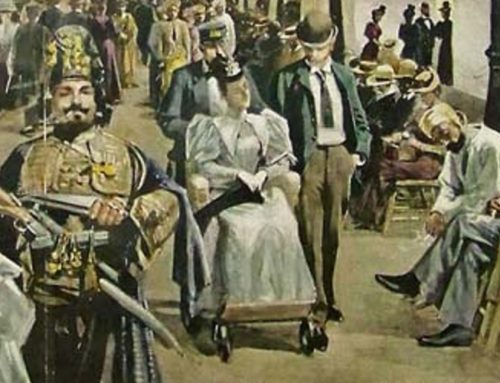

The Fourth of July was one of the great “Special Days” of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The passage below comes from “The World’s College of Democracy” by John Brisben Walker, published in the September 1893 issue of The Cosmopolitan, of which he was the owner and editor. Of all the wonders of the Fair around him, Walker boasts most about the conduct of the visitors on Independence Day.

It was my good fortune to be present on the Fourth of July, when the number of people on the grounds exceeded three hundred and five thousand. It was most interesting to study the faces, to note the looks of appreciation, to hear the exclamations of admiration, to listen to comment which was intelligent even when the garb was homely. I walked through many miles of avenues on that day: everywhere unmistakable signs of enjoyment, everywhere the comment of intelligent appreciation, and above all, everywhere the utmost good-nature. That, to my mind, was the most marvellous exhibition of all, that in a crowd containing more than three hundred thousand souls there was not, so far as I was able to see, and I carefully searched for it, one ill-tempered face, one drunken man. What a change has come over our civilization in the past twenty-five years! Such a crowd, anywhere in the United States, before the sixties or seventies, would have been the scene of endless personal conflicts, of drunkenness, not of the hundreds, but of tens of thousands, and women and children could not have taken part ill such a gathering without the risk of personal injury. Yet here were only happy, smiling faces, women and children moving with perfect freedom, without even a thought that they were in the largest crowd of people ever brought together within a single enclosure upon the American continent, all feeling kindly toward each other, all taking part in the general joy and universal pride that this was the creation of their countrymen. The contrasts between the stage-coach and giant locomotive, between the birch-bark letter of the Indian and the telautograph message of Gray, the canoe of the Esquimaux and the electric railway, were not so great as that between the customs prevalent in my boyhood and this realization of hopes for a new civilization in the midst of which I walked on this Fourth of July, 1893.

Leave A Comment