The 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago shines on the big screen, if only for a few minutes.

The Current War (2017, released 2019) tells the story of the rancorous rivalry between inventor Thomas Edison (Benedict Cumberbatch), who adamantly championed direct current (DC) technologies to electrify and illuminate American cities, and George Westinghouse (Michael Shannon), who banked on alternating current (AC). The legendary “war of the currents” has these titans of the electrical industry setting their sights on powering the Columbian Exposition.

Thomas Edison showing off his new incandescent light bulb opens The Current War.

—— SPOILER ALERT ——

The Current War opens with Edison’s efforts to bring DC-powered electric lighting to part of Manhattan, a difficult relationship with his financial backer J. P. Morgan (Matthew Macfadyen), and the devastating loss of his first wife, Mary Stilwell (Tuppence Middleton). Pittsburgh industrialist Westinghouse bets his business empire on AC generators and the new polyphase system developed by genius inventor Nikola Tesla (Nicholas Hoult).

When Westinghouse invites the wizard of Menlo Park to meet with him in his Pittsburgh castle, Edison snubs him at the last possible second, ordering his train to continue past the station as Westinghouse watches him pass in disbelief and furor. This incendiary act, which lights the fuse of the war of the currents, is one of several scenes invented by the script writer for dramatic effect.

Setting the stage for the greatest battle between the industrial giants is an 1890 newspaper headline announcing Chicago’s winning the bid to host the upcoming World’s Columbian Exposition. The drama focuses on the quest of Edison and Westinghouse to win the contract to electrify the Fair. Edison recognizes that the White City is ephemeral and will come down after only six months. Samuel Insull (Tom Holland), his assistant and the president of the Chicago Edison company, reminds him of the importance of “Chicago as a symbol: A City of Light.”

Flying over the Columbian Exposition fairgrounds in 1892, as shown in the trailer for The Current War.

The first view of the Columbian Exposition comes as we enter along the train tracks behind the Terminal Station and then fly over the fairgrounds during construction in 1892. The scene is fascinating, but very short. Some of this brief shot was included in a trailer released in the summer of 2019, and we noted both the veracity and some interesting departures in the fairground built by the film’s digital graphics department.

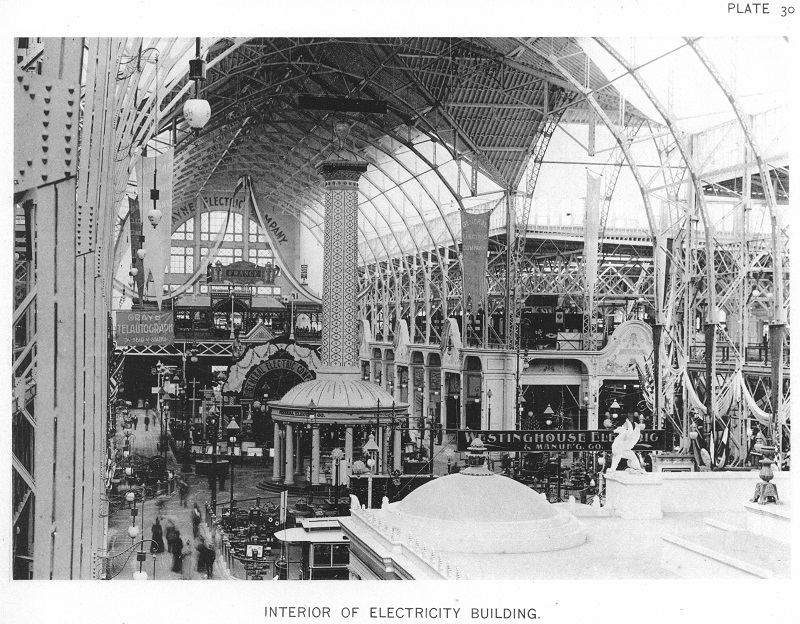

We see a drawing of Edison’s proposed electrical exhibit at the Fair: his Tower of Light. Later in the film is an excruciatingly brief shot of the interior of the Electricity Building, showing the displays of both Westinghouse and rival General Electric, with the Edison’s Tower of Light, in the frame. World’s Fair enthusiasts who are familiar with black-and-white photographs of this spectacular display of electrical lighting miss the chance to experience the scene that amazed visitors in 1893: seeing an eighty-two-foot column burst with the illumination of 5000 light bulbs.

The exhibits of Westinghouse (foreground) and General Electric and the Edison Tower of Light (background) in the Electricity Building. [Image from Arnold, C. D.; Higinbotham, H. D. Official Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Press Chicago Photo-gravure Co., 1893.]

This publicity photo, showing Nikola Tesla at the 1893 World’s Fair, depicts a scene not present in the final cut of the film.

A brief shot shows workers installing light bulbs on the grounds of the Exposition precedes what was anticipated as the scene potentially offering the greatest visual drama: Opening Day Night. Thousands of fairgoers excitedly walk along the Grand Basin towards the Administration Building. Moving the Opening Ceremony to nighttime offered filmmakers the opportunity to show what had to have been one of the most marvelous experiences of the fair: watching the thousands of light bulbs and giant search lights flicker on. Tension builds in the scene as President Grover Cleveland approaches the table to press the button that will bring the machinery to life.

President Grover Cleveland about to bring the machinery to life. In fact, the Opening Ceremonies took place during the day, not at night.

Accompanied by the pulsing music of Max Richter’s “Autumn 3,” the scene jumps between the impending illumination of the White City and the horrific electrocution of convicted killer William Kemmler in Buffalo, New York, through the “humane” device of an electric chair. The screen splits into three images showing a sequence of images of the fairgrounds—the Administration Building, gondolas in the Grand Basin, the Ferris Wheel—already lighted … and then it is over.

The rushed, low-wattage scene is a disappointment for those expecting to see the drama of the grand illumination. Furthermore, the juxtaposed electric-chair execution actually had occurred three years earlier and in Auburn, New York. With such disregard for historical facts, the film’s story burns out like a cheap filament.

Oh, and there is an elephant walking around the fairgrounds that night. Perhaps this was Lily from Hagenbeck’s Arena? Or a nod to the rumors of Edison having electrocuted an elephant at Cony Island later in life (He didn’t.)?

For a few splendid seconds, the film provides a gorgeous still shot of the Grand Basin from the view atop the Peristyle, showing the golden Statue of the Republic glowing softly in the electric lighting and the exhibition palaces framed in light bulbs. The brilliant scene leaves World’s Fair fans wanting more.

Westinghouse and Edison meet and converse at the 1893 World’s Fair, an encounter invented for The Current War.

Having realized that Westinghouse has won the “War of the Currents,” Edison grumbles: “Let the man have his Fair and waterfall.” The action returns to the fairgrounds for an invented scene in which Thomas Edison meets with George Westinghouse. (In fact, the two electrical industry rivals never met.) Their conversation occurs inside of an unidentified exhibition hall having Beaux Arts design and decoration. Next to them, a Japanese woman sits inside of a fenced exhibit area showing her calligraphy work. It is an oddly unimpressive choice, given all of the actual wonders of the Fair that could have served as a backdrop … the Ice Railway, the Golden Door, the windmill exhibit … even a Liberty Bell made of oranges!

Edison mentions that he had just visited the Midway Plaisance to see Eadweard Muybridge’s zoopraxiscope exhibit and a performance by the dancer “Little Egypt.” Documents of Edison’s brief time on the fairgrounds do not indicate he ever ventured onto the Midway.

A final invented scene has Nikola Tesla standing in front of a cloth painting of a waterfall, advocating the promise of generating bountiful electricity from water turbines. The film then closes with Edison standing beneath Niagara Fall, capturing not its hydroelectric power but its majestic image on celluloid.

Columbian Exposition enthusiasts may find interest in this background story about the technology that electrified the White City. Those completely unfamiliar with the history of war of the currents, however, likely will leave the theater confused.

Which electrical system will light up the United States? Westinghouse and Tesla’s AC system, or Edison and Insull’s DC?

As the lights went out on the 1893 World’s Fair, inventions that captured and projected flickering images ignited the American cinema industry. A small building on the Midway Plaisance offered a glimpse of what was to come to those few World’s Fair visitors who found their way inside Muybridge’s Zoopraxographical Hall. The 1893 World’s Fair, though profusely documented in text and photography, narrowly missed her chance to be preserved in moving pictures. During the past century and a quarter, only a few video works have even attempted to recreate scenes of the Exposition. The Great Ziegfeld (1936), Wabash Avenue (1950), “The Longest Beard in the World” episode of Death Valley Days (1956), and “The World’s Columbian Exposition” of Timeless (2017) have depicted modest and mostly inauthentic representations of the White City and Midway Plaisance.

The Current War could have illuminated the great American fair, offering viewers a sense of the awe that visitors in 1893 experienced as they first entered Jackson Park by boat or train, stood beneath the majestic Administration Building dome, rose above the Midway on a Ferris Wheel ride, or watched the Dream City sparkle at dusk. Instead, we were left with only brief flashes of her white palaces and wondrous attractions. Let’s hope that a DVD release offers additional footage. If not, perhaps the gates of the Fair will re-open in the upcoming mini-series of The Devil in the White City.

Leave A Comment