PART I: DECORATING THE DOME OF THE ADMINISTRATION BUILDING

“Fame comes only after death to those who have slaved during life.”

—William de Leftwich Dodge

The gem and crown of the Exposition

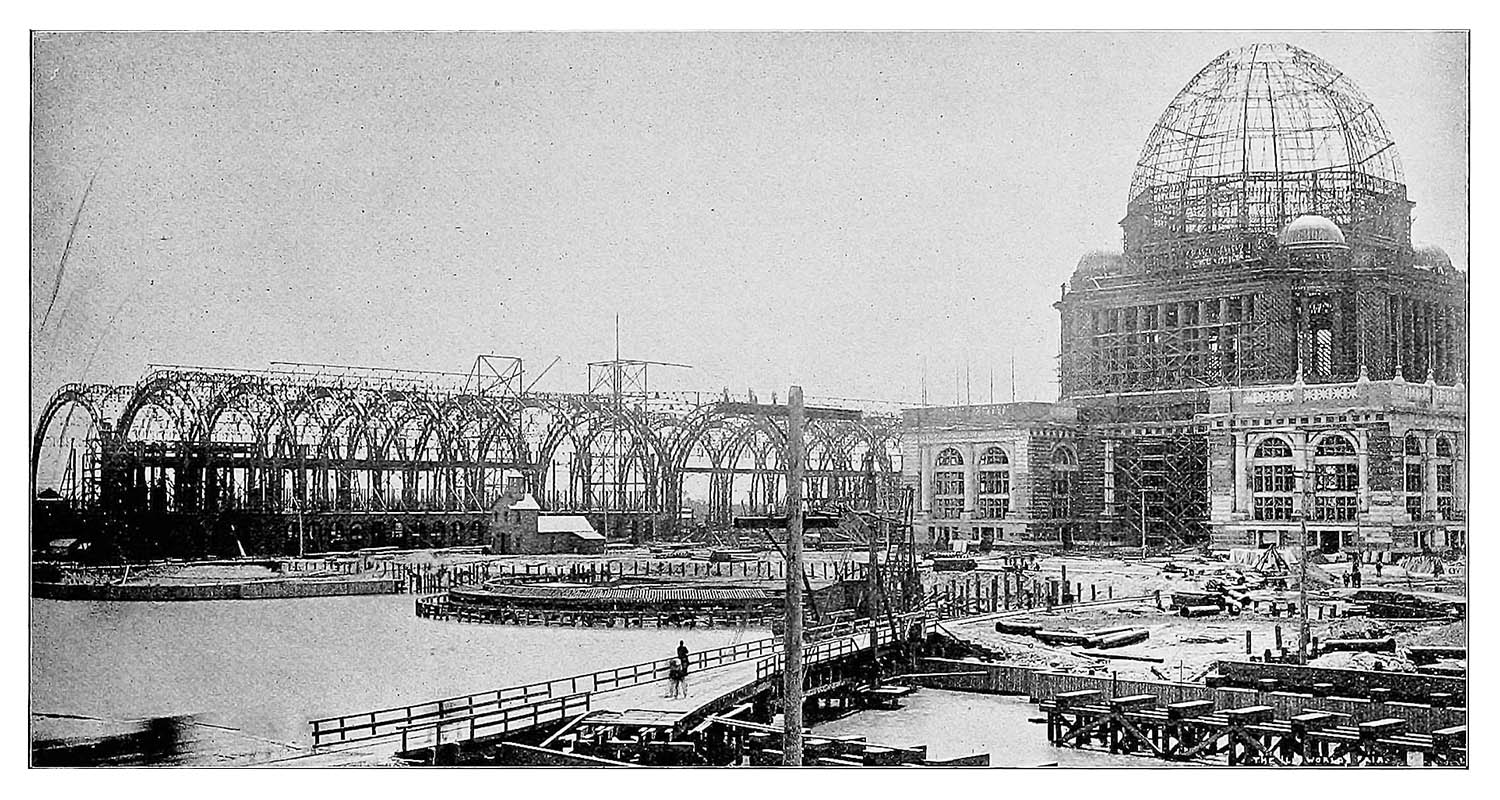

Along with the Ferris Wheel and the Statue of the Republic, this magnificent structure is one of the most iconic images of the 1893 World’s Fair. With its grand and golden dome, the Administration Building towered over the fairgrounds from a commanding position of honor at the west end of the Grand Basin (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A portion of Thomas Moran’s watercolor painting Chicago World’s Fair (1894) showing the Administration Building dome exterior at sunset. [Image from the Brooklyn Museum.]

“There is no dome in this country to which this one can be compared,” proclaimed Columbian Exposition historian Benjamin Cummings Truman. “It is finer in every respect than any other on the Western Hemisphere” [Truman, 204]. Another contemporary chronicler called it “the gem and crown of the Exposition Buildings” [Moseley, 192].

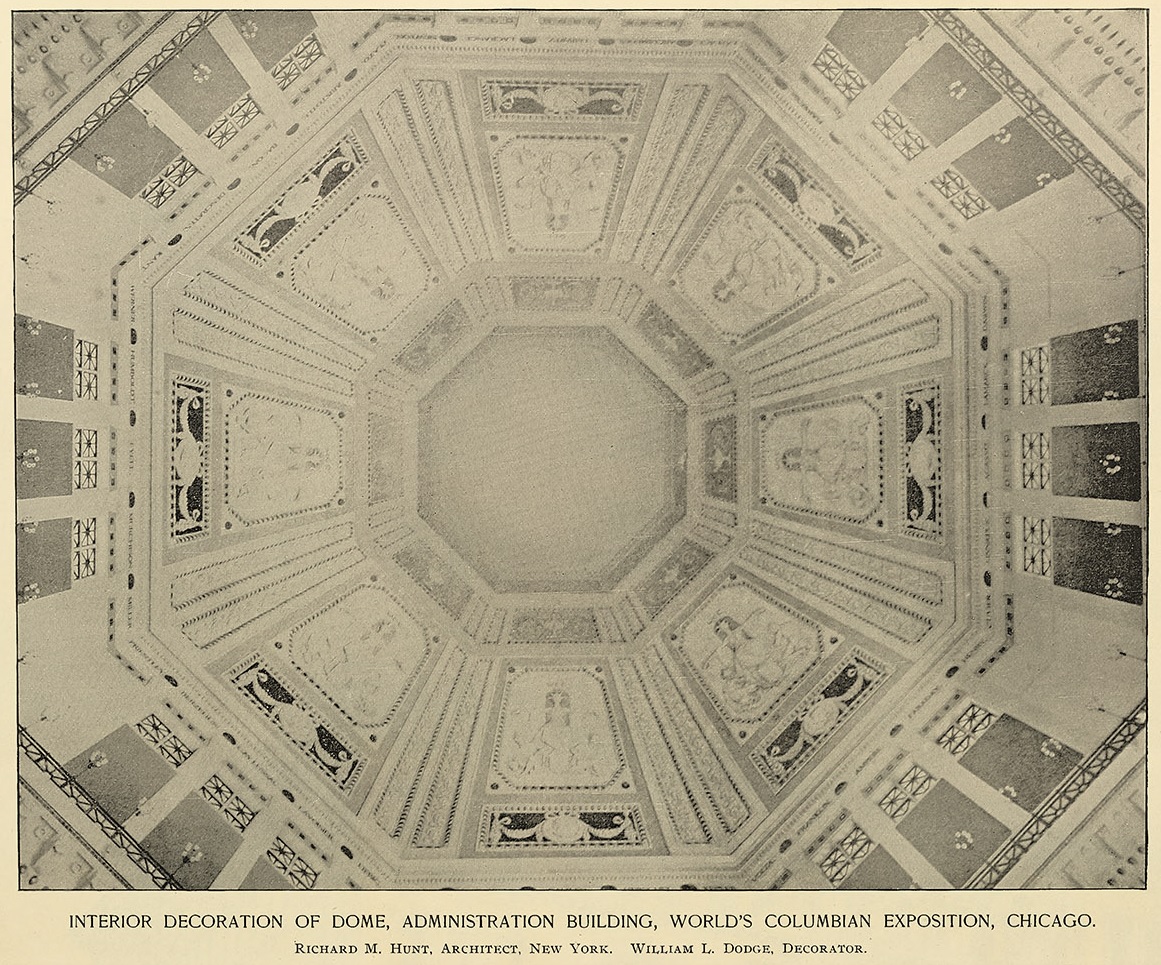

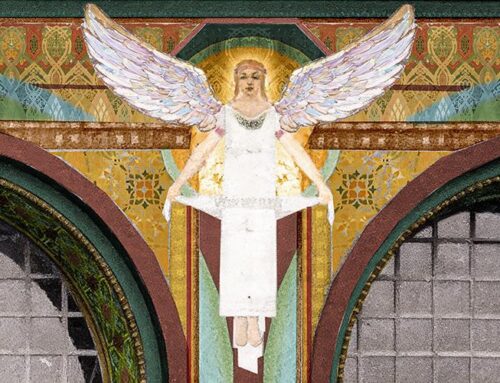

While no visitor to the fairgrounds could miss the glistening, gilded exterior of the Administration Building roof, how many ventured inside its octagonal-shaped central rotunda and looked directly up? Two hundred feet above the floor, at the interior top of the dome, an opening 50 feet in diameter allowed sunlight into the rotunda and illuminated the interior of the dome. Wrapped around this oculus was the largest painted surface at the Fair, a mural 315 feet in circumference and 40 feet from base to apex titled The Glorification of the Arts or The Glorification of the Arts and Sciences (Figure 2).

“The artistic decorations on the interior of the dome of the Administration building,” reported World’s Columbian Exposition Illustrated, “is one of the most remarkable pieces of mural painting for the Fair.”

Figure 2. The interior decoration of the Administration Building dome. The Glorification of the Arts mural, not visible in this photograph, occupies space in the central octagon. [Image from the Inland Architect and News Record Vol. 22 No. 5, p. 242.]

So young in years

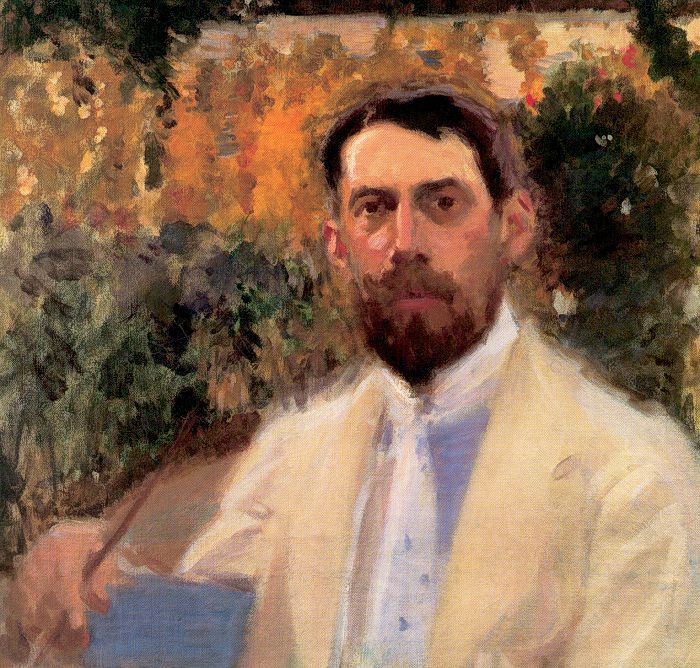

The job of preparing the largest painting at the 1893 World’s Fair went to the youngest painter working on the fairgrounds. Born on March 9, 1867, in Bedford, Virginia, William Leftwich Dodge (Figure 3) had lived in Chicago from 1869 to 1879 before moving to Europe with his mother, also an artist. Sometime around 1890 he adopted the middle name “de Leftwich” in accordance with the family’s English ancestors. [Pisano, 32] Dodge turned twenty-six years old while working on Glorification, his first important commission.

Figure 3. A portrait painting of William Dodge, ca. 1898, by his close friend the American sculptor and painter Frederick MacMonnies, who created the Columbian Fountain just east of the Administration Building. [Image from the Library of Congress.]

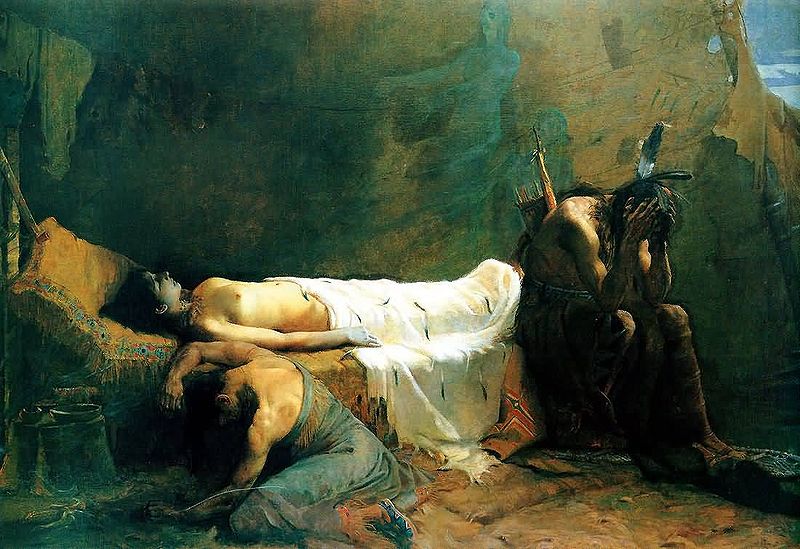

His large painting The Death of Minnehaha (1885-87) (Figure 4), based on William Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem The Song of Hiawatha, won Dodge a gold medal at the Prize Fund Exhibition in New York in 1887 and became one of his best-known works. It also demonstrated the young artist’s promise for creating a painting on the vast canvas being planned for the Columbian Exposition’s showcase building.

A prescient art critic in 1891 recognized this promise, auspiciously noting:

“While it is true that art knows neither age nor nation, the fact of this lad having successfully handled pictures of such a size is certainly remarkable. I think that Mr. Dodge is far from having reached the fullness of his development, and that, could he be given large wall spaces to work on, we should probably have in him an artist who would make his impression on the nation.” [Fraser, 798]

Figure 4. Dodge’s The Death of Minnehaha, in the collection of the American Museum of Western Art – The Anschutz Collection.]

Hardly enough to pay for the paint

While living in New York in 1891 and preparing artwork for Collier’s, Scribner’s, the Century, and other magazines, Dodge heard about the World’s Columbian Exposition being planned for Chicago in 1893. The artist headed to Chicago to prepare sketches, hoping to gain work painting murals for buildings on the fairgrounds. Failing to earn any commissions for the Exposition, he stayed in the city to working as a painter on a huge Cyclorama of the great Chicago fire of 1871 (Dodge had been living in the city during that historic tragedy!) being installed as a downtown amusement. [Kimbrough, 41]

Figure 5. Photograph of architect Richard Morris Hunt (1827–1895) [Image from Architectural Record October-December, 1895.]

“He told me to get busy and make him a sketch showing my idea. I rushed back to my studio, composed a sketch 5 by 5 feet, worked on it all night, and took it to his office the next day at twelve o’clock with a written description of the subject. He was amazed at the short time I had taken; thought it would take a week. He was delighted with it and said it was just the kind of thing he wanted.” [Platt, 58]

With only $5 in his pocket, Dodge returned to Chicago by train that night to begin his work.

Although Dodge wrote his autobiographical notes in 1933—so we could forgive him if some of his recollections were fuzzy after forty years—much of his memoir is supported by records from the time of the Fair. One news story in 1893 reported that the mural commission earned Dodge $4000 [“Artistic Decorations”], but Burnham’s final report confirms a commission of $3,000. [Burnham, 72] Another contemporary report states that it was Director of Decorations Francis D. (Frank) Millet who selected Mr. Dodge to do the mural [Harper’s Weekly], but most likely this meant that Hunt recommended Dodge for Millet’s final approval. As head of the decorations department, Millet (or his predecessor, Director of Color William Pretyman) approved all contracts with the artists employed by the Fair. In his final report to Director of Works Daniel Burnham at the close of the Fair, Millet noted that, as of June 1, 1892, William Dodge “had been promised a contract” for his dome painting. [Burnham, 57]

Figure 6. “Present Appearance of Horticultural Hall” at the time when William Dodge established his studio there. [Image from The Illustrated World’s Fair, June 1892 ]

Take that naked lady off the roof

Dodge began his work on June 8, 1892. [Burnham, 59] Artists working on the Exposition fairgrounds had access to a large part of the Horticulture Building (Figure 6), and here Dodge established his studio and began preparing drawings. He invited his brother, Robert Dodge, also an artist, to come to Chicago from Paris and join him as an assistant.

Along with the artists working on dome murals for the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building (James Carroll Beckwith, Edwin Blashfield, Kenyon Cox, Robert Reid, Charles Stanley Reinhart, Walter Shirlaw, Edward Simmons, and J. Alden Weir), the Dodge brothers were provided with a small plaster dome model to use for experimenting with perspective painting on a curved surface. The artist recalled working on a 15-foot-diameter model of the dome that weighed two tons. [Platt, 58] In an interview with the Chicago Inter-Ocean, Robert Dodge explained their work on this smaller study of Glorification:

“The composition … was painted in a small dome, about sixteen feet in diameter and seven feet high. It was an exact miniature of this one. In making this miniature we got an idea of the difficulty of painting on the concave surface and yet retaining the proper proportions of the figures. The models were placed on a high platform in Horticulture Hall, and standing below them, we would transfer the figures to the little dome. When we came to enlarge the figures small squares were cut to correspond with the original drawings. These were enlarged many times and given their appropriate place in the great dome” [“Decorative Features”, 156].

Dodge recruited men working on the fairgrounds and women from the city to serve as models for his composition and had stages built in the studio for them to pose on. The work with these figure models was not without incident.

“One day the girls arrived at the studios weeping and told that they had been put out of their boardinghouse because they were ‘artists’ models,’” reports Sara Dodge Kimbrough, Dodge’s daughter, in her biography of the artist. “However, new arrangements were made, along with proper explanations, and they were again housed and well treated. [Kimbrough, 44]

William Dodge recalled an amusing episode that occurred while he prepared his studies for Glorification in the Horticulture Building studio during the warm season:

“I had a half-nude model posing through an opening in the roof to make a color sketch against the sky. I had not been working long when all the work on the fair stopped. A guard was sent up to my studio with an order from headquarters to take that naked lady off the roof as all the workmen had stopped work to get a look at her.” [Platt, 58]

Figure 7. The state of construction of the Administration Building circa June 1892 when Dodge began working in his studio in the Horticulture Building. [Image from The Illustrated World’s Fair, June 1892, p. 237.]

At dizzying heights inside the dome

Delays in construction of the White City buildings caused frustrating postponements for many artists employed by the Exposition who desperately wanted to begin their decorative work. This was especially true for the Administration Building (Figure 7), which was more than five months behind schedule and the cause of a public dispute between Dodge and Millet over personal expenses incurred by the artist during this delay. [Bardin, 36]

In his memoir, Dodge stated that he had worked on the Fair commission for “two winters,” but his time on the fairgrounds only spanned eleven months; perhaps the intensity of the winter of 1892-93 made it feel like two years. The work to paint his mural inside the Administration dome presented two enormous physical challenges: heat and height.

A reporter from the Chicago Tribune visited Mr. Dodge on the fairgrounds and wrote that the artist “does not know from the time he goes aloft until he comes down what the weather is. The forest of scaffolding in the dome of his building is so dense that he cannot be seen from the earth.” [“Rush and Chisel”] Dodge, however, was acutely aware of the bitter cold he had to endure during the winter months painting the ceiling of the unheated building. He described the conditions as “terrible.” [Platt, 58]

Dodge also remembered the “exhaustive” daily climb up hundreds of feet on steep ladders to reach the painter’s platform inside the dome (Figure 8). Before starting work inside the building, Mr. Dodge inspected the scaffolding and reported that it would be strengthened before he entrusted it with the lives of himself and his assistants. [Kimbrough, 43] A fall could have been fatal.

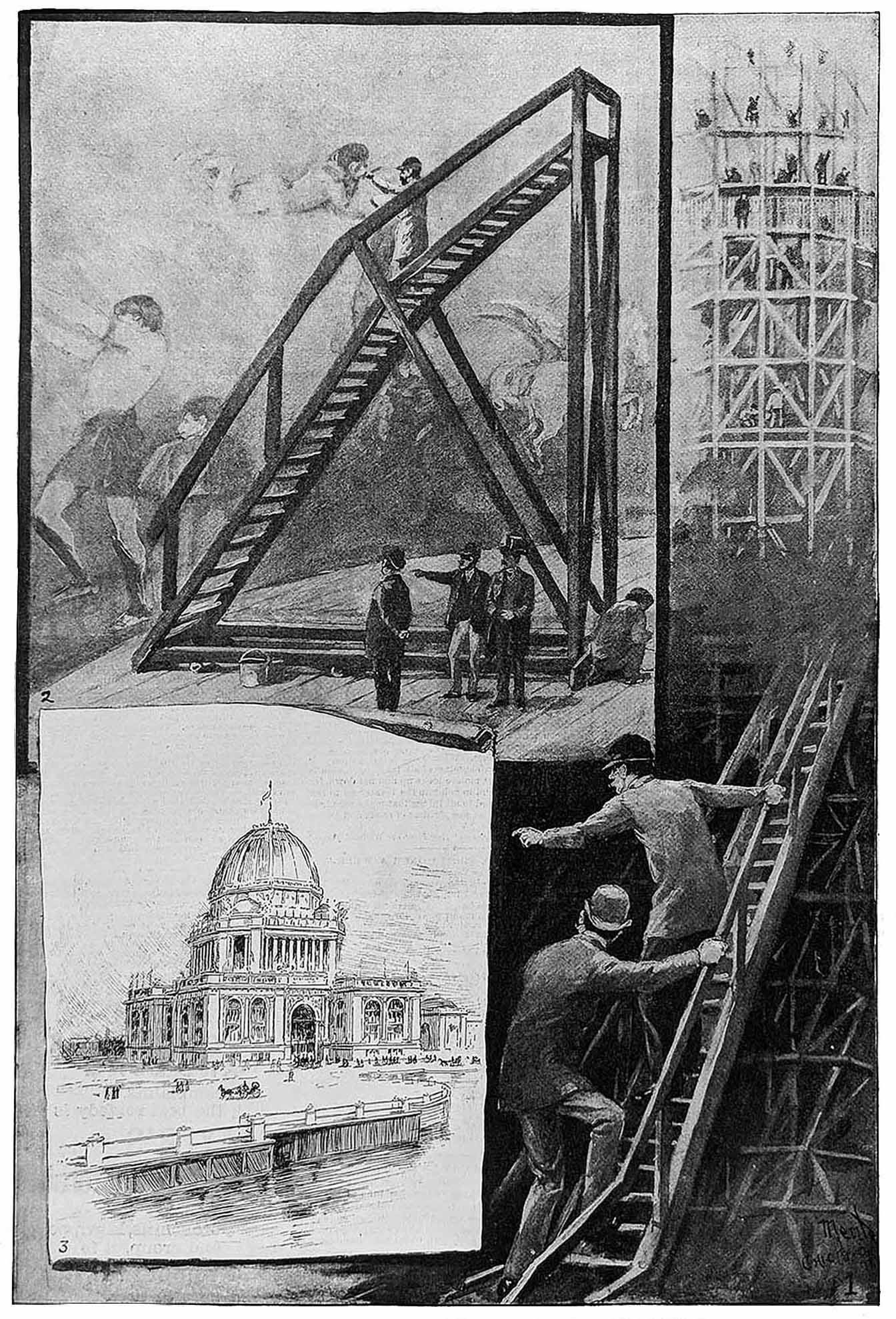

Figure 8. An illustration from Collier’s Once a Week Vol 10, No. 2, showing (1) artists climbing the paint scaffolding, (2) an artist decorating the dome as he works on angelic figures in the sky, and (3) a general view of the Administration Building exterior.

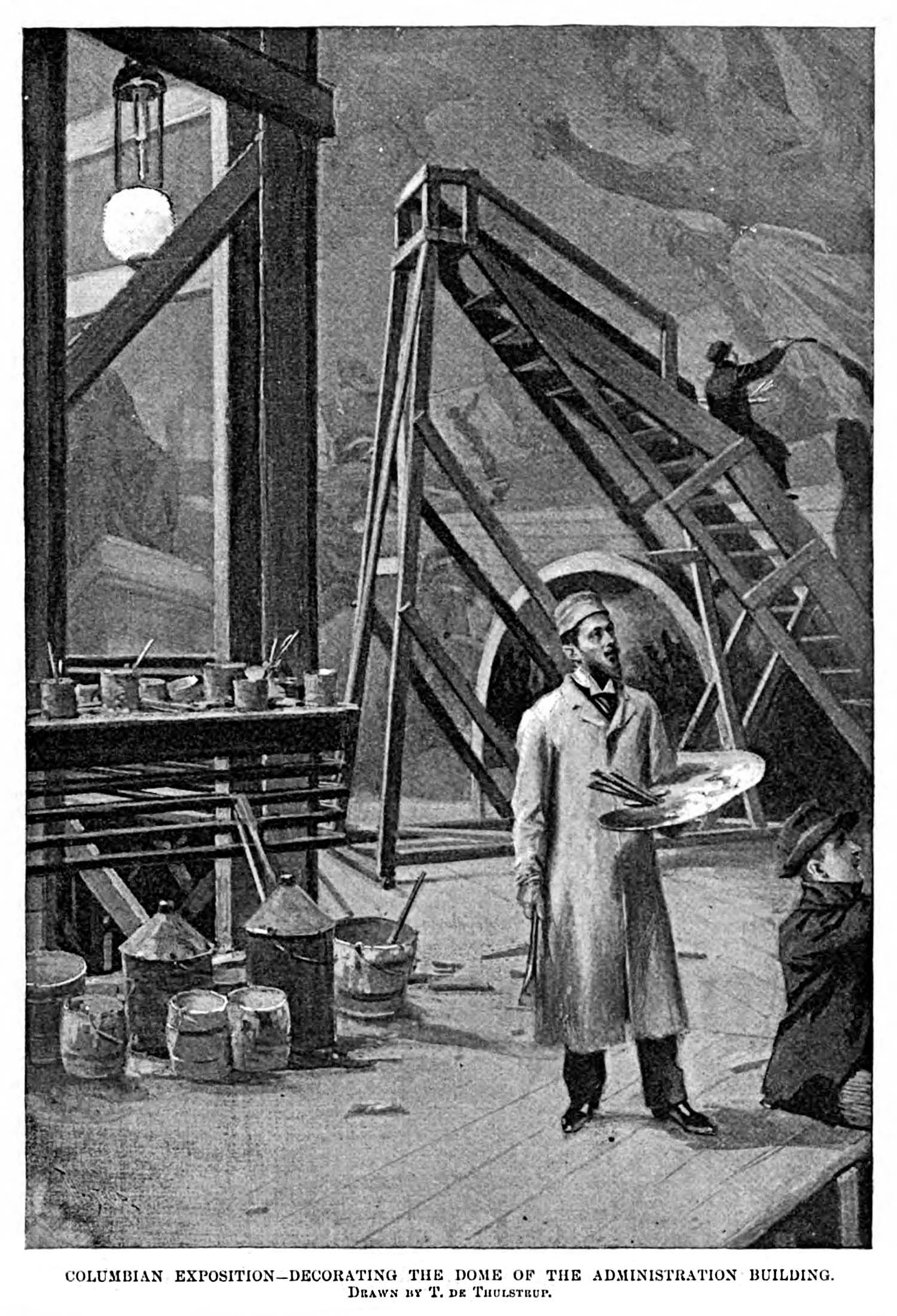

This description from Harper’s Weekly gives a sense of the arduous daily task inside the dome:

“A visit to Mr. Dodge at work is exciting to one unaccustomed to tread the rounds of ladders at dizzying heights. Indeed, it is alarming to timid souls, for after climbing a narrow winding stair till breathless, the visitor finds that the rest of the distance must be by means of a vertical ladder on the outer wall of the inner dome. And during this ascent the visitor is in almost complete darkness. Presently you emerge from this darkness upon a circular platform, and there you meet Mr. Dodge, the presiding genius of the place, very much as Mr. De Thulstrup has represented him in his picture (Figure 9). This room, of which the platform is the floor, is furnished principally with colors and brushes, with a small plaster model of the dome in two pieces, and a sort of stepladder on wheels, which can be rolled from side to side of the surrounding walls as the painter desires to work at different parts of his fresco. While the painter is at work close to the figures he is making, one realizes how much these figures have to be exaggerated so that they will look all right from the ground when finished. Man is but a pygmy compared with them. It is quite impossible for a layman to judge as to how effective these figures will be when the scaffolding is removed and they are viewed from the ground.” [“Mural Decorations”] Although the relatively new technology of electric lighting provided the painters with helpful illumination of their work surface, it also extended their work hours well into the night. They often did not come down from working until after midnight. [Kimbrough, 44]

Figure 9. “Decorating the Dome of the Administration Building” by Thure De Thulstrup for Harper’s Weekly April 8, 1893. The artist in the foreground is William Dodge. The painter on the steps is working on Apollo’s robe.

A crowd watched from below, holding its breath

In the months prior to the opening of the Fair, the Exposition management invited the public to visit the fairgrounds and pay a fee to see construction activities. Thousands came daily to watch the White City emerge. Dodge’s daughter reports an interesting story about the artist and architect of the headquarter building of the Fair:

“One morning after the Administration Building’s dome was completed and the scaffold removed, Father was asked by Hunt to touch up a small section of the mural. With his usual lack of fear he climbed the 250 feet on makeshift ladders and made the changes while a crowd watched from below, holding its breath.” [Kimbrough, 45] Although the April issue of Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly described the mural as being “not yet finished,” the April 1 issue of The Critic reported that “Mr. William Leftwich Dodge has just finished his decoration of the dome of the Administration Building.” Either way, Dodge did complete his painting in time for Opening Day of the Fair on May 1, 1893, when hundreds of thousands of visitors gathered around (and on) the Administration Building.

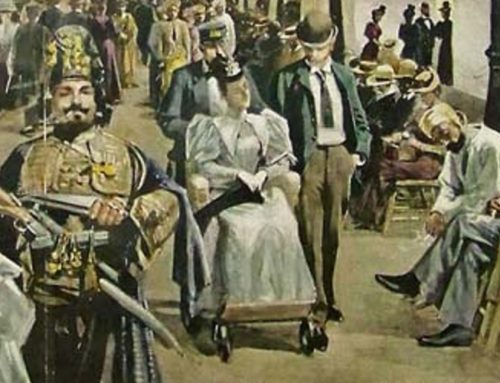

At the Opening Day celebration, William and Robert Dodge, along with friend Frederick MacMonnies, whose glorious Columbian Fountain graced the end of the Grand Basin in front of the Administration Building, reflected on their accomplishments during the festivities:

“With bands playing and flags flying, they stood in the White City of Dreams, lighted by thousands of Edison’s new incandescent lamps, amidst throngs of mustachioed men in bowlers or high silk hats and women in sweeping gowns with leg-o-mutton sleeves, and looked across MacMonnies Fountain and the lagoon. Their memory of hazards and hardships vanished as the fountain danced and the lagoon reflected the majestic Administration Dome on which they had labored so long.” [Kimbrough, 45] His work done for the Fair, Dodge returned to New York “with hardly a cent left,” due to bank failures during the Panic of 1893 and his own bad investments.

Walking beneath The Glorification of the Arts and Sciences on Opening Day were President Grover Cleveland and his cabinet, all the Columbian Exposition officials, a group of Lakota, and countless visitors. A few weeks later, the Princess of Spain and her entourage also would cross the grand rotunda. Among the millions attending the Fair, how many looked up to see the Dodge’s decoration inside Administration Building dome?

[Part II of this article describes the composition of Dodge’s Glorification of the Arts and Sciences and some vestiges of this lost painting. References and Acknowledgements accompany Part II.]

Excellent, well-researched article on a magnificent but little-remembered story from the Fair. Look forward to the conclusion of the article!