The 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago exposed visitors to a new world. Many experienced what has been described as the “shock of the new” when facing awesome technological advances and the rich variety of human cultures on exhibition. Others felt a shock just from seeing the human form openly displayed.

“No one can help noticing the frankness and more than pagan un-reserve with which contemporary artists are treating the nude, both in painting and in sculpture.” wrote Julian Hawthorne in his critique of the art exhibits at the Fair. “It is a wholesome change. Self-consciousness only can be immodest.” Not everyone agreed, including two rubes visiting from Kansas.

This piece from the June 15, 1893, issue of the Fort Scott (Kansas) Daily Monitor is surely not a sincere World’s Fair correspondence but is instead meant to poke fun at simple country folk confronting worldly art. We provide some annotations and images to accompany the story of Joseph and Maria’s attempts to dodge visions of human flesh on the fairgrounds of the Columbian Exposition.

Nude Art in Chicago.

Joseph and Maria Have a Woeful Time.

They were looking at a statue that stands on the grass plot south of the Manufactures building. The statue was that of a young gentleman whose sole article of raiment was a strap about the left arm.[1]

“I call it scandalous, Maria, simply scandalous,” said the old gentleman, “and this Christian country, too; the idea of their putting that naked figger out there without even so much as a pair of trousers on him. I should think the people here would expect to be burnt up like Sodom and Gomorrah if they tolerate an exhibition like that.”

They hastened on to the beautiful white ships by the Administration building.[2] Two young men were discussing the ship and its fair freight. “Wonderful modeling,” said one; “look at the curve of that neck and back, and the pose and contour of that hip.” The venerable Joseph and his consort have one agitated look and precipitately fled. As they went Maria was heard to say, “and to see such things in a country that invented the sewing machine and the safety pin, it’s awful!”

Their flight led them to music hall, but when they reached its base one look aloft at the row of graceful, unblushing vagaries [3] sufficed to send them fleeing for their lives. Down past the long rows of fluted columns they sped, until they paused to eat the lunch which Maria’s careful hands had prepared.

Later in the day they were observed hesitating in front of the art building whether to venture in. Maria’s confidence was restored and they entered. For a time they reveled along the landscapes and marine.

But they presently brought up before a mermaid picture that made the little wife’s teeth chatter.[4] The old gentleman and his wife in their wild haste to get away blundered out into the rotunda among the statuary. Their first impulse was to retreat but fearing the baleful influence of the mermaid they tried to make a detour with averted eyes, but the frolicsome cupids and wonton druids would persist in obtruding a bare limb or a torso destitute of covering, and the distress deepened on their poor old faces as they tried door after door only to find them locked.

At last an open door leading to an empty gallery seemed to promise escape, but they found their passage blocked by a bronze young woman whose pedestal stated that her name was Caprice.[5] At any rate whatever her name was she was so rollickingly cheerful about her nudity that the couple gasped in horrified surprise.

They ventured into an apparently quiet gallery, and gradually took heart again until the awful “nude” again confronted them. This time two young ladies were discussing the picture, which bore the cheerfully irrelevant title of The Triumph of Faith.[6]

“What an air of piety,” said one. “What wonderful flesh tints; and isn’t that a marvel of foreshortening.”

“Do you mean to tell me,” snorted the now fully aroused Joseph, “that you can detect any piety about that picture? Can you overlook in what you call foreshortening and flesh tints the fact that these young ladies have neglected to cover themselves up when they went to bed?” But the feminine art critic said “These two poor girls are martyrs and have been thrown into a dungeon. Their clothing has been taken away. No one with an eye for either art of religion would see anything objectionable in their situation.”

“Nonsense,” retorted the worthy Joseph, hotly. “The painter didn’t see them that way, at least I hope not,” he added piously.

The old gentleman and his wife found their way out of the building, but before they left the grounds they stumbled across a roughly contrived screen of canvas, from behind which protruded suggestions of a plaster figure of quaint mold. Joseph would fain have investigated but Maria withheld him. “No Joseph,” she said, “these people don’t seem to be what you might call squeamish, and if they cover everything up it must be simply too awful.”

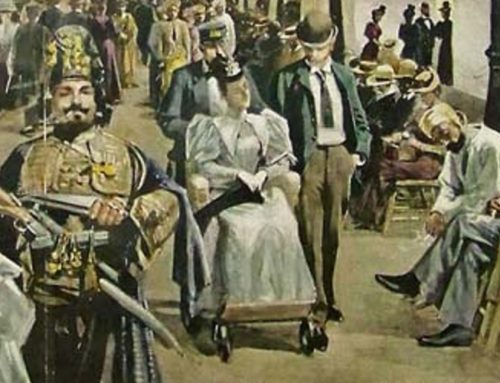

Examples of nude sculptures in the Palace of Fine Arts. [Image from the Keystone-Mast Collection, UCR/California Museum of Photography, University of California at Riverside.]

NOTES

[1] The image of a near-naked “young gentleman” that shocked Joseph and Maria was the statue of Neptune by sculptor Johannes Gelert, which surmounted one of the rostral columns on the Grand Basin just south of the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building.

A depiction of Neptune by sculptor Johannes Gelert stood on a rostral column outside of the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. [Images from Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume II. M. Juul & Co., 1894, and Flinn, John J. Official Guide to the World’s Columbian Exposition ... Columbian Guide Co., 1893.]

MacMonnies’ Columbian Fountain from the rear. [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894.]

Statues by Theodore Baur above the Music Hall. [Image from Keystone-Mast Collection, UCR/California Museum of Photography, University of California at Riverside.]

Raphaël Collin’s Au Bord de la Mer (1892), showing nymphs dancing on the sea shore, was exhibited in the French section of the Palace of Fine Arts.

[6] No painting titled The Triumph of Faith is listed in the Revised Catalogue, Department of Fine Arts. The description most certainly refers to St. George Hare’s canvas The Victory of Faith (1891) which hung in Gallery 15 in the British section. The striking oil painting depicts two Christian martyrs, a noblewoman and her slave, asleep in the nude on the eve of their imminent death in the Colosseum.

The Victory of Faith (1891) by St. George Hare. [Image from the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.]

SOURCES

Revised Catalogue, Department of Fine Arts. Conkey, 1893.

Jezzard, Andrew The Sculptor Sir George Frampton. University of Leeds Ph.D. thesis, 1999.

Phillips, Claude “Sculpture at the Royal Academy” The Art Journal 1891, vol. 53, pp. 261-62.

Phillips, Claude “Sculpture of the Year” The Magazine of Art 1895, vol. 18, pp. 67-72.

Leave A Comment