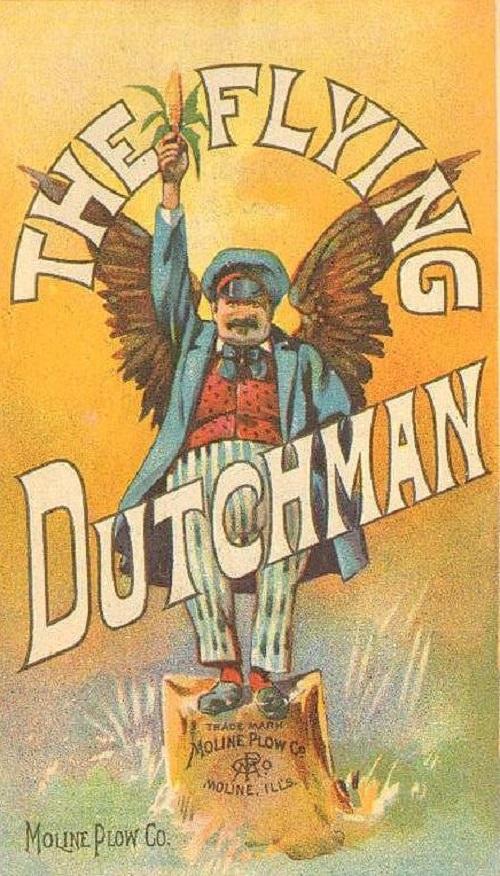

Visitors to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago who found their way into the southwest corner of the Agricultural Building Annex encountered a most curious figure. Rising above a display of farm plows stood a twelve-foot-tall, pot-bellied man flamboyantly dressed and having a pair of huge wings. He stood on a tree stump holding a luminous ear of corn, striking a pose that lampooned the famous Liberty Enlightening the World (aka the Statue of Liberty) by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi. He was The Flying Dutchman, a copper statue promoting the Moline Plow Company.

The copper statue of The Flying Dutchman, advertising the Moline Plow Company at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. [Image from Metal Jun. 1, 1893.]

A typical Dutchman

This “striking and amusing feature of the exhibit,” wrote The Manufacturer and Builder journal, “is made of heavy sheet copper …. The ear of corn in the hand of the grotesque figure is perforated, and so contrived that an electric light enclosed in it may shine through the openings.” A report in the journal Metal described the whimsical figure as “a typical Dutchman with protuberant abdomen, short waistcoat, flaming necktie, Dutch cap and companionable pipe, arranged to personify Liberty holding aloft the light of the world, and decked with eagle’s wings.” He was mounted on “a stump of generous proportions, about the roots of which plants and flowers are growing, while near the middle is placed the trademark monogram of the company.” With its six-foot-high tree stump, the entire Flying Dutchman statue stood eighteen-feet tall.

Attracting much notice while on display at the 1893 World’s Fair, this bronze statue was a three-dimensional version of the company’s trademarked mascot, “an embodiment in metal of what had only before been shown in the printer’s art.”

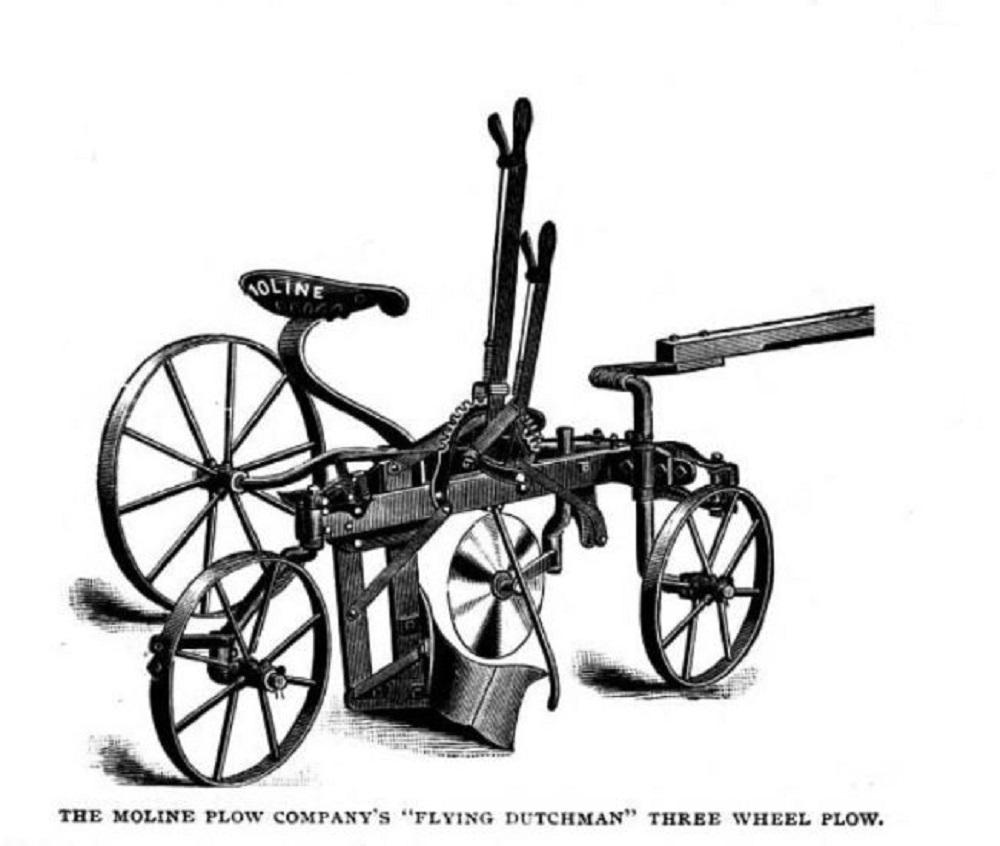

The Moline Plow Company’s “Flying Dutchman” sulky plow that they promoted using their whimsical trademark. [Image from Ardrey, Robert L. American Agricultural Implements. Robert L. Ardrey, 1894.]

The ludicrous trademark

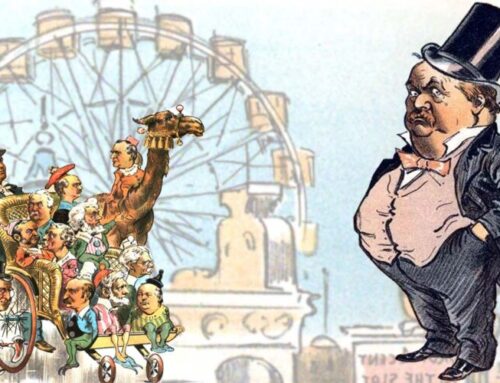

Incorporated in 1870, the Moline Plow Company of Moline, Illinois, at one time was the fifth largest manufacturer of farm implements in the world. One of the products driving the company’s greatest growth was the release of its “Flying Dutchman” three-wheel sulky plow in 1884. This farm implement won an award at the 1893 World’s Fair in the Agriculture category.

The Flying Dutchman statue was based upon lithographic prints of the figure that the Moline Plow Company widely distributed at the time. The secretary of the company, Mr. G. A. Stephens, explained the conception of their “ludicrous trademark” image to the editors of Metal magazine:

“Some years ago we conceived the idea of a new form of plow, which entirely revolutionized the riding plows of the day. So great was the rout of the two wheeled sulky plows that we conceived the idea of naming our plow after the phantom ship, ‘The Flying Dutchman,’ the sight of which, you will remember, created a panic in the hearts of all of the slow going sailors who were unfortunate enough to meet it. From the name ‘Flying Dutchman’ we evolved the present trade mark. In explanation of the poise, we first printed headlines parodying the Bartholdi Statue, from which in part the idea is conceived, to wit: ‘We take the LIBERTY OF ENLIGHTENING THE WORLD of the merits of the celebrated Flying Dutchman Sulky Plow,’ being a play on the words, ‘Liberty Enlightening the World.’ The trade mark has been so taken that we have enlarged upon it and continued to use it generally. This history is interesting as showing the evolution of an idea which began with the famous legendary ship and ends with a gigantic statue so grotesque as to be in itself much more effective for advertising purposes than the original Flying Dutchman could possibly have been.”

Some pundits did not understand the design. According to the Salem Daily News, the “highest authority on architectural matters in the country,” being American Architect and Building News, had this to say about the mascot:

“What the connection is between a plow and a Flying Dutchman we do not pretend to know, but we will hazard the guess that, inasmuch as one plows the sea without ever seeming to get out of order or having to go into the drydock for repair, it is intended to suggest that the other instrument may successfully tear up the soil through succeeding ages without having to be either repaired or sharpened.”

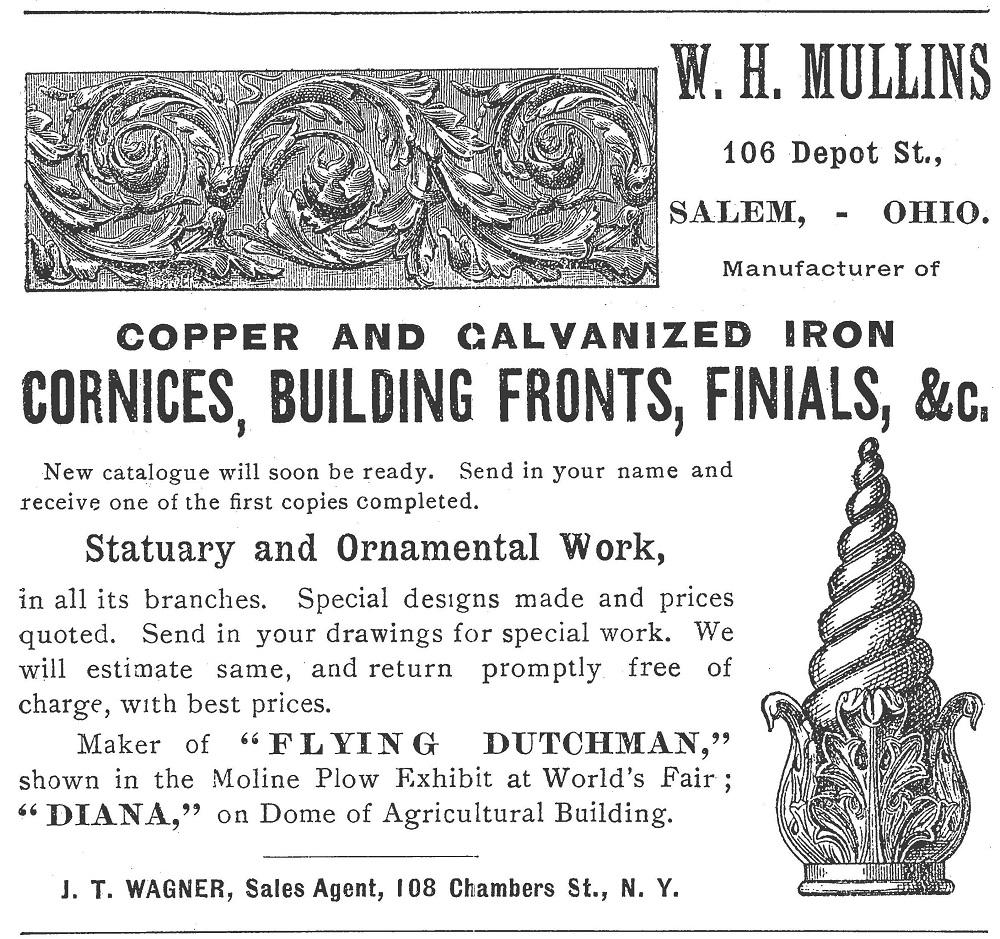

An advertisement for W. H. Mullins highlights their statues of Diana and The Flying Dutchman on the fairgrounds of the Columbian Exposition [Image from The Metal Worker May 24, 1893.]

W. H. Mullins’ Dutchman and Diana

The Flying Dutchman was created in the facilities of the W. H. Mullins Manufacturing Company in Salem, Ohio. The company was known for “allegorical work, emblematic signs and statuary in general.” Other works made by W. H. Mullins also populated the fairgrounds of the World’s Columbian Exposition. The company made several decorative sculptures for Machinery Hall, including thirteen casts in copper of M. A. Waagen’s figure of Victory and four casts in copper of Robert Kraus’ figure of Victory. Mullins also made several identical sheet copper statues of Christopher Columbus by sculptor Alfons Pelzer in 1892; one stood at the entrance to the ill-fated Cold Storage Building on the fairgrounds.

W. H. Mullins’ most prominent work, though, was the eighteen-foot-tall statue of Diana designed by sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Originally placed on top of Madison Square Gardens in New York in 1891, the alluring female hunter was moved to the rooftop of the Agriculture Building for the 1893 World’s Fair. (In 1937, W. H. Mullins merged with Youngstown Pressed Steel under the new name Mullins Manufacturing Corporation. A few years later they introduced porcelain enameled steel cabinets that became known as the popular Youngstown Kitchen line. The company’s metal logo featured on some pieces shows an adaptation of Saint-Gaudens’ Diana sculpture.)

An illustration of The Flying Dutchman statue [Image from White, Trumbull; Igleheart, William World’s Columbian Exposition Chicago, 1893. J. W. Ziegler, 1893.]

Designed to attract attention by its absurdity

A reporter from the journal Metal visited the W. H. Mullins workshop to report on their creation of The Flying Dutchman and came “face to face in the modeling room with a heroic statue.” At that time, sculptor was working on the clay model:

“The artist has very happily caught the idea in every essential particular. A typical Dutchman has been produced; his poise is characteristic, his dress is a truthful reproduction of what obtains with people of his class, and what can be seen on Ellis Island any day when a steamer from any of the Dutch ports arrives. The ear of corn, which typifies the light of the world, is also realistic. It may perhaps be called the light of the prairies. It is Western corn, such as they raise upon the broad and fertile fields of the Mississippi and Missouri valleys, and not a stubby ear of what grows amid the mountains of the Eastern farming belt. That a pair of eagle wings has been made to do service for the angelic idea is due to two facts, first, that because the artist never saw real angel’s wings, and therefore could not reproduce them, as he doubtless would have been glad to do; and, second, because eagle’s wings added to the general combination is only another element to intensify the absurdity of the general composition. Without any definite copy or design, eagle wings are quite as good as any other wings, if wings, indeed, are necessary. This statue, realistic as it may be in some of its features, has been designed to attract attention by its absurdity and because of its burlesque features. As such a work it is a success and has been most happily wrought out by the artist and model maker.”

“Some may, perhaps, be inclined to criticise the proportions of the figure,” wrote The Metal Worker, “but we would state in this connection that the idea is to represent a burlesque rather than a figure of strictly accurate outline.”

This sculptor employed by W. H. Mullins to create the clay model was A. Pelzer, according to The Monumental News. The eighteen-foot copper statue “will be painted in natural colors,” the news outlet also reported. “The statue which will doubtless be quite picturesque will be placed in the exhibit of the Moline Plow Company at the World’s Fair.”

Mr. Pelzer “evidently deserves a place somewhere on the ladder of fame,” reported American Architect and Building News, “as he has discharged his task with marked success. The final statue was sculpted from a beaten sheet of thick copper. “It seems not too unlikely that as a business venture he will derive more profit through the exhibition of this figure, which will certainly be remembered by all who see it, than if he should merely state that the figure of Diana and the sundry angelic and cherubic figures on the machinery building had been produced at his works.”

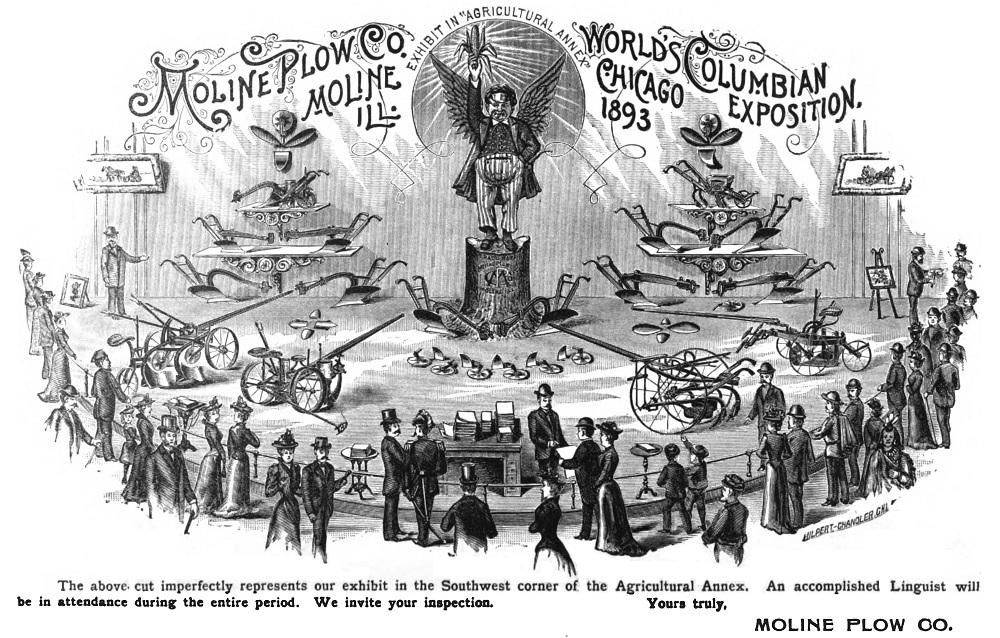

The display of the Moline Plow Company in the Agricultural Building Annex of the 1893 World’s Fair featured its Flying Dutchman copper statue. [Image from Handy, Moses P. The Official Directory of the World’s Columbian Exposition. W. B. Conkey, 1893.]

Show to the best advantage

As early as March of 1893, newspaper reports described plans for the Moline Plow Company display at the great fair. “The principal attraction,” wrote the Davenport Daily Times, will be the copper Dutchman statue “who will take the liberty to enlighten the world in regard to the merits of the plows by which he is surrounded. The plows, planters, cultivators, etc. will be grouped about this statue in such a manner as to show to the best advantage.”

Columbian Exposition historian Hubert Howe Bancroft wrote of the display: “The Moline Plow company of Illinois, with one of the largest factories of the kind in existence, has a spacious pavilion, the central figure of its exhibit being a mammoth bronze statue of a Dutchman, with outspread wings, typical of its Flying Dutchman sulky plough.”

Perhaps anticipating interest from international visitors at the Fair, a company advertisement promised that “an accomplished Linguist will be in attendance during the entire period. We invite your inspection.”

A paper Flying Dutchman advertisement.

The Dutchman sinks

In the years after the Fair, the design of the Moline Plow Company’s amusing mascot evolved, with small changes made to his outfits and poses. Sometimes his wings and torch were removed. The figure appears in a wide assortment of advertising products.

While the lad from German folklore endured these alterations to his pants and stance in the early part of the twentieth century, politics eventually imposed the biggest change. The Minnesota History Center reports that “The Dutchman’s reign ended in 1917, when anti-German feeling during World War I caused Moline to abandon the pot-bellied trademark.”

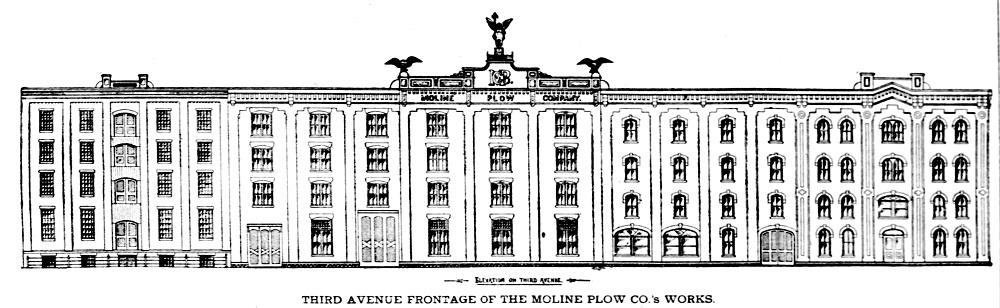

The new Moline Plow Works building built in Moline in 1897 featured the Flying Dutchman statue from the 1893 World’s Fair. [Image from the Moline Dispatch Aug. 7, 1897.]

What happened to the statue?

After the close of the World’s Fair in Chicago, the Flying Dutchman statue sailed to the company home in Moline. He made a occasional appearances, such as in the 1894 Labor Day parade in nearby Davenport, Iowa. When the company constructed a new building in 1897, the copper statue served as “a central point on the Third Avenue frontage on the top of the main wall,” reported the Moline Dispatch. He was flanked by a pair of six-foot eagles, also made by W. H. Mullins.

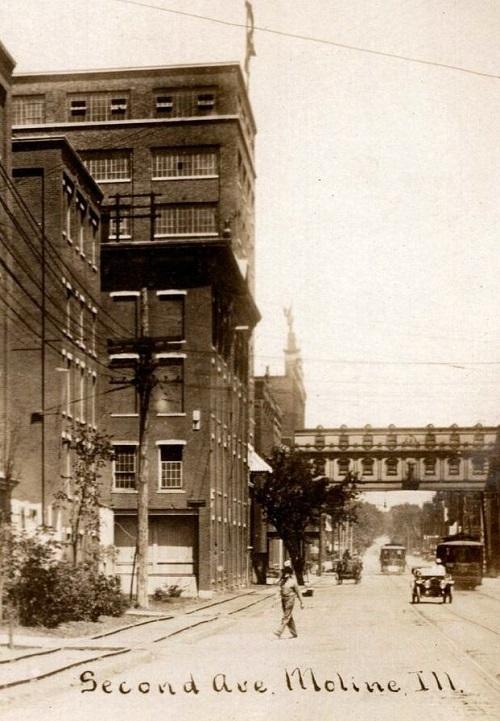

A Moline Plow Company factory postcard c. 1910 showing the Flying Dutchman statue still on the roofline.

A postcard from circa 1910 depicting a street-level view of the Moline Plow Company factory campus appears to show the World’s Fair remnant still atop one the buildings facing Third Avenue (now River Drive). The Flying Dutchman certainly would have come down by the time John Deere purchased the company and property in 1959, if not much earlier.

While many reproductions of the famous Moline Plow mascot were manufactured over the years, all appear to be of smaller dimensions and made of different materials. For example, handsomely painted Flying Dutchman statues in the collections of the Minnesota History Center and Hennepin County Historical Society are far smaller than the original statue.

The fate of the whimsical, eighteen-foot-tall copper man with the corncob torch from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition—and last seen on River Drive in Moline—remains a mystery.

* * * *

Anyone having additional information about what happened to the original Flying Dutchman copper statue is encouraged to post in the comments below or email us using the “Contact Us” link in the “About Us” tab at the top of the page.

UPDATE

A reader sent us another image that shows the Flying Dutchman statue on the roof of the Moline Plow Company factory c. 1910, a photograph shot from the opposite direction:

SOURCES

Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.

“The Dispatch says … Davenport (IA) Daily Times Mar. 31, 1893, p. 3.

“Copper Statue Flying Dutchman” Scientific American Building Monthly July 1893, p. 13.

“The Flying Dutchman” The Manufacturer and Builder Aug. 1893, p. 1.

“The Flying Dutchman” Metal Jun. 1, 1893, p. 338.

“The Flying Dutchman” Salem (OH) Daily News Jul. 3, 1893, p. 7.

Handy, Moses P. The Official Directory of the World’s Columbian Exposition. W. B. Conkey, 1893.

Minnesota History Center https://www.mnhs.org/historycenter

“The Plow Co. Building” Moline (IL) Dispatch Aug. 7, 1897, p. 5.

“The Story of a Trade Mark” Metal Jun. 15, 1893, p. 430.

“A Trade-Mark in Sheet Metal” The Metal Worker Jun. 10, 1893, p. 37

“World’s Fair Notes” The Monumental News April 1893, p. 174.

Leave A Comment