each other not with palpable and material commodities, but with schemes and options and big chances.

You begin by laughing outright at the nature of the wares thus hawked in open market. You end by wondering why Hungry Joe and Kid Miller never thought of entertaining in a Chicago Board of Trade for “puts” and “calls” in the green goods line.

A “great scheme” exchanged for a “big snap”—an “option” turned over as payment in full for a “privilege”; such are the principal business transactions which are conceived and executed in the pigeonholes, or, shall I say, the vulture roosts of the skyscraper of Chicago!

[One paragraph omitted—Ed.]

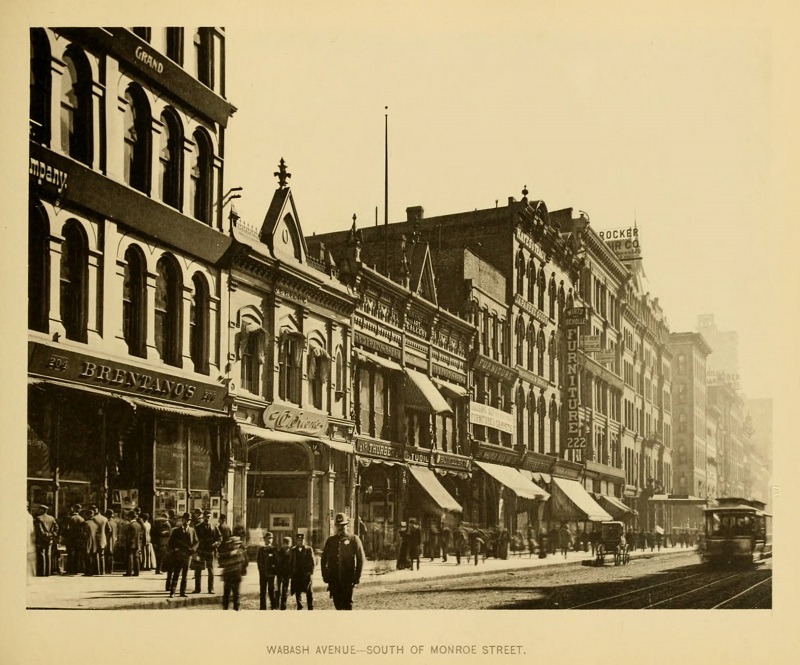

“Open-air hucksterings” along Wabash Avenue, south of Monroe Street. [Image from Wittemann, A. Views of Chicago. A. Wittemann, 1892.]

Unceasingly devouring one another

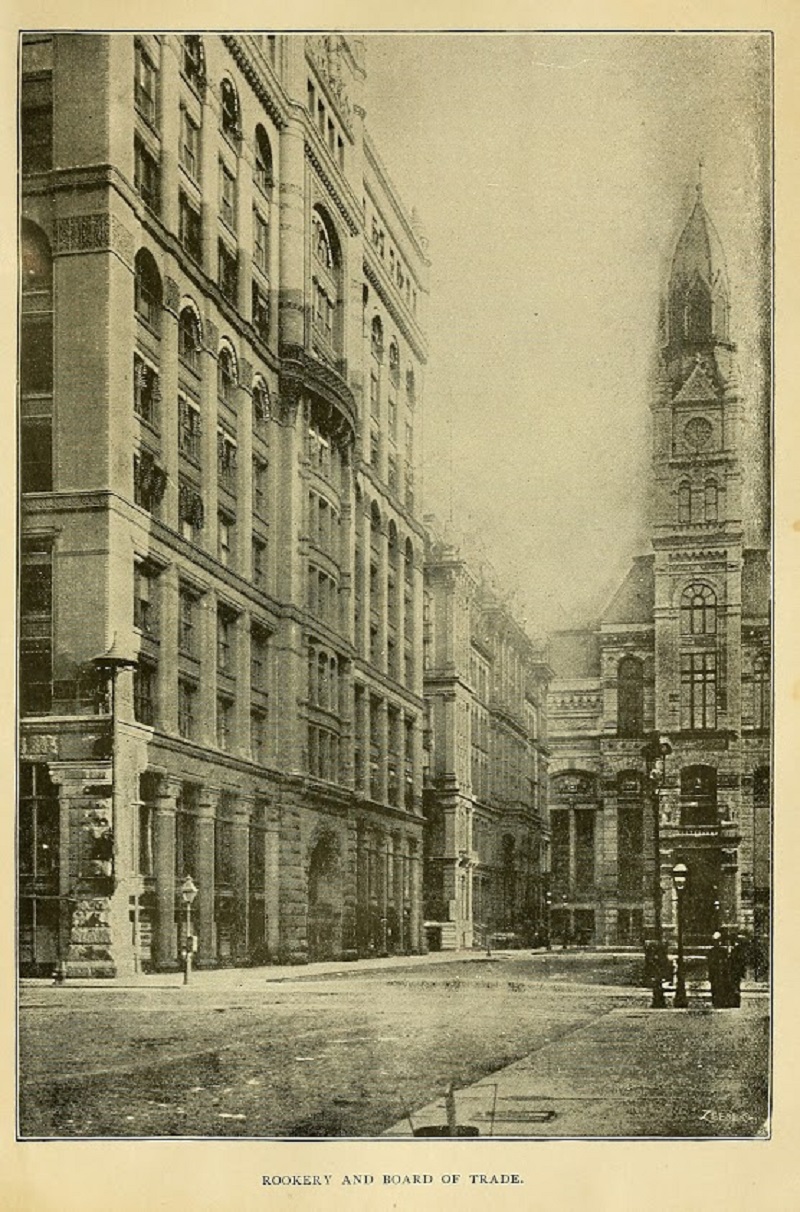

He would have been reconciled to Mr. Oliphant’s project had he lived in Chicago. A brief residence in the Rookery—better named the “Hawkery”—would have contradicted many hoary axions, among them the Scottish proverb that “Corbies na pick oot corbies’ ’een.” He would have seen a preposterous community, if not exactly a happy one—of commercial freebooters buccaneering on the cooperative plan and unceasingly devouring one another. He would have been edified by the discovery that there is after all value received by both parties in the transfer of protested checks for “wildcat stocks” and a vital usufruct in the swapping of “lead-pipe cinches.”

An experienced authority says of Chicago commerce: “You enter our Board of Trade on a handshake, and you work it for all it’s worth on the flim-flam racket.”

This is, equally, the jargon of business, in Chicago, and of the art and practice of bunco in New York; from which one gathers an impression, which may be only moderately correct after all, that what passes for bunco in New York would be regarded as nothing worse than business in Chicago.

“Commercial freebooters buccaneering” along LaSalle Street, with Burnham and Root’s Rockery (left) and the old Chicago Board of Trade (right). [Image from Artistic Guide to Chicago and the World’s Columbian Exposition. R.S. Peale, 1891.]

Practitioners of bunco

Extremists, in view of this fact, may go so far as to asperse all Chicago business men as mere practitioners of bunco, but there is no doubt that such a deduction apparently amounts to extravagance of statement. There are, beyond question, men who carry on business in Chicago who would resent an invitation to practice bunco in New York.

Under these conditions, dealing in subaqueous real estate on the part of a Chicago business man belongs to legitimate trade, instead of coming under those previsions of the New York Penal Code which relate to swindling and false pretenses. The Chicago alethometer is not so delicate or so sensitive as the New York instrument, a fact, doubtless, due to differences in climate. At the point at which in New York it registers Fraud, in Chicago it simply indicates Enthusiasm or Hyperbole.

The tendency of Chicago business men to market their imaginary wares upon the sidewalk probably explains the disagreeable congestions which make it hard to pass unruffled through Lasalle Street, or Dearborn Street, or North Clark Street, or any other thoroughfare in which one is perpetually recording quotations of “big schemes,” of “great snaps,” or “options,” or “privileges,” or other commodities popular upon the Chicago Rialto. Real corn, and wheat, and leather, and groceries speak for themselves. A vast deal of explanation naturally embellishes and enhances that traffic in pure myths which, in Chicago, takes the place of actual commercial interchange.

The “disagreeable congestions which make it hard to pass unruffled” through Clark Street Clark Street, north from Jackson Street. [Rand, McNally & Co.’s Pictorial Chicago and Illustrated World’s Columbian Exposition. Rand McNally & Co., 1893.]

Professional gents

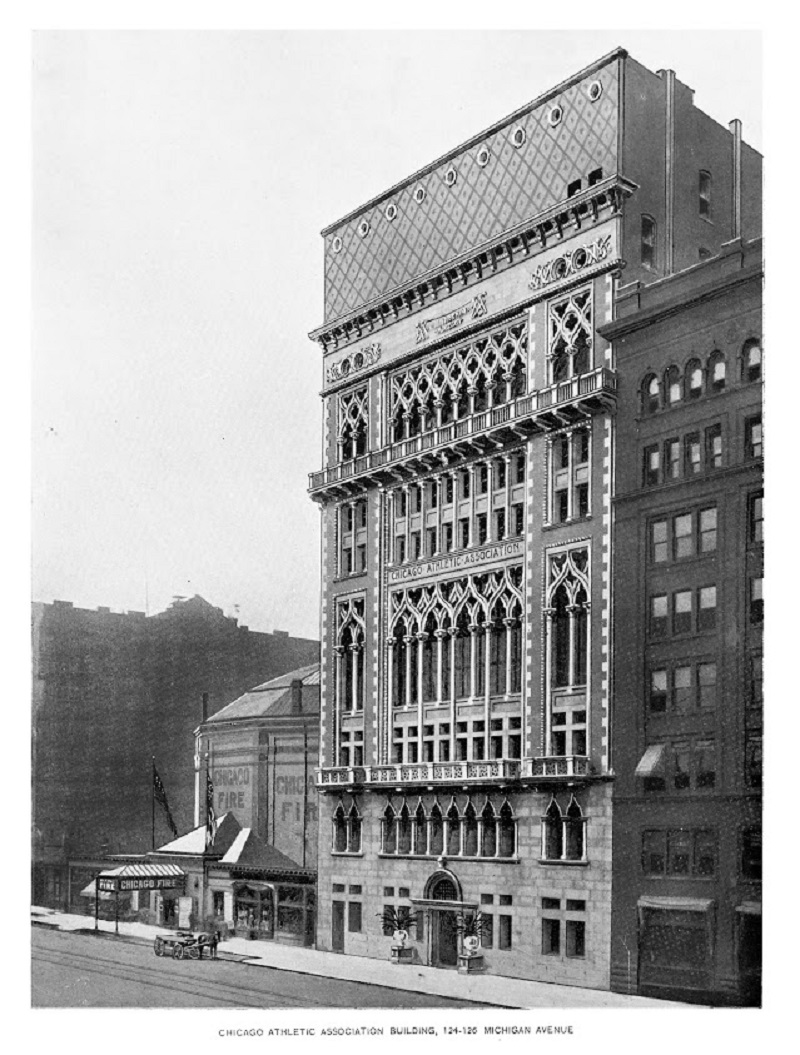

But all the male inhabitants of Chicago are not necessarily business men or expert practitioners of bunco. There are numbers of them who are what may be called, in default of a more distinctly definite phrase, “professional gents.” Indeed, Chicago may boast among its other vaunts of being the paradise of the gent. There you may observe him in all his stages of development, from the budding gentling in his first pair of creased trousers to the consummate flower of genthood, gold chain, diamond studs, patent-leather shoes, cigarette holder, satisfied smirk, bad grammar, and all.

There is, probably, no other community in the world which is so inclined to gent-ness as this city of skyscrapers.

It would be interesting to learn the secret of the correlation between the local layout, as it is picturesquely termed, and the local tendency to gentness. No matter what that secret may be, the consequence is too obvious to disregard. The shams of the local architecture and the local commerce are exactly paralleled in the utter and splendacious falsity and bad form of the local clothing and the local manners.

Even Chicago business men and Chicago gents have to eat and drink. The twin appetites of hunger and thirst they satisfy after their kind with all the noise and ostentation in which every citizen of Chicago seems to feel a voluptuous delight.

Gentlemen of “utter and splendacious falsity and bad form” gathered in clubs such as the Chicago Athletic Association on Michigan Avenue. [Image from Rand, McNally & Co.’s Pictorial Chicago and Illustrated World’s Columbian Exposition. Rand McNally & Co., 1893.]

An amazingly garish parcel of young men

For example, the beau monde of Chicago, that affluent and artless class to be able to satirize which upon the spot seems to be the only influence that prolongs the residence of Mr. Eugene Field within its neighborhood: the beau monde celebrates a night at the theatre in a manner distinctly different from that in which an opera party in New York winds up at Delmonico’s. The beau monde, an amazingly garish parcel of young men in swallowtails and satin puffs, abetted by a still more garish parcel of young women in bright silks and crapes, descends after the theatre shrilly and screechily into a spacious whitewashed cellar, which calls itself the Boston oyster house. The timid traveler fancies for a moment that it is a magnificent imitation of the vault in which the late and deeply lamented Oliver Hitchcock used to serve the printers and journalists of New York with his justly celebrated coffee and doughnuts. [Hitchcock was described in A Boy’s Fortune by Horatio Alger—Ed.] But he soon learns that the Boston oyster house is nothing less than a Chicago improvement on the Brunswick or Sherry’s.

It is lit up by fizzing arc lights in ground glass globes. The walls are hung with huge cardboard escutcheons, on which are set forth both the virtues and the prices of the delicacies in local vogue. These consist principally of lobsters and clams, cooked and garnished after modes popularly supposed in Chicago to reflect the loftiest gastronomic triumphs of New York. It is only fair to say that no New Yorker would ever dream of insulting his digestive functions with the mysterious combinations for which he is legendarily held responsible in Chicago.

Great quantities of Bass’s ale are absorbed in these post-theatrical revels and very little champagne. The local beer is so execrable that even the local dipsomaniac avoids it. Minced lobster, hashed lobster, lobster in a dozen new forms, flanked by bottles of Dog’s Head or White Label, makes up the jovial feast. The noise is deafening. Indeed, the art of conversation in Chicago is evidently based upon the system of phonetic signals used by locomotive engineers in talking with one another. A male Chicagoan makes no pretense of ever trying to drown it.

It is due, however, to the waiters in the Boston oyster house to confess that they contribute real and desperate efforts to talk down the ladies into desirable silence. They wear white jackets, these waiters do, just like the late Mr. Hitchcock’s cake-and-coffee-bearing waiters, and they deport themselves with an easy grace and a charming familiarity hardly to be distinguished from the désinvolture of their customers. If it were not for their white jackets, there would be moments when the untutored and inexperienced traveler would be apt to mistake the waiters for the beau monde and the beau monde for the waiters.

But, then, it is only fair to suppose that the waiters of the Boston oyster house really come from Boston, whereas it would be all but impossible to declare with certainty the origin of the Chicago beau monde who patronize the Boston oyster house and mix familiarly with its waiters.

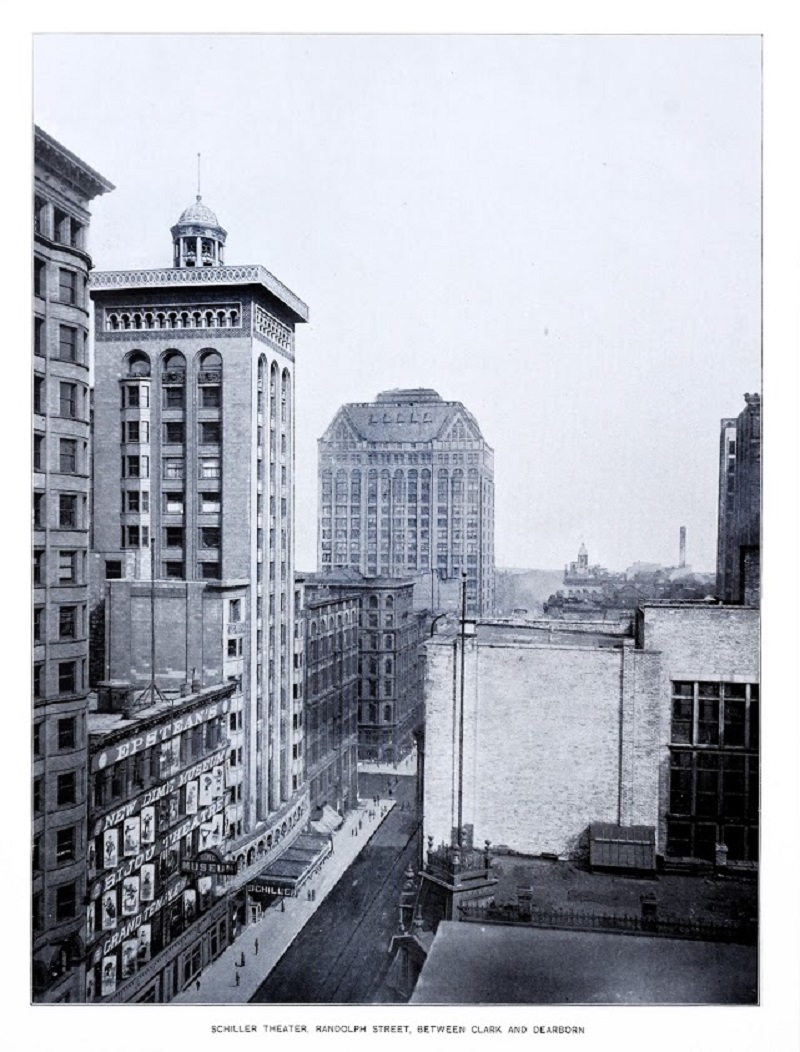

An “amazingly garish parcel of young men in swallowtails and satin puffs” would gather in places such as the Schiller Theater on Randolph Street. [Image from Rand, McNally & Co.’s Pictorial Chicago and Illustrated World’s Columbian Exposition. Rand McNally & Co., 1893.]

“There ain’t no flies on our victuals.”

There are other restaurants in Chicago, of course. They have various claims upon local favor. Their claims upon foreign patronage, however, cannot be easily protested. One of the most popular of these extols neither its kitchen nor its wines, but defiantly proclaims the fact that “There are no flies upon our victuals.” This, it seems, is not a mere picturesque and racy metaphor, but the declaration of a singular and undeniable entomological truism. You may vainly demand such a dinner as would satisfy a New York man of moderate appetite. But, on the other hand, you cannot avoid noticing a delightful absence of the blue bottles which swarm in noisy millions in all other rival established eating houses in Chicago.

Albeit, the popular impression is that the proprietor would have more accurately stated his case had he announced that “there ain’t no flies on our victuals.” Still, Chicago is, on the whole, proud of what he has accomplished, and when the traffic in “options,” or “big things,” or “great schemes” is brisk, dines liberally, if barbarically, at his table.

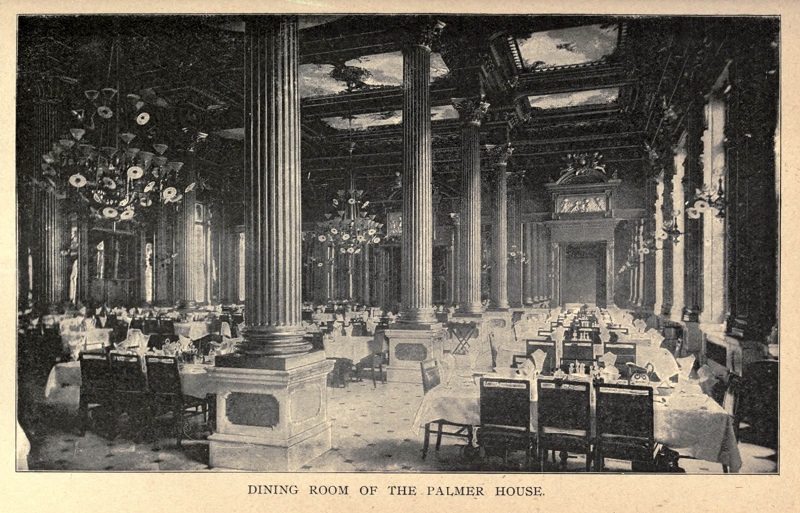

Chicagoans dined “liberally, if barbarically” at restaurants such as that of the Palmer House Hotel. [Image from Pierce, James Wilson Photographic History of the World’s Fair and Sketch of the City of Chicago: A Guide to the World’s Fair and Chicago. Lennox Publishing Co., 1893.]

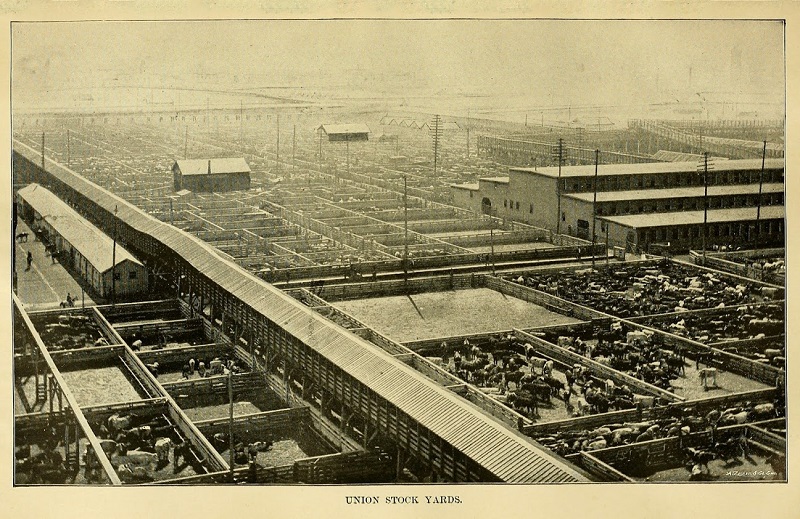

Sanguine horrors of the Hog Killeries

Indeed, it is hard to say which of the twin local entertainment is the more urgently commended to the visitor, a day amid the sanguine horrors of the Hog Killeries or a dinner in the salon where “there ain’t no flies on our victuals.”

Not that the “business men,” or the “gents,” or the ladies of Chicago are at all disposed to underestimate the joys of an hour profitably spent among the crimson streams of their slaughter-houses, that memorable hour which is the very climax of a day’s pleasure in Chicago’s world-famous stockyards.

The weird and, to the stranger, inexplicable delight which a Chicago man or woman finds in making the acquaintance of a hog, only to follow him gloatingly through all his rapid transit from the pen to the sausage mill and the blood-tub is happily a local sentiment, almost impossible of acquisition by an alien.

Visiting ladies, unaware of the precise nature of the porcine tragedy in which so many of the native fair rejoice, have been known to faint at sight of the penultimate atrocities. Strong men, unaccustomed to take their pleasure in shambles, have rushed headlong and sickened from the gory scene. But the beau monde of Chicago observes the slaughter and the quartering of pigs with a lofty, critical rapture not at all dissimilar to the joy with which Andalusians regard the finish of a bull-fight.

What is less intelligible is the resentment with which they notice and deprecate any failure to appreciate their favorite diversion on the part of their nauseated visitors.

Continued in Part 3 …

Strong Chicago men “rushed headlong and sickened from the gory scene” at the Union Stock Yards. [Image from Artistic Guide to Chicago and the World’s Columbian Exposition. R.S. Peale, 1891.]

Leave A Comment