The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition showcased harmony of architectural design and sculpture, advanced technologies to serve humanity, and education to guide moral progress. These themes are featured in the essay reprinted here, from the July 1893 issue of Catholic World.

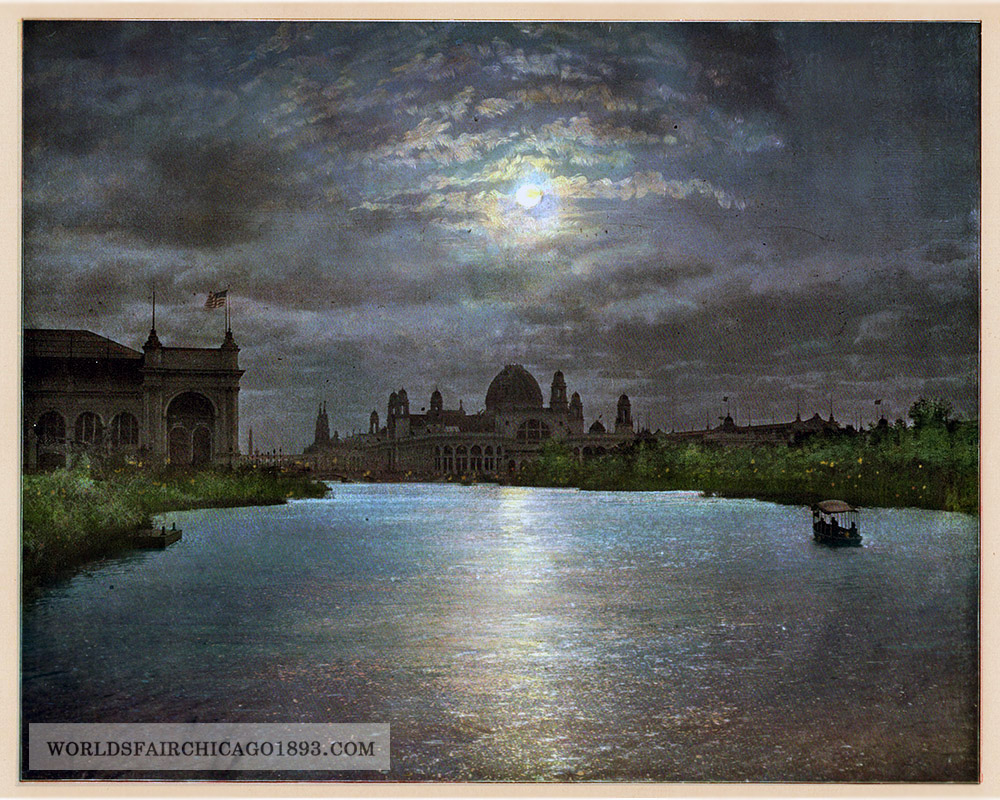

This depiction of the “East Lagoon by Moonlight” typified the dreamy quality of “the great white ephemeral city.” [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894; digitally edited.]

A CITY OF REALIZED DREAMS

Wandering through the spacious grounds and amidst the magnificent halls of the great white ephemeral city—and what a pity it should be ephemeral!—by the shores of Lake Michigan, a multitude of thoughts must crowd upon the mind of the visitor. The external impressions alone must form an ineffaceable memory. Rarely has such a splendid coup d’oeil been unfolded as that which greets his vision as it strives to take in the varied panorama. In architectural arrangement, in amplitude of extent, in harmony of design, the congeries of snow-white structures which have sprung up on the site of what has been a comparatively barren and solitary public resort eclipses every other system of buildings ever grouped together under the name of a “Universal Exposition.”

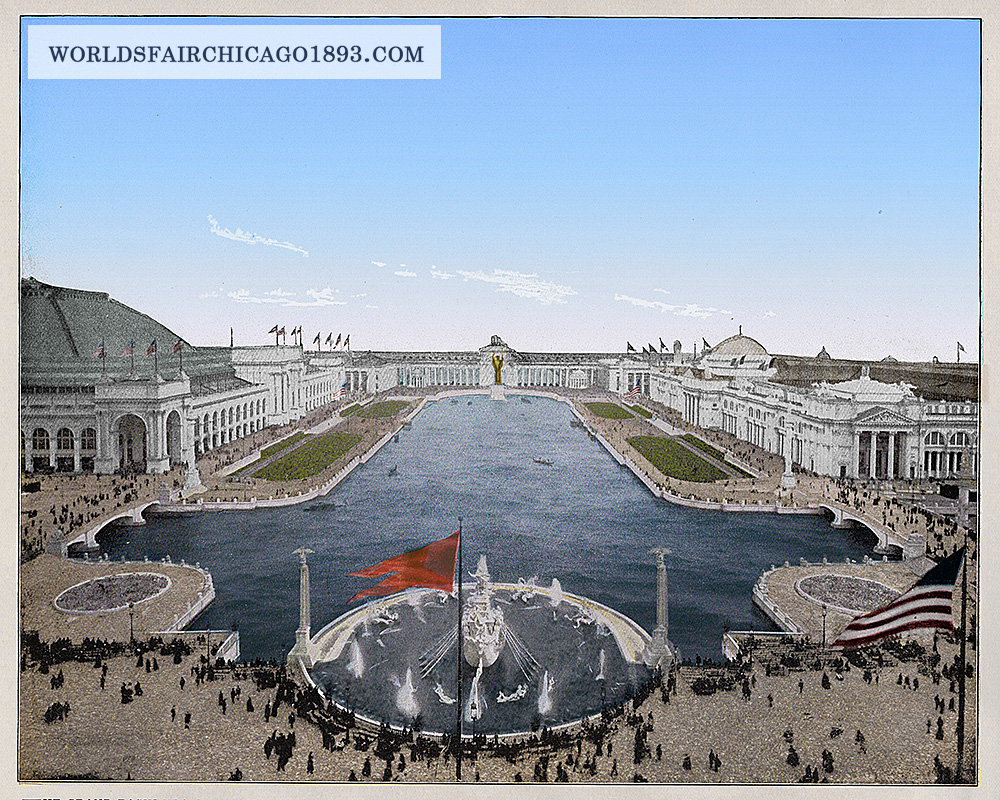

The White City displayed “perfect unity in the composition of a great whole.” [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894; digitally edited.]

Such perfect unity

Now, this is no hyperbole. The observer who has had an opportunity of noting the architectural excellences of the various other World’s Fairs, in Europe as well as upon this continent, will admit that, beautiful in conception and arrangement as many of these were, in none did harmony in detail work out to such perfect unity in the composition of a great whole as in this gigantic memorial. The great extent of ground to be covered to some minds might have seemed to demand variety not only in form but in color of the buildings destined to adorn it. But the adoption of a uniform plan has secured an effect which no other could possibly have produced. There is a homogeneity in the classic lines of those great edifices, differing as they all do in architectural style, which derives its completeness from the adoption of white for their outer covering. They seem like substantial palaces of snowy marble, and at certain points of view the vistas presented are superb. The adoption of the more usual plan of glass and iron as materials never achieved any such result as this. So then we have to mark a great distinctive advance in the stateliest of human arts—that of architecture. If we have as yet been unable to found a school, the Columbian Exposition proves that we have learned one great essential—that is, assimilation; for the thorough fitness and adaptability of the great structures erected by Lake Michigan to the surroundings of the place and the uses for which they are intended at once impress themselves upon the beholder with all the conviction of a self-evident fact.

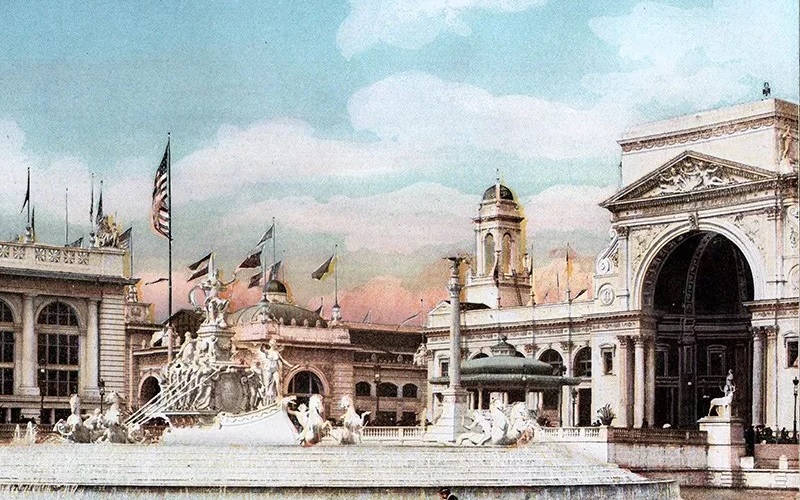

The “great fountain at the side of the lagoon opposite the peristyle” was designed by Frederick MacMonnies. [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894; digitally edited.]

Our sculpture reflects the spirit of our age

The crowning glory of all architecture is the sculpture which is necessary for its illustration and embellishment. Most of the sculpture incidental to the Fair buildings, considering its temporary character, is admirable—at least in conception. In the groups especially is this the case. In general effect, in harmony of design, and in the observance of the golden mean between the heroic and the real in human proportion, the palm must be given, many will own, to the noble trophy which forms the great fountain at the side of the lagoon opposite the peristyle. It is a piece symbolizing the triumph of Columbia. America, represented by a female figure, sits enthroned in a gorgeous classic barge, with Fame guiding, and four other female figures rowing. Youths with sea-horses swim in front, and mermaids disport upon the water. In such a composition there must, seemingly of necessity, be to one who discards mediaeval or more ancient examples, a great temptation to lapse into what is known as rococo; but the sculptor has avoided this pitfall. There is no exaggeration in his treatment; the abandon of these water-myths appears perfectly genuine and natural. The largeness of touch that one remembers in some of the great ornamental fountains at Versailles, the Rubens-like rotundity of those watersprites, and the majestic if somewhat theatrical anatomy and pose of the Neptunes and Amphitrites in these fine old masterpieces have beauties of their own; if there is a more modern spirit in our latter-day compositions, there is at least a unity about them and a fidelity to the modern idea of exactitude in detail which stamp them with a distinctive character.

We have discarded the heroic, to a great extent; we are permeated with the sense of the appropriate and the practical; and this is, one may say, speaking broadly, the prevailing characteristic of the sculpture at the World’s Fair. This is not to be wondered at. Our sculpture reflects the spirit of our age, as well in its physical development as in its ideas of illustration. This was the chrysalis state of the art, doubtless, in every nation which struggled for the attainment of a higher ideal. We are a young people, as the world goes; and we prefer originality, even though it be sometimes crude, to mere servile aping of others’ ideas, however exalted. Our practical views incline us to realism; later on we shall have mastered the secret of making the real serve as the foundation of the poetic.

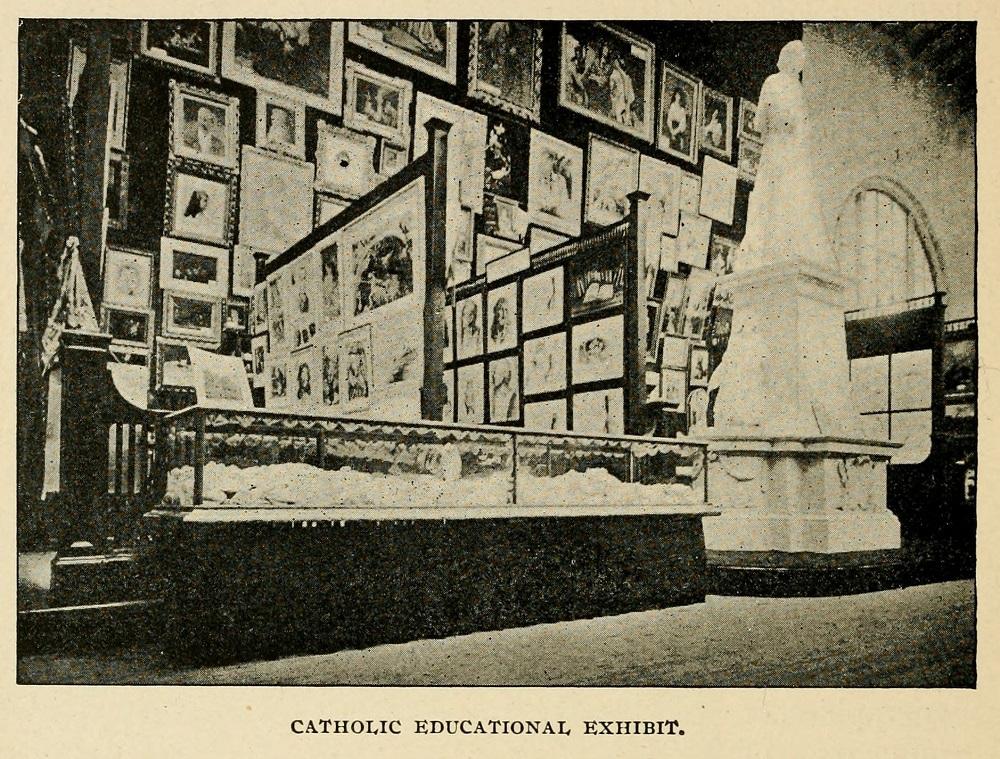

The Catholic Educational Exhibit in the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. [Image from White, Trumbull; Igleheart, William World’s Columbian Exposition Chicago, 1893. J. W. Ziegler, 1893.]

A feeling of calm assurance for the future

How are we laying out for the future? This is a more absorbing question than what we have done for the present. We occupy a unique position before the world. The territory given this free people to mould and round into the finish of superlative greatness is the vastest of any on earth; in language, polity, commercial system, national aims, it is one from ocean to ocean. It is untrammelled by monarchical traditions and ambitions, free from dynastic combinations, unperturbed by those war-clouds which in the older world are perpetual. Its way lies clear before it. It is to be known to all the future ages as the Great Republic; and the uses to which it shall put its unshackled liberty depend largely upon what we of the present day are doing for those who are to succeed us. Hence the interest which attaches to the educational section of the Exposition is highest of all.

It is deeply gratifying to note that far and away the finest display of the effects of technical training is that made by the Catholic schools throughout the States. The exhibit covers an area greater than that of nearly all the other denominations put together, and it bears eloquent witness to the indefatigable zeal of Brother Maurelian and the other members of the teaching community who devoted themselves to the task of putting it in evidence. Imperfect as was its condition when our cursory examination was made, it was impossible not to be struck by the excellence of the work done in the Catholic schools by juvenile students, not only in the mechanical but in the higher arts. Grown men who had spent their apprenticeships to trades could not turn out better work in some of the classes; the drawing, modelling, and painting would do credit to much higher schools in many instances. To know that while the thousands of little men whose handiwork is here visible are being sedulously prepared for the moral duties of life, their faculties are being developed so as to best fit them for its practical side, gives a feeling of calm assurance for the future.

This is a practical age, and the battle of life must be fought upon that line. Of this fact our Catholic teachers are fully aware, and they adapt their system of training to meet the conditions. Of the part played by the order to which men like Brother Maurelian, Brother Azarias, and Brother Quintinian belong, in the training of the successful Catholic business men of our day, all over the world, not many outside their own ranks know, for the historian has not yet risen. But it is great, and, as this Catholic Exhibit shows, increasing in its greatness as the world goes along.

A view looking down Columbia Avenue inside the mammoth Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, where exhibits offered a “technical education” to visitors. [Image from The Graphic History of the Fair. Graphic Co., 1894.]

The realization of the dream of a thinker

The forte of this American nation seems to be, so far as can be discerned, in the arts of peace. Its ambition does not seek an outlet in the construction of mammoth artillery like that of Germany. The steam-engine, the electric motor, the agricultural machine, lie more in her métier. In every art and appliance calculated to make the wheels of life and industry run smoother, she stands a claimant to excellence. In many the youngest of nations has outstripped the oldest in experience and reputation. A careful study of the exhibits in the Manufacturers Building is a cycle of technical education.

Of the ten thousand things which challenge attention in this marvellous Exposition it would take a tome to tell. There is hardly a branch of science or industry here represented by its instruments or its machinery which is not the realization of the dream of a thinker. Each is an education in itself in its special field, and each has its own peculiar history. They tell us in their mutely-eloquent way of the wonderful growth of the world in knowledge in the past half-century, and they set us thinking on the possibilities of the future. These are of the material world, however, and “man does not live by bread alone.” There is the great moral world to be considered, without whose controlling influence material success must be a barren triumph.

The congresses have well begun. From two of those which have been held, in especial, momentous results may be expected. We refer to the Congress of Catholic Women and the Temperance Congress. It will be our privilege to lay before our readers in the next issue special articles on these important gatherings, with portraits and other illustrations relevant to them. From the other congresses which are to be held at a later portion of the year results likely to have a lasting influence upon the moral progress of the nation, if not upon the outside world as well, may reasonably be looked for.

A word as to the probable success or failure of the Exposition for the vast multitude who have invested their money in it may not be altogether out of place. An outlay altogether unprecedented in the history of these international undertakings has been made, and up to the present the attendance has not nearly approached that which would be necessary to enable the investors to look forward to a return of their money. The cause of this failure is, in our opinion, the unsympathetic action of the great railway companies. These have drawn a prohibitive cordon around the Exposition, and so prevented the masses of the people from going to Chicago. If they cannot be made in time to see the unwisdom as well as the unpatriotism of their attitude, the World’s Fair is doomed to be a gigantic loss to those who have subscribed for its erection. Some plain speech from the New York press is called for, we think, upon this matter—and speedily.

SOURCE

“A City of Realized Dreams” Catholic World July 1893, pp. 566–69.

Leave A Comment