The excerpt below, from The Chicago Record’s History of the World’s Fair, reminds us of the dangerous work that thousands of laborers (mostly immigrants) faced as they built the White City of 1893. The Medical Bureau of the Columbian Exposition officially reported only thirty-two deaths during construction of the fairgrounds. Luckily, the workers mentioned below escaped that fate.

[Note: Although the article mentions the first accident happening at the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, the location likely was the Agricultural Building, for which New York artist George W. Maynard executed all the decorative paintings in the pavilion and porticoes.]

Some curious instances of miraculous escape from death were known at the Exposition hospital. Perhaps the most curious as a coincidence happened to an assistant of artist G. W. Maynard and three workmen employed with him on the decorations of the manufacturers [sic] building. The four men were on the end of a horizontal platform twenty-five feet from the ground. The end of the platform jutted over the upright support several feet and the combined weight pulled out the spike fastenings that secured it to the upright. The four men fell. Each of the three laborers broke his leg at the ankle with almost exactly the same fractures, but the artist escaped with nothing worse than a serious jarring and a few scratches. He had come down on top of his companions, and their bodies probably saved him a month or two in bed.

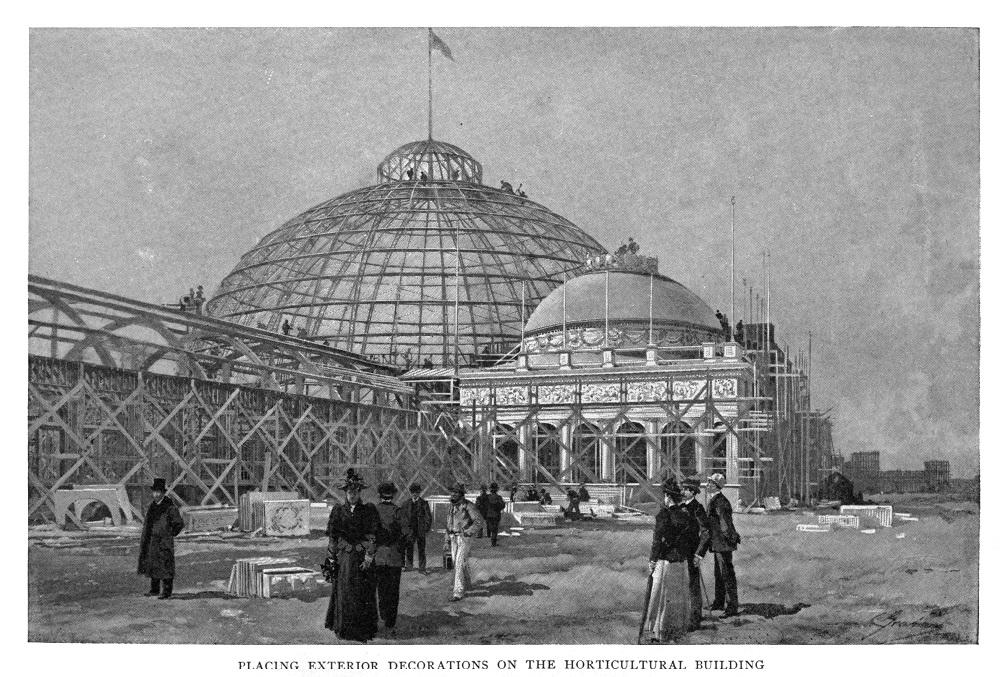

Charles Graham depicts construction workers “Placing Exterior Decorations on the Horticultural Building” during the winter of 1892. [Image from Harper’s Mar. 12, 1892.]

A guard who rushed up wanted to call a patrol wagon and take the man to the hospital.

“An’ why?” said surprised Patrick, “an’ why should I go? Will I lose my tolme and be docked? divil a bit will I. They’ll be dockin’ me now if I shtay longer,” and away he went, muttering imprecations on the stupidity of guards.

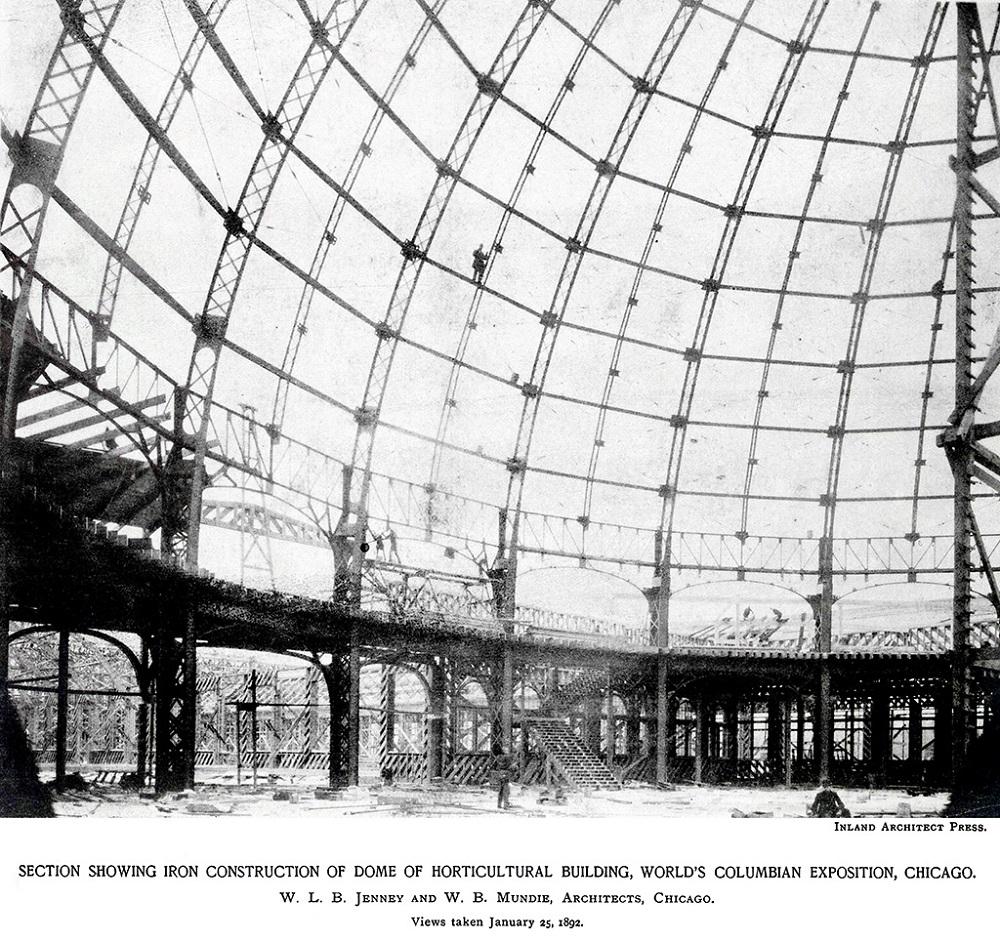

A photograph from January 25, 1892, shows workers climbing on the iron framework of the dome during construction of the Horticultural Building. [Image from the Inland Architect and News Record Feb. 1892.]

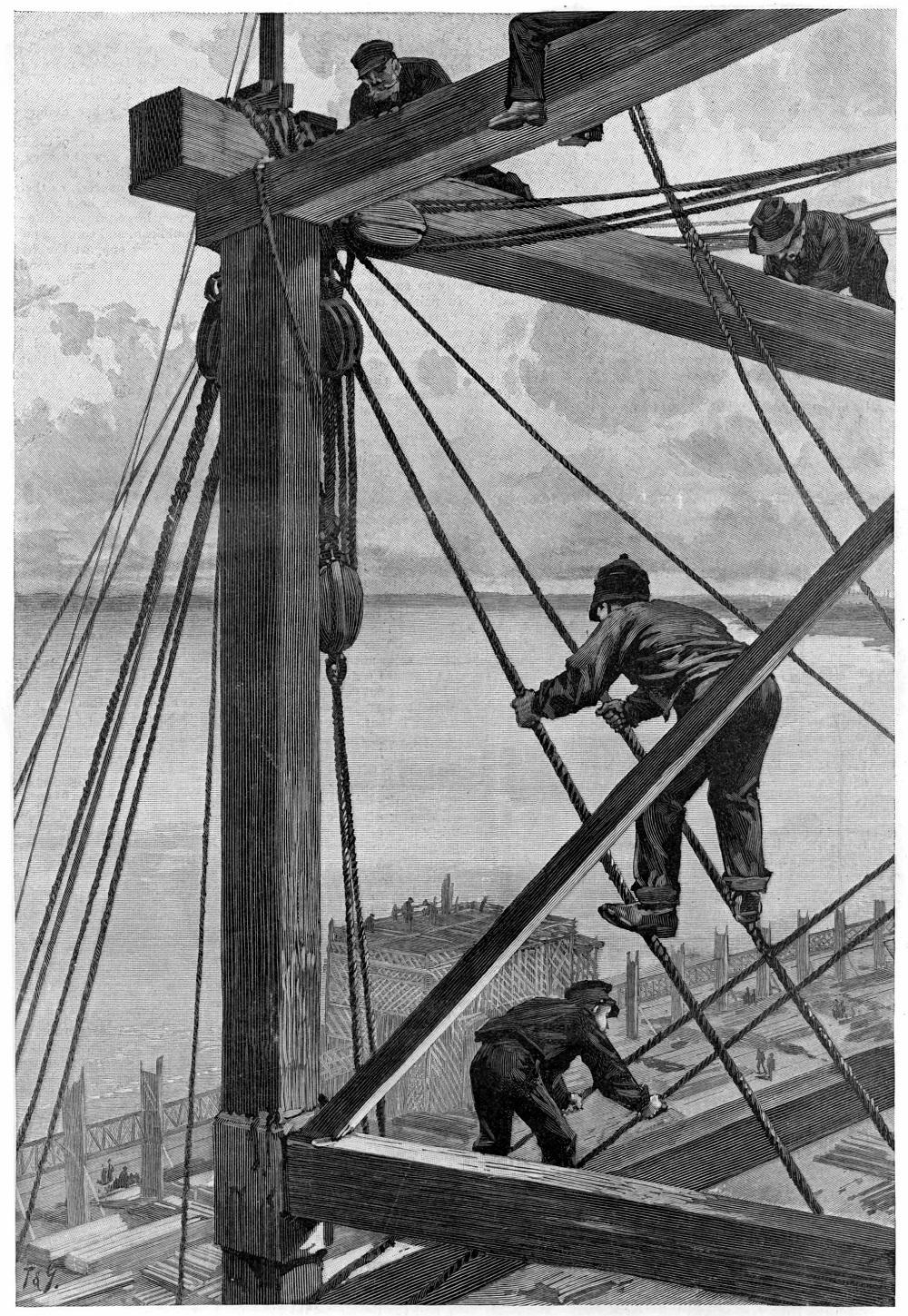

“The Great Derrick” used during construction of the enormous Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, as drawn by T. de Thulstrup and Charles Graham. [Image from Harper’s Weekly Mar. 26, 1892.]

An illustration showing artists climbing paint scaffolding inside the dome of the Administration Building as they paint William Dodge’s mural “The Glorification of the Arts and Sciences. [https://worldsfairchicago1893.com/2018/09/02/glorification-of-the-arts-i/]” [Image from Collier’s Once a Week Oct. 22, 1892.]

SOURCE

The Chicago Record’s History of the World’s Fair. Chicago Daily News Co., 1893. pp. 14–15.

Leave A Comment