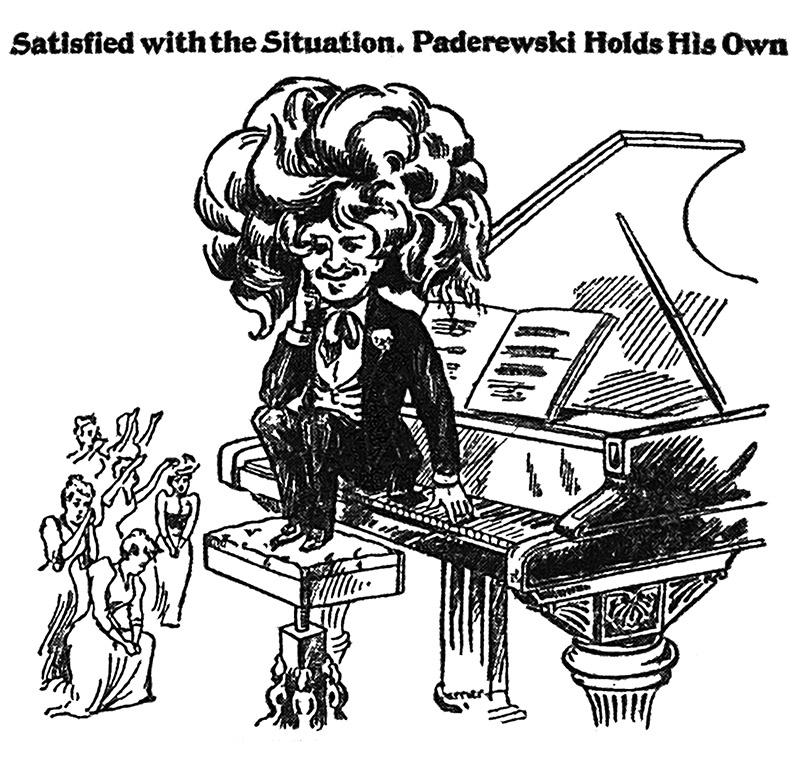

Among the constellation of famous (or soon-to-be-famous) visitors to the 1893 World’s Fair, few stars shined as bright as pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860–1941). Wherever he performed, concert halls filled with passionate and adoring fans.

The musical celebrity with wild and alluring red hair cast a spell over the women in the audience. One pundit, in the days before Paderewski’s concert at the opening of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, diagnosed their craze as “Paddymania.” The Musical Courier provided this description of the new concert-hall “disease” brought to America by the Polish pianist:

“‘My God! his beautiful face haunts! I cannot put it away. Oh, that it would leave me for just a moment so that I could sleep!’ The speaker was a lovely girl, whose set stare, disheveled attire, disordered hair and long fingernails proclaimed to the lookers on that she had fallen a victim to that curious fin de siècle neurotic disorder—alas, raging so furiously in this city at the present moment—Paddymania.”

While the women swooned, the men battled about which brand of piano the artist would be allowed to use on the fairgrounds. Paderewski’s May 2 inaugural concert to open Music Hall provided a coda to a tumultuous few weeks known as the great “Piano War” of the Fair.

The rather sarcastic concert review reprinted below, from the front page of the May 5 San Francisco Chronicle, measures the temperature of the fevered reception given by the “Paderewski girls” on a rather chilly spring night in the White City. [Note that Paderewski used an alternate first-name spelling of “Ignace” in America.]

Adoring women gather beneath Polish pianist Ignacy Paderewski at his concert for the opening of the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. [Image from an advertisement for Kirk’s Soap in the Chicago Inter Ocean on May 4, 1893.]

FROZE WHILE THEY LISTENED

Paderewski Opens Music Hall in an Arctic Temperature

Ignace J. Paderewski has consecrated Music Hall at Jackson Park. He did it yesterday in the presence of the most unique audience he ever faced; a collection of people who shivered and shook in the Arctic blasts, pent up in the building since the time when winter was strong. They sat with their hats on, men and women; buttoned tight their coats, drew up their collars, and ran foot-races in the corridors to keep their toes warm. They applauded with might and main to keep up circulation and chased about to find places which the echoes had not discovered. The folks in the galleries looked like lone fisherman with a section apiece.

Mr. Paderewski did not wear gloves when he was playing. He took them off just before coming from behind the stage. He had not yet doffed his winter clothing, and anyway his vigorous manner would supply him with heat, which the two red hot salamanders did not. The salamanders were part of the stage decorations, sort of central figures, about which green bay trees and azaleas were arranged with more-or-less artistic effect. They did not have any stovepipes, and the out-of-town audience spent the time between the numbers wondering where the smoke went and how he combed that hair.

Mr. Paderewski had a magnificent orchestra to assist him in the consecration, an aggregation of artists selected from music centers. It was a terrific, thrilling mass of instruments that thundered and roared until the very roof and pillars seemed to tremble, and the bronzed and painted lyres to tingle. He had nearly six score players, giant batteries of basses, great cavalcades of wind instruments and violinists until the air was black with deft bows. There was also Conductor Thomas, who rapped his baton with vehemence and slashed the air into chunks. It was the proudest day of his life, and Paderewski and all the rest played with marvelous zest and excellency.

Mr. Paderewski was given a most cordial reception, notwithstanding the fact that the audience enjoyed the distinction of being the smallest before which he has performed in this country during the past two years.

Paderewski played to wildly clamorous women a second time in Music Hall this morning. They came in droves and scores and coughed and sneezed and immolated themselves on the altars of discomfort before their idol. They cried aloud in crazy enthusiasm and vied with one another in the violence of their demonstration. The men laughed. The shriners patted encores until their arms fell from exhaustion and waved handkerchiefs until the air was a mass of fluttering lace and linen. They followed him from the building to the electric launch, and waved kisses at their hero. He stood on the deck like a statue, bowing a most gracious farewell. This was his parting ovation.

Music can soothe the savage breast, but it can’t warm the shivering body, and that is why the popular concert this morning was exceedingly unpopular. It was the first one in a series of free entertainments which promises to be among the finest features of the exposition when summer comes and the sun makes the big Auditorium fit to sit in. The audience was cosmopolitan, with men from the far ends of the earth and others from near at hand. A group of bright-faced mandarins from the Chinese theater company was flanked by a visiting delegation of ultra English nabobs. A company of ecstatic Frenchman annoyed some sturdy Germans who sat in a trance. Stylish Austrians and turbaned Turks elbowed one another, and a line of Japanese filled the front row. Had the weather been a trifle warmer even the men would have enjoyed it.

Leave A Comment