Fair of the Future—Chicago’s International Exposition, A.D. 2000:

Introduction

“If you don’t think about the future, you cannot have one.”

—English novelist John Galsworthy

To celebrate the upcoming opening of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, the American Press Association solicited prognostication by notable people as they looked one hundred years into the future. The series, which ran in newspapers in early 1893, included essays by distinguished thinkers of the day such as populist politician William Jennings Bryan, industrialist George Westinghouse, orator and politician Chauncey Depew, author and publisher Kate Field, humorist Bill Nye, and 69 other commentors. David Walter compiled the essays in Today Then: America’s Best Minds Look 100 Years into the Future on the Occasion of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (Farcountry Press, 1992).

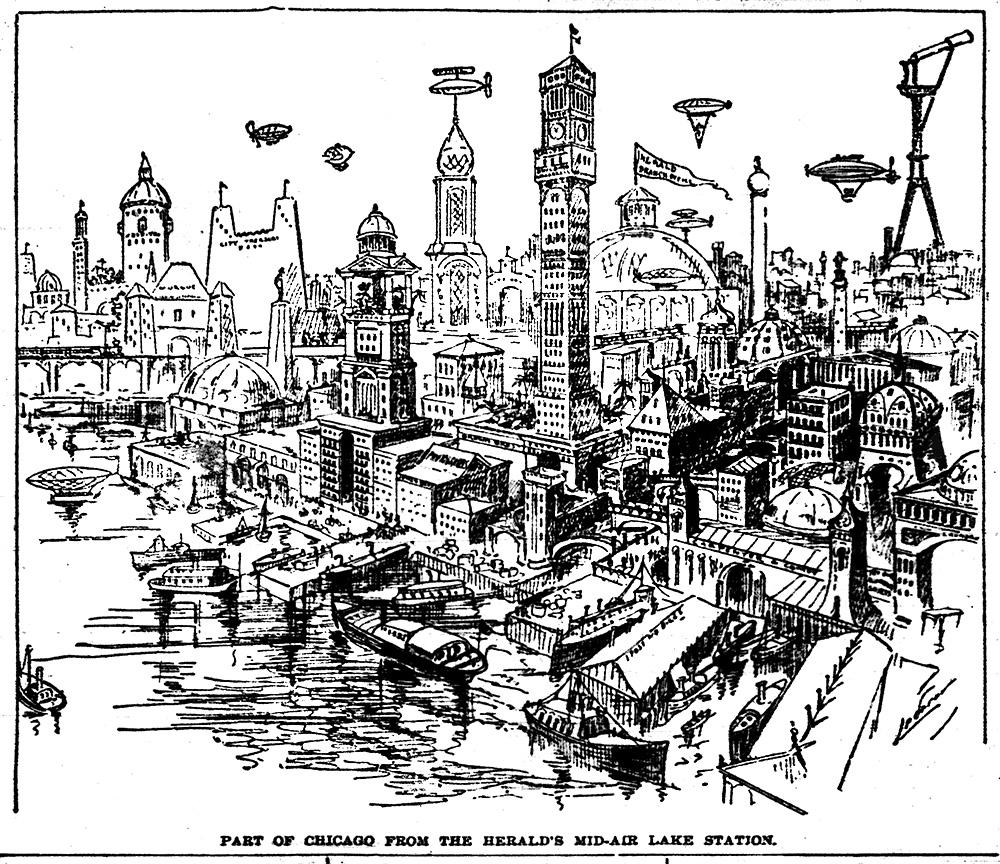

Looking forward was a popular activity around the time of the World’s Columbian Exposition, with scores of futurist and utopian novels published in the 1890s. Among most popular and influential writings of the Gilded Age was Edward Bellamy’s novel Looking Backward: 2000–1887 (Ticknor & Co., 1888). At the time of the Columbian Exposition, Bellamy published a short essay comparing the 1893 World’s Fair to his imagined World’s Fair of A.D. 2000 (see “Edward Bellamy Looks Backward to the 1893 World’s Fair“). On Opening Day of the 1893 World’s Fair, the Chicago Herald published an eight-page “supplement” from one-hundred years in the future. Their “May 1, 1993” edition was chock full of imaginative technologies, politics, and social issues of the future.

This vision from 1893 of the future Chicago in 1993 includes colossal skyscrapers, airships, and a giant telescope. [Image from the Chicago Herald May 1, 1893.]

An imaginary International Exposition

The Chicago Times-Herald got into the game a few years later. The paper ran a regular contest for original stories submitted by readers, and advertised in their January 26, 1896, issue that “Prize Offer No. 12” would be awarded for “the best description of an imaginary International Exposition held at Chicago in the year A.D. 2000.”

Submitted stories were not to exceed 1,000 words and would be evaluated on (in order of priority) “literary excellence of the contribution, its originality, freshness of style, punctuation, penmanship and neatness of manuscript.” The prize editors also advised writers to “avoid the use of slang.” The paper offered cash awards for the first prize ($20), second prize ($10) and third prize ($5) submissions, and all published entries were also paid three cents per line or six dollars per column. (For reasons unknown, the prize amounts differed for various offers—higher for the contest on “Stories of Adventure” and lower for “How I Smoked My First Cigar,” for example.) Submissions came in from all over the country.

The Chicago Times-Herald Prize Stories for “Prize Offer No. 12” were published in the February 2, 1896, issue.

Winning submissions

The Times-Herald published the winning entries in its February 2, 1896, issue. First Prize went to Percival Owen of Nebraska City, Nebraska, for his story “Chicago’s World’s Fair, A.D. 2000.” Owen had published a story in an Omaha newspaper in 1892, but otherwise he does not appear to have developed into a professional writer. Winning Second Prize was Mary F. Arnold of Terre Haute, Indiana, for her story “Greatest of All.” Based solely on the stated judging criteria—and without the hindsight of knowing its now-famous author—it is very hard to imagine how either of these entries beat the final story.

L. Frank Baum in the White/Emerald City. [Art by Mawhyah Milton for PBS.org.]

An American fairyland

Earning the third-place prize was “Yesterday at the Exposition [From the Times-Herald, June 27, 2000]” by L. Frank Baum of Chicago. Although few people at the time would know the name of this traveling salesmen, Baum soon burst onto the literary scene to become one of America’s most famous authors. After his moderately successful Mother Goose in Prose (1897) came the best-selling Father Goose: His Book (1899) followed by his magnum opus about an American fairyland, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900).

His 1896 short story for the Times-Herald is among his earliest fiction writings that were professionally published. The same paper recently had printed two other stories by Baum (“They Played a New Hamlet” on April 28, 1895, and “Who Called ‘Perry’?” on January 19, 1896) as well as two of his poems (“La Reine est Mort—Vive La Reine” on June 23, 1895, and “Farmer Benson on the Motocycle” on August 4, 1895). Before moving to Chicago from South Dakota in 1891, Baum had dabbled with futurism in some of his satirical “Our Landlady” columns that he wrote for his own newspaper, the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer.

While living on Chicago’s West Side, L. Frank Baum and his family visited the 1893 World’s Fair several times, though he seems not to have recorded his experiences at the Exposition. It is not known if either Percival Owen or Mary Arnold made the trip to Chicago and used personal memories of visiting the White City to guide their story creations.

On the basis of the texts, Baum’s submission to the Times-Herald soars above those of Owen and Arnold. By taking a look at examples of Baum’s left-leaning handwriting, we might wonder if his submission was dinged in the category of “penmanship and neatness of manuscript.”

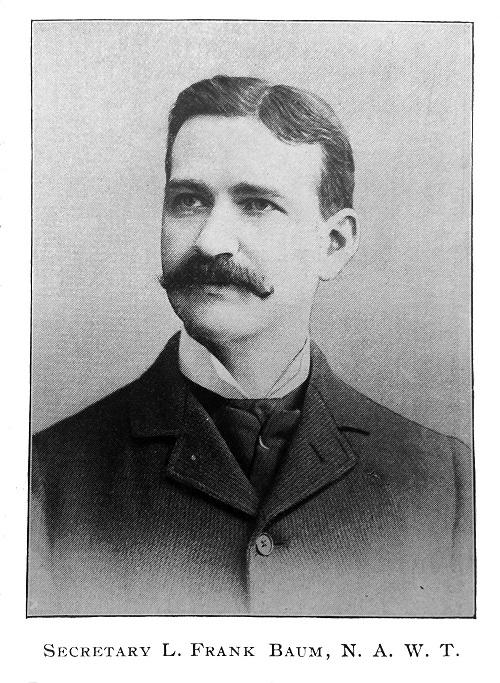

Portrait of L. Frank Baum in 1899, when he served as the Secretary of the National Association of Window Trimmers of America. [Image from Baum’s publication The Show Window September 1899.]

Fantastic fair futurism

In their short pieces, all three authors touched upon some subjects that often appear in futurist writings. Although they describe fantastic inventions such as food pills and “solid air” used as a building material, the underlying science is quite shaky, even for 1896! Two of the stories mention feats of geoengineering on a mythological scale. Percival Owen opens his story with the absurd idea of standing Lake Michigan “on end” (whatever that means), and Mary Arnold describes man-made mountains in Chicago.

Better predictions are offered about future forms of transportation. Mary Arnold and L. Frank Baum each seem to anticipate the development of automobiles; she mentions electric-powered wheeled chairs, while he describes “motorcycles” and pneumatic cars. They both also envision airplanes; she writes about aerial cars, and he about air ships). Owen’s remark on “instantaneous newspapers” is the only example of a future communication technology.

Although a larger City of Chicago is implied, none of the authors specifically address population growth and its consequences, an anxiety addressed by many futurist writers in the twentieth century. Ecological threats also are barely noted, though—in an interesting coincidence—two of the authors predict the extinction (or near-extinction) of horses for some reason.

New York gets a good ribbing in two of the pieces. Owen imagines New York City becoming a foreign country that fails to progress beyond the late nineteenth century, while Baum describes the “consolidated conceit” of New Yorkers and their fate in the year 2000. The rivalry between Chicago and New York continued to simmer in 1896.

All three authors list their predictions for changes in the nations of the world, their governance and global power. Owen and Arnold both allude to the end of the British royalty. England is out and New Minnesota is in. American imperialism will add some new stars on the U.S. flag, we are told. Will France and Germany diminish to a “staid old couple” and Russia become a colony of Japan? Will Ireland fracture into hundreds of kingdoms or be united under a President? Read on to find out.

Continue reading:

First Prize: “Chicago’s World’s Fair, A.D. 2000” by Percival Owen

Second Prize: “Greatest of All” by Mary F. Arnold

Third Prize: “Yesterday at the Exposition [From the Times-Herald, June 27, 2000]” by L. Frank Baum COMING SOON

Leave A Comment