The pair of lions sculptures by Edward Kemeys that guard the entrance to the Art Institute of Chicago are among the most recognized icons of the city. Their confusing origin story, often incorrectly connected to the 1893 World’s Fair, is described in Part 1 and Part 2 of “Did the Art Institute of Chicago lions come from the 1893 World’s Fair?”

A profile of Edward Kemeys, written when his lion sculptures were about to be cast in bronze and published in the Chicago Record on September 25, 1893, is reprinted below.

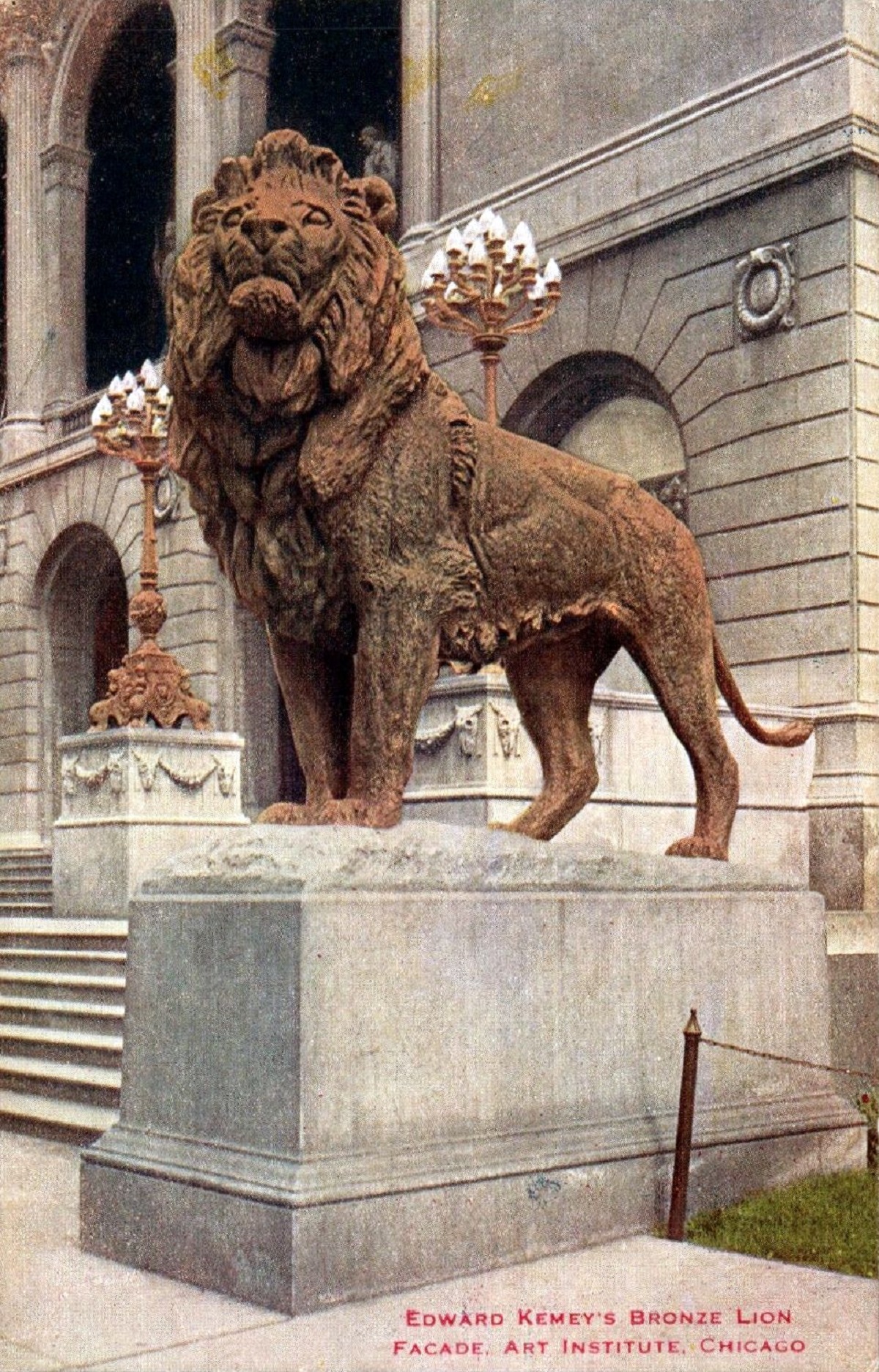

When installed in 1894, the Art Institute lions were bronze colored. [Image from a postcard by the V. O. Hammon Publishing Company c1915.]

KEMEYS AND HIS WORK

SKETCH OF A SCULPTOR

How He Roved the Plains Restless and Dissatisfied, Unconsciously Fitting Himself for His Art—The Lions for the Art Institute

At the foundry at Grand Crossing [1] are two huge lions in staff which are soon to be cast in bronze. They are destined to adorn the Art Institute. When finished they will be placed on the two pedestals on either side of the main entrance. They are the work of Edward Kemeys, and were presented by Mrs. Thomas Nelson Page.[2] They are of gigantic proportions, much larger than any of the specimens of the animals seen in captivity. The spirit of the pose in each is of an entirely different nature. In one the lion is shown creeping stealthily along, his head depressed as well forward, his eyes fixed and his ears pricked up as if on the trail of his prey. The other lion stands in an attitude of defiance as if regarding some object at a distance.[3] The pose is one of great dignity and power. The head is raised to its full height and the mane seems to bristle with rage. Speaking of this pose, the artist said: “It is one of the most difficult I have ever attempted, as lions in captivity never raise their heads above the level of their bodies. It is only in their native jungles when detecting some far-off danger that they take this pose. I have, therefore, only seen it on one or two occasions.”

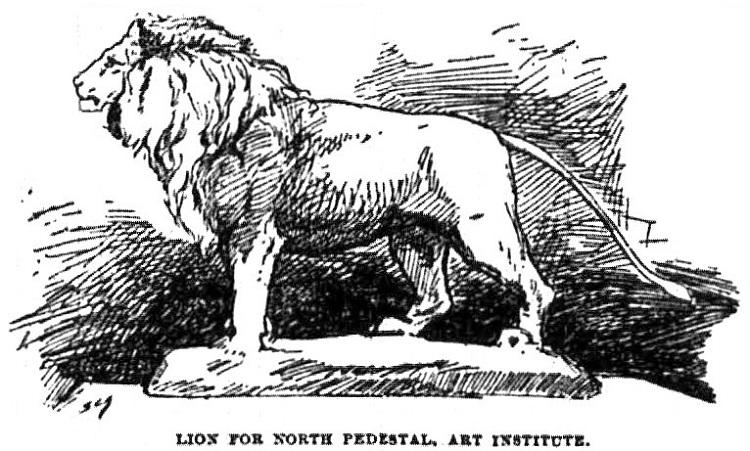

Edward Kemeys’ lion for the pedestal north of the entrance to the Art Institute of Chicago is “on the prowl.”

Edward Kemeys’ lion for the pedestal south of the entrance to the Art Institute of Chicago “stands in an attitude of defiance.”

How Mr. Kemeys Became a Sculptor

Mr. Kemeys depends entirely upon inspiration for the suggestion of all his groups and their posing. He tells the most interesting story of the conditions leading up to his becoming a sculptor, and while he seems utterly oblivious to any such phenomena as the force of psychic suggestion, the devotees of that occult science would doubtless regard him as a glowing example of its truth. Mr. Kemeys started out in life not in any way surrounded by or adjacent to any so-called school of art. He was a hunter and trapper. For years he wandered up and down the prairies of the west, sleeping at night on the open prairie or in some frontier hut, with nothing but the almost human cry of the catamount or the howl of wolves to keep his company. In the winter he went into the mountains killing and trapping wild animals of every description, thus familiarizing himself with the habits and anatomy of the animals by the natural method. His first conceptions of a panther were suggested by seeing it ready to spring at its prey. This bit of personal experience is cast in bronze in the Still Hunt, which adorns Central Park, New York.[4] It has made the sculptor famous.

Of the buffalo he was a tireless hunter. He saw the animals when they rushed in a mad stampede across the prairie and when in a gentler mood they stood in groups as the evening shadows closed in around them.

His First Prize in the Salon

It was one of these groups which Mr. Kemeys selected as his subject when he went to Paris, entirely unknown and unheralded, and succeeded in getting a medal from the salon in 1879. He went there secretly, rented a studio, worked out his group of buffalo, sent it to the salon and waited. It was placed fourth and received a medal.

“I always had a passion for animals,” he said. “In hunting it was not simply to kill that interested me. When I shot an animal, a bear, a deer or a panther, I invariably used to handle it while it was yet warm; to pose it in different attitudes and afterward to skin and dissect it.”

Mr. Kemeys made friends with the Indians. He drew pictures for them and played on an old banjo, which was his invariable companion. For months together he was “snowed in” among them. He learned their language and habits. The Crows, who have always been considered particularly fierce, were his especial friends, and he has written a volume about them, which, however, he has never published. In all of these wanderings Mr. Kemeys says that he had particular fits of depression or melancholia—an unrest, or a longing for something that seemed always just escaping him. In those days it was not quite clear to him whether the restlessness caused his wanderings or whether the wandering caused his restlessness. Finally he drifted east and became engaged with some civil engineers, who were then working on Central Park.

The Prophetic Accident

One day he saw an old German working out some figures in clay. A wolf’s head was the particular object in hand. Instantly he was seized by a burning desire to try it himself.[5] He asked the German for a piece of clay, but was refused. Artists’ clay was all imported at that time, and consequently was very precious and hard to obtain.

“It was with great difficulty,” said Mr. Kemeys, as he laughingly related the incident, “that I restrained myself from taking a piece of the clay. I tried down in the city to procure some, but could not. I wandered about the park for days thinking of nothing else but how I was going to get some of that clay. Finally a bright idea struck me. I would ask the old man to give me lessons. This I did, and went to his house the next evening. He sold me a little bit of the clay for $1. I never finished my first lesson. I got away as quickly as I could and went up-stairs to my room. I tried to light my candle, and I remember my hand shook so that my only match went out and I was obliged to run down-stairs for a few. I worked out the wolf’s head, and with the small bits of clay I had left I modeled my own little dog, “Lap.” When I had them finished everyone was in bed, and so I had to wait till morning to show them. I felt myself another human being. I sat by the window and waited for morning to come. I was certain of my success from the first. The old German would not believe that I had done the work myself, and when I took a piece of clay and modelled the wolf’s head before his eyes he immediately began to plan for us to go into partnership. But I felt myself expanding. I wanted no partners. And now when my fits of depression come on I know that I am going to get an image for a new figure or group. It comes to me always suddenly—like a flash. The idea gives me no rest until I work it out.

Moments of inspiration

“The picture for this group,” said the artist, turning toward a pair of deer, one recumbent and the other standing, “came to me as I was climbing over a fence out in the country. I was not thinking of modeling any deer at that time period I work almost day and night on the new subject until I am entirely exhausted. I work on a piece until I have it just as my mind conceived it. After all that I can do with hand and eye is done, I sit or brood over it until suddenly something comes to me and I go in a sub-conscious manner to the object, only touching, moving or changing it whatever seems but a mere jot. But until I have done this the work seems to lack the life spirit and is in fact mechanical.”

This creative power inspiration or genius marks the impassable line between men like Barye, Kemeys and the few and the host of aspirants for similar distinctions.

NOTES

[1] Kemeys’ lion sculptures were cast by Jules Berchem at the American Bronze Company, located at Seventy-Third Street and Woodlawn Avenue in the Grand Crossing neighborhood of Chicago.

[2] Florence Lathrop Field Page (1858–1921) donated the funds for the Art Institute’s commission to have the lion sculptures made by Mr. Kemeys. She was Mrs. Henry Field at that time, but Mrs. Thomas Nelson Page when the sculptures were unveiled on May 10, 1894.

[3] Although Chicago’s famous lions have no official names, Kemeys described the north lion as “on the prowl” while the south lion “stands in an attitude of defiance.” Clearly, he had these descriptions in place at the time that this article was written. The accompanying images show that he also had established their respective north and south placements.

[4] Kemeys prepared a staff copy of the Still Hunt for the 1893 World’s Fair. The sculpture adorned the north pedestal on the west end of the Manufactures Bridge, connecting the north side of the Electricity Building and center of the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building.

[5] This wolf’s head sculpture was such a formative experience that Kemeys signed many of his sculptures, including the Art Institute lions, with a wolf-head totem. The mark is clearly visible underneath his signature at the base of each lion statue.

Kemeys signed his name, wolf-head totem, and “1893” to each of the lions he prepared for the Art Institute of Chicago.

SOURCE

“Kemeys and his Work” Chicago Record Sep. 25, 1893, p. 5.

Leave A Comment