A prolific writer of prose and verse, Nixon Waterman (1859–1944) is credited with having conducted the first all-verse column in newspaper history, for the Chicago Herald. He lived and wrote in Chicago in the years before and during the 1893 World’s Fair. Waterman’s light-hearted and pun-riddled verse, often on topics of Christopher Columbus or the emerging Exposition fairgrounds in Jackson Park, filled spots throughout the run Jewell N. Halligan’s Illustrated World’s Fair, published from 1891 through 1893. “Without his clever short rhymes our pages would have been dull and commonplace,” wrote his editor.

Reprinted below is Waterman’s fanciful look at the Columbian Exposition through imaginary spectacles. His fantastic tour of the fairgrounds, “I Had a Dream That Was Not All a Dream,” ran in the October 1892 issue of the Illustrated World’s Fair.

Nixon Waterman. [Image from the Illustrated World’s Fair Oct. 1892.]

“I HAD A DREAM THAT WAS NOT ALL A DREAM.”

It is is my good fortune to reside close to Jackson Park, where is to be held the Columbian Exposition. A few days ago I started at an early hour on one of my occasional sight-seeing tours through the grounds. I had gone over the same paths a score of times, yet my frequent visits had, seemingly, in no degree lessened my appreciation of the wonderful size and marvelous beauty of the many buildings there to be seen, nor rendered commonplace the view presented.

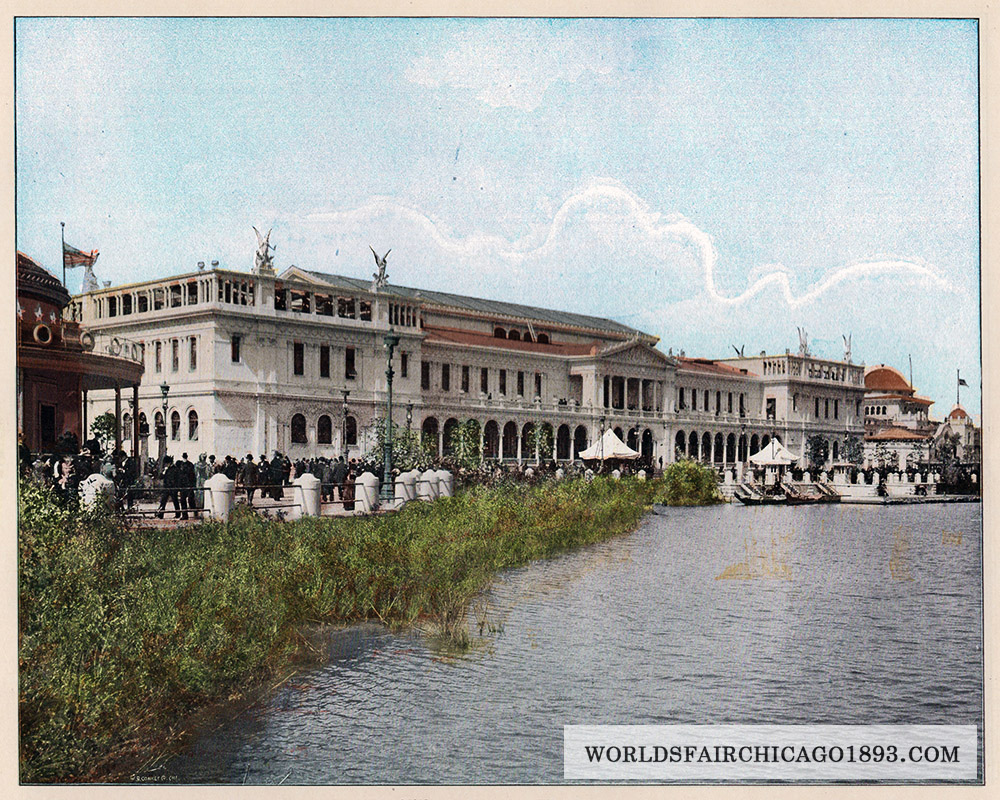

The Woman’s Building, designed by Sophia Hayden. [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894; digitally edited.]

To the south, as I wandered on, I saw the Horticultural building, that measures its length of glass and glitter by a thousand feet, and wherein the limitations of zones and isothermal lines are put aside, and where the feeble spark of plant life that exists in Icelandic moss may gaze with open-eyed wonder at the mighty palms of the tropics, and both may enjoy the beauty of shrubs and plants and flowers collected from the far and near corners of the earth.

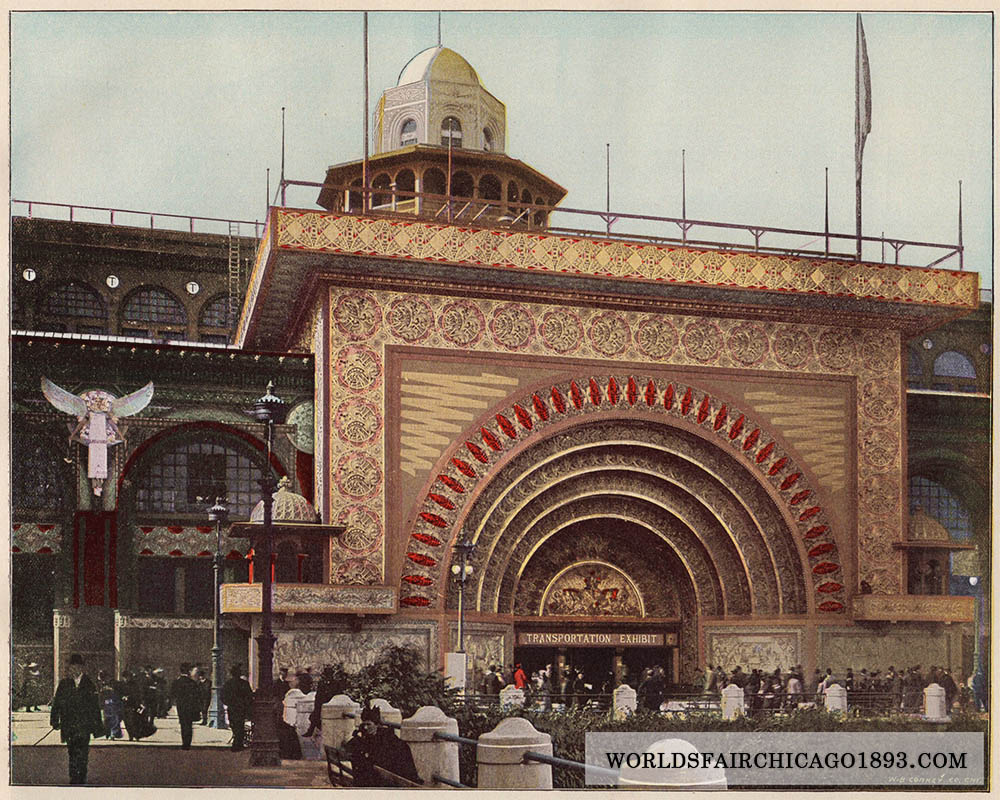

The “Golden Door” of the Transportation Building, designed by Louis Sullivan. [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894; digitally edited.]

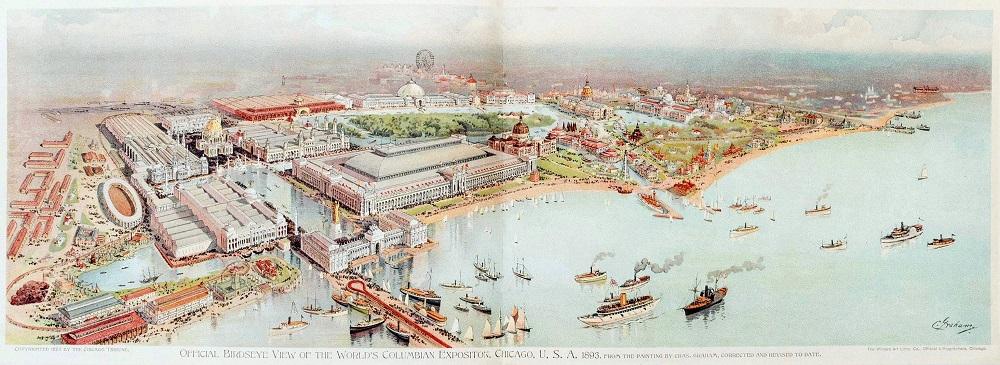

A bird’s-eye view of the 1893 World’s Fair by Charles Graham for the Chicago Tribune.

Hours slipped rapidly by in contemplating the structures designed to commemorate the flight of centuries. It was, as I remember it, nearing noon when, after having enjoyed a rest while sitting in a quiet, shady nook, I was again turning my steps from the scenes of glittering grandeur, that my eye beheld a great tower I had, strangely enough, never before seen. The structure was supplied with an elevator service, and, upon invitation so to do, I ascended to the top of the tower, where a courteous attendant informed me I was 2,000 feet above the earth. The view that spread around was one never to be forgotten. The mighty architectural triumphs all about me, each great building grand and ample enough to be the home of a demigod; the crystal lagoons surrounded by grassy lawns and resembling great diamonds in settings of green; and beyond, on the one hand the walls and domes and spires and chimneys of a mighty city, and on the other, Lake Michigan, beautiful in the lights and shades of sun and cloud.

“Wonderful!” I said, half to myself and half to the attendant, who responded with, “Yes, the preparations being made for our World’s Fair surpass anything men have ever seen. But what your eye beholds being done here in this great stretch of park is only a small part of what the world is doing. Here, look through these,” said he, handing me what appeared to be a pair of ordinary gold-rimmed spectacles. “Place them close up to your eyes to begin with,” he added, “and then as you wish your view extended slide them further down your nose.”

I did as he directed. The spectacles possessed a peculiar power. They did not seem to magnify, but rather to make objects hidden by distance from the naked eye to appear as though near at hand. I looked first at the great city whose pushing, enterprising people secured the holding of the World’s Fair, and whose persistency and integrity insures its unqualified success. I saw great blocks of buildings rising on every hand, additional height being added to those already standing and an air of vigorous improvement apparent everywhere. The city impressed me as being one vast hive of humanity busily preparing for the corning guests.

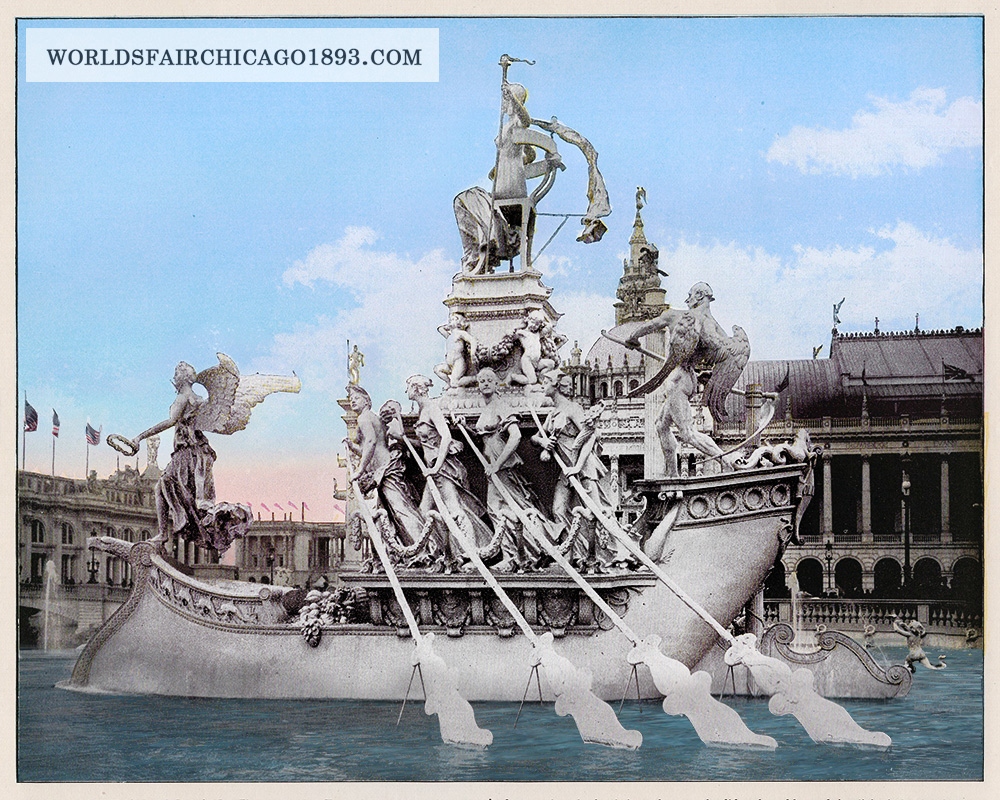

Among the most admired sculptures at the Columbian Exposition was Frederick MacMonnies‘ Columbian Fountain. [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894; digitally edited.]

And I looked across the prairie states of the Mississippi Valley and I saw the farmers selecting the choicest sheaves of grain and caring for the fields of stalwart corn whose golden products shall be nature’s princely garniture for the World’s Fair. I saw the great wheat fields of the Northwest, and the swarthy harvesters as they met in their rounds of labor chatted about the great World’s Fair, as did also the men with axes and picks in the forests and the mines of the North and East. And the men in the shipyards and the women spinning in the factories of New England were thinking on the World’s Fair. And in the sun-loved South the laborers in the tobacco, rice, cane and cotton fields were telling one another of the wonders that are to be. Cowboys on the broad plains of Texas, and gold and silver getters in the mines of the great West dwelt upon the theme of the World’s Fair, while the workers in the vineyards of California whispered the story to the Pacific. I looked toward the frozen North and saw the Alaskans chasing the seal and the Esquimaux harnessing the reindeer. In the snow-swathed lands they had heard of the Columbian Exposition, and in strange tongues were planning to collect curious things for us to look upon.

The Great Japanese Vases. [Image from Kilburn stereoscope card No. 8143.]

Great Britain, busy with her ships and factories, was planning for the World’s Fair, and the French, amid their wines and cassimeres, ribbons and artificial flowers, porcelain and perfumery were turning their eyes Chicagoward. The Germans in their fields and vineyards; the Swiss making watches and wood carvings; the Belgians and the Hollanders fashioning lace and velvets, carpets and cutlery; the Austrians making wine and leather goods and glassware; the Scandinavians in mines and forests and fisheries; the Spanish and Portuguese handling raisins, almonds, oranges and lemons; the Italians busy with statuary, silks, olive oil and fruits; Greece tending her flocks and fields and grasping after her departed greatness; all were looking toward the spot that is to be the Mecca of the world in 1893. Mexico, Central and South America were turning their faces to the north, and wind and wave had carried the news to the farthest islands of the sea. Every human being was interested in the great event that is to commemorate not alone a historical date, but is to mark the world’s progress toward the broader freedom, the grander brotherhood that shall some time come to men.

A lithograph titled “All Nations are Welcome to the World’s Columbian Exposition” shared Waterman’s vision of “the grander brotherhood that shall some time come to men.” [Image from World’s Columbian Exposition Illustrated.]

I awakened from the sleep that had crept over my eyes a few moments before when I had paused to rest in the cool and quiet nook. So the tower and the wonderful spectacles were but a vision in my sleep, but the world-wide scene I saw, “It was not all a dream.”

Nixon Waterman

Chicago, August, 1895

Leave A Comment