One song served as the (unofficial) anthem of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. More popular than “Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay,” more often sung than “America,” and more frequently parodied than “Daddy Wouldn’t Buy Me a Bow Wow,” this tune could be heard—for better or for worse—throughout the fairgrounds all summer. Groups ranging from John Philip Sousa’s band to the marimba quartet at the Guatemala Building to the donkey boys on the Street in Cairo performed the hit of Fair, “After the Ball.”

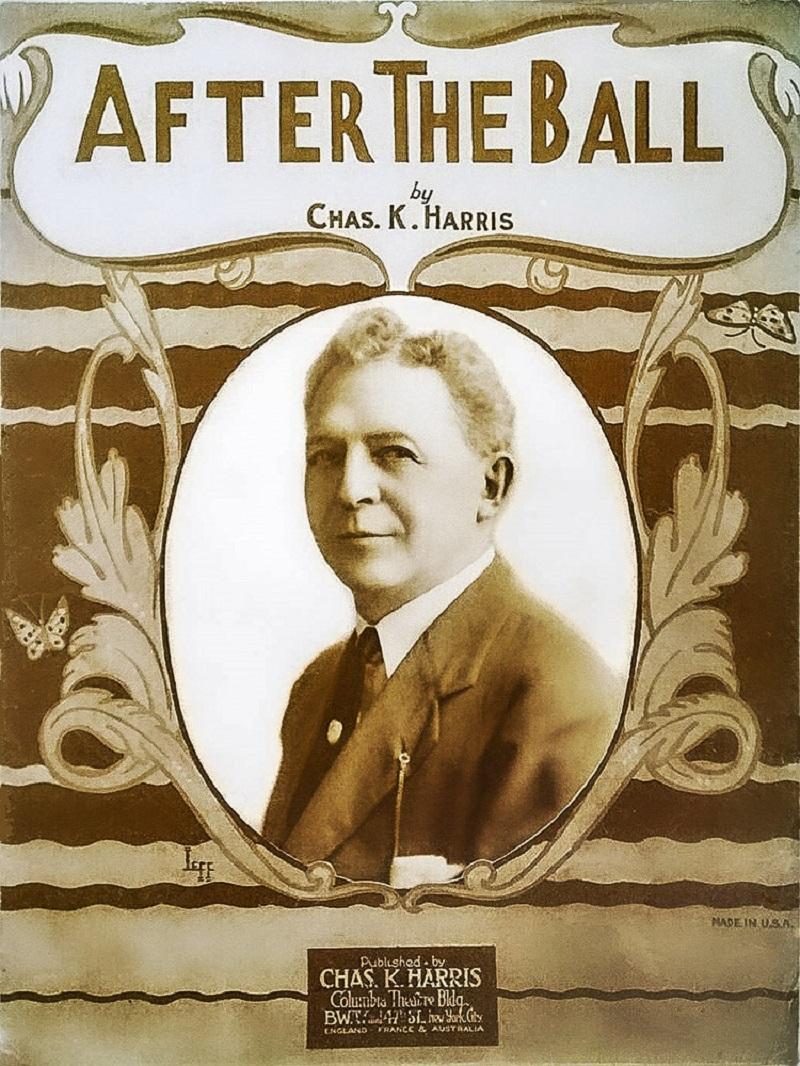

The cover of sheet music for Charles K. Harris’s incredibly popular “After the Ball,” the unofficial theme song of the 1893 World’s Fair.

World’s Fair anthem

That music had its charms to soothe,

The savage breast men once would say,

But that was in the days before

“After the Ball” and “Boom-de-aye.”

—The Chicago Inter Ocean, Oct. 7, 1893, p. 12.

Self-trained musical composer and lyricist Charles K. Harris, from Milwaukee, claimed that he wrote the song in one hour in 1892 when he was twenty-five-years old. “After the Ball” soon became the biggest hit of the “Gay Nineties,” reportedly selling two million pieces of sheet music in 1892 alone. With a profit of sixteen cents on each, Harris was earning $1,000 a day (more than $34,000 a day in today’s dollar!) from his popular creation during the 1893 World’s Fair.

While the verses of “After the Ball” tell a sentimental story of lost love, its catchy chorus was easily adopted for any festivity, including those on the fairgrounds:

After the ball is over,

After the break of morn,

After the dancers’ leaving,

After the stars are gone;

Many a heart is aching,

If you could read them all,

Many the hopes that have vanished,

After the ball.

Portrait of “After the Ball” composer Charles K. Harris [Image from Portland (ME) Daily Press Sep, 1, 1893.]

Music on the Midway

Wandering up and down the Midway

Tom-tom music may appall,

But there’s one thing they’ll not tackle

And that is “After the Ball”

—The Chicago Inter Ocean August, 8, 1893

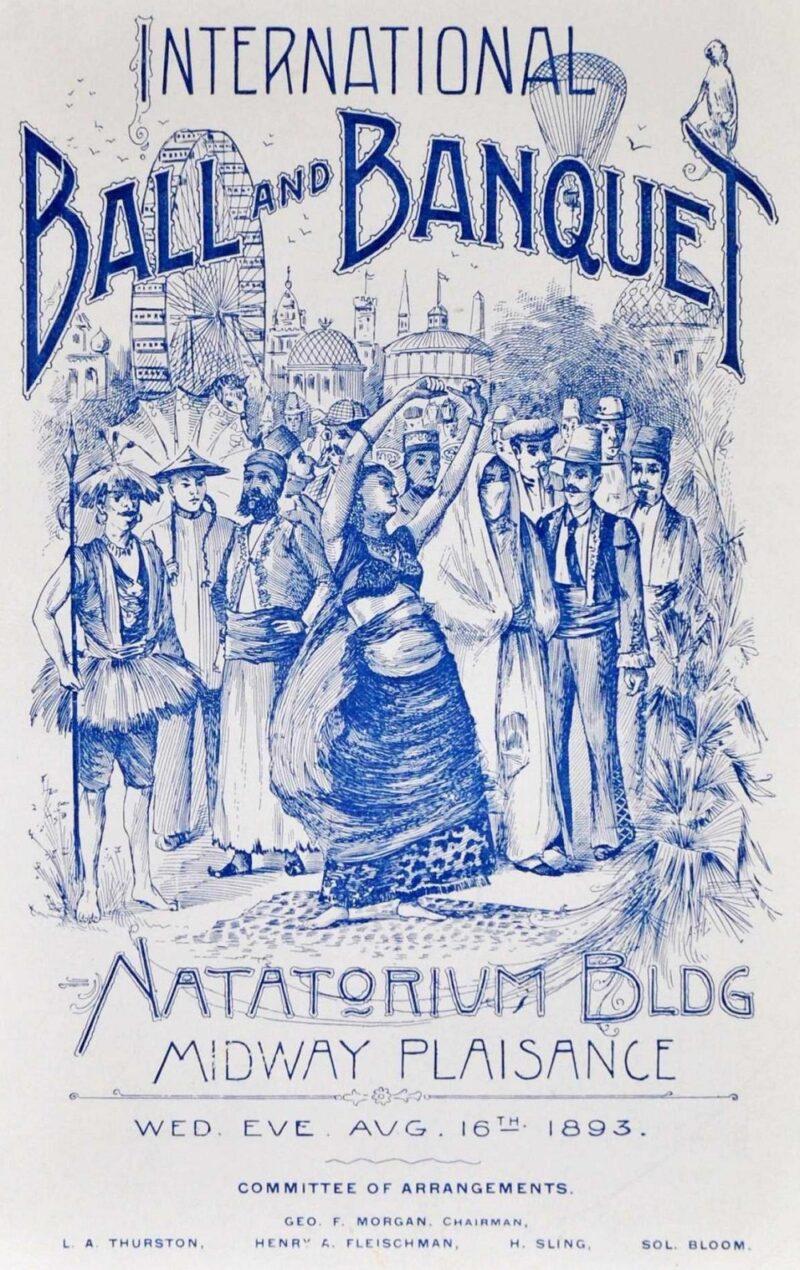

“After the Ball” seemed to explode in popularity around the time of the raucous International Ball on the Midway Plaisance on August 16. In its aftermath, Journalist Teresa Dean resumed her regular visits to the fairgrounds after spending a week in the country. She immediate noticed that “the World’s Fair seems to have flopped over and turned up the brightest, and freshest, and noisiest, and most ambitious side.” She told this story of her visit to the Midway Plaisance:

Within hearing distance was a band of music from the Orient, a brass band in an Irish village, another one in a tented “garden,” and still another in the German village, and all of them were at that minute playing “After the Ball.”

I spent the afternoon on the Midway, and in sauntering along was never without the familiar strains of that ballad from some direction. Everybody recognized it, and everybody seemed to enjoy it.

I overheard a man say that the composer, Charles K. Harris, had made $100,000 out of it. The only rival “After the Ball” had among the Midway bands was “Daddy Won’t Buy Me a Bow-wow.”

The August 16, 1893, International Ball on the Midway Plaisance made “After the Ball” even more popular … and more reviled.

Sour notes

“Insult to Injury”

WILKINS.— Gracious! old man, what State building is that where they let a female Calliope bang the piano and sing “After the Ball”?

TOM ALTO.— That ain’t no State building—that’s the Bureau of Public Comfort.

—World’s Fair Puck Aug. 28, 1893, p. 200.

Not everybody enjoyed the tune, though. A few weeks later, Dean recorded this:

Last evening a man was lifted to the shoulders of several men and carried out from the midst of a throng, and deposited with a sort of dull thud by the roadside. Some one asked what the man had done. A dozen voices shouted:

“Done? He was whistling ‘After the Ball.’”

That settled it.

The melody certainly rattled around the heads of more than few spent revelers staggering out of the International Ball on August 16. The excerpt below, from the Chicago Record on the following morning, describes the side effects of the omnipresent tune.

“Fancy and a Fate Tune”

One objection to the Fair is that there is no place provided for a person who feels that he wants to be poetic and rave over the utterness of it all. A person can’t attain a proper frame of mind in a hurley-burly crowd, and it is out of the question to preserve a train of rapt thought with wheelchairs bumping into one and catalogue boys shouting their wares on all hands.

There was a man of an impressionable nature the other day who simply had to let the attack work itself off, and he rushed to the grand plaza as the most open, less frequented spot. There were not many people there and he tore along, his soul thrilling with unutterable thrills and a grand rapture tumulting within him. He was alone with the glory of the age, he drank it in feverishly, he was glad he lived.

Faint sounds of music came from the distance, but he scarcely noticed them, or if he did madly dreamed they were echoes of the pipings of some classic fawn. The heart of poesy was about him and he was uplifted with it all. The music grew louder and a faint dream of sadness floated down upon him, but it only intensified his spell of happiness. He turned a corner and in one sudden blast the music beat upon his ears, crushed him to the earth, the wings of fancy broken.

“It’s no use, no use,” he groaned helplessly to the sympathizing crowd as the loud streams of a cornet cleft the air in vibrant assertiveness; “I give up—I submit to my fate. This is the third time today that ‘After the Ball’ has intruded itself upon me and it has done me this time sure. Call the ambulance and take me home.”

Thus are brave men slain.

After the ambulance delivered this weary fairgoer home, it needed to head to the Midway for an event more violent reaction to “After the Ball.”

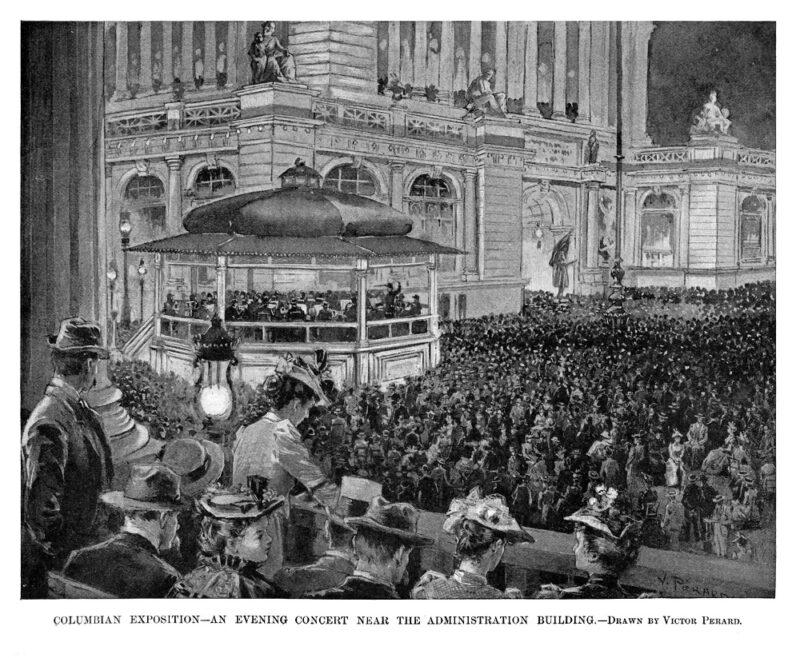

“An Evening Concert near the Administration Building” shows the bandstand where fairgoers could listen to—or run from—concerts of popular music such as “After the Ball.” [Image from Harper’s Weekly Aug. 5, 1893.]

Many a heart is aching

“An Awful Warning”

He was singing “After the Ball”

In the scented garden dim;

A window sash—then a sudden flash—

And the ball went after him!

—Chicago Tribune Oct 8, 1893, p. 30.

It was only a matter of time before someone got shot because of the song.

Two somewhat conflicting news reports in the Chicago Inter Ocean (“Row on the Midway” and “The Cause of it All” on Sep. 27, 1893) describe a fight that broke out on the Midway late in the evening of Monday, September 25. Helen and Ella Blake, accompanied by a Chicago policeman, were patrons of the Mexican Theater inside the (former) Captive Balloon Park. When one of the Blake sisters attempted to sing “After the Ball,” Madge Heath, a dancer in the theater, vociferously objected. A fight broke out when the police officer tried to silence Heath and then knocked her down; pianist “Baron” Van Zedo got involved. Sergeant Gleason of the Columbian Guard was passing by on the Midway when he heard the commotion and entered the fray. When theater manager George F. Morgan grabbed his revolver and fired it into the belligerent crowd, he hit and seriously injured Gleason. All the fighting parties were arraigned the next day in city court … but at least Miss Blake didn’t get to sing the song.

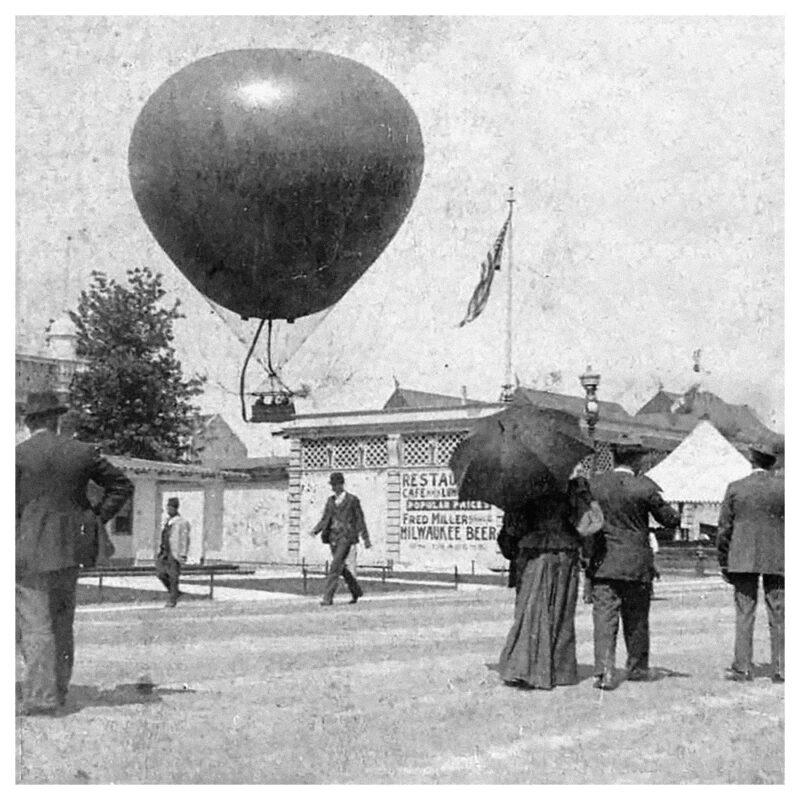

Captive Balloon Park, site of the September 1893 “After the Ball” brawl. [Image from Underwood & Underwood stereoview card.]

After the Fair

“It has become almost as fatal a thing to attempt to recount to another what you saw and did and had done to you at this stupendous collection of the earth’s finest and best as it is to give a whistled expression to that cruelly persecuted melody, “After the Ball.”

—“Rarely Metwith” in The Station Agent, Sept. 1893

On the somber final days of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, one Chicagoan reflecting on the glory of the Fair season shared this thought on the season’s musical infliction:

“You remember we used to avoid the music stands when the bands were playing in them. There seemed to be a sort of sameness in the World’s Fair music. I got to that point where I knew a World’s Fair musician when I met him up-town on the street. Let us go and sit down near a stand somewhere now. I honestly think in an hour like this I could listen to ‘After the Ball’ without any desire to commit a crime.” [“One Man’s Thoughts on Parting” Chicago Tribune Oct. 29, 1893, p.35.] Despite all the disparagement, “After the Ball” remained popular for decades. A film recording of Charles Harris singing his creation has survived, and the song is memorialized by Kathryn Grayson’s performance in the film version of Show Boat (1951).

After the ball is over,

See her take out her glass eye,

Put her false teeth in the basin,

Swallow a bottle of dye,

Put her cork leg in the corner,

Hang up her hair on the wall,

All that was left went to bye-bye,

After the ball.

—“The General” in the Patea (New Zealand) County Mail, Nov. 8, 1897

Leave A Comment