In the aftermath of World War II—facing staggering military casualties, the atrocities of the Holocaust, and the specter of nuclear weapons—some people sought solace in fond memories of better times.

The following reminiscence of visiting the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago as a young boy appeared in the July 6, 1946, issue of the Windsor Star (Windsor, Ontario). The author had grown up in the small town of Morenci, Michigan.

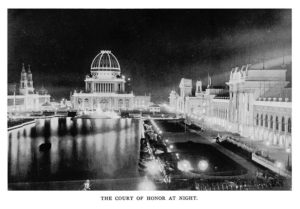

The “electric bulbs which outlined the dome of the Administration Building” left a lasting impression on a young visitor to the 1893 World’s Fair. [Image from Harper’s Weekly, June 24, 1893.]

Chicago Fair of 1893 Will Remain Unexcelled

By H. P. A.

I suppose now that the war in Europe is over, they’ll be getting up another world’s fair where the latest in radar and modernistic architecture will vie with some curvaceous female who will try to out-Rand our present day Sally of the fans and balloons as attractions. But I doubt if there will be half the kick in it was in the World’s Columbian exposition at Chicago in 1893. We have too many gadgets these days, and a new one is just one more. Even when you get them all together they are not as impressive as the electric bulbs which outlined the dome of the Administration Building at Chicago were to folks from a country town like Morenci where we got along with kerosene.

Nor would the next world’s fair be apt to get a better build-up than did the one at Chicago. That started, as I remember it, along about 1890, when I was getting along far enough with my reading so I could find out what the pictures in Harper’s Weekly and the Scientific American were all about and not be obliged to tease dad or mother to read the captions to me. Also, the Chicago fair had an extra year for publicity, as it was to have been ready in 1892 and they could not make the grade, so it was not opened until the spring of 1893, 401 years after Columbus discovered America, instead of 400, as had been intended. One of the best publicity stunts of that day was the sailing across the Atlantic from Spain of replicas of the three caravels which Columbus used in his voyage of discovery, and the visit to Chicago of the Infanta Eulalia of Spain. The Libbey Glass Company, I remember, made a glass dress for her, but it must have been very uncomfortable, as the glass cloth of those days was apt to exude splinters.

“One of the best publicity stunts of that day was the sailing across the Atlantic from Spain of replicas of the three caravels which Columbus used in his voyage of discovery.” [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

Dad’s Souvenirs

In our family, Dad was the first to visit the fair. He went to Chicago on the Wabash shortly after the fair was opened. I made life miserable for him and mother by teasing to go along, but they said no, as school wasn’t out yet and I had missed too much the winter before by having the measles. Dad brought home, among other things, a linotype slug with his name on it, and a single type character which he said he saw made on a machine that would make type and set it at the same time.

Dad said he thought the day would come when all the city papers would have their types set by machinery and it might even pay to get one for the Morenci Observer office, where he and Uncle Verne published the town’s weekly newspaper. There was also some “bum-bum” candy, the first sample I had ever seen of the spun sugar candy one gets in carnivals today. Dad admitted he bought it in the midway, where Little Egypt and her “hoochie-koochie” dance and the Ferris Wheel were the principal attractions, but he always denied having seen the show, which was making the papers regularly as the shocker of 1893.

Shortly after the Fourth of July, when things in Morenci were getting pretty dull for the boys and girls on vacation, mother announced that she was going to Chicago and that I could see the fair, but that I mustn’t make a nuisance of myself and ask too many questions, and all of that. I agreed to comply, knowing, as small boys always do, that promises were easy to make and that you could take your chance on the punishment meted out for non-fulfillment.

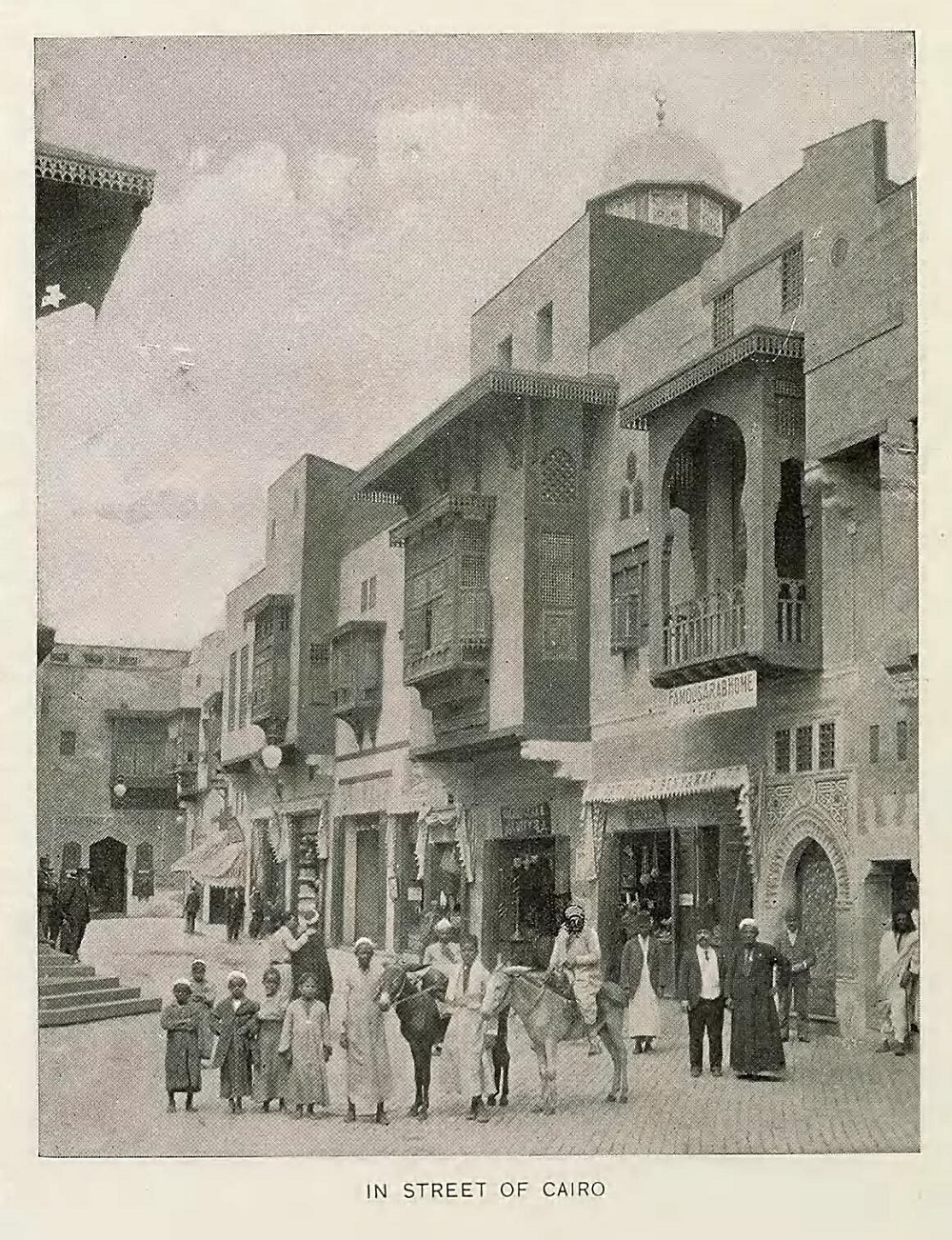

Visitors to the Midway could buy “bum-bum” candy in the Street in Cairo attraction. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

Electric Bugs

After a few days of boasting that I was going to see the world’s fair and making myself the envy of the boys and girls in our neighborhood, Mother finally accomplished the multitude of tasks entailed in getting ready for a train trip in those days, including two large shoe boxes of fried chicken, cake, Saratoga chips and other company foods for our lunch. We made the long trip to Chicago via the train on the Fayette branch of the Lake Shore and the main line, which was a grand outing in itself. As usual, Dr. Tallman, the husband of my mother’s cousin, Aunt Dell, was at the LaSalle street station. When we got to South Englewood the Tallmans were living in their grand new house and there was one of those wonders, an electric arc light, right in front of the place, where you could pick up, if you had the courage, one of those beetles known to my city cousin, Allen Tallman, as “electric bugs.”

But the glories of the train trip, the sights along the South Shore of Lake Michigan as our train approached Chicago, and even the “electric bug” soon faded the next day when the Tallmans and Mother and I made our first visit to the fair.

Many visitors to Chicago and the 1893 World’s Fair were in awe of the electrical lighting in the city and fairgrounds. [Image from Johnson, Rossiter A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Held in Chicago in 1893. (D. Appleton and Co., 1897).]

The Court of Honor

You may say what you like in favor of the modernistic architecture that broke out like an ugly rash at the last world’s fair in Chicago, the “Century of Progress” exhibition. It may be striking, and even convenient, but it was nowhere near as pretty as the famous Court of Honor in Jackson Park, Chicago, in 1893. And it was hard to realize that the beautiful, graceful buildings were just shams, made of plaster instead of solid stone. We stayed all day and lingered on at night, so we could see the electric fountain and the lavish illumination afforded by thousands of carbon bulbs on the buildings. And they, too, seem more beautiful than the miles of neon lights you see in cities today.

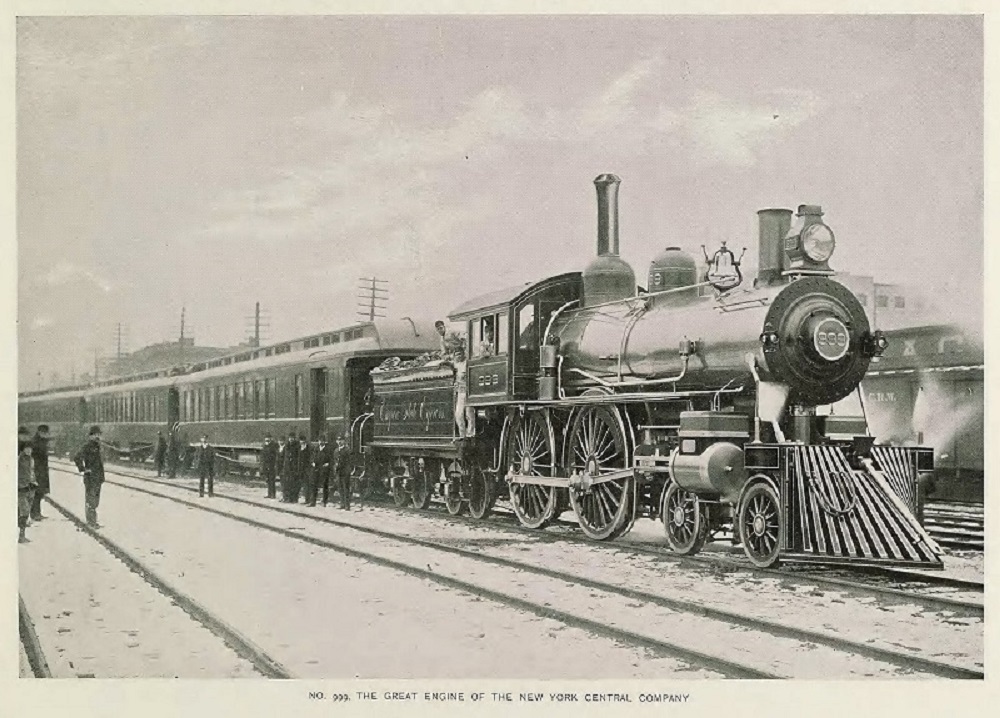

But for me it wasn’t the typesetting machines, nor the loom at which a real Turk wove Turkish towels by hand, or even the Jacquard power loom where you could see them weave fabric with pictures of the Administration Building on it, and even your name, if you wanted to pay the fee, that constituted the highlight of the fair. It was Engine 999, holder of the world speed record for steam locomotives.

At Morenci, where we boys had to be content with looking at “Old Dolly,” the locomotive which hauled the daily train on the Fayette branch, Engine 999 of the New York Central line was famous. We had games in which 999 figured. There was a Jingle which began “Engine, engine, nine ninety-nine, running on the Wabash line” (for the sake of meter I suppose), which we used to chant. Engine 999 was the fastest thing in the world then, and any one of us boys would have given almost anything we had just to have seen it.

The Empire State Express engine No. 999 on display in the Transportation Building. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

Awesome 999

Thus it was, when the Tallmans and Mother finally consented to go to the railway building, I was hardly interested in the replicas of the “DeWitt Clinton,” Stephenson’s “Rocket”[1] and other famous locomotives of early days, and spent what time they would allow me gazing in awe at 999.

Another highlight was a miniature train which ran ceaselessly around the balcony in one of the buildings,[2] and I had it figured out that the forward motion of the train turned a dynamo in it, to generate power for the electric motor which propelled it, and even argued a long time with Dr. Tallman, who knew better than that, but who could not convince me that perpetual motion of that sort was not feasible. For the reason of Mother being a bit timid, we did not ride on the Intramural elevated line, where electrically propelled trains took you anywhere in the fair grounds. But we did ride on a trolley line on one of the trips we made to get to Jackson Park from South Englewood.

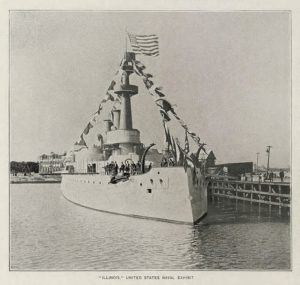

Also there was the Battleship Illinois which was at the end of a pier in Lake Michigan. It had very real looking cannon of the type which won the Spanish-American war for the United States Navy and there was armor plate and all of that and sailors and officers who looked very real. But Dr. Tallman said the ship was a fake, made out of bricks covered with iron plate. It would not sail at all, and that took some of the glory out of it.

The battleship U.S.S. Illinois exhibit on the lake shore. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

Nightmare Painting

Mother waxed very enthusiastic about the paintings in the art gallery, but I had a nightmare that night from looking too long at one huge canvas done by Gustave Dore. It showed the serpents which plagued the children of Israel in the Wilderness, all in accordance with the lessons you learned in Sunday School and was much too realistic.[3]

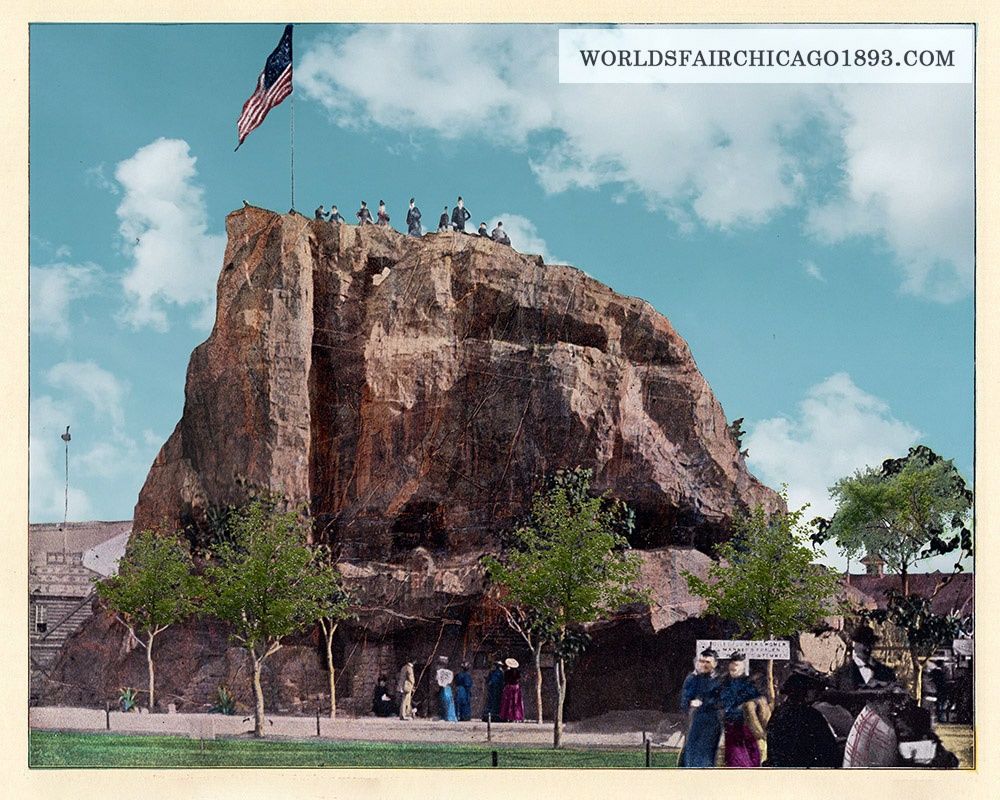

Mother had a nightmare too. Her’s, she said, came from a visit to one of the side shows, called the “Cliff Dwellers,” where you went up cliffs simulated in canvas, to see old pottery and shreds of cloth found in the deserted villages of the cliff-dwelling Indians of New Mexico and Arizona. Mother had quite a time of it and said afterwards she shouldn’t have gone into a place that even faintly resembled a cave.

Home again, the World’s Fair gave me much prestige until everybody in town and all the kids I knew got to going there on the low-priced excursions they ran on the Wabash. One could go to Chicago and back for as low as $2 when rail competition began to get hot. And there used to be a great lot of knowing winks among the men who had visited the “hoochie-koochie” show and seeing the bit of uncovered female pulchritude that would suffice to shock in those days.

However, dad continued to deny he had seen the show, and, of course, I was much too young to be accused. And everybody was singing “Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay,” which was one of the Midway songs. The Gay Nineties were off to a start.

The Cliff Dwellers attraction featured an artificial mountain with displays of Indian relics (and human remains), live animals, and cultural dance and music. [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894; digitally edited.]

NOTES

[1] The author may have mistaken this for Robert Stephenson’s “John Bull” train, which was a popular train exhibited in the Transportation Building.

[2] This model train exhibit was in the Kansas State Building. One visitor complained of the toy train “torturing ear and forbidding our enjoyment.”

[3] The Official Catalogue for the Fine Arts Department does not list any paintings by Gustave Dore being exhibited in the Palace of Fine Arts. The famed Dore Vase (Le Poème de la Vigne) was exhibited in the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building.

SOURCE

“Chicago Fair of 1893 Will Remain Unexcelled” Windsor Star (Windsor, Ontario), Jul. 6, 1946, p. 29.

Leave A Comment