As the daughter-in-law of Chicago Mayor Carter Harrison, Sr., Edith Ogden Harrison had a front-seat view of the 1893 World’s Fair. Born in New Orleans on November 16, 1862, Edith married Carter Harrison, Jr. in 1887. While he walked in his father’s footsteps, serving as mayor of Chicago from 1897–1905 and 1911–1915, Mrs. Harrison was prolific author of children’s fairy tales.

Fifty-six years after the close of the Fair (and the tragic assignation of her father-in-law in his home), she had nothing but fond memories of her magical time on the fairgrounds. In her autobiography, Strange to Say: Recollections of Persons and Events in New Orleans and Chicago (A. Kroch, 1949), Edith Ogden Harrison wrote:

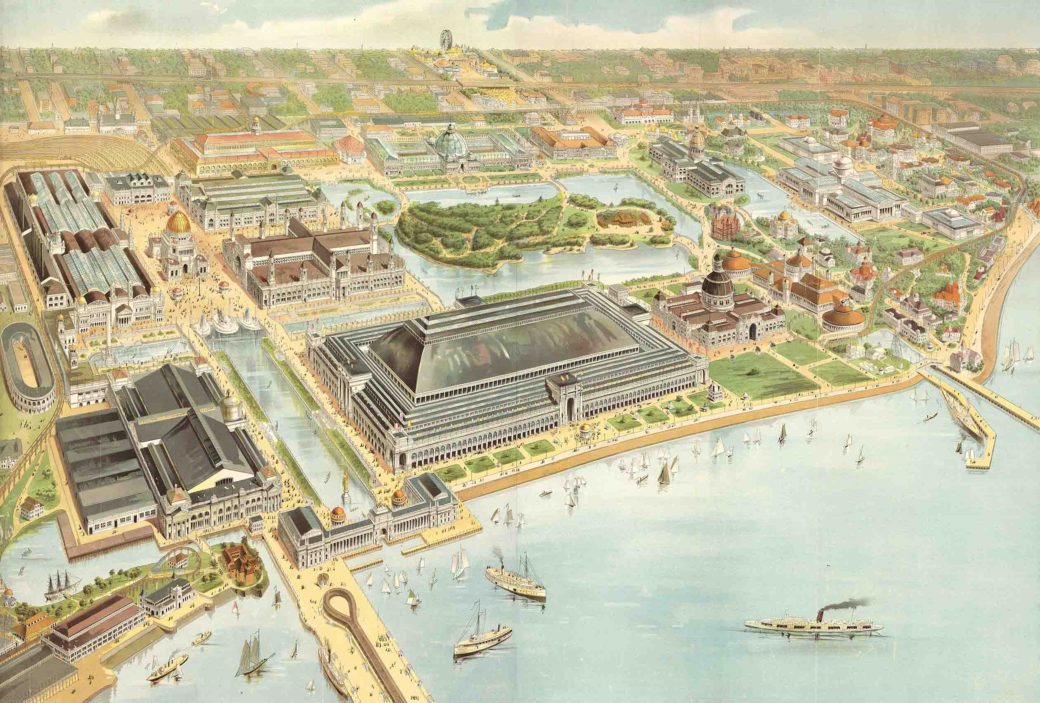

It was a sight as beautiful as it was bewildering. The great scenic beauty of the surroundings, the green lawns sweeping to far distances, the laughing blue lake, the snow-white buildings, so beautiful in architecture—I have but to close my eyes to see it still. Now, with the passing of the years, it seems like some rare and beautiful pastel or a bit of glorious old tapestry. …

Would we ever be able to see it all? This was the question we asked ourselves each night when we returned home for a few hours of rest after the strenuous hours of sightseeing during the day. No soldier ever went forth to war more valiantly than the loyal residents of Chicago went daily to Jackson Park, realizing that the summer would be brief, that the six months of the exposition would pass quickly, almost before they were aware. There was a “do or die” look in the eyes of everyone, and during all the period of the exposition the crowds, sometimes so huge as to be terrifying, were friendly, good-natured and happy. …

It was like a kaleidoscope, constantly changing, ever moving, a blazing, colorful panorama, week in, week out. There was not a dull or uninteresting moment, and under and beneath it all was the knowledge that Chicago was not only writing but making history. …

Out of that period we evolved into the Age of Machinery, the Age of Power, the mania for speed. In 1893, however, all these were not. The beautiful art and craftsmanship were all distinctly hand made. Instead of bleating automobiles one recalls with a certain pensiveness the handsome and powerful Arabian horses over which tall, dark-eyed Arabs, men of magnificent physique, watched lovingly night and day. Electricity, now regarded by many as the power back of all things in the universe, was demonstrated as a commercial possibility for the first time at the Columbian Exposition.

One would have to live long to forget the awe and admiration of the throng which, as soon as darkness fell, began congregating about the electric fountain at the 1893 World’s Fair, with its varicolored lights beneath the rippling waters and the spray created by them. It was beautiful, and if today, as we ride along our miles of boulevards, glittering with millions of lights, we feel a bit blasé, just pause and remember that from the log cabin to the marble palace was but two generations.

Leave A Comment