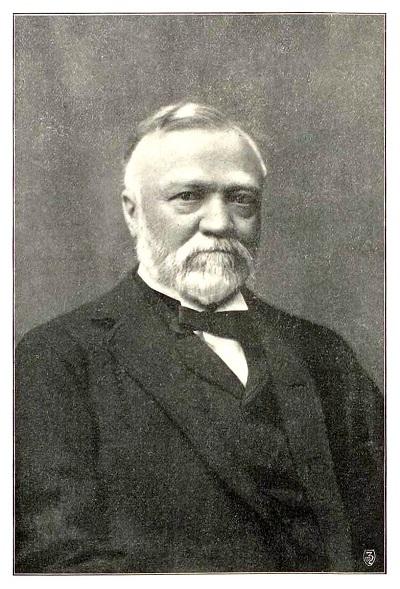

Rags-to-riches immigrant, Gilded Age capitalist, and steel magnate Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919) built bridges and skyscrapers that still stand today. His amassed wealth and radical philanthropy built institutions that should stand even longer—museums and a college for Pittsburgh, a music hall for New York, and thousands of libraries around the world. Carnegie was well on his way in 1892 to becoming the richest man in the world when union-busting efforts and a violent strike at the Carnegie Steel plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania, would tarnish his reputation as a champion of the working man. That his visit to the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago went relatively unnoticed says less about the status of this industrial baron as it does about the sheer volume of celebrities walking the fairgrounds.

Andrew Carnegie and his wife Louise, accompanied by Miss Whitfield (likely Louise’s sister “Stella”) arrived in Chicago on September 22, 1893, and stayed at the Hotel Windermere in Hyde Park. This hotel, built in 1892 for the Columbian Exposition, stood at 56th Street and Cornell Avenue, just across the street from the north edge of the fairgrounds.

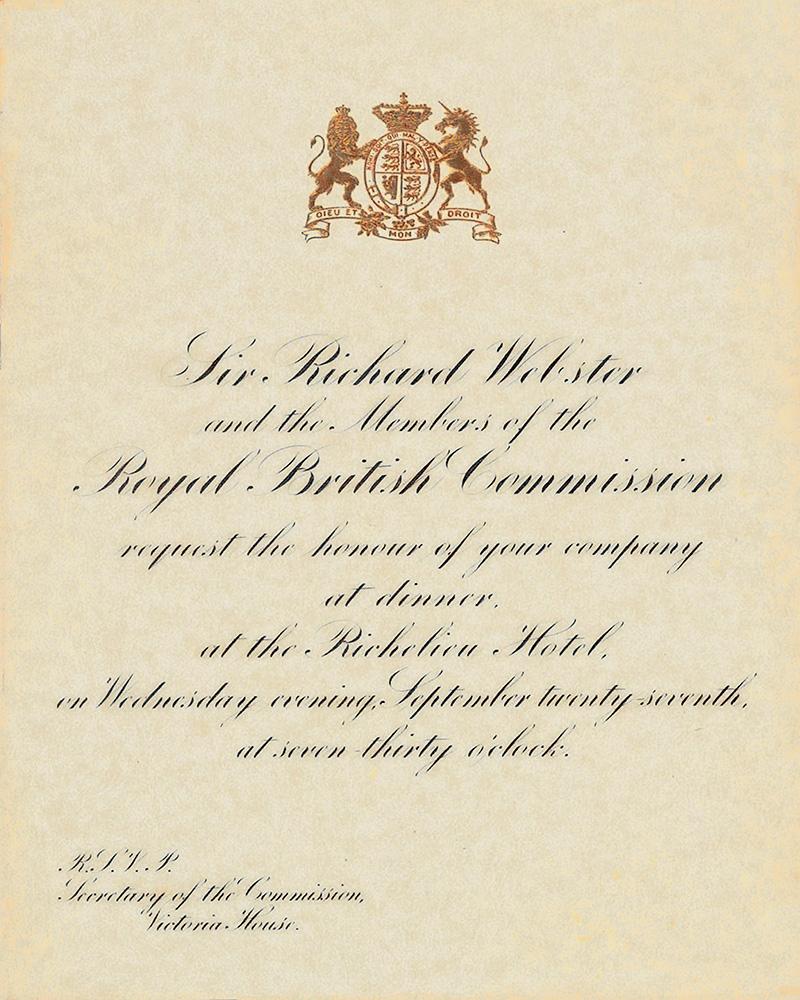

The Carnegies attended receptions given by the Royal British Commission on September 27 at the Richelieu Hotel and the Union League Club the following night. Carnegie had denounced the British monarchical system in his controversial 1886 work Triumphant Democracy, which even features an upended royal crown and a broken scepter on its cover and spine. By 1893, Carnegie was suggesting a political reunification between the United Kingdom and its former colony across the pond, newspapers reported. At these World’s Fair receptions, Carnegie was received by Sir Richard Webster, who served as Queen’s Counsel, member of parliament, and Royal British Commissioner to the Columbian Exposition.

After visiting the World’s Fair, Carnegie penned an introductory essay for a special issue of The Engineering Magazine (January 1894) dedicated to the technical accomplishments of the Columbian Exposition. Reprinted below is his tribute to the Columbian Exposition and its host city of Chicago, “Value of the World’s Fair to the American People.”

An invitation from Sir Richard Webster and the Royal British Commission of the World’s Columbian Exposition for a reception on September 27, 1893. Andrew Carnegie was one of many distinguished guests in attendance.

Value of the World’s Fair to the American People

By Andrew Carnegie

The great exhibition has come, triumphed, and passed away. The unrivalled mass of beautiful structures which seemed rather to have dropped from above than to have been slowly built up from below, are being rapidly dismantled. Our revels are ended. Prospero’s wand has broken the spell. The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces, have dissolved; but the impression made by these greater than Aladdin’s palaces remains, even more vivid than when received. Every one who was privileged to spend days and evenings in windings in and out, through and among the palaces of the White City, and especially to saunter there at night when footsteps were few, has the knowledge to treasure up that he has seen and felt the influence of the greatest combination of architectural beauty which man has ever created.

The universal verdict is that no previous exhibition had ever scored such a triumph. Equally universal is the gratification that it was held in Chicago. When it was decided that the discovery of the country by Columbus should be celebrated, it seemed to be taken for granted at first that there was but one proper place for the ceremony. Soon, however, a second claimant intimated its advantages, but the East was slow to realize that there was anything to be said for the western city. The people of the eastern Atlantic States travel far too little westward. The mention of Chicago as a possible site generally created a smile on the face of the citizens of New York. There were a few, however, from the very first who’ saw that irrespective of the merits of the two cities it was due to the great West that the forthcoming exhibition should be held there. These fair minded people argued that the East had had its celebration in Philadelphia. The revolution in the taste of the people which that display effected was surprising, and the West, it was felt, should have an opportunity to profit through the same means. To day not only do the citizens of New York agree that in every way it was best that the choice fell as it did upon Chicago, but a vast majority go much further and admit that it would have been impossible for New York to equal the success achieved had the exhibition been held there, or indeed anywhere save in the western metropolis,—the center and headquarters of Triumphant Democracy. All honor then to Chicago. Her action throughout entitles her to rank as the most public· spirited city in the world. There are other proofs of her claim to this proud preeminence in the magnificent sums which her citizens vie one with another in providing for the highest wants of a population soon to be numbered by millions. Fourteen millions of dollars given or bequeathed by her citizens are to·day being spent for the good of the city, in patriotic pride of which every Chicago citizen seems to share. Amid much for which this very modern community serves as a model to others let the possession of a salutary civic pride be carefully noted and credited.

The exhibition is closed. What then have been its lessons and its value to the Republic? Others are to give the readers of The Engineering Magazine in detail their replies to this inquiry. Each writer selected for this work is a foremost authority in the branch he is to consider. So eminently qualified are these men for the task that one finds himself looking forward with pleasurable anticipation for their respective contributions to the Magazine. Happily the modest part assigned the writer by the editor is only to give his impressions of the result as a whole, which requires no special knowledge.

A scene of the State Buildings at the 1893 World’s Fair. [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894.]

The notable success of the Chicago exhibition was not material

First, then, the grandest thing about the exhibition was the scene from without. The frame was finer than the picture, and more valuable. The temple viewed from afar was more precious than the temple viewed from within. This is high praise. The first impression of the Taj seen from the garden renders minute inspection of the interior common-place in the extreme. The sight of the Parthenon taught the Greeks more of the beauty in art than anything which it contained. The sight of Edinburgh castle, says Ruskin, influences every Scotch boy who has soul enough to be influenced, and so the dazzling glimpse of that exquisite scene in Jackson Park, the first to greet the eye of the beholder, will be the last to fade from his recollection. I make bold to say that after every work of art, every ponderous engine, every invention. everything that proved the cunning brain and hand of man, has faded away, the general effect of the purely artistic triumph attained by the buildings and their environment will remain, vividly defined in the memory and recorded there unmixed with baser matter. The best reason for heartfelt gratitude and pride is that the notable success of the Chicago exhibition was not material. That our electric display dwarfed what all nations of the earth combined could produce; that our transportation department was a revelation; that the heap of silver, lead, coal, and iron stone was prodigious; that there were temples made of corn, and highly artistic effects produced from cereals, all this was much from one point of view. But from the standpoint of the status of the Republic as a civilized nation, a candidate for supremacy among the nations in the region of art and civilization, these material triumphs pass as a matter of course. We were expected to excel, in these. The grand point is, that incontestable as was our success in these material things, it was yet not so strangely or so unexpectedly incontestable as our triumph in the higher realm of artistic development. “Sir,” said an eminent Frenchman, “these buildings at Chicago seem as if they must have been produced by us in Paris, and those that we boasted of in Paris seem now as if they must have been designed and erected in Chicago.”

The “the heap of silver, lead, coal, and iron stone was prodigious” inside the Mines and Mining Building of the at the Columbian Exposition. [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894.]

The best paintings of American artists

There are three points upon which the success in art was surprising. One I have indicated—architecture: the design and grouping of the buildings themselves, especially in connection with the utilization of the water, which made the scene unique. In sculpture some very notable works appeared. The chief successes in statuary were, of course, in the groups upon and around the buildings, but the work exhibited within was in some instances very remarkable. The American school of sculpture has established itself through this exhibition.

In another department of art the surprise was even more complete. I refer to the American school of painting. There has never been brought together before such an array of the best paintings of American artists. It must, of course, be remembered that the foreign pictures were not of the best, while the American were of the very best; but even keeping this in mind, the result of careful and repeated examinations made by many experts was that even with the best of the foreign modern masters the best of the American modern pictures would hold their place. One American collector was able to exhibit so great a number of the gems of the collection that I could not help envying his position. I did not know anyone connected with the entire exhibition who can more truly be considered a public benefactor than this artistic gentleman, who has evidently for many years had faith in the genius of his countrymen, and has quietly purchased the best examples of their work as these came forth.

“There has never been brought together before such an array of the best paintings of American artists” as in the Palace of Fine Arts at the Columbian Exposition. [Image from Jackson, William Henry, Jackson’s Famous Pictures of the World’s Fair. White City Art Co., 1895.]

A cheering sign of progress

Many congresses assembled in Chicago upon the invitation of the exhibition authorities. Only one of these, I think, is destined in the future to affect the stream of tendency to any great extent. This is not said to disparage any other assembly, because every little aid to a good cause helps. But the Parliament of Religions was an original idea. Never before have the representatives of the various and different religious beliefs appeared upon a common platform upon terms of perfect equality to explain and support their respective forms of belief. That the idea of such a commingling arose, is a cheering sign of the progress the race has made, for within the lifetime of many still living it would have been scouted as almost blasphemous. It is not so very long ago that we western people modestly assumed that we alone had the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, and that the Unknown had kindly favored us to the exclusion of the vast majority of his creatures. To day, it seems that the various sects of Christianity are ready to believe that an all-merciful creator feeds his people, whom he has created in the various lands of the world, with the food which he thinks they are severally best adapted to receive and assimilate for their good. It was a notable sight to see the devout worshipper of the East explain to his rather egotistical brother of the West that the heathens have not been left without heavenly guidance. I wondered that some of our own people did not quote Matthew Arnold’s appropriate lines to prove that the Christian poet was not less advanced than these heathens in the view which they take of the wisdom and care which the Father of all takes of all his children. Christian and pagan could have united in reciting these lines:

“Children of men! the unseen Power whose eye

Forever doth accompany mankind.

Hath look’d on no religion scornfully

That men did ever find.

Which has not taught weak will how much they can?

Which has not fall’n on the dry heart like rain?

Which has not cried to sunk, self-weary man,

Thou must be born again.”

The Parliament of Religions may be credited with having set in motion many forces tending to the harmonizing, and ultimately to the unifying, of the principal forms of religious belief. At all events, it seems to render the differences between the various sects of Christianity much smaller than they were before.

Swami Vivekananda (center) and other East India Delegates to Congress of Religions at the 1893 World’s Fair. [Image from Pictorial Album and History of the World’s Fair and Midway (Harry T. Smith & Co., 1893).]

Brought into close and intimate relation

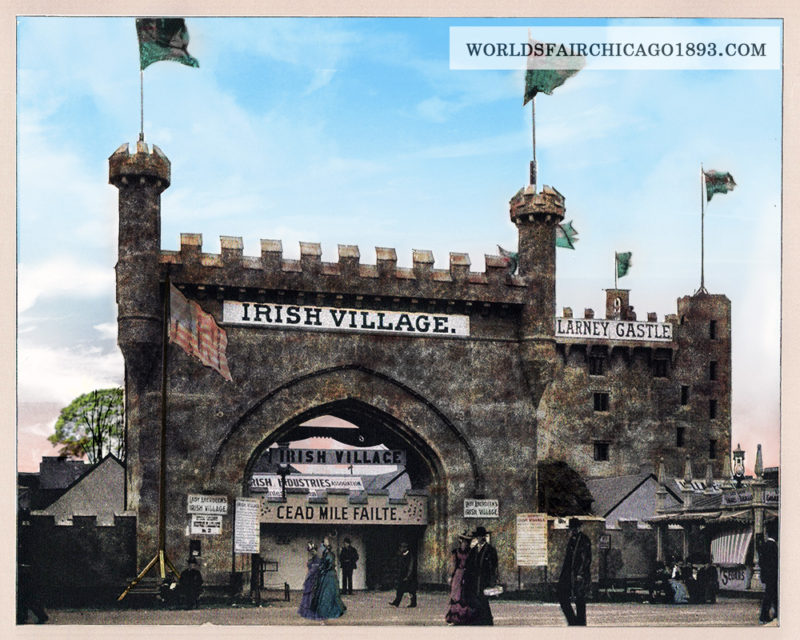

The favored traveler who had done the sights of the world was disposed to jeer at the Midway Plaisance, but I doubt if any department of the exhibition gave as much pleasure and even instruction to as great a number as this unique feature did to the vast majority who cannot hope to travel abroad. The Javanese village, the Street in Cairo, the German village, and even the sight of the reproduction of Blarney castle and many other national scenes were object lessons which gave the best possible substitute for personal inspection of the original. The longing of the American to visit the older countries of Europe is as general as it is strong, but only about 30,000 out of 65,000,000 people go abroad yearly and fully one-half of these have been before, so that not more than 15,000 fresh visitors go each year. Consequently only a very trifling percentage of the whole mass can ever see with their own eyes the scenes about which they read so constantly. None of the arrangements of the managers of the Chicago exhibition seem to have been wiser than the bringing over of correct representations of the lives and homes of the various peoples of Europe and Asia.

The reproduction of Blarney Castle in the Irish Village on the Midway Plaisance. [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894.]

Good manners, temperance, and kindliness

From a national point of view, the chief good from such an exhibition as we are just now considering arises from the gathering together of the people of the different sections. The few who travel much fail to remember that the masses of the people travel but little. Their reunions are confined to the immediate neighborhood. At the most, a State fair draws them together from the same State; but at Chicago the citizens of different States, with their families, were brought into close and intimate relation. Every citizen became not only prouder than ever of his country, of whose position and greatness the exhibition was the outward and visible symbol, but he became acquainted for the first time, perhaps, with his fellow countrymen of other States.

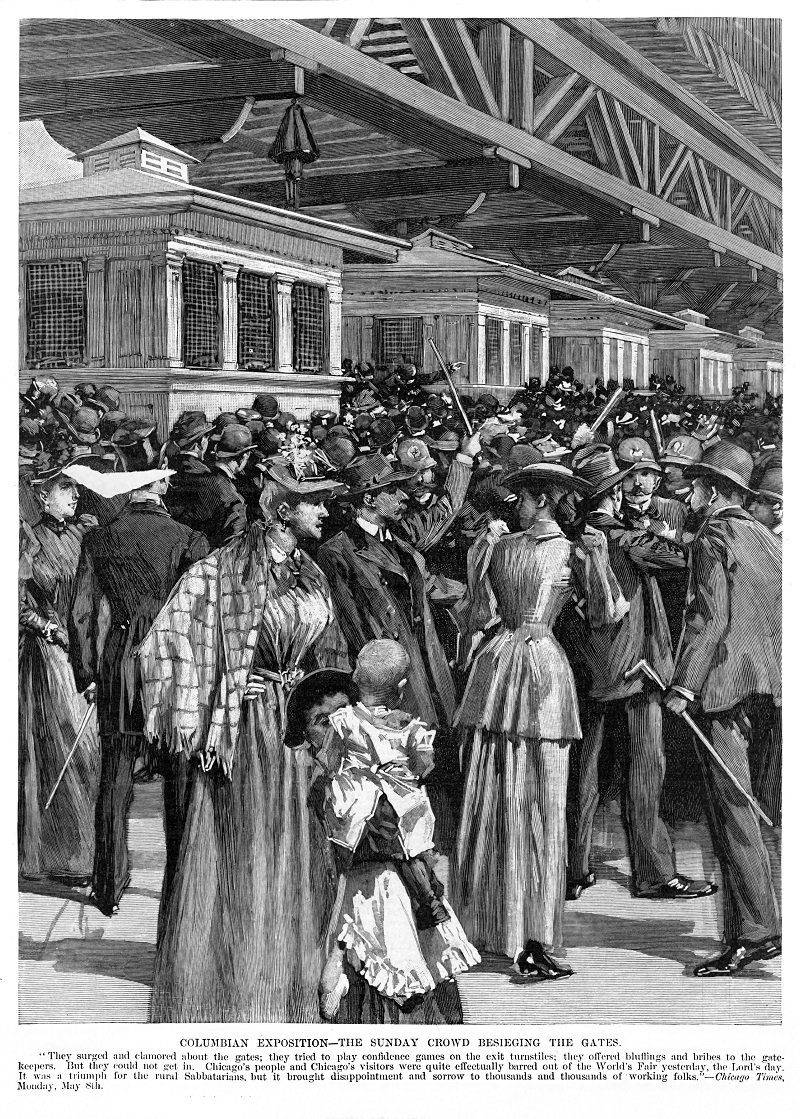

The impression made by the people en masse was highly complimentary to the American. I never heard a foreigner give his impression who failed to extol the remarkable behavior of the crowd, its good manners, temperance, kindliness, and the total absence of rude selfish pushing for advantage which is usual in corresponding gatherings abroad. The self-governing capacity of the people shone forth resplendently. The foreigner’s verdict is that without official direction or supervision every individual governed himself and behaved like a gentleman. So much for universal education.

Carnegie praised “the total absence of rude selfish pushing.” Such courteous behavior was not always observed, as in this scene of “The Sunday Crowd Besieging the Gates.” [Image from Harper’s Weekly, May 20, 1893.]

A work of infinite importance

In a federation so extensive as ours this drawing together of the people of the States is a work of great difficulty, and yet it is of infinite importance, for the masses of the people should not grow up without having in their midst living links who have met their fellow-citizens from other States and found them much like themselves, and in harmony upon one point at least,—their intense Americanism. Every plan should therefore be encouraged which draws the people of the different States together, and an exhibition like that just held at Chicago is by far the most efficacious of all modes. The seventeen years that passed between the Philadelphia exhibition and that at Chicago was a period quite long enough. At least once every twenty years the people should be induced to gather from all the States as they did at Chicago, and, if possible, each section of the Union should be favored by having this national reunion—East and West, North, South, and Center.

Meanwhile let every citizen for himself, and every State for itself, and the Union for the nation as a whole, cherish a deep sense of the invaluable service rendered to the Republic by the people of Chicago, our “Western metropolis,” of which no American can hereafter fail to be proud. It undertook a great task, encountered unexpected difficulties, surmounted all obstacles, and ended by giving the world its most notable exhibition.

Leave A Comment