Appetizer: New York’s social dictator

“The real Chicago, which works and hustles and brags about the Fair, cares nothing about McAllister or what he says.”

—The New York World, April 16, 1893

He has been called “New York society’s panjandrum of lavish entertaining,” “a greater official than the mayor, a custodian of the ultra-fashionables,” a “flamboyant and outspoken figure,” the “foremost consultant in pleasure” and a “master of punctilio and snobbery.”

Others named him “the Autocrat of Gotham’s 400,” “Dictator of Society,” “head butler to some of the rich people in New York,” the “Prince of Snobs” and a “mouse-colored ass.”

One of his contemporaries explained that “he is regarded as a mysterious power, whose favor is an ‘Open Sesame,’ or an ogre who stands blocking the way to the enchanting inner circle of New-York society.” [“Secrets of Ball-Giving”] A memorial at the time of his death bluntly described him as “at once the best-liked and the best-hated man.” [Dewey]

Viewers of Julian Fellow’s television series The Gilded Age (HBO, 2022) meet him as the elitist social advisor to Mrs. Astor (two real-life characters on the series) as portrayed by Nathan Lane.

Who was Ward McAllister? How many different ways did he count to 400? Why did he sling condescending advice at the host city of the 1893 World’s Fair? How did Chicago respond?

Ward McAllister, New York’s social dictator, portrayed by Nathan Lane on The Gilded Age (HBO, 2022). The studio notes that “he is chiefly remembered now as the inventor of the phrase, ‘the four hundred.’ This was the number of people who were worth bothering with in New York society. McAllister serves as Mrs. Astor’s right-hand man and his chief business and pleasure in life is help her guard the gates to High Society.”

He set the standards of luxury

“It is very well to have birth, but if you lack that, refinement and culture will replace it.”

—Ward McAllister

Born Samuel Ward McAllister in 1827, the future arbiter elegantarium of New York Society spent his boyhood in Savannah, Georgia. His first taste of the life he desired came when summering in Newport, Rhode Island, with the family of his uncle Samuel Ward, a prominent New York banker. While living for a time in New York with a rich maiden aunt, he learned about the society balls. After graduating from Yale, her returned home to train in his father’s law office in Savannah, passed the bar examination, and started a practice in San Francisco.

His cousin, the author and activist Julia Ward Howe (1819–1910), spoke at the Congress of Representative Women held during the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.

In 1853, McAllister married Sarah T. Gibbons (c. 1830–1909), the daughter of Georgia millionaire William Gibbons. He spent several winters in London, Rome, Florence, Baden-Baden, and Pau, and returned to the U.S. equipped with sophisticated knowledge of wine, haute cuisine, etiquette, and entertainment.

After the Civil War, he moved to New York where he spent the rest of his life as the tastemaker for the city’s “Knickerbocracy,” families of Dutch descent having great wealth and standing. “Society is an occupation in itself,” McAllister claimed. [“Secrets of Ball-Giving”] Admission emphasized birth, background, and breeding more than just wealth. [Churchill, 89] One scholar of the Gilded Age describes McAllister as “a man who would set standards of luxury that would increase the exclusiveness of the rich and surround them with an aura that wealth alone could not achieve.” [Rugoff 81] He aimed to Europeanize the social affairs of New York’s aristocrats.

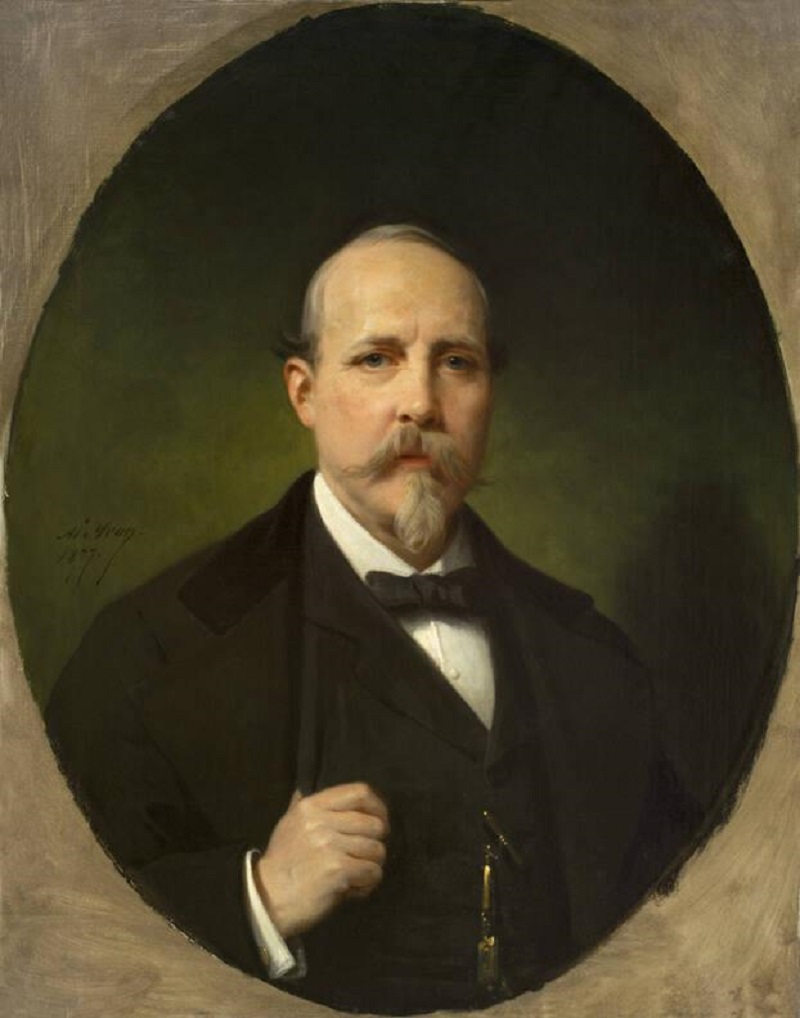

Ward McAllister in 1877, depicted in an oil painting by Adolphe Yvon. [Image from the New-York Historical Society.]

Simply a modest man

“A fortune of a million dollars is only respectable poverty.”

—Ward McAllister

“I have no claim whatever to be the leader of society,” McAllister claimed in an interview. “In the first place, a man to hold such a position must be rich. I am not. I am simply a modest man living on a modest income.” [“Who Is …”] He reportedly maintained his “modest” lifestyle on about $30,000 a year in 1889, (nearly a million dollars per annum today), though the number had shrunk to only $20,000 six years later.

In 1893, McAllister was living comfortably in an unpretentious house at 16 West Thirty-Sixth Street (now, perhaps appropriately, the site of a gastropub), furnished simply but with exquisite taste. Although Mrs. McAllister remained homebound due to health reasons and rarely was seen in public, the couple did entertain small parties in their home. Mr. McAllister, on the other hand, was in constant demand as a dinner guest.

Seeing him walk along Broadway or Fifth Avenue, no one would have suspected him of being the leader of society. McAllister dressed in quiet, dark attire, invariably wearing a high hat and cutaway coat in the street. Journalist Foster Coates observed that “he looks more like a well-to-do merchant or a prosperous broker.” [Coates] At 5 feet 7 inches in height, his well-knit frame supported a large head. Contrasting his ruddy complexion was an iron gray imperial-style mustache. McAllister walked with a peculiar swinging gait, but otherwise there was nothing in his dress to distinguish him from other men of his time and place.

Ward McAllister strolling in New York. “He dressed quietly, always in dark clothes, invariably wearing a high hat and cutaway coat in the street,” reported the Chicago Tribune. [Image from the Chicago Inter Ocean July 16, 1893.]

Rigidly exclusive

“Success in entertaining is accomplished by magnetism and tact, which combined constitute social genius.”

—Ward McAllister , in Society As I Have Found It (1890)

In 1872 McAllister founded the Patriarchs, an exclusive society twenty-five of the most distinguished families of “Old New York” intent on resisting the nouveau riche. The Patriarchs existed solely for the purpose of giving balls, and McAllister ran them. One of his benefactors described the arrangement:

“It would be utterly impossible for all of us to be conversant with the thousand details which must be looked after to make such an affair a success. To be sure, we could hire florists, and band masters, and caterers, but where would you find a man who combined a knowledge of the best in all these lines? That is what Ward McAllister does for his friends.” [“Social Salad”]

“A ball that any one can gain admission to is never attractive,” Mc (as he called himself) quipped to the press, “while one that is rigidly exclusive will make invitations sought for by everybody.” [“Secrets of Ball-Giving”] Ward “Make-a-lister” (as others called him) enforced elegant exclusivity. Only once did he fail to guard the gates. When Miss Elsie de Wolf slipped past his gate and into a Patriarch’s Ball using some else’s invitation, McAllister became the subject of ridicule in the press and jokes on theater stages in town.

One contemporary described him as:

“The only man of his day willing to give his days and nights to the study of heraldry, books of court etiquette, genealogy, and cooking, to the getting up of balls and banquets, to the making of guest lists and the interviewing of ambitious mothers with debutante daughters … These things he came to love as a miser loves his gold.” [Churchill 83]

When socialite Caroline Schermerhorn Astor (Mrs. William Astor) recognized McAllister’s value, she took him in as her counselor and majordomo. He christened her the “Mystic Rose,” and together they became the haughty and feared arbiters of New York Society, determined to fortify it against what they saw as the intrusion of vulgar millionaires multiplying in the city.

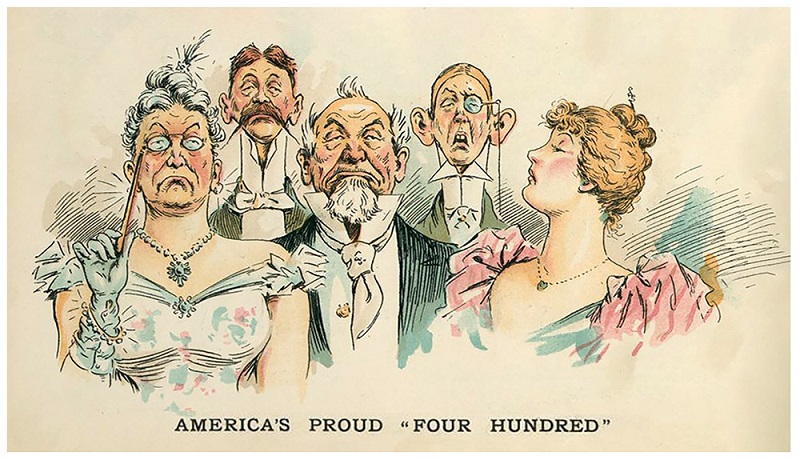

A send-up of “America’s Proud Four Hundred” from the cover of the October 4, 1893, issue of Puck.

Ward Counts the Four Hundred

“Personally, the life of the 400, in its typical form, strikes me as being as flat as stale champagne.”

—Theodore Roosevelt

McAllister also served as press agent to the aristocrats of New York, holding office hours for reporters and feeding them a steady supply of news about the blue bloods. High society’s inner workings became visible to the masses.

During an interview with a reporter from the New York Tribune in 1888, McAllister explained that:

“… there are only about 400 people in fashionable New-York society. If you go outside that number you strike people who are either not at ease in a ball-room or else make other people not at ease. See the point?” [“Secrets of Ball-Giving”]

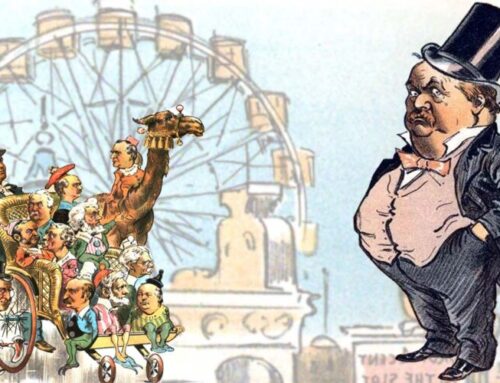

It became the most talked-about number of the era. An appellation synonymous with the Gilded Age entered the American lexicon, earning McAllister a national reputation. The coining of the term “The Four Hundred” was, according to one historian, “perhaps the greatest single American contribution to idea of aristocracy.” [Homberger 4] The term also became fodder for satirical cartoons, topical songs, and comic opera gags.

“The Four Hundred” encapsulated McAllister’s devotion to social discrimination. The line between who was in and who was out had never been so sharply enumerated. “It is a general phrase which stands for an exclusive association of people, who represent the very best society in this city—the aristocracy of New York, as it were,” he stated. [“The Late Ward McAllister …”] By making both the membership and even the number itself somewhat fluid, McAllister wielded enormous power.

Who was on the list? McAllister teased the press with a system of hierarchy made up of 150 “Original Inner Circle,” 19 “Contingent Inner Circle Margin,” 26 “Star Members Inner Circle Fringe,” 49 “Plain Inner Circle Fringe,” and 156 “Fringe to Plain Inner Circle Fringe” members. When he released (what he described as) the “authorized, reliable, and don’t you know, the correct list” of names four years later for a ball Mrs. Astor hosted in February 1892, the list contained only 319 names of prominent New Yorkers. “Now, that is all, don’t you know,” he added coyly. [“The Only Four Hundred”]

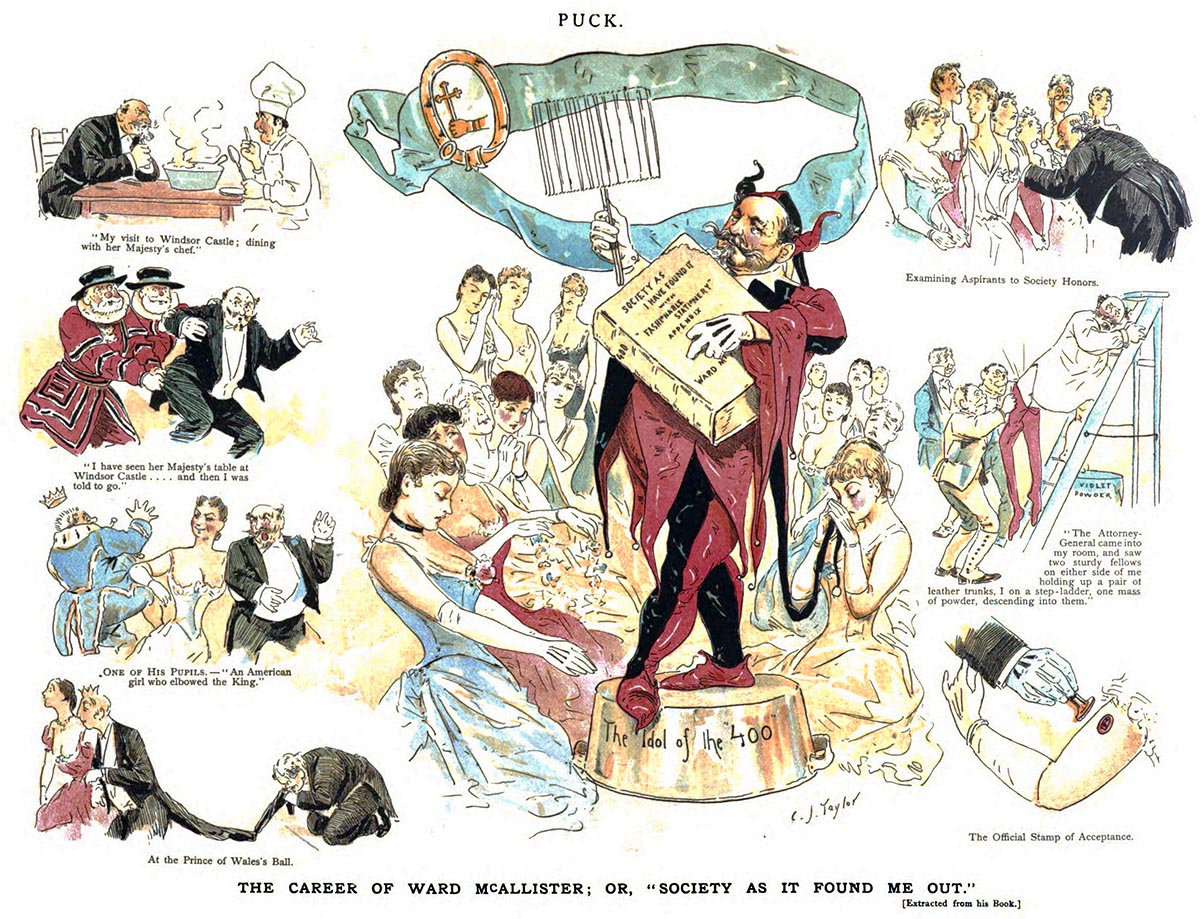

The October 29, 1890, issue of Puck lampooned the author on the back cover with a cartoon titled “The Career of Ward McAllister; Or, ‘Society As It Found Me Out.’” The editors assured their readers that “it is not easy to burlesque him. He is a burlesque himself.”

Society Found and Lost

“If you want to be fashionable, be always in the company of fashionable people.”

—Ward McAllister, in Society As I Have Found It (1890)

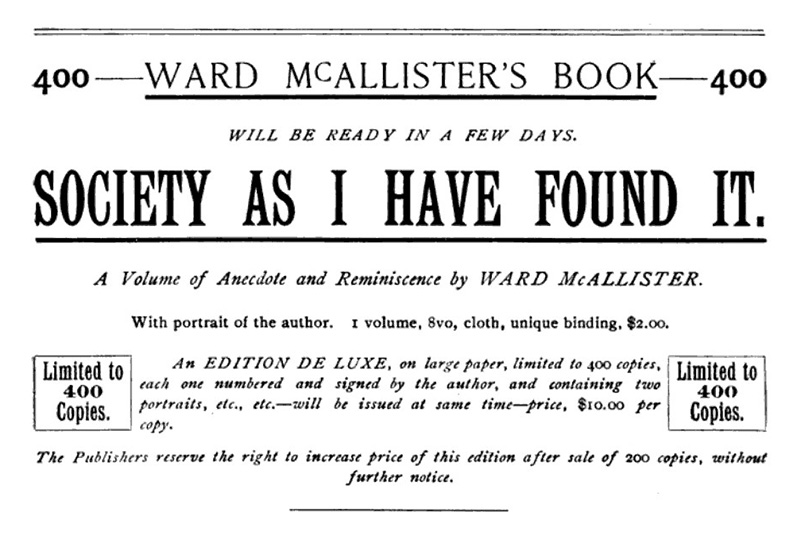

A turning point in McAllister’s career came with the 1890 publication of Society As I Have Found It: The Cuisine, Culture and Fashions of Europe and North America in the 19th Century, by a Man Who Toured the Era’s Fines. This pompous memoir offered reminiscences, epicurean advice on proper entertaining, and maxims for the perfect host. The volume also “forcibly delineated the peculiarities and short-comings” of Gotham’s society set. [“Ward McAllister”] “The sketch must be libel—no society can be as dull as Mr. McAllister would have us believe,” wrote a reviewer for the New York Evening Post. “To assume to describe ‘a Society’ destitute of humor, of wit, of position or distinction, of kindly deeds and generous, unostentatious hospitality is but to make the author and the subject alike ridiculous.” [“The Autocrat …”]

And ridicule it earned. His autobiography spawned a parody titled Society As It Has Found Me Out. A joke in the New York Times offered another twist:

“What do you think, Mrs. Blueblood, of Society As I Have Found It?”

“I think,” with a steely gleam of the aristocratic eye, “that its author will now have to write another book—Society As I Have Lost It. [“What do you think …”]

McAllister came off as conceitful prig leading a vapid and arrogant society. One biographer described the publication as “perhaps the worst decision of McAllister’s career.” [Homberger 216] It earned him “an avalanche of ridicule, scathing criticism, and even abuse” [“Social Mentor Dead”] from the press and from his aristocratic patrons. Society turned against him.

He never wrote another book. “People don’t read books nowadays, don’t you know,” he told the New York Times. “They live too rapidly. They read newspapers.” [“M’Allister is Dead”]

An advertisement for McAllister’s memoir Society As I Have Found It from Publishers’ Weekly Oct. 18, 1890. The publication sank his career as the Dictator of Society.

McAllister’s World

“His delight in life is to entertain; his pride is to entertain well.”

—Kate Field

Through his regular interviews and columns in the pages of Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, McAllister’s strategy evolved into a self-promoting effort to get in print his provocative opinions on a range of etiquette and cultural topics. He relished the publicity. McAllister became famous enough outside of New York to be mentioned frequently in news articles (often as the butt of a joke) across the country with no need for an explanation of his role in Gotham society. One Gilded Age scholar records that “when Ward McAllister was rumored to be aboard a transcontinental train, grizzled cowboys and weather-worn plainsmen galloped miles in the hope of seeing him.” [Churchill 105]

As the Gilded Age began to lose its luster, so did McAllister’s reputation. He was caricatured, lampooned, and insulted by newspapers and cartoonists. His name became a synonym for snobbish, fossilized aristocrats increasingly out of step with the changing times.

He fell victim to infighting within the ranks of the New York aristocracy, and ultimately was cut loose by Mrs. Astor. Bruised from these social battles, he launched one more round of unsolicited advice for ostentatious hospitality, this time aimed at the Windy City as she prepared to host the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

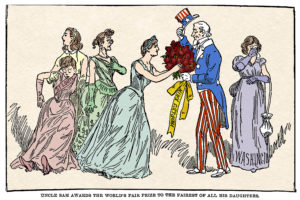

Chicago Wins! “Uncle Sam Awards the World’s Fair to the Fairest of all his Daughters” [Colorized image based on cartoon in the February 25, 1890, Chicago Daily Tribune.]

A Tale of Two Cities

“Unusually affable and polished in his manners, he has the courage of his convictions and is fearlessly outspoken. For this reason, he created a sensation in Chicago, by criticising the manners of its best people.”

—University Magazine, December 1893

After Chicago beat New York in 1890 for the right to host the 1893 World’s Fair, a bitter rivalry between the two cities frequently flared up in the press. Charles Dana served up a scathing roast of Chicago in the pages of his New York Sun in May of 1892. Mr. McAllister’s advice column almost a year later poured combustible spirits—albeit expensive champagne—on the embers of this inter-city spat and started as second great conflagration in the weeks before the Chicago would open her doors to the world.

“Ward McAllister on Chicago,” published in the April 9, 1893, issue of the New York World, served snobby condescension and derision gilded with thin compliments. Small selections of this pre-Fair fracas were included in Emmett Dedmon’s 1953 city history Fabulous Chicago, though his quotes contain several changes from the original publications in the World. In his 2003 best-seller The Devil in the White City, Eric Larson reprinted Dedmon’s (mis)quotes.

We offer in the next installment a reprint of the complete interview “Ward McAllister on Chicago” followed by a series of responses from Chicago and other cities.

Continued in Part 2.

SOURCES

“The Autocrat of the Dining Room” Book News Dec. 1890, pp. 120–23.

Churchill, Allen The Upper Crust: An Informal History of New York’s Highest Society. Prentice-Hall, 1970.

Coates, Foster “Ward M’Allister” Chicago Inter Ocean July 16, 1893, p. 25.

Dedmon, Emmett Fabulous Chicago. Random House, 1953.

Dewey, C. Frank “The Late Ward McAllister” The Sketch Feb. 6, 1895, p. 60.

“From Ward M’Allister’s Eyes” Chicago Inter Ocean Apr. 10, 1893, p. 3.

“The Great Fair” Los Angeles Times Apr. 12, 1893, p. 9.

Homberger, Eric Mrs. Astor’s New York: Money and Social Power in a Gilded Age. Yale University Press, 2002.

“The Late Ward McAllister of New York” The Chautauquan March 1895, p. 737.

“The Only Four Hundred. Ward M’Allister Gives Out the Official List” New York Times, Feb. 16, 1892.

“Major and Minor” Detroit Free Press Apr. 12, 1893, p. 4.

McAllister, Ward Society As I Have Found It. Cassell Pub. Co., 1890.

“M’Allister is Dead” New York Times Feb. 1, 1895, p. 1.

“M’Allister Social Arbiter Died in New York Last Night” Boston Globe Feb. 1, 1895, p. 6.

“Secrets of Ball-Giving” New-York Tribune, Mar. 25, 1888, p. 11.

“Social Salad” Insurance Journal Apr. 1889, p. 148.

“Social Mentor Dead” Chicago Tribune Feb. 1, 1895, p. 1.

Rugoff, Milton America’s Gilded Age: Intimate Portraits for an Era of Extravagance and Change, 1850–1890. Henry Holy and Co., 1989.

“Ward McAllister” University Magazine Dec. 1893, p. 865–66.

“What do you think …” New York Times Oct. 26, 1890, p. 12.

“Who Is Ward McAllister?” Current Opinion June 1889, p. 478.

Leave A Comment