Frank Lloyd Wright was known for his Cherokee red, and Maxfield Parrish had his own blue. Diana Vreeland was known for wearing red, and Shelby Latcherie’s colors were “blush” and “bashful” (a.k.a “pink” and “pink”). Icons often have a signature color.

In October of 1892, Chicago excitedly prepared for her coming out ball. The world soon would arrive to see the Fair, and downtown businessmen decided to decorate their city for the occasion. Chicago needed a signature color.

An object of absorbing interest to all the world

The Congressional bill passed in the spring of 1890 authorizing the World’s Columbian Exposition stipulated that the Fair would open in May of 1893. In order to commemorate the quadricentennial of Columbus’s arrival in the New World, the Exposition held a Dedication Day on Friday, October 21, 1892 (several days after the precise landing date of October 12, 1492). Hundreds of thousands of citizens and scores of dignitaries poured into the partially completed fairgrounds for a ceremony of barely heard speeches, roughly performed music, and dreadfully long poetry inside the cavernous Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building.

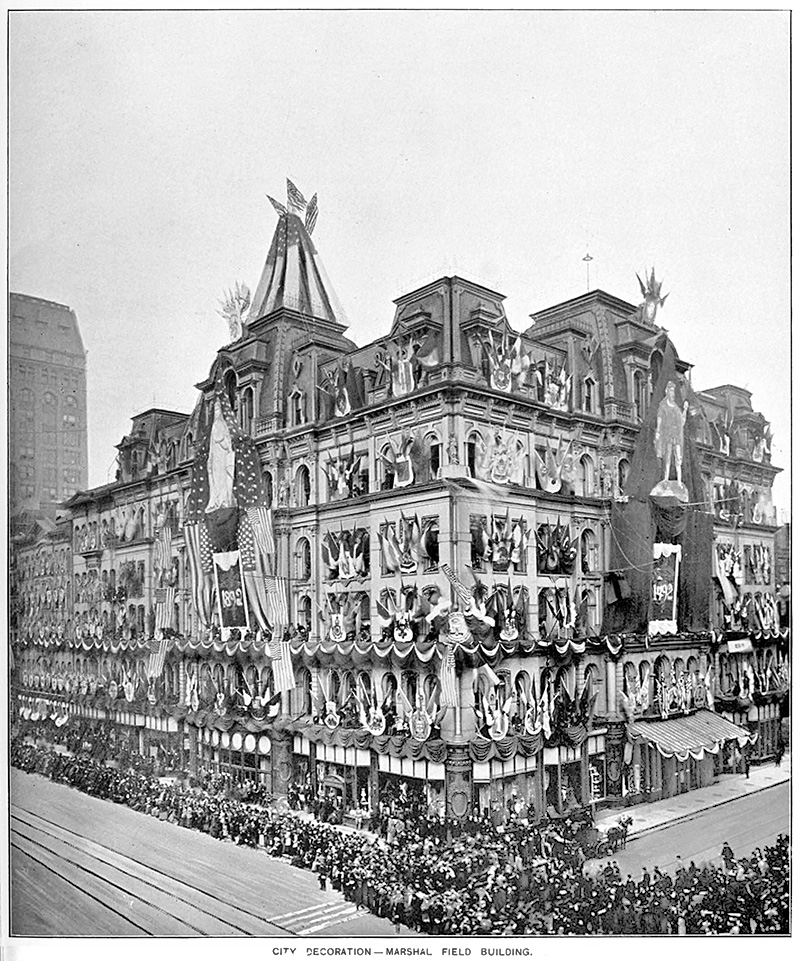

A more successful show happened in downtown Chicago, where buildings featured splendid decorations. Civic spirit and leadership from the business community transformed the Chicago Loop into a festive display for Dedication Day.

“Nothing connected with the important event of the dedication of the great Exposition went off with more success and éclat than the city decorations,” recorded one Columbian Exposition history. “All Chicago was one bright picture, and inasmuch as the city had had little or no previous experience in general decorations of its buildings, the result was a most happy and gratifying surprise.”

James W. Scott, the publisher of the Chicago Herald, proposed that owners and lessees of the principal buildings in the Loop should dress their properties with adornment “both artistic and attractive, and devoid of the common-place features which usually characterize such decorations” making Chicago “an object of absorbing interest to all the world.”

Harry G. Selfridge of Marshall Field & Company served as chairman of the decoration committee, comprised of a team of 87 prominent men of the city.

Shown here decorated for Dedication Day in October 1892 is the Marshall Field and Co. store at State St. and Washington St. in downtown Chicago. [Image from Dedicatory and Opening Ceremonies of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Stone, Kastler & Painter, 1893.]

One special color

Director of Color Francis (Frank) D. Millet selected the official municipal color, something “appropriate for a general back-ground on which the brighter and more delicate colors could be displayed to great advantage and with harmonious combinations.”

Dedicatory and Opening Ceremonies of the World’s Columbian Exposition records that the great success of the decorations was dues to “the wisdom in choosing one special color which might be run in varying shades through all the myriad decorative designs and forms which were displayed on the grimy stone fronts and severe architectural ensemble of Chicago’s massive buildings. The people accepted the selection with a unanimous good spirit, which made it truly the ‘municipal color.’”

What became Chicago’s signature color? Terra cotta.

SOURCE

Dedicatory and Opening Ceremonies of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Stone, Kastler & Painter, 1893.

Leave A Comment