The Great Transformation Scene

This is Part 10 of our series “Opening Day of the World’s Fair,” which explores the events of May 1, 1893, at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The full series can be found here.

As the last words fell from his lips at the conclusion of his short address, President Grover Cleveland placed his finger on the telegraph key. With his hand touching the electric switchboard, a chrysalis transformation scene was about to begin on the fairgrounds.

The world was waiting at the end of a telegraph wire

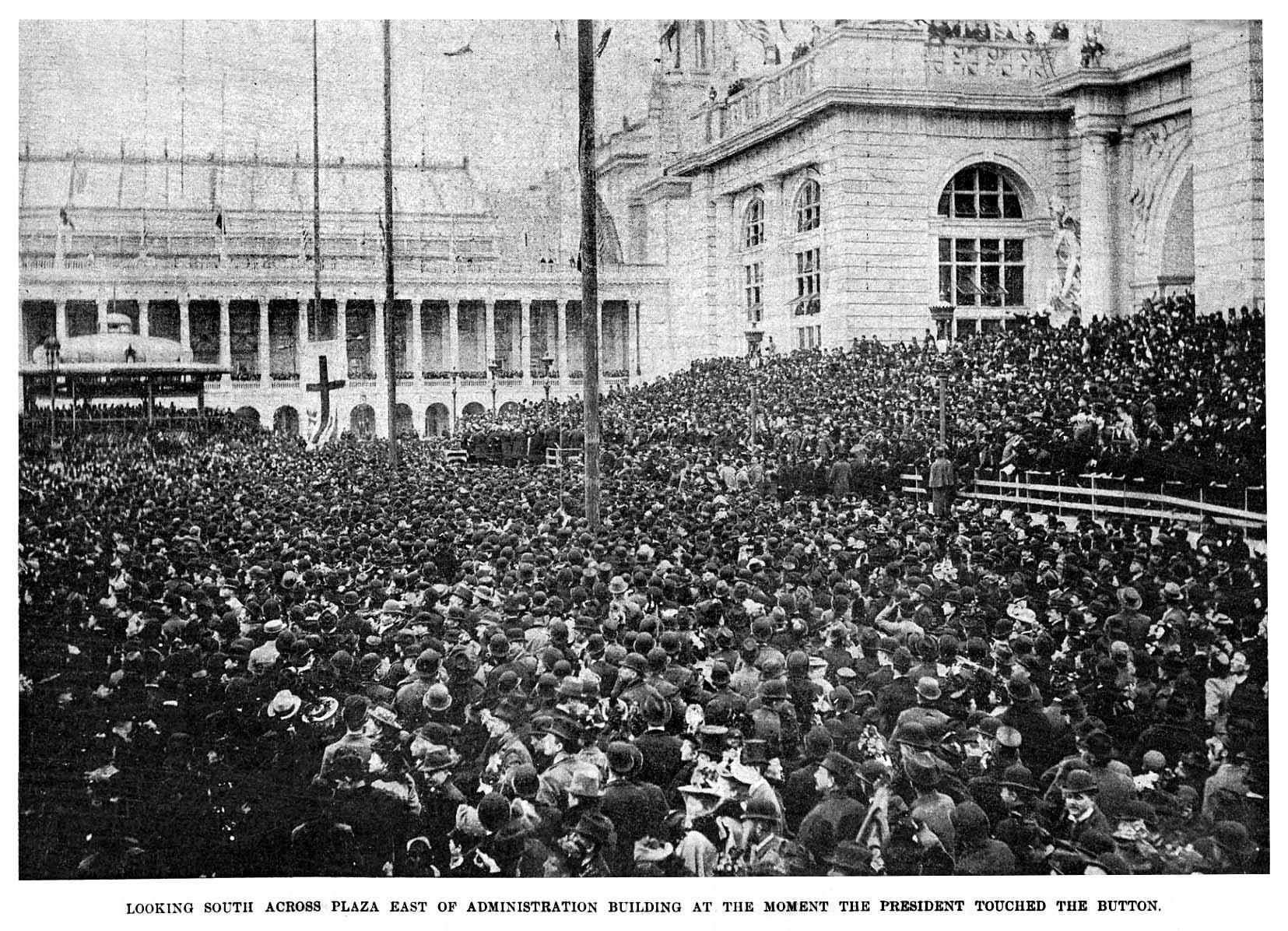

This instant of expectancy was too short to be measured and yet long enough for each of the hundred thousand human beings to feel a nervous tremor and to unconsciously prime their lungs for a shout that might express their emotions. The world was waiting at the end of a telegraph wire.

The crowd leaned yearningly forward, silenced and earnest in their eager expectation, as the president slowly lowered his hand to the electric key. The Indians assembled high above along the Administration Building balcony pressed against the rail to witness the event. The electric current—by the lightest touch and in an instant—would set the vast machinery of the Exposition in motion. The electricity was not swifter than the current of sentiment that leaped, like the lightening’s flash, from mind to mind.

“The Electric Button” [Image (colorized) from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, May 18, 1893.]

The magic key

“Electric Button” stereoscope card photograph. [Image (colorized) from the New York Public Library Digital Archive.]

The magical golden emblem was delicate in construction and exquisite in finish and equipment. “Old timer” telegraph operators in the crowd knew that only a light pressure would be needed to bring the two key points together.

Grover Cleveland, however, had no such experience. When the moment arrived for him to “touch” the delicate key, he did so with a force suggestive of his first tariff reform message to Congress. With a gesture visible to the remotest edge of the crowd, the president brought his hand down with such might that he nearly shattered the memento of the great event.

Grover Cleveland’s finger did a million things

“President Cleveland Pressed the Button” from the Chicago Inter Ocean, May 2, 1893.

At 12:20 o’ clock, the president pressed the key that set the machinery in motion and signaled the opening of the World’s Columbian Exposition. That single touch of Grover Cleveland’s finger did a million things on the fairground. In the larger world, it marked on the page of history the beginning of another epoch in the life of man: the planting of civilization’s center within the interior of America.

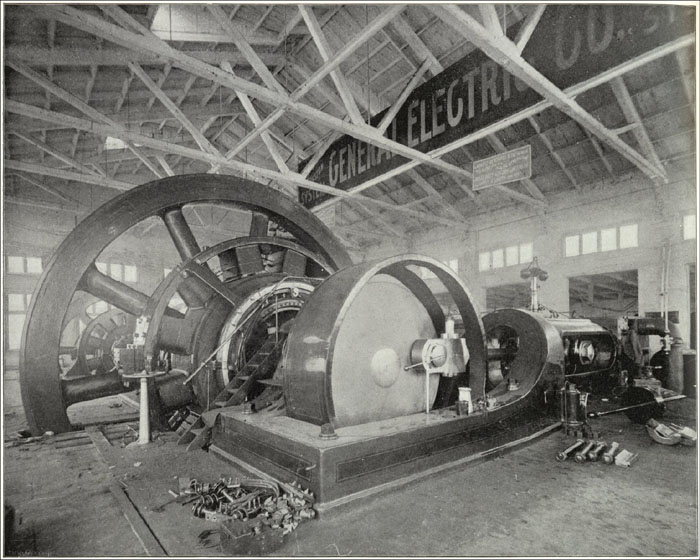

This was no mere signal. From the contact points of the key and down through the table ran wires connecting the ceremonial grandstand to Machinery Hall 1000 yards away. Without any human intervention or aid, the great fly wheel of the Allis engine was jolted into motion.

Waiting for an electric breath

Secondary only to interest in the ceremonies taking place in front of the Administration Building throughout the morning of May 1, was the attraction waiting to come to life inside in the power house south of Machinery Hall. Here, a great mass of steel and iron stood lifeless, inert, just waiting for an electric breath to fill its lungs with energy.

“Seeing the Wheels Go ’Round” from the Chicago Inter Ocean, May 2, 1893.

Surrounding the leviathan Allis engine, a crowd that would have furnished a population for a good-sized city waited for the monster to awaken. Superintendent Reynolds and Chief Engineer Lammert had everything in readiness and walked about with an air of confidence that the big old engine would perform its part of the ceremonies when the time came.

The people assembled around the great engine all expected the signal to come from the president’s hand promptly at 12:00 o’clock. When that time came and passed, there was confusion. Had there been a blunder on the platform? There was nothing to do but wait. A few minutes later, they were rewarded.

A gong sounded to announce the start of the World’s Fair. The chain belt started up, and the globe throttle valve opened. As the great piston rods began to move, the giant pully started to revolve the six-foot belt that communicated motion to the ninety-inch dynamo. In a few seconds from the time the bell rang, the steam Hercules was running at full speed.

The thrill of life seemed to possess the monster, as steam swiftly and smoothly coursed into its veins. The movements of the big Allis engine symbolized a completed and working Fair. A mighty shout went up from the crowd, and Machinery Hall was formally open to the world.

Other engines on the fairgrounds sprang to life, forcing tens of thousands of gallons of water into the fountains and cutting loose flags and banners. The mysterious currents were under ground. All that the public knew was that the Exposition was alive. Dead exhibits became imbued with life, and a flood of energy with six months’ staying power was turned loose.

“The World’s Greatest Dynamo.” [Image from Columbian Gallery: A Portfolio of Photographs of the World’s Fair (Werner Company, 1893).]

“President Cleveland Presses the Button Opening the Great Columbian Exposition” [Image from Kilburn stereoscope card 7926.]

The simple action of the president seemed to have talismanic power. It transmitted by the magic current of electricity the motion which opened the valve of the greatest of engines and breathed life into the cylinders and wheels of that monster industrial servant. The electric age was ushered into being.

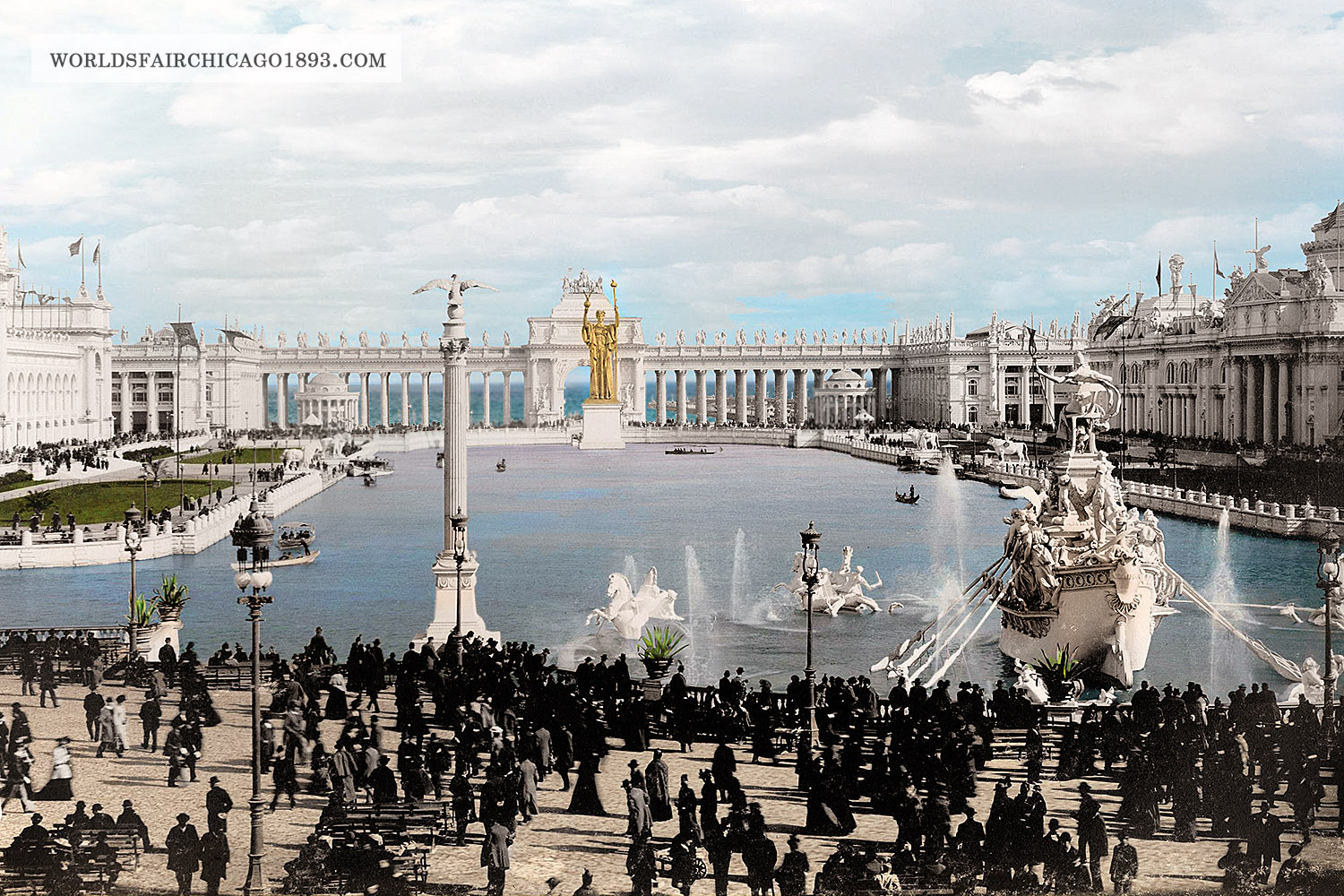

A new life was given to the Grand Basin and its surroundings, as if in obedience to a magician’s wand. No human eye could be quick enough to see the thousand manifestations of response to the momentous signal. Their appearance was absolutely synchronous.

This is what pressing of the key did …

Great fountains held crowd spellbound

… It opened the floodgates and permitted the waters to spurt from the fountains in the near foreground, filling the air with a soft mist.

Great jets of water flashed and splashed in the fountains of the central basin, sending forth silvery sprays into the sunlight.

The great MacMonnies Fountain, with its graceful figure pieces and noble design, seemed to hold part of the crowd spellbound. The rush of water was another symbol of life. Men, women, and children forgot even the subdued roar of machinery in distant buildings while listening to the miniature Niagara flowing into the basin.

A thousand umbrellas opened to protect spectators from the moisture.

“The Grand Basin” (colorized)

White palaces blazed with color

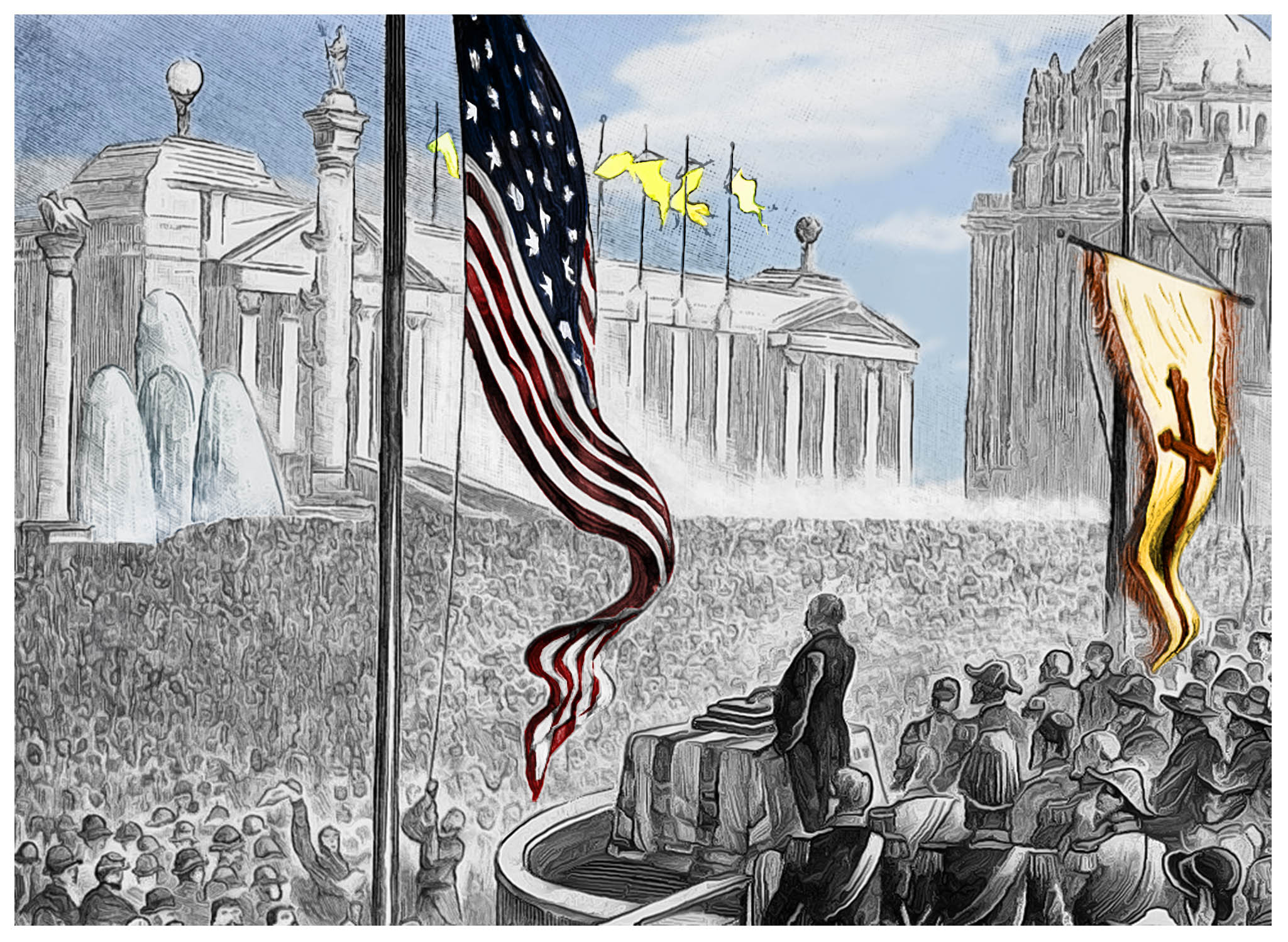

… It filled the ivory horizon with 800 flags and streamers from the roofs and towers of the surrounding palaces, as if they had all been geared to the same unfurling appliances. It blazoned the air over the heads of the multitude with the flags of Aragon and Castile, that union of Ferdinand and Isabella who dispatched Columbus to the western world.

“Unfurling of the Flags” from the Chicago Inter Ocean, May 2, 1893.

On the roofs of all the prominent buildings, hundreds of sailors perched, ready to set free the flags and banners at the proper signal. So complete were their preparations that they executed this function without a hitch. Just as the president placed his hand on the button, a young man waved his hat, triggering the release of hundreds of gay banners. Around the Court of Honor, ribbons of color fluttered as the flags and banners unfurled.

Within ten feet of the president’s face was the most impatient man in the White City, who had stood all morning at the base of the great flagstaff, eager as a boy to unfurl the colors of his country, wrapped in a small package 150 feet in the air.

When the time finally came, the white-coated sailor tugged madly at the rope that bound the mighty flag in place. With a yank, the ball of bunting streamed out, revealing the graceful folds and glorious colors of an enormous American flag. The wind swept its silken folds out over the seething mass below, who looked up to see “Old Glory” sway in a gentle breeze.

From the flagstaff at the right, the crimson and gold of Spain fluttered beneath the gorgeous caravel. At the left, the flag of the Columbus fell from the fold that bound it. The great yellow banners caught the eye and heart of the Duke of Veragua.

The cutting loose of a halyard on each pole liberated the colors. Few that saw the hundreds of flags and banners drop easily and gracefully into position realized that they were looking on a complete code of the flags of all nations. From minarets and poles, the colors of forty-seven different nations were flying.

Beautiful and variegated as were the national flags, they almost paled into insignificance beside the banners of the Exposition. Here the wealth of artistic director Francis Millet’s decorative ingenuity was seen in its real proportions.

From every tower and parapet fell and fluttered some brilliant ensign typifying the character of the exhibits inside. Gorgeous red gonfalons adorned the roof of the Manufactures Building, while ensigns of orange and white dressed the Agricultural Building. Down the long white roof line of Machinery Hall ran a sudden burst of crimson flame.

The white palaces were abloom and blazed with color. Every hue of the rainbow could be seen, from the most brilliant to the softly shaded effects that proclaimed artistic designs. The crowd did not have time, apparently, to make a critical study of the flags and banners. The effect of the sudden transformation was too great to be realized in its true proportions.

The unfurling of the immense American flag and the hoisting of the Spanish emblems on either side was the signal for redoubled efforts on the part of the enthusiastic people present. They shouted and then shouted again; they waved canes, handkerchiefs and umbrellas, and appeared never weary.

“Flags Unfurled” (colorized)

Golden colossus revealed

… It dropped the veil from the beauteous form of the golden statue of the Republic which stood looking at the unparalleled scene.”

“The Peristyle and Statue of Republic” [Image from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, May 18, 1893.]

Gondolas filled with happy parties circled around the basin, and the trim launches darted in and out by the archways under the bridges. Above the glad transformation scene, the gilded arm of the big Statue of the Republic seemed to be raised in exultant triumph.

As if to emphasize the crowning victory of peace, a flock of 200 snow-white doves set free circled over the waters of the basin. Just as they were released, a flood of sunlight burst through a bank of gray clouds. Golden gleams flashed from the Administration dome and the Statue of the Republic.

Whistles, chimes, and cannons sound

… It loosened the throats of a hundred steam whistles, and caused fire and smoke and mighty reverberations to belch from the guns in the harbor … It added the silver voices of chimes to the triumphant din.

The USS Andrew Johnson [Image from the OhioLINK Digital Resource Commons.]

The booming guns firing in the outer harbor surprised those in the vicinity of the Peristyle. Assuming some sort of explosion had occurred, many rushed in a panic to the lakefront, expecting to see the timbers of the Casino or Music Hall flying into the air.

The monstrous Krupp gun, on exhibit by Germany in its own hall along the lake shore, sat in envious silence.

“The Music Hall, The Peristyle and the Movable Sidewalk” [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair (W.B. Conkey, 1894).]

Crowd sung and cheered and cheered and sung

… It sent the echoes flying through the great city lying dark and massive in the background, and these in turn were taken up and hurled around the globe to all the nations thereof.

Deeper and more continuous than all the other sounds rose a swelling volume of human voices. At first a murmur of delight, then a roar of enthusiasm, the people cheered the transformation scene. Louder grew the volume of sound, as the pent-up enthusiasm of the multitude found expression. A hundred thousand throats swelled the paean of victory, swallowing up even the terrific crash of the cannons. Individuality was lost as the exultant throng—moved by a common impulse—sang and cheered and cheered and sang. Indians on the Administration Building balcony let forth yelps.

A performance of the “Hallelujah Chorus” from Handel’s Messiah was supposed to accompany the pressing of the key by President Cleveland. However, there simply was no room on the grandstand for the chorus of 1500.

Instead, the orchestra filled the air with “America,” the unofficial national anthem also known as “My Country ’Tis of Thee.”

Ten thousand voices in the vicinity of the grandstand caught the refrain. The swelling notes of “America” kindly offered the opportunity craved by those who do not shout and who do not give way to orderless ecstasy, to participate understandingly in the universal manifestation of joy. Even President Cleveland joined for a moment his voice to the mighty volume of sound sweeping across the basin and out to the lake. He lost none of his dignity when he joined his fellow citizens in that grand hymn.

Then, from down in the lagoon, more patriotic voices took up the stirring song. As inexhaustible inspiration flowed through the air without check or pause, people stood riveted, bathed in the sound as in an element. Men and women felt ready to melt into these harmonious yet turbulent waves and float away towards eternity upon the tides of the music. No hymn of praise or victory was ever more heartfelt. Patriotism was incarnate, and emotion shook the multitude. The moment was sacred.

Pomp, position, aspiration, ambition, all faded away in that combined individual realization of unselfish love of nation.

“Three cheers for Grover!” shouted 10,000 voices, and once more 200,000 human beings lifted their voices in salute to the president of the republic.

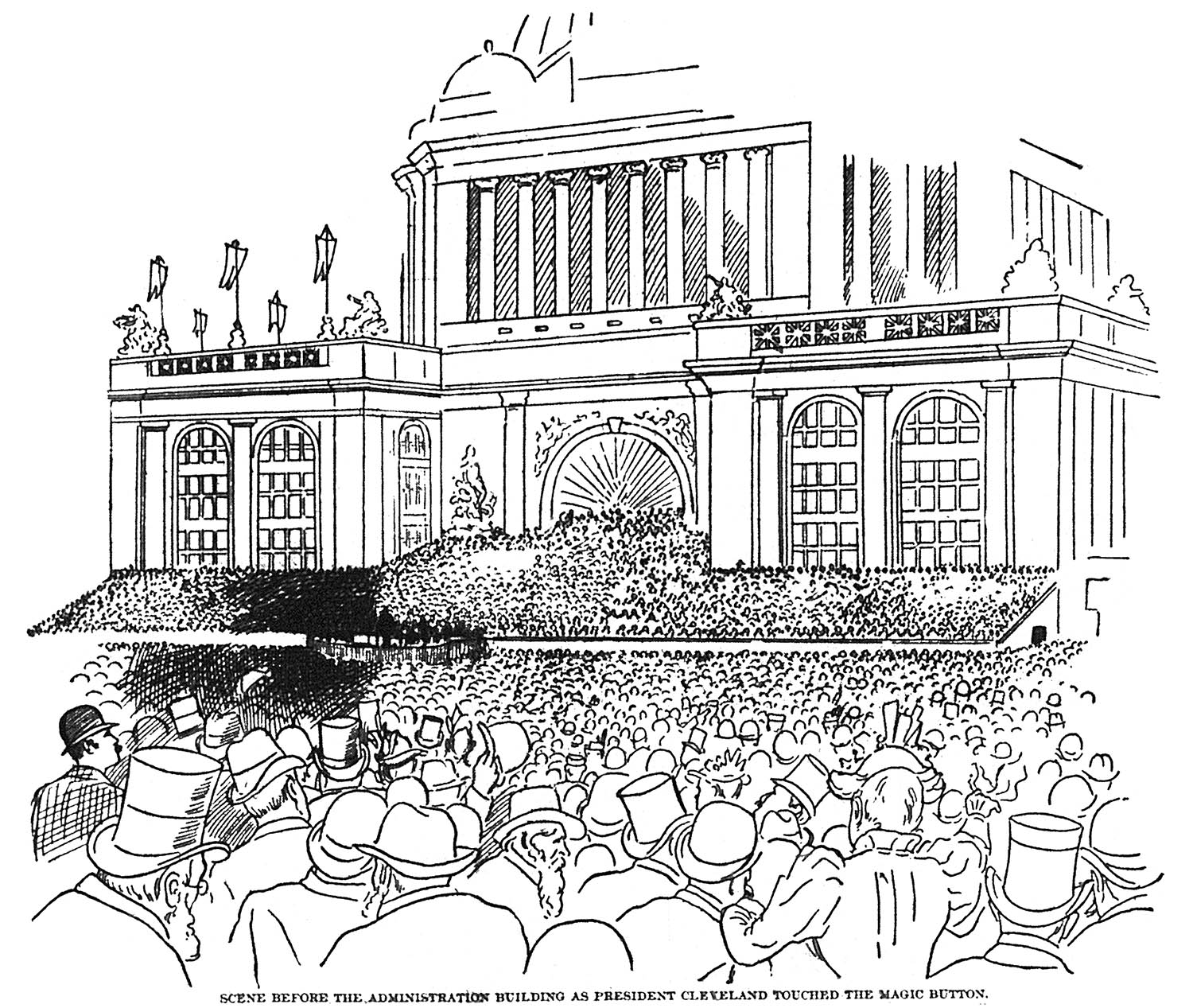

“Looking South Across Plaza East of Administration Building the Moment the President Touched the Button” [Image from Harper’s Weekly, May 6, 1893.]

The moment of moments

The overall effect of the sudden unfurling of the flags and the starting of the machinery was grand, and the enthusiasm of the assembled multitude unbounded. The conclusion of the Opening Ceremony was the most beautiful spectacle which man has ever created to please his own sensibilities or satisfy his vanity. It was not only the supreme moment in the history of the land and the west, but the moment of moments in the lives of a vast majority of the beholders.

The Exposition was open!

“Scene Before the Administration Building as President Cleveland Touched the Magic Button” from the Chicago Inter Ocean, May 2, 1893.

SOURCES

(See our note about sources here.)

“Cleveland Presses the Golden Key” Salt Lake Herald May 2, 1893, p. 1.

Dedicatory and Opening Ceremonies of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Stone, Kastler & Painter, 1893, p. 259.

“Engine Starts with no Difficulty” Chicago Daily Tribune May 2, 1893, p. 3.

“Epoch in History” Chicago Herald May 2, 1893, p. 1.

“Formally Opened” Chicago Inter Ocean May 2, 1893, p. 5.

“How Grover Hammered the Key” Chicago Herald May 2, 1893, p. 2.

“Hundreds of Thousands There” Chicago Herald May 2, 1893, p. 2.

“In the Grand Stand” Chicago Daily Tribune May 2, 1893, p. 1.

“Leading Articles of the Month” Review of Reviews June 1893, p. 603.

“Music Admirable and Effective” Chicago Daily Tribune May 2, 1893, p. 1.

“Opened to the World” Chicago Eagle May 5, 1893, p. 6.

“Opening Ceremonies World’s Columbian Exposition” in Columbian Exposition Dedication Ceremonies Memorial. Metropolitan Art Engraving & Publishing Company, 1893, pp. 212-224.

“Our Day of Triumph” Chicago Inter Ocean May 2, 1893, p. 1.

Pickett, Montgomery Breckinridge “Opening of the Great Fair” Harper’s Weekly May 13, 1893, p. 442.

“Ready for a World” Chicago Daily Tribune May 2, 1893, p. 1.

“Spring Into Being” Chicago Daily Tribune May 2, 1893, p. 3.

“Starting the Engines” Chicago Inter Ocean May 2, 1893, p. 2.

“Starting the Machinery” New York Tribune May 2, 1893, p. 11.

“The Great Fair Opens” Current Literature June 1893, p. 138-142.

“The World’s Columbian Exposition” Harper’s Weekly May 13, 1893, p. 2.

“Were There to See” Chicago Inter Ocean May 2, 1893, p. 2.

“Viewed from Above” Chicago Daily Tribune May 2, 1893, p. 5.

“‘White City’ Half in Cloud Land” Chicago Daily Tribune May 2, 1893, p. 1.

Leave A Comment