“The Columbian Exposition had a decidedly reformist influence,” writes World’s Fair historian Reid Badger, “and there is little question that it was at least an indirect factor in the development of the ‘City Beautiful’ movement.” [Badger 115] Among the great urban planning pioneers influenced by the 1893 World’s Fair was Charles Mulford Robinson (1869–1917).

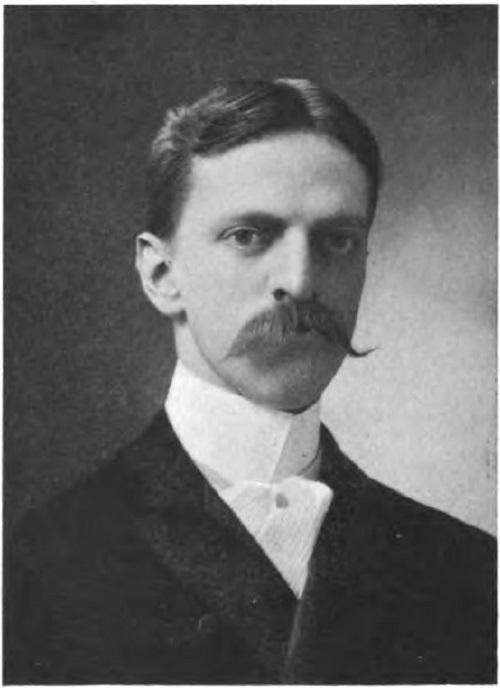

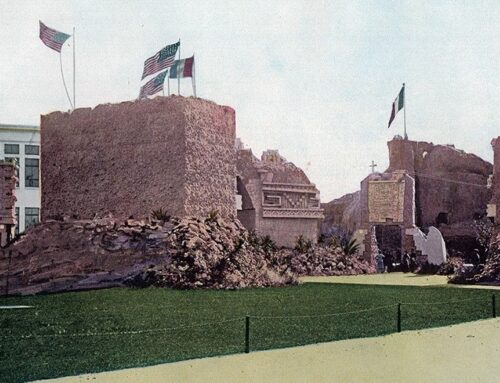

Urban-planning pioneer Charles Mulford Robinson memorialized the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in his essay “The Fair as a Spectacle.” [Image from Johnson, Rossiter A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Held in Chicago in 1893, Volume 1: Narrative. D. Appleton and Co., 1897.]

With visions of harmony still dancing in his head, Robinson wrote a series of articles on “Improvement in City Life” published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1899. In the third installment, he reflected on the influence that the Columbian Exposition had on urban planning:

“During the summer and autumn of the world’s fair at Chicago, when the country was carried away by the exposition’s unexpected beauty, it was common to hear it spoken of as ‘the white city’ and ‘the dream city.’ In these terms was revealed a yearning toward a condition which we had not reached. To say that the world’s fair created the subsequent æsthetic effort in municipal life were therefore false; to say that it immensely strengthened, quickened, and encouraged it would be true. The fair gave tangible shape to a desire that was arising out of the larger wealth, the commoner travel, and the provision of the essentials of life; but the movement has had a special impetus since 1893.”

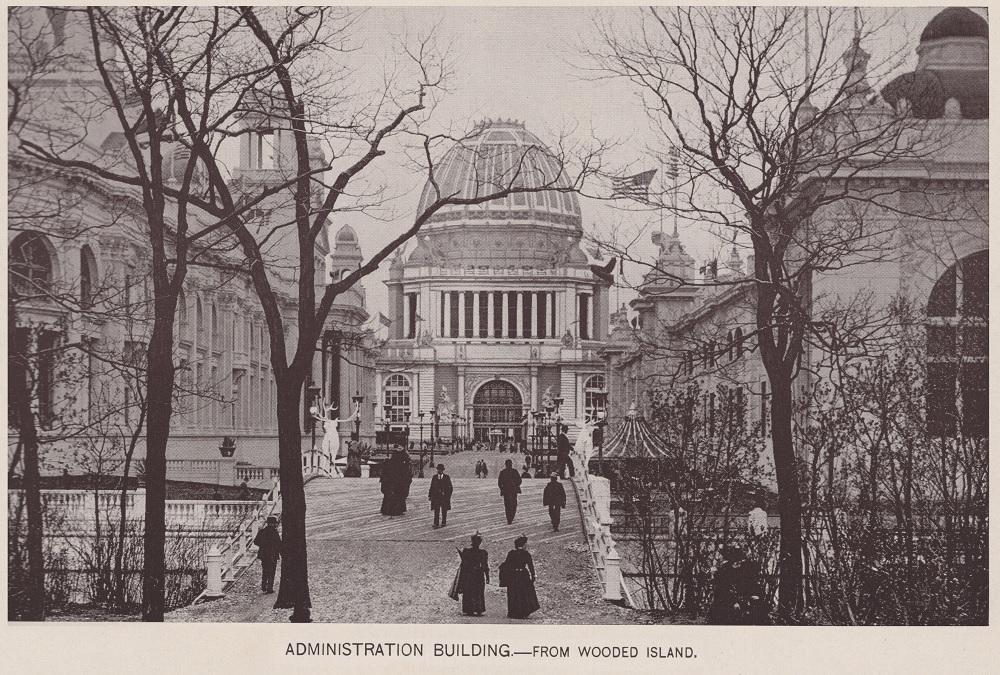

A scene of the “Dream City” showing the Administration Building, designed by Richard Morris Hunt, from the picturesque Wooded Island at the 1893 World’s Fair. [Image from Arnold, C. D.; Higinbotham, H. D. Official Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Press Chicago Photo-gravure Co., 1893.]

His landmark study The Improvement of Towns and Cities (Putnam, 1901) became known as “the bible of the believers in the city beautiful.” At the time of Robinson’s death, Landscape Architecture Magazine (July 1919) celebrated his important work as “a simple, earnest, straightforward statement of the far-reaching value, and some of the many possible ways, of creating more beautiful civic environments.” The lasting influence of the Chicago Fair runs through his career as an urban planner and is embedded in beautiful city designs still visible today from coast to coast.

The movement toward harmony and orderliness in municipal planning, he claimed, reaches back to the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, “the great popular object-lesson in the value of extensive cooperation, in the placing of buildings and their landscape development as strictly as in their architectural elevation. The lesson was international in its effect, exerting an influence that has appeared over and over in many lands …” [Robinson, Modern Civic Art, 275]

Charles Mulford Robinson’s eloquent “The Fair as a Spectacle” serves as the closing chapter of Rossiter Johnson’s monumental A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Held in Chicago in 1893, Volume 1: Narrative. The original text has been divided into four parts (with added section titles); minor typographical and spelling errors are corrected. Additional images to complement the text. Robinson’s text contains some racial terms now considered offensive. They remain in this reprint for historical accuracy, but which were common at time and in the society in which this work was created. Please consult our statement on “Potentially Offensive Text and Images.”

Part 1: “Behold my grandeur!”

Part 2: In Search of the Picturesque

Part 3: An Enormous Whirligig of Pleasure

Part 4: A Transformation Scene

SOURCES

Badger, Reid The Great American Fair: The World’s Columbian Exposition & American Culture. Nelson Hall, 1981.

Robinson, Charles Mulford “Improvement in City Life: III. Æsthetic Progress” Atlantic Monthly June 1899, pp. 771–78.

Robinson, Charles Mulford Modern Civic Art, Or, the City Made Beautiful. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904.

Robinson, Charles Mulford “The Fair as a Spectacle” in Rossiter Johnson A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Held in Chicago in 1893, Volume 1: Narrative. D. Appleton and Co., 1897, pp. 493–512.

Leave A Comment