Without the flag, there would be no Flag Day. And without Betsy Ross, there would be no flag (or so the story goes). Among abundance of eye-catching exhibits inside the Agricultural Building of the 1893 World’s Fair stood a unusual sculpture of the purported mother of the American flag.

The Agricultural Building housed many wonderous exhibits of the varied output of farms and the amazing products of a burgeoning agriculture industry. Visitors could encounter the likeness of Betsy Ross in the gallery level. [Image from Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume II. M. Juul & Co., 1894.]

Flag Day at the Fair

At the time of the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, the idea for an annual celebration of the Stars and Stripes on June 14 was only a few years old, and not yet widely adopted. As the White City on Lake Michigan was rising, so was interest in the national colors. To coincide with Dedication Day on the Chicago fairgrounds, Congress proclaimed October 21, 1892, as a National Columbian Public School Celebration. For the event, a Christian Socialist working for the Youth’s Companion composed the “Pledge of Allegiance.” Schoolchildren across the country recited in unison Francis Bellamy’s simple verse:

“I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

Eight months later, Flag Day went largely unnoticed at the World’s Fair. On June 14, 1893, Chicago was busily attending to the departure of the Infanta Eulalia of Spain in the morning and preparing for “German Day” to be held at the Fair the following day. While Philadelphia and some other cities held major Flag Day events in 1893, Chicago inaugurated its large Flag Day celebrations across the city in June of 1894.

Two years after the 1893 World’s Fair, Flag Day had become a bigger event. This cartoon about the leading events of the week on the front page of the June 16, 1895, Chicago Tribune includes a depiction of the “National Celebration of Flag Day” with Columbia and Old Glory.

“Brought to their attention in the most striking manner”

Allegiance to a flag, however, did not necessarily mean familiarity with the history of the emblem. “Thousands of people who go to the World’s Fair, knowing little, or maybe nothing, of the history of the national flag or of the woman who made the first one …” recorded the Philadelphia Times, “will have the matter brought to their attention in the most striking manner by the statue of Betsy Ross in the northeast corner of the gallery of the Agricultural Building.” The goal of one public-spirited citizen from Philadelphia was to help make the name of Betsy Ross “a household word in the mouths of the American people.” To do this, Mr. William Dreydoppel was determined that a statue of the then-not-so-famous seamstress should be erected somewhere it could be seen by millions—at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

While Mr. Dreydoppel’s patriotic message (though of questionable historical accuracy) hewed closely to traditions, the medium he chose for the Betsy Ross statue certainly did not.

An 1892 advertisement for Dreydoppel Soap showing the company founder. [Image from the Philadelphia Inquirer Mar. 3, 1892.]

“Sagacity, industry, good judgment and integrity”

Born in April 1833, in Neuwied on the Rhine, William Dreydoppel came to the United States on October 16, 1860. Not long after arriving in New York, the new immigrant enlisted in the Union Army. After serving in the Civil War, he moved to Philadelphia where he started the Dreydoppel Soap Works in 1867 and became “one of the most prominent business men of Philadelphia.” Mr. Dreydoppel, who reportedly had a strong resemblance to Germany’s “Iron Chancellor” Otto von Bismarck, built his soap empire using “sagacity, industry, good judgment and integrity.” His success earned him recognition at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia and again at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris. As he contemplated his company’s exhibit for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, his thoughts turned to a fitting tribute to his adopted city and country—the “Mother of the Flag.”

The Betsy Ross House at 239 Arch Street in Philadelphia was becoming a tourist attraction by 1893. [Image from the Harrisburg (PA) Telegraph Jun. 14, 1893.]

“A beloved national myth”

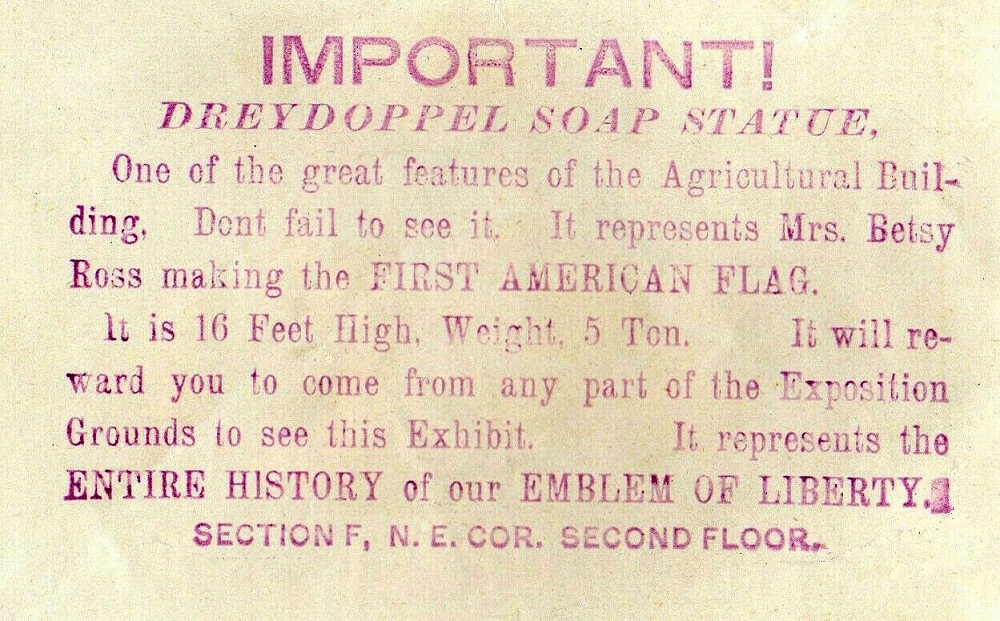

If visitors to the 1893 World’s Fair did not know about the prominent early American flag maker, then Mr. Dreydoppel would create an unforgettable advertising display for his exhibition booth, using an image of Betsy Ross that “represents the entire history of our emblem of liberty,” according to his advertising.

Historians today recognize that Elizabeth Griscom Ross (1752–1836), the seamstress better known as Betsy, has a tenuous association with the history of the first United States flag. “Although a beloved national myth holds that the Philadelphia upholsterer helped design and stitch the emblem of the United States,” writes Erin Blakemore in National Geographic, “Ross’s involvement in the history of the American flag is widely regarded as apocryphal.” The Smithsonian National Postal Museum also asserts that “while many Americans still believe that Betsy Ross was responsible for the first American flag, and while it makes for a nice story, sadly, it is most likely false.” Inviting visitors to ask “Did She or Didn’t She?”, the Betsy Ross House offers that “whether you choose to believe Betsy Ross made the first flag, there is no doubt that she was a prominent early American flag maker who stitched flags for the federal government for more than 50 years.”

In 1893, the legend of the early American flag maker was still forming. “The name of Mrs. Betsy Ross, of Philadelphia, like that of many others who played their part in helping to shape the future of the young Republic, has never been blazoned on the temple of fame,” observed the Philadelphia Inquirer, which recognized the provincial nature of the story:

“It may be questioned if, outside of Philadelphia, where she lived and died, there are many people except students of history who could tell what she did that her name should be remembered, and yet whenever the Stars and Stripes are seen waving in the breeze the fluttering folds should call up to recollection the bravo and patriotic woman whose deft and patient fingers plied the needle and wrought the first flag that told to the world the birth of liberty.”

Mr. Dreydoppel wanted to change that and would spend more than $5,000 (around $175,000 today) on a sculpture of Betsy Ross. “Realizing that the name of the once highly esteemed townswoman was, in the West especially, but little known,” the Inquirer continued, he was “determined to bring it to the minds of the American people in a manner they would not soon forget.” To create this unforgettable sculptural display, the Philadelphia businessman hired an artist from his city who was also establishing the flag’s origin story in the medium of paint.

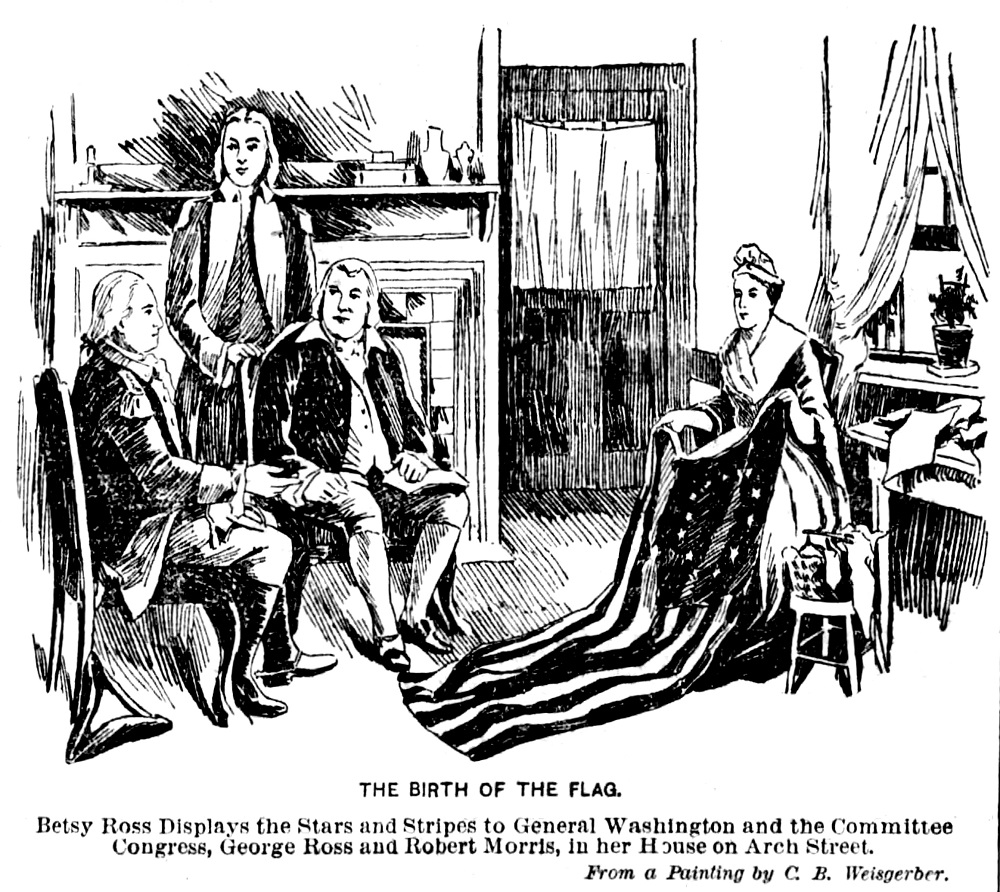

The monumental painting depicting The Birth of Our Nation’s Flag by Charles H. Weisgerber was on display inside the Pennsylvania State Building at the 1893 World’s Fair. [Image from the Philadelphia Times, June 14, 1893.]

The Birth of Our Nation’s Flag

Charles H. Weisgerber (1856–1932) was at work in 1892 and 1893 on a monumental canvas showing a scene of the Quaker seamstress displaying the original national colors. His 9-by-12-foot painting titled The Birth of Our Nation’s Flag depicts Betsy Ross showing her hand-made flag to Gen. George Washington, George Ross, and Robert Morris on June 14th, 1777. To aid his painting, Weisgerber reportedly used an old daguerreotype of Mrs. Ross that was “provided by a direct descendant, Mr. Crosby of Philadelphia.” (This may have been William J. Canby, a grandson of Mrs. Ross, who in 1870 recounted his family story at the Pennsylvania Historical Society and spent the subsequent decades tirelessly promoting Ross’s place in American history.) Weisgerber appears to have completed the painting by April 1893. The huge canvas made its way to Chicago and went on display inside the Pennsylvania State Building.

For his pavilion in the Agricultural Building, Dreydoppel wanted Weisgerber to bring Betsy Ross to life in three dimensions and to promote his company’s product. They devised an ingenious advertising campaign—Betsy Ross in soap! “Neither marble nor bronze was decided upon as the material to be used by the sculptor, but pure Dreydoppel soap,” reported the Philadelphia Inquirer, “a saponified material which has readily lent itself to the sculptor’s chisel, and has shown itself to be possessed of more lasting qualities than would at first have been believed.” While most sculptors used staff (a mix of plaster and fiber) to create their temporary works for the Exposition, Weisgerber employed a much softer, and water-soluble, substance. His soap statue would need to survive sculpting, moving, and six months standing in the Chicago heat.

Sculpting a non-traditional material had precedence at this and previous expositions. Chocolatiers Maillard’s and Stollwerck each were preparing showstopper chocolate statues in 1893 for their pavilions in the Agricultural Building. At the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Arkansas housewife Caroline Brooks had sculpted Dreaming Iolanthe from butter. Considering this evolution in art media prompted the Wilmington (DE) Morning News to quip that “from butter to soap is not a very considerable stride in 17 years.”

Indeed, Dreydoppel was not the only firm to showcase a soap sculpture at the 1893 World’s Fair. In the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, the booth of Kirk’s Soap of Chicago displayed “an imitation in soap of Brooklyn Bridge, some thirty feet long and weighing 1,500 pounds,” records historian Hubert Bancroft, “with vehicles and pedestrians crossing in long procession, and beneath a vessel plowing the waters of East River.” Elsewhere, the pavilion of the Sunlight Soap Company of England was topped with a model of Windsor Castle, forty feet long and twenty inches in height, crafted from their soap.

Mr. Weisgerber reportedly spent six months on Dreydoppel’s soap sculpture. If true, then he would have begun sculpting his Betsy Ross monument no later than October of 1892, and his work likely would have overlapped his painting of The Birth of Our Nation’s Flag. He completed most of the chiseling in Philadelphia and then sent the various sections of the statue to Chicago, where it arrived in the fairgrounds on April 10. The artist then spent another three weeks busily fitting together the many blocks of soap to reconstruct the statue and its adjuncts. He completed his work before May 1st Opening Day of the Exposition, formally turning over the sculpture to Mr. William Dreydoppel, Jr., who was it charge of the booth. Although many other exhibits across the fairgrounds still were unfinished on Opening Day, the “beautiful and strikingly picturesque figure” of Betsy Ross proudly greeted visitors inside the Agricultural Building.

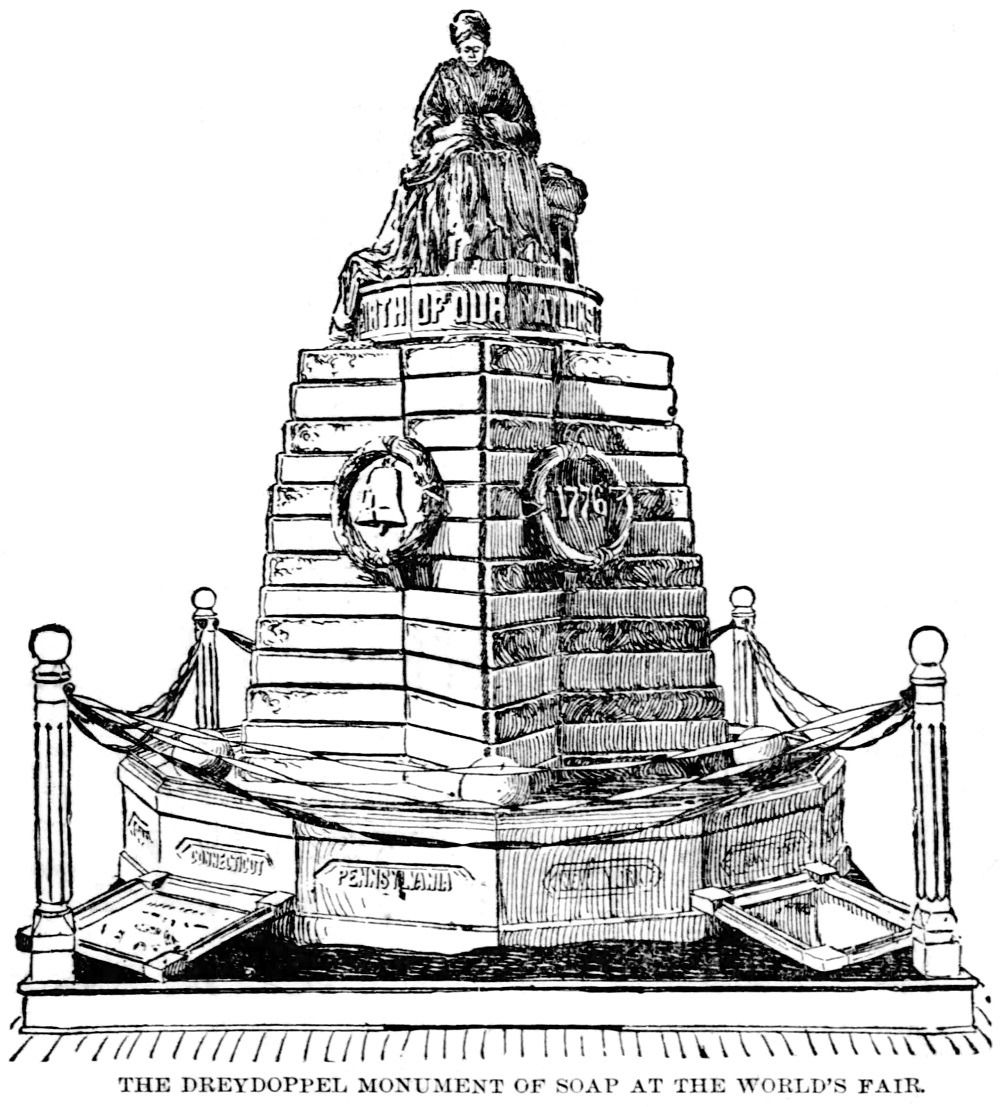

The sixteen-foot-tall Dreydoppel monument of Betsy Ross in soap. [Image from the Philadelphia Inquirer July 9, 1893.]

“A decidedly unique exhibit”

While many American soap companies displayed their products in the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, others, including William Dreydoppel of Philadelphia, exhibited with the Agriculture Department’s Group 19: Fats, oils, soaps, candles. The Dreydoppel Soap Company booth could be found in the northeast corner of the gallery level. Also in the gallery were striking exhibits, such as a mammoth flour barrel complete with a soon-to-iconic advertising persona flipping pancakes from the R. T. Davis Mill Company and the H. J. Heinz Company pavilion (though apparently not a much-talked-about pickle map of the United States).

Red, white, and blue ribbons festooned the four white posts marking the corners of the Dreydoppel booth, and a banner in the national colors and the words “Dreydoppel Soap” in gilt letters surmounting each. The diplomas that had been awarded to Dreydoppel Soap at the 1876 and 1889 expositions were on display, under glass in frames made of—you guessed it—soap.

Under a canopy of red, white, and blue bunting stood the showstopper Betsy Ross statue. The soap sculpture stood an imposing sixteen feet high and weighed five tons. A circular base, about two feet high, was composed of thirteen slabs of soap, each with a rectangular plate inscribed with the name of one of the thirteen original colonies.

Rising from the base was a tall, pyramidal pedestal in the form of a five-pointed star, representing the star shape that (according to tradition) Mrs. Ross proposed for the American flag design. Sitting at the foot of each point was a cannon ball in soap. The recessed angles of this star-shaped pedestal were adorned with five wreathed plates. Four were inscribed with the years of great wars of the country—1776, 1812, 1846, and 1861—while the fifth bore an image of the Liberty Bell, which at that time was on display in the Pennsylvania State Building. Surmounting the pedestal, a circular plinth carried the message “The Birth of Our Nation’s Flag,” clearly drawing attention to the artists’ painting also in that building.

Seated on the pedestal was the figure of Betsy Ross in the act of making the first flag of the United States. The Philadelphia Inquirer offered this description:

“The artist has represented Betsy Ross sitting in an old-fashioned, highbacked arm chair sewing the American flag, with a stool by her side on which she has evidently sketched the design. Her scissors hang from her right side, while the folds of the flag fall gracefully from her hands over the pedestal. The expression of the face is serious and gentle. The wavy hair is parted in the centre and smoothed down in the old fashion on either side of the forehead and then fastened in a knot at the back. The head is adorned with a lace cap, and the dress is in the style worn by colonial dames, the sleeves falling just below the elbow.”

The Honolulu Star-Bulletin characterized the countenance of Mrs. Ross as “lovable, with that peaceful sweetness so common in the faces of the Friends.”

“Don’t fail to see it,” Dreydoppel urged fairgoers in his company’s advertising. [Image from “Light and Shade” pamphlet; private collection.]

“One of the most peculiar and most popular exhibits”

Periodicals described the soap sculpture as “one of the most peculiar and most popular exhibits in the World’s Fair” and “a decidedly unique exhibit,” and praised “the romantic story connected with it, and the beauty and originality of the design, all tending to make it widely admired.” Dreydoppel’s own advertisements claimed his Betsy Ross to be “one of the great features of the Agricultural Building.” His hometown newspaper thought that the attraction would “draw to it every visitor, whether they be patriotic citizens or merely lovers of what is beautiful and original,” and wrote of “a constant attraction to visitors from all States and countries.”

The display did not lather as expected. Being relegated to a remote location in the corner of the gallery, and having stiff competition from huge chocolate statues, a giant flour barrel, and a mammoth wheel of cheddar, the Betsy Ross in soap failed to garner the attention it deserved. Relatively few newspaper reports or visitor accounts mention it, and no photos of the display seem to survive.

However, Mr. William I. Buchanan, chief of the Department of Agriculture, reportedly took great interest in the statue and regretted that it was not placed in a more prominent position. Moving and reassembling it somewhere on the first floor of the building, he said, would have required far too much labor. Still, Mr. Buchanan was “anxious to have every citizen of the United States view the exhibit, as he thinks the patriotism shown in it is worthy of notice by the whole country.”

Within a few weeks of receiving first prize at the 1893 World’s Fair, Dreydoppel Soap boasted about the award in their advertising. [Image from the Camden (DE) Post, Oct. 18, 1893.]

Down the drain

William Dreydoppel received a telegram on October 1 notifying him that the Exposition had awarded him first prize for his soaps, and he soon used the award in advertising campaigns. Despite the summer heat in Chicago, which partially melted chocolate sculptures elsewhere in the Agricultural Building, the soap statue seemed to retain its shape. Even by July, Dreydoppel reportedly had fielded numerous inquiries about placing his statue on exhibition in some Eastern cities after the Fair closed. At least one news outlet proposed that the soap statue of Betsy Ross was a work of art worthy “of reproduction in permanent material.” No such casting was made, however, and the soap statue seems to have dissolved after the Exposition closed on October 30.

With or without the help of the 1893 soap statue, Betsy Ross’s reputation as the mother of the American flag continued to grow in the years after the Columbian Exposition. That certainly would have pleased William Dreydoppel. The soap maker died in his Philadelphia home on March 5, 1906, and is buried in Mount Peace Cemetery in that city. Though ephemeral, the soap sculpture he sponsored at the 1893 World’s Fair is a rare example of a statue of Betsy Ross.

SOURCES

Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.

“Betsy Ross, Maker of the Flag” Philadelphia Inquirer Jul. 9, 1893, p. 15.

“A Butter Woman” Wilmington (DE) Morning News Jul. 8, 1893, p. 4.

“Columbian Exposition” American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record Jul. 27, 1893, p. 63.

“William Dreydoppel” Soap Gazette and Perfumer Apr. 1, 1906, p. 124.

“Light and Shade” Dreydoppel Soap pamphlet, c1892. [Note: This sixteen-page advertising booklet contains a racist fantasy about skin color and cleanliness, with the message “An American soap for American people!” The comic strip with verse describes a boy who “wished to change from black to white” and so used Dreydoppel Soap to lighten his skin until “his face was as white as white could be.”]

“A Philadelphian Takes First Prize” Philadelphia Times Oct. 2, 1893, p. 2.

“A Statue of Betsy Ross” Philadelphia Times Jul. 3, 1893, p. 2.

“Statue in Soap” Honolulu (HI) Daily Bulletin Aug. 19, 1893, p. 4.

Leave A Comment