Chicago is abuzz about “Myth and Marble,” a fabulous new exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago running from March 15 to June 29, 2025. On display are fifty-eight magnificent sculptures of gods and goddesses, emperors and funerary monuments. All come from the Torlonia Collection of Rome, one of the world’s finest private collections of Greco-Roman antiquities. The artwork has been out of the public view for most of the past century.

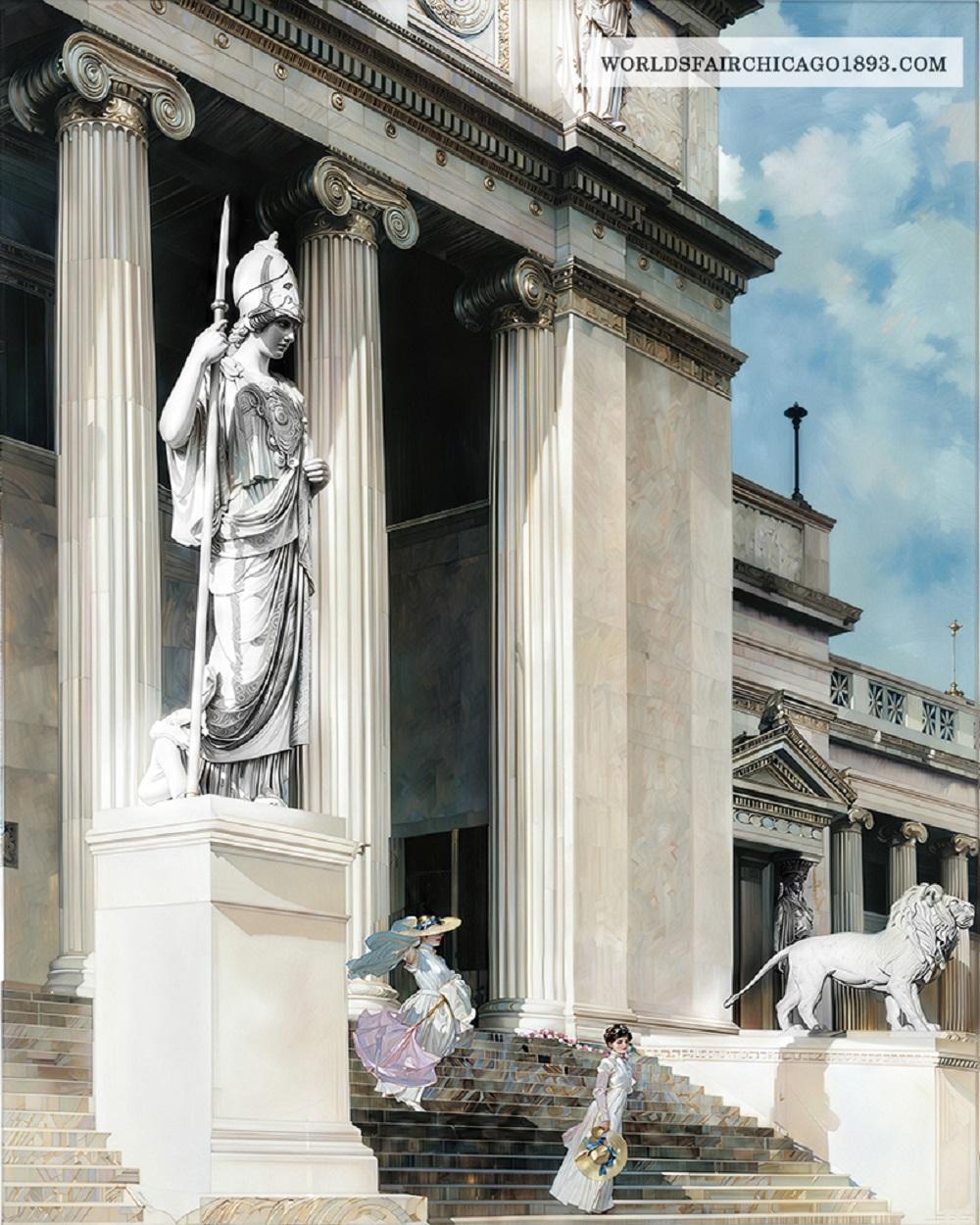

Statue of Athena from the Torlonia Collection of Rome, on display in “Myth and Marble.” [Photo from worldsfairchicago1893.com.]

A scene showing Minerva in front of the South Porch of the Palace of Fine Arts at the 1893 World’s Fair. [Image digitally created and © worldsfairchicago1893.com]

The Goddess of Wisdom at the 1893 World’s Fair

These two sculptures have arrived in Chicago 132 years after a notable earlier statue of this goddess went on display on the grounds of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Standing guard at the South Porch of the Palace of Fine Arts was an eighteen-foot-tall sculpture titled Minerva. In Roman mythology Minerva was the daughter of Jupiter and the Goddess of Wisdom and the Liberal Arts and also the Goddess of War. Romans equated her with the Greek goddess Athena. Athena/Minerva typically is represented with flowing draperies, armed with shield and spear, and wearing a helmet and the Aegis on her breast.

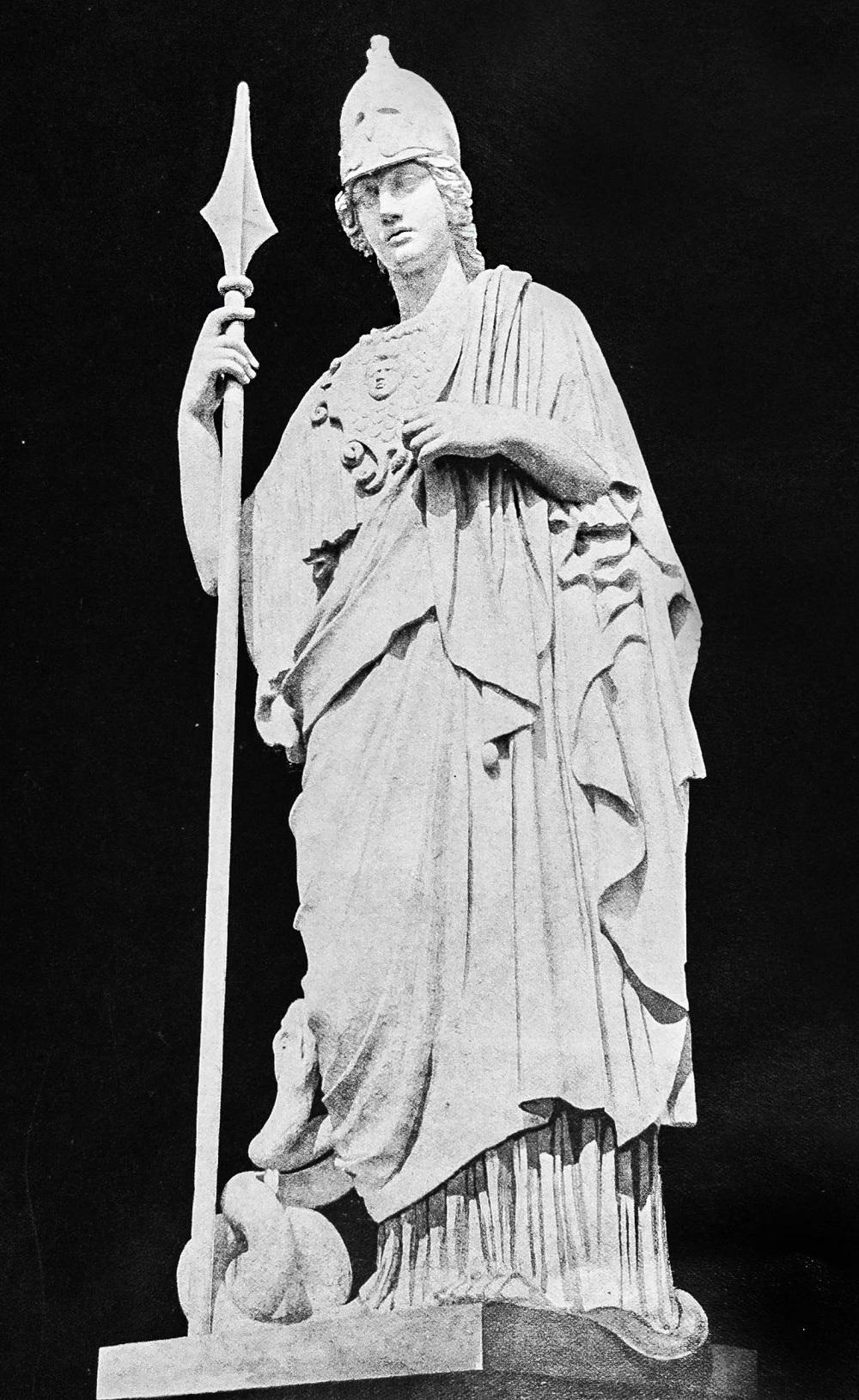

The statue of Minerva from the 1893 World’s Fair. [Image from Art Treasures from the World’s Fair. The Werner Company, 1895.]

Art Treasures from the World’s Fair describes the subject and history of the sculpture in caption text for an accompanying photograph (shown above):

MINERVA GIUSTINIANI—This stately figure of the Goddess of Wisdom stood at the south entrance of the Art Palace. It represents her fully draped, as indeed was customary in all statues of this goddess, wearing the breastplate, on which was the head of Medusa, and the helmet surmounted by a griffin. She leans meditatively upon her spear, and at her feet is coiled a serpent, which was considered sacred to her, as the emblem of vigilance and health. The original statue was supposed to be a Roman copy of an older Greek work made about 50 B.C. It was found close by the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome; which church, as may be gathered from its name, was built over the ruins of a temple of Minerva. The date of its discovery is unknown, but in the beginning of the 17th century it was in the possession of the noble Giustiniani family from whom it passed to Lucien Bonaparte; of him Pope Pius VII bought it, and placed it in the Vatican, where it now is. The statue when found was very nearly perfect. There has been restored only the right forearm and hand holding the spear, and the fingers of the left hand. The face of the goddess is of a beautiful and thoughtful type, less sensuous than that commonly given to Venus. She stood dignified and benign, welcoming thousands to the Fair as they approached that superb Grecian temple of art, which might almost be called the temple of wisdom.” [Art Treasures 53]

The Myth of Marble

Except for the comment of “where it now is,” this description makes no explicit statement that the sculpture at the Chicago fair was a reproduction. Like nearly all the sculptural works on the fairgrounds, it was made of staff (a stucco-like material made from plaster and jute fiber) and intended as a temporary decoration. Unlike other featured sculptures, its creator remains unidentified.

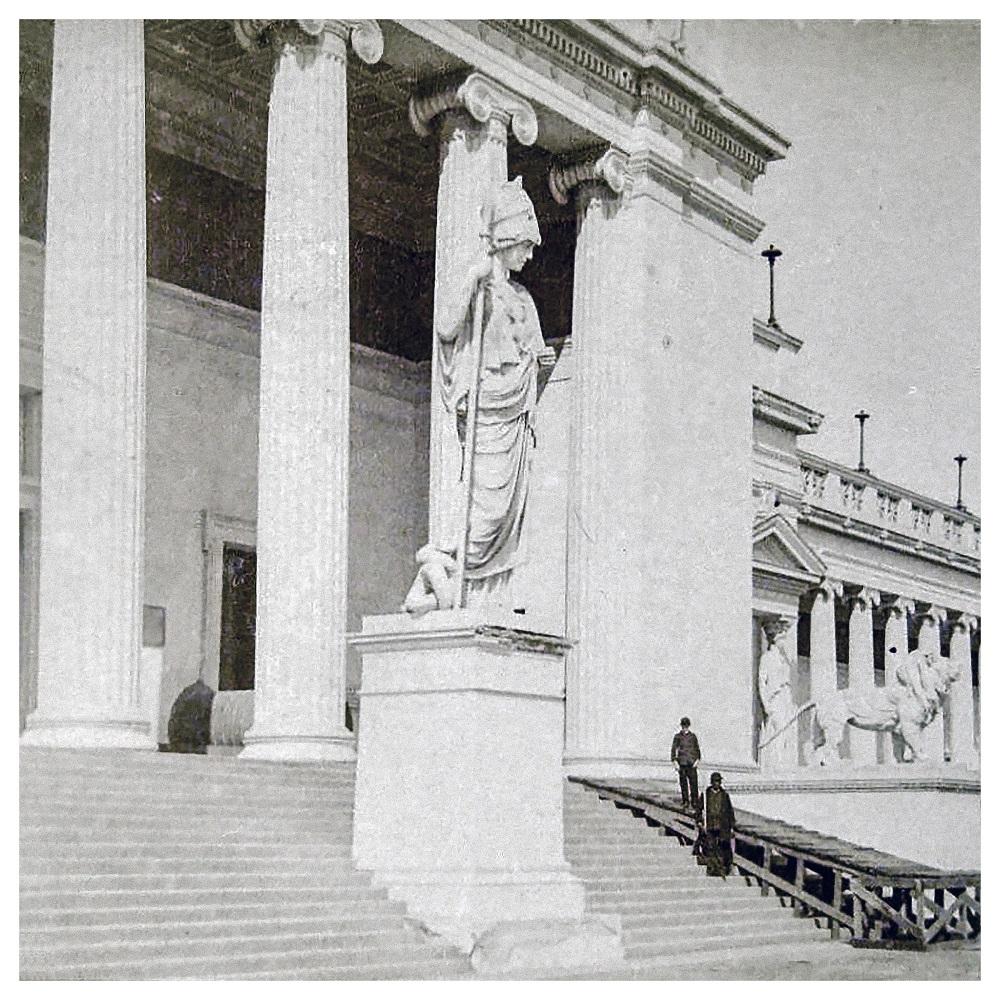

A side view of the statue of Minerva at the south entrance to the Palace of Fine Arts. [Image from Underwood & Underwood stereoscope card “Entrance to the Art Palace, World’s Columbian Exposition.”]

Minerva Giustiniani

This eighteen-foot-tall staff Minerva and the accompanying Caesar on the other side of the building were enlarged reproductions of Roman marble sculptures in the collection of the Vatican Museums. Previously in the collection of Vincenzo Giustiniani, the so-called Athena Giustiniani or Minerva Giustiniani stands about seven-and-a-half feet tall. (The Torlonia’s Statue of Athena in the current “Myth and Marble” exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago also came from the Giustiniani Collection.)

In his report to Director of Works Daniel Burnham, Superintendent of Buildings W. D. Richardson refers to the statues alternately as “Minerva and Caesar” and “Minerva Medica and Augustus.” Although the person who selected these two particular Roman statues for the Exposition is not recorded, Richardson notes that they were made by (unnamed) sculptors employed by the Department of Grounds and Buildings using models received from the Art Institute of Chicago. His use of the title Minerva Medica comes from one tradition of the statue’s discovery, which holds that it was recovered from ruins on the Esquiline Hill which then became known as the “Temple of Minerva Medica.” As they welcomed guests into the Palace of Fine Arts, the two reproductions of ancient statues held a unique position among the constellation of new sculptural works around them. “The almost purely Grecian architecture of this building needs but little sculptural ornamentation,” Richardson writes, “but all must agree that what is there is in perfect harmony with the classic tone.” [Burnham, 39]

The marble Athena Giustiniani or Minerva Giustiniani in the collection of the Vatican Museums. [Image from Wikipedia.]

Minerva steps down

Minerva came down from her pedestal some time after the 1893 World’s Fair closed. While many of the staff sculptures from the Exposition found a new home inside the former Palace of Fine Art building when it opened as the Field Columbian Museum, including seventy statues in the Columbian Rotunda, Minerva does not appear to be among them. Photographs of the opening day ceremony of the Field Museum on June 2, 1894, show that the statue of Caesar remained standing on the north side of the building.

New reproductions of the Goddess of Wisdom made some guest appearances at subsequent world’s fairs, when staff copies of Minerva Giustiniani were exhibited at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo and the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis.

A photograph of the south façade of the Field Columbian Museum circa 1901 shows that the staff lion sculptures by A. Phimister Proctor remained standing while the Minerva statue is gone. [Image (cropped) from a Detroit Photographic Co. postcard in the collection of the Library of Congress.]

SOURCES

Art Treasures from the World’s Fair. The Werner Company, 1895.

Burnham, Daniel H. Final Official Report of the Director of Works of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Garland Pub., 1989.

Robinson, Charles Mulford “The Fair as a Spectacle” in Rossiter Johnson A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Held in Chicago in 1893, Volume 1: Narrative. D. Appleton and Co., 1897, pp. 493–512.

Leave A Comment