“To her belongs much of the credit for the strong feminist emphasis that characterized the Columbian Exposition.”

–James, et al. Notable American Women, 1607-1950, p 182.

Ellen M. Henrotin [Image from Pictorial Album and History of the World’s Fair and Midway. Harry T. Smith & Co., 1893.]

Educated in Europe, Ellen Martin moved to Chicago with her family in 1868 and a year later married Charles Henrotin, one of the founders of the Chicago Stock Exchange. Ellen joined the Chicago Women’s Club and in 1887 co-founded the Friday Club, a Chicago society supporting arts and literature. Through these and other social clubs, she addressed social reform issues such as the treatment of juvenile offenders.

While her husband served the World’s Columbian Exposition as a member of the Board of Directors, the Committee on Foreign Exhibits, and the Special Committee on Ceremonies, Ellen worked for the Women’s Branch of the World’s Congress Auxiliary (WCA), under President Bertha Palmer. This committee organized a program running the duration of the Fair, with nearly 6,000 addresses in 1,283 sessions. She describes women’s contributions to the sessions in her article “The Woman’s Branch of the World’s Congress Auxiliary,” published in the May 1893 issue of The Review of Reviews and reprinted here.

An advertisement for the National-American Woman’s Suffrage Association congress, listing Ellen Henrotin’s presentation on “Financial Independence” following introductory remarks by Susan B. Anthony.

Besides organizing sessions, Henrotin “faithfully put in personal appearances—frequently to make extemporaneous speeches when scheduled speakers failed to appear.” [James 182]. In her contributed paper for the Congress of Representative Women, “The Financial Independence of Women,” Henrotin does not equivocate:

“The entrance of women into the labor markets of the world marks a distinctly new era in her financial status, and the economic condition of woman is still a sad one. It is undeniable that the exhibits at the Columbian Exposition testify to the tremendous advance which she has made during the last half century in the industrial world, but it also testifies to the fact that in this world she occupies a very subordinate position: not numerically, but as a skilled artisan.”

“Mrs. Henrotin was progressive in her views, but she was not a suffragist,” writes Jeanne Madeline Weimann in The Fair Women. “She wanted the women in the congresses to speak, not primarily as women, but as lawyers, teachers, voters, social workers, to demonstrated that ‘woman is becoming as capable as man to take her part in this highly centralized and highly specialized civilization.’”[Weimann, 13] Other sources indicate that Ellen Henrotin did advocate for the women’s right to vote.

Mrs. Henrotin wrote a discerning piece about the displays in the Woman’s Building, titled “An Outsider’s View of the Woman’s Exhibit” and published in the September 1893 issue of The Cosmopolitan. She spiced her review of the art exhibits with frank opinions such as: “Woman has not as yet (if the collection in the Woman’s building is a faithful representation of her work) mastered the art of painting,” and “it seems a pity that when the patent books of the United States show such hundreds and hundreds of women’s names, that more might not have been represented [in the Woman’s Building exhibit of inventions.]” The criticism in her article reportedly “raised a tempest in a teapot” with some on the Board of Lady Managers. [Weimann, 320]

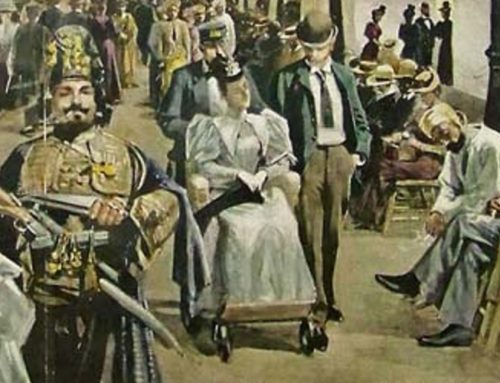

Ellen M. Henrotin [Image from Johnson, Rossiter A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Volume 4 – Congresses. D. Appleton and Co., 1898.]

SOURCES

Henrotin, Ellen M. “An Outsider’s View of the Woman’s Exhibit” The Cosmopolitan September 1893, p. 560-66.

Henrotin, Mrs. Ellen Martin “The Financial Independence of Women.” in The Congress of Women: Held in the Woman’s Building, World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, U. S. A., 1893. Eagle, Mary Kavanaugh Oldham (ed.). Monarch Book Company, 1894. pp. 348-353.

James, Edward T.; James, Janet Wilson; Boyer, Paul S. Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume 2. Harvard University Press, 1971.

Weimann, Jeanne Madeline The Fair Women: The Story of the Woman’s Building at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. Chicago Review Press, 1981.

Leave A Comment