Every way

That you look in this city

There’s something exquisite

You’ll want to visit

Before the day’s through!

—“One Short Day” by Stephen Schwartz

The 2024 blockbuster film Wicked takes audiences into the thrilling dreamworld of Oz. While visiting the Emerald City, attentive viewers may catch glimpses of the 1893 World’s Fair.

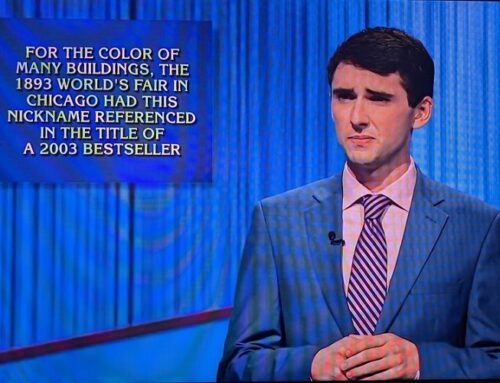

Ever since L. Frank Baum “discovered” the Land of Oz and published The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in 1900—seven years after visiting the World’s Columbian Exposition in his hometown of Chicago—his American fairyland has been reimagined countless times. One recent incarnation is the alternative-Oz invented by Gregory Maguire in his 1995 novel Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, reinvented as a spectacular stage musical in 2003, and now adapted by Universal Pictures and director Jon M. Chu into a two-part film. Wicked production designer Nathan Crowley has created a Land of Oz imbued with designs from the White City of 1893.

In a video on “How ‘Wicked’ Built Immersive Real-Life Sets, From Shiz to Emerald City” from Architectural Digest, Crowley discusses several inspirations for the architecture of Oz. He mentions [13:37] that because The Wizard of Oz is an American fairytale, he desired a “slice of Americana” in the film. Alas the video erroneously inserts several photographs of the 1905 White City amusement park in Chicago as he discusses the architecture of the Columbian Exposition fairgrounds. Crowley was intrigued by the relationship between the architectural illusion of the 1893 White City made of staff and the humbug Wizard in the Oz story … a connection that possibly, though not definitively, originating with author L. Frank Baum.

Especially eye-catching—to Crowley and to Fairgoers in 1893—was the Transportation Building. Louis Sullivan’s bold design was one of most controversial architectural features of the Columbian Exposition. The use of a polychromatic façade and the immense and elaborately decorated entrance arch, the famous “Golden Door,” made an extraordinary impression on visitors and critics. (Despite being called “golden,” the color scheme of the great arch was described by visitors as being “green and silver” or “silvered yellow.”)

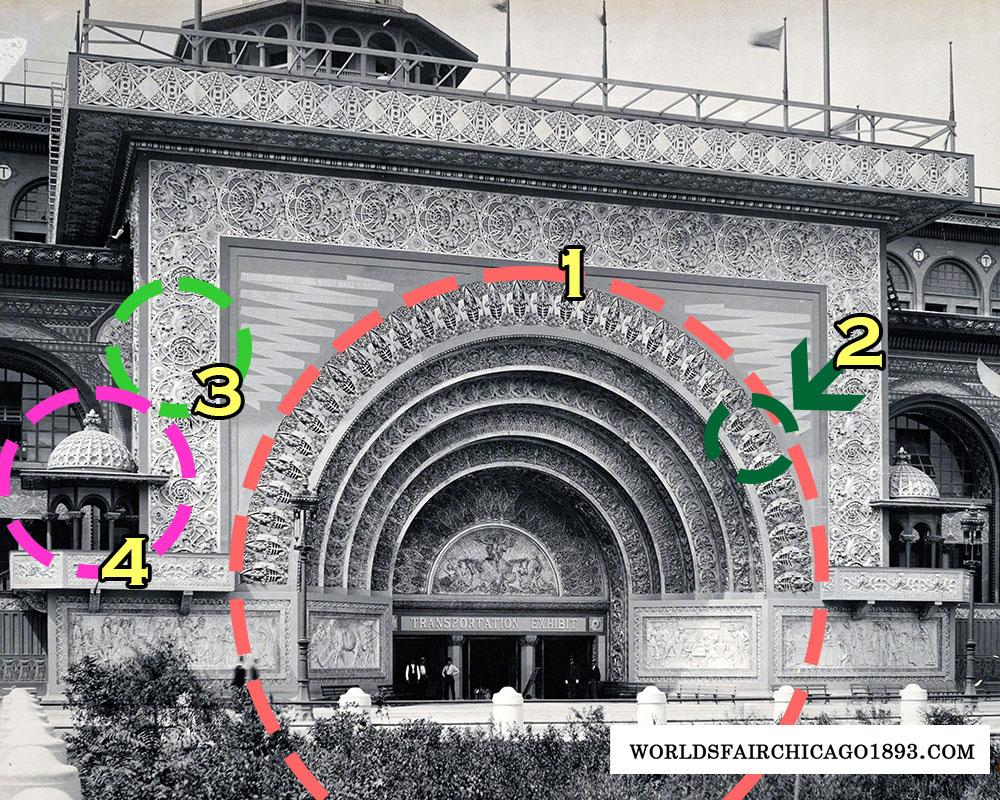

Four elements from Louis Sullivan’s “Golden Door” of the Transportation Building at the 1893 World’s Fair are used as decorative features in the Emerald City set for Wicked: (1) the iconic recessed arches of the entrance, (2) and (3) two types of high-relief decorative tile, and (4) the belvedere or kiosk at the side of the entrance.

In the Architectural Digest video, Crowley says he appropriated Sullivan’s “Golden Door” for the design of his Emerald City train station. This is a strange assertion, as the Wicked train station is a near-identical copy of the grand arch for the Chicago Stock Exchange Building, also designed by Adler & Sullivan in 1893. The shape of the arch and the large pendants in the spandrels are hard to miss. The decorative tile used in the arch of the Wicked train station, however, does borrow directly from the mandorla-shape tile used on the Transportation Building arches.

A Wicked set showing a train tunnel (under construction) bears a striking resemblance to Adler & Sullivan’s grand arch for the Chicago Stock Exchange Building (1893), saved and relocated to the grounds of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The decorative tile adorning the arch of the Emerald City train station is based on the arch tile used in the Golden Door of the 1893 Transportation Building.

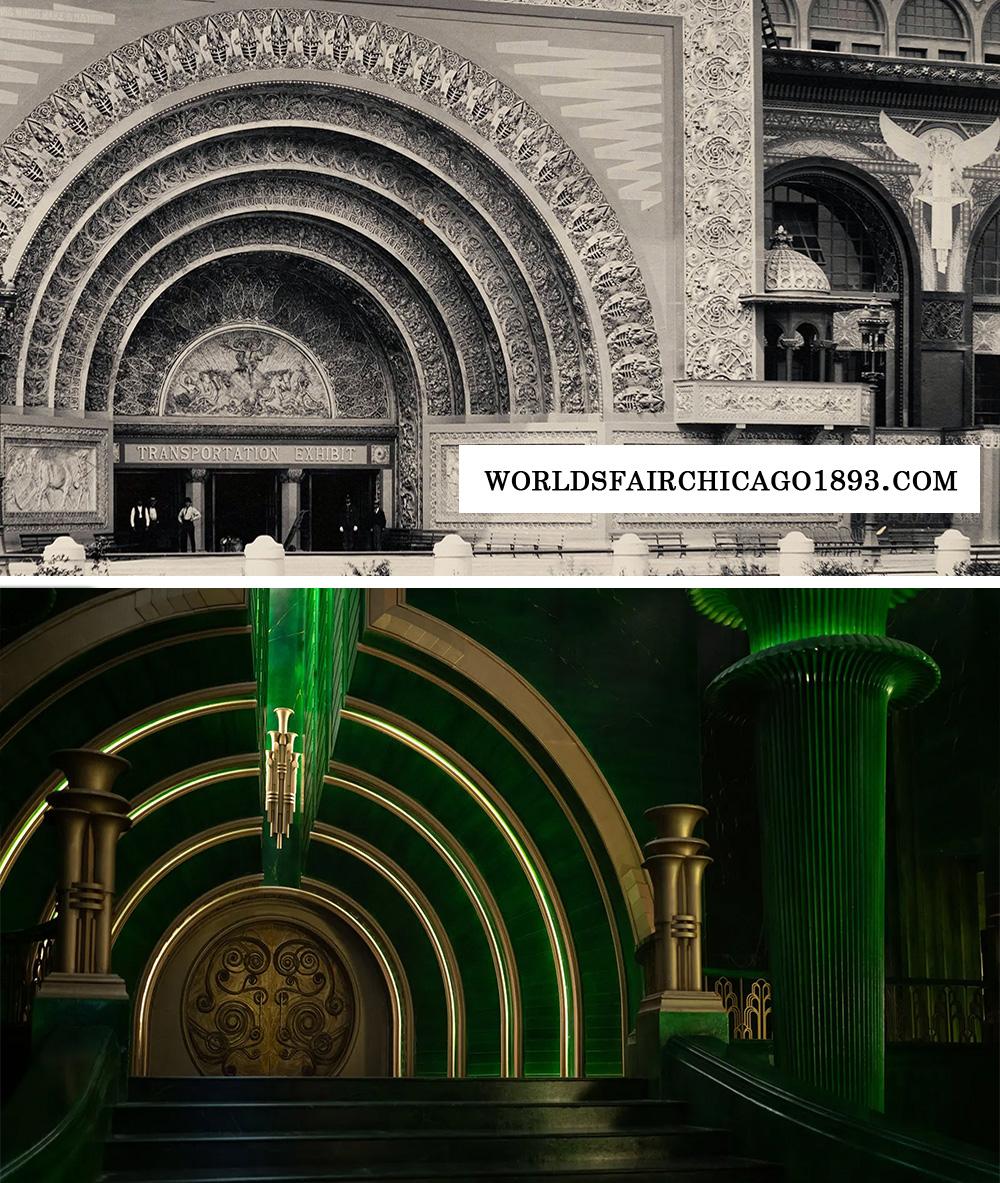

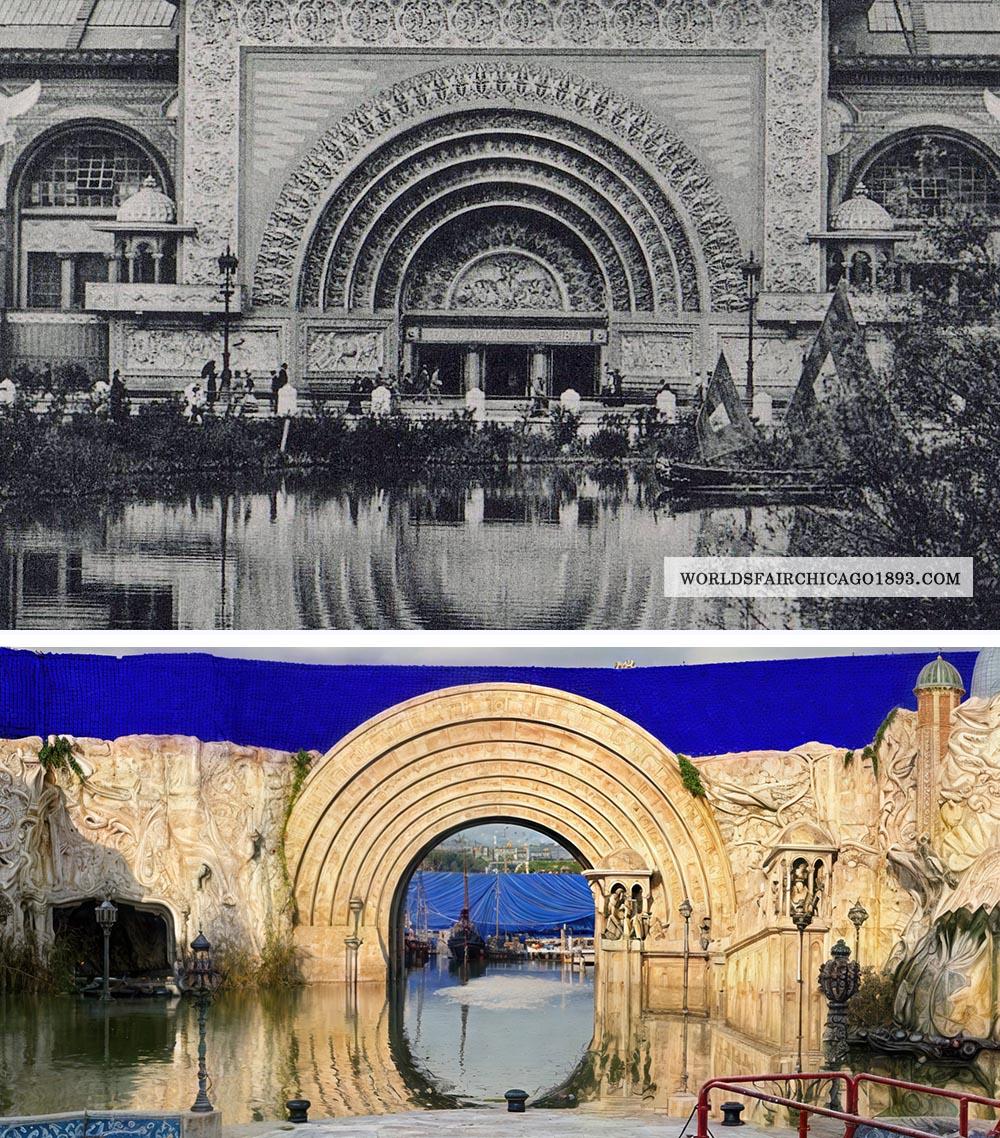

Elements of the 1893 Transportation Building, however, do show up elsewhere in Crowley’s set designs for Wicked. Sullivan’s Golden Door can be seen clearly in the entry arch of Wizard’s great hall in the Emerald City palace and in the entrance to Shiz University.

Sullivan’s “Golden Door” from 1893 provides inspiration for the arched portal into the Wizard’s great hall in the Emerald City palace.

The entrance to Shiz University, seen here during shooting, also borrows design elements from the “Golden Door” of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

Also making it to Oz are high-relief square decorative tiles and the belvederes or kiosks at the sides of the Golden Door from 1893.

High-relief square decorative tiles that framed the arched entrance to Sullivan’s 1893 Transportation Building show up in the Emerald City of Wicked.

The belvedere or kiosk the flanked the sides of the Golden Door at the 1893 World’s Fair can be spotted in the Emerald City.

In what may be just a coincidence, a theatrical production of The Wizard of Oz musical in 2019 also borrowed design elements from Sullivan’s 1893 Transportation Building for the look of the Emerald City stage set. [See our report “Louis Sullivan’s Transportation Building … in Green”] In these fascinating and creative ways, the architectural legacy of the 1893 World’s Fair and the American fairyland of Oz endure in Popular culture.

It all flashes by so fast, but this is a fascinating look at some of the design details.

Just saw the film Wicked. Should see it again after reading this article. I happen to be from Chicago and love it’s architecture!