Today marks the anniversary of the birth on January 3, 1840, of George R. Davis, Director-General of the World’s Columbian Exposition. The article below by comes from The World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 by Trumbull White and William Igleheart. J. W. Ziegler, 1893.

_________________________________________________________________________

INTRODUCTION

By Col. George R. Davis, Director-General of the Exposition.

When the gates of the World’s Columbian Exposition have been finally closed it will be time enough to impress its lessons upon the world. To attempt to do so now would be premature, and perhaps misleading. But since its glories have been unveiled to the public gaze, and its success has been assured, it is well enough to review the successive steps which have led to that success, and to present in a comprehensive way some of the features which will make it ever memorable in the annals of International Expositions. No one can appreciate fully the magnitude and the significance of the microcosm at Chicago in 1893 without some such knowledge as is herein presented, of how it came about that on the shores of Lake Michigan such wonders have been wrought.

Chicago possessed many well-supported claims, aside from the distance from the sea board, to furnish the ideal site for an ideal Exposition. In itself the phenomenal city—so gigantic, so young, so rich, strong and powerful—is the very essence of American progress. It is so essentially the most distinctively American of the great towns of the United States, that many other cities are foreign compared with it. To all discerning minds it consequently appeared eminently proper that the celebration of our four centuries of unexampled prosperity, of which this marvelous city is itself the apotheosis, should be held in Chicago.

Upon Chicago’s own part there was no sort of doubt as to her peculiar fitness for the undertaking, and she entered into the competition to secure it with characteristic energy and enthusiasm, both as unlimited as her strength and courage. It is now a matter of history that she won, and it is scarcely worthwhile to describe in detail the heroic measures resorted to, in securing the prize, over her older and subtler sisters. The pledged ten millions and more were raised, and a site acceptable to the National Commission was found. This was far more difficult than may appear at a glance, owing to the characteristically stupendous scale upon which Chicago immediately began the formulation of her Exposition plans. It was not easy to find commensurate space with improved surroundings. Jackson Park, the proposed location, was only partially improved, and owing to this fact the proposition of a divided site was made, and strange as it now seems, had many supporters. Gradually, however, with strenuous efforts, the makers of the World’s Fair struggled towards the light, and the site problem was finally solved by the acceptance of Jackson Park and Midway Plaisance upon the proffer of the same by the South Park Commissioners.

In this way was obtained a location of unexampled beauty and extent, stretching nearly three miles throughout its extreme length. Along the east front lies Lake Michigan, while in every other direction the Exposition grounds are bounded by the fringing tree tops of one of the vastest park systems in the world. Yet necessarily included in the magnificent site was a considerable amount of unimproved land, comprising a series of swamp and sand hill, and from this natural defect grew the most beautifying single feature of the entire landscape scheme. Grand basins and broad lagoons ultimately replaced swamp and unsightly sand hills, and resulted in the now famous Venetian effect of the World’s Columbian Exposition, which fills the beholder with dazzled delight. But this came only from months of Titanic toil, and the expenditure of vast sums, and following with all possible speed hard upon the preparation of the background came the process of actual construction of the main buildings. It is not easy to overestimate the stupendous character of this portion of the greatest enterprise of modern times. The utmost power of genius and many millions of money were unitedly brought to bear upon the execution of the infinite details of the general plan. The greatest architects in America designed the structures, the most skilled artisans executed their designs, famous artists supplied the ornamentation, while an army of humbler workers ceaselessly toiled still over the soil itself. Only those who were of this gigantic enterprise can grasp its immensity, the intricacy of the executive machinery of the Fair, the constant enlargement of plans, the addition of new structures, the multiplicity of detail, the enormous daily outlay required to keep in harmonious and perfect rhythm the many thousand picks and shovels and hammers, the conflicting ideas of the thousands of artists, sculptors, decorators, and finishers. Nor can any comprehensive impression be conveyed of the obstacles and discouragement from the elements, from wind and water, from fire and snow. Cyclones swept away the work of weeks in a lightning flash; Lake Michigan lashed by a furious tempest thundered threateningly against the very walls of the great Hall of Manufactures and Liberal Arts. Sailors, climbing to perilous heights which landsmen dared not attempt, laboriously cleared snow drifts from crushed roofs, only to find heavier flakes falling anew while they toiled. The second spring of Exposition preparations witnessed an unprecedentedly wet season, and its last winter was one of unexampled severity, yet not for a moment did the work flag. Enthusiasm bordering upon heroism, and zeal that was genuine inspiration, marked every division of the Exposition. Not an officer, not a workman, but subordinated self to the one end. There is a long list of names that should be emblazoned on bronze, and placed in Jackson Park, testifying to future generations of the worth and efficiency and self-sacrifice of men who made the Fair. Names of men who sacrificed time, personal ambitions, business interests and association with their families in order that the promise of the nation should be made good, and the gates of Jackson Park thrown open to the world at the appointed time.

While the enchanted White City—”The City of Aladdin’s palaces”—was thus magically springing from the mud of a primeval prairie, the national and international character of the World’s Columbian Exposition had become firmly established. State after State wheeled into line, making generous appropriation for buildings, and the collection of exhibits. I may be permitted in this connection to pay a well-deserved tribute to the Board of Lady Managers, which early after its organization gave material aid to the Exposition, in the direction of State representation. Indeed in the creation of the Board Congress contributed in an extraordinary way to the general success of the World’s Fair. As a body the Lady Managers have been economical and business-like; as an attraction, their building and their exhibits are among the most profitable to the Exposition Company. Their building, designed by a woman, is conspicuous for its architectural merits among all the beautiful creations of the Exposition. Its contents, wholly the work of women, attract and fix the attention of the visitor. For the first time in the history of international exhibitions, women have secured representation upon the Juries of Award. Foreign women have been placed in absolute control at Jackson Park, in positions where the sex would not be given an opportunity abroad. This is one of the educational features which American women at the Columbian Exposition confidently expect to impress on the sensibilities of Commissioners and other representatives of foreign countries.

As for the educational features of the World’s Fair, it is difficult to estimate them; the effect of the whole is so overwhelming. Conspicuous in this line is the historical character of several of the State buildings, notably the old Mission of California, the John Hancock House of Massachusetts, Virginia’s Home of Washington, Florida’s Fort Marion, and so on throughout an almost endless list. The typical nature of some of the State structures of the great Northwest are also worthy of comment. In fact these States and Territories have evidently been keenly alive to the opportunity, and have come with their richest offerings of precious metals, corn, and wheat. Bringing their superabundance of raw material to the departments of Mines, of Agriculture, of Horticulture and Forestry, they find its required complement filling the manufacturing sections in Machinery Hall, and the division of Manufactures and Liberal Arts.

Mexico, and the Central and South American Republics, our foster children, also promptly came forward, accepting the cordial invitation to participate, and are now here with handsome and interesting special buildings, enriching the entire Exposition with their wealth of cereals, precious metals, and priceless gems. Such a display of resources must do much to attract the attention of eager capital, and to establish advantageous reciprocal relations.

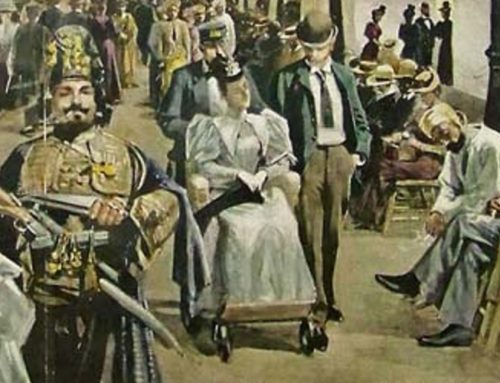

One after another in rapid succession the important countries of Europe, with scarcely an exception, promptly accepted the invitation to participation in the Exposition, extended by the President of the United States. Spain, who gave us Columbus, naturally comes first to mind, and occupies a distinguished position towards the World’s Fair. The splendid exhibits draped by the Spanish colors in every department, the quaint caravels anchored outside the peristyle, the official visit of the Infanta, are all eloquent of Spain’s prominence at the World’s Fair. While honoring Columbus, Italy, the land of his birth, naturally comes next to Spain in our consideration, and her cordial participation in the Columbian celebration is all the more highly appreciated, because it began at a time when diplomatic relations between that country and America were severed.

Of Germany’s share in the Exposition no praise can be extravagant. In every division of the classification her exhibits are superb; both comprehensive and magnificent. It is said that Germany has never before had an opportunity to show what she could do in the way of participation in an international exhibition. At World’s Fairs previous to the Paris Exposition, Germany took part only to a very limited extent, and the political situation naturally prevented her participation in the latter. At the Columbian Exposition Germany has covered herself with glory. She has poured out her treasures with lavish hands, and has brought us the ripest fruits of her finest mechanism, subtlest thought, and highest art. The millions of sturdy Germans who have become valuable American citizens, pursuing lives of honest prosperity in every section of the United States, are filled with delight and justifiable pride at the honor paid by the Fatherland to the country of their adoption.

Austria also is here with a splendid display, many fine paintings, and the inimitable Old Vienna of Midway Plaisance. The Nether lands have sent us their greatest pictures, and are assisted in the general exhibit by many thriving Dutch colonies. Great Britain’s colonies also have united to do her honor, Canada, Australia and New South Wales being pre-eminent. It is the exhibits of its Colonies, indeed, which chiefly distinguish the display of Great-Britain from that of our own country, which is one with England in blood, in temperament, in tongue, and in love of constitutional government. That we are still one and inseparate is evidenced in every corresponding branch of the classification; the same methods appearing in the English and American division of Mechanical Arts, and the same sentiments and sympathies glowing from its canvases in the palace of Fine Arts.

France too is here with her treasures of artistic skill, genius and art. A peculiarly close bond has existed between that country and ours since she lent us Lafayette in the hour of our desperate need.

Sweden, Norway and Denmark make magnificent displays. The latter was the only foreign country, strangely enough, which declined to appoint a committee of women to co-operate with the Board of Lady Managers, upon the preferment of a request from the Board to that effect. This decision was peculiarly and doubly singular, not only from the generally recognized progressiveness of the Queen, but because her Majesty’s daughters resident in other countries had been from the outset enthusiastic advocates of the World’s Fair, and the prominence of women in the making of it. This decision was, however, happily reconsidered, and Danish women are most creditable participants in the Exposition. The exhibits by these last named governments are of particular interest to the large Scandinavian population of the Northwestern States.

Belgium and Switzerland are brilliantly represented by characteristic displays. Indeed it were far easier to mention the nations who are absent—because they are so few—than those who participate. Russia came with the splendor that characterizes her. Russia has ever been the friend of the United States, and the presence of her mighty navy in American waters was a bulwark of strength to the loyal American heart, in the hour of our country’s terrible struggle. America in turn did what she could when she sent Russia bread in the anguished days of the famine, and Russia bears a tender memory of that. Her crops have been bountiful of late, and the vast empire has expended lavishly from its enormous stores, in sending a grand exhibit of its art and industries.

The Orient has not lagged behind Europe in coming to the World’s Fair. In truth the blood-red banner of Turkey, with its snowy star and crescent, was the first foreign flag unfurled over the World’s Fair grounds—with all the attendant imposing ceremonies of the Mohammedan religion. Japan’s snowy ensign with its large scarlet disk was also among the earliest colors unfurled. That country has indeed distinguished itself by the enthusiasm, the munificence, the extent, and the pre-eminent courtesy of its participation along all lines of the Exposition. Without question the already recognized generosity, amiability and fine breeding of the Japanese shine with increasing lustre at the World’s Fair.

It is much to be regretted that the strained diplomatic relations between our Government and that of China seem to have prevented official acceptance of our invitation to participation. But the World’s Fair management exerted such counteracting influence as lay in its power, by securing special legislation favorable to Chinese exhibitors, and private firms profited by this effort although the Government did not, and the World’s Fair is consequently not without the unique attraction of a Chinese exhibit. Burmah and Siam have placed in evidence their unrivaled wares, and wondrous specimens, wrought in costly threads of gold and silver, of their characteristic fabrics.

It is scarcely necessary to name in turn each of the countries contributing to the vastest of World’s Fairs. Suffice it to say that all the considerable nations of the earth are here. Nor need separate mention be made of its many great divisions. It is now generally known that there are thirteen of these, conducted by “Chiefs” of eminent ability, whose representatives have ransacked the world for the treasures of art, science and industry, for the benefit of the Exposition. Nor need the dimensions of the buildings provided for the best the world has produced be reiterated, although the untechnical mind does not readily grasp the real extent of a bare statistical statement. The generality of persons understand more fully when told that nearly twice as much steel and iron enter into the construction of the giant hall of Manufactures and Liberal Arts than was required for the Brooklyn Bridge. Or that the pyramids of Cheops might be stowed under its great glass roof—which covers nine times as much ground as is occupied by the Capitol at Washington. Time was, two and a half years ago, while the making of the Exposition was yet to be achieved, when these stupendous facts needed to be told over and over again in necessary exploitation of the enterprise. The Department of Publicity and Promotion—to use Tony Lumpkin’s words—”kept dinging it into” the whole reading world. Never had any previous Exposition been so extraordinarily and admirably advertised as was our own. No Department corresponding to that of Publicity and Promotion had ever existed before, and its remarkable work was accomplished along unexplored lines, without a precedent of any description to guide it. But it succeeded in the aim; it bore the tidings of the great work going on at Chicago from Dan to Beersheba, from New York to Paris, from Iceland to Egypt.

But the glowing promises made by the World’s Fair writers are fulfilled now. There is nothing more to say save to invite visitors from far and near to behold the indescribable realization of these dazzling prophesies. To gaze upon such a scene of enchantment as was never before dreamed of outside oriental tales. A city of ivory palaces, embodying architectural dreams. Classic creations which stir the appreciative heart, and might have stood pre-eminent for their unapproachable beauty in the Athens of Pericles. The sculptured facade of the Grand Court, the stately colonnade of the Peristyle, through and above which gleam lake and sky as blue as the lakes and skies of Italy. On every side are columns and statues, the heroic figure of the Republic lifting its graceful proportions high above the silver waters below. We have covered the gigantic figure of the Queen of Freedom with gold, as the Athenians did that of Minerva. There are gilded domes also, and flashing minarets, the flags of all nations, and gay gonfalons galore. When the sun sinks out of sight and shadows creep over the lake, one by one the circling line of electric lights outlining the ivory facade gleam forth like endless strands of luminous jewels, and the dome of the Administration Building glows like the most stupendous of exquisite cameos.

But all this is brilliantly in evidence, and gloriously beautiful though it is, represents after all only the material portion of our great Exposition. The Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in its own modest way showed what an International Exhibition can do for the country in which it is held. It put us forward a quarter of a century in the cultivation of taste, in the elevation of the standards of artistic workmanship, in the adaptation of the methods of older or more advanced civilizations to the needs of the newer continent, and in raising the masses to a plateau of higher intelligence. The benefits conferred by the Chicago Exhibition will exceed those of the Centennial in proportion to its greater artistic achievements and greater comprehensiveness in every department of human activity. These ideal buildings will influence the architecture of our own country—and indeed of the whole world that gazes upon it—for an indefinite period. The treasures of industry, science and art forming their contents, will be reflected in the pictures, fabrics and manufactures of many subsequent years. This will be the visible, artistic and commercial result of the World’s Columbian Exposition. The subtler, intellectual and spiritual outcome is farther to seek and more difficult to foresee. It must, however, perforce include the stimulating influences born of the commingling of all races of men. Perception of the best each nation has to present must direct and invigorate to the elevation of individual and national life. The revelations of the World’s Fair have already corrected many erroneous international opinions. The best thought, the most advanced methods of all countries in science, literature, reform, education, government, morals, philanthropy, jurisprudence—indeed, all those things which contribute to the progress, prosperity and peace of mankind—are exhibited in the Exposition itself, or discussed in its Auxiliary Congresses. The intense interest aroused by the latter has been evidenced by the attendance of many of the greatest leaders of thought in both Europe and America. The Rulers of other countries have sent special envoys to our Exposition; with injunctions to observe our institutions, customs and privileges, with a view to the adoption of the most advantageous. We in turn are eagerly scanning the foreigners, alert to learn the best they have to teach. From such conditions lasting results of incalculable benefit must certainly come.

Leave A Comment