They toppled the Republic at dawn on August 28, 1896.

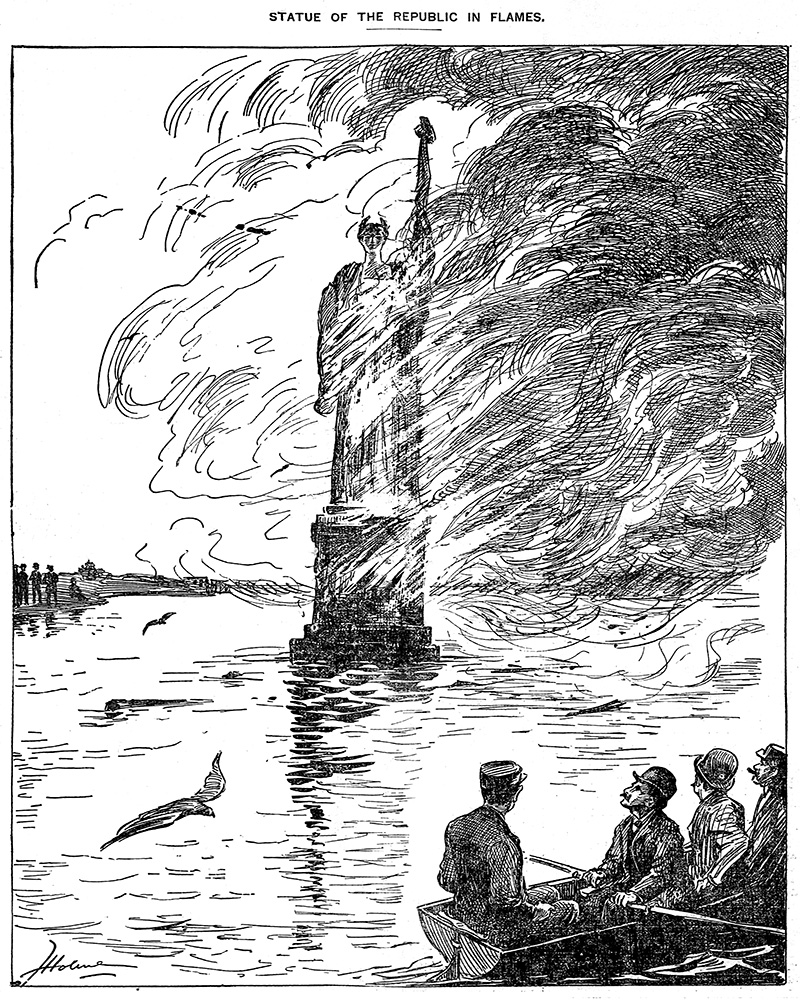

As the first rays of the sun spread across Lake Michigan and into Jackson Park, a funeral pyre lit inside the colossus began to spread up the structure. A flash of light soon appeared in her raised left arm. On a pedestal in the lagoon, the ghostly goddess stood with impassive dignity as muffled cracking within her heralded impending doom. A halo of yellow light formed about her head, and in an instant the laurels encircling her brow burst into a crown of flames.

After this moment of seeming glory, a sizzling tongue shot out from the opening in her right shoulder as her head became wreathed in fire. Flames played about the face of their victim until her cheeks dropped off in lumps.

The blaze crept down her garment, wrapping the magnificent figure in a flaming robe—golden once again. The brilliant conflagration burned with the roar of a tornado, devouring the goddess with malicious eagerness. For twenty minutes she stood defiant in the blazing mantle before finally giving way to the consuming embrace of the flames. Seeming to take one last gasp, the colossus quivered and fell forward into the water. Fire continued to ravage the collapsed heap until almost every vestige of the once-great statue succumbed and sank into a shapeless pile of embers.

It took just thirty-six minutes to cremate the Statue of the Republic.

Her executioners slipped away quietly as crowds arrived on the scene, curious about the smoke rising over the park.

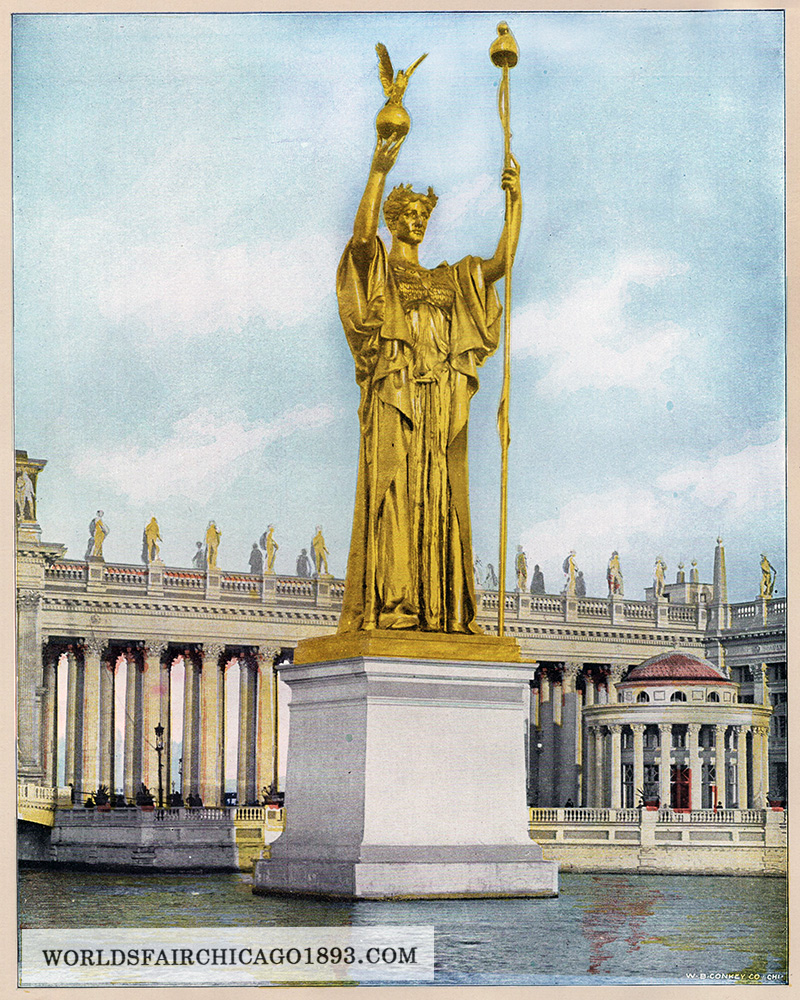

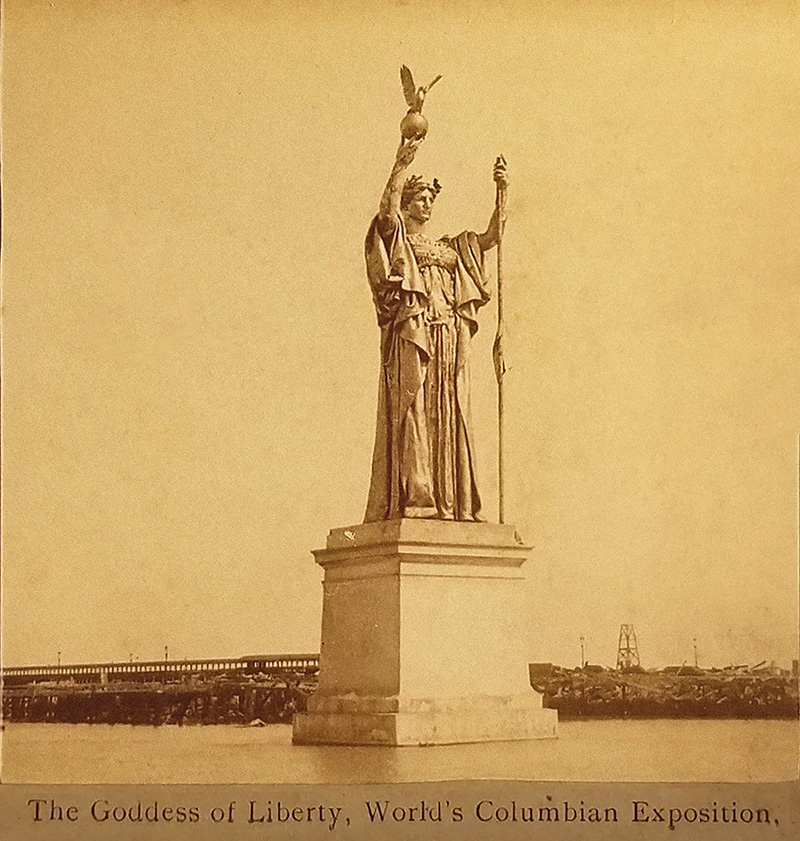

The Statue of the Republic of the 1893 World’s Fair survived three fires (such as this great blaze in January 1894) before being burned down on August 28, 1896. [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894.]

Golden Goddess of the Grand Basin

The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago’s Jackson Park, offered visitors a dazzling array of unforgettable sights. Few received as much attention as the Court of Honor—the stunning “White City” of Beaux Arts exhibit halls and sculpture lining a Grand Basin. On the western side of the basin stood Frederick MacMonnies’ Columbian Fountain with the Administration Building and its golden dome as a backdrop.

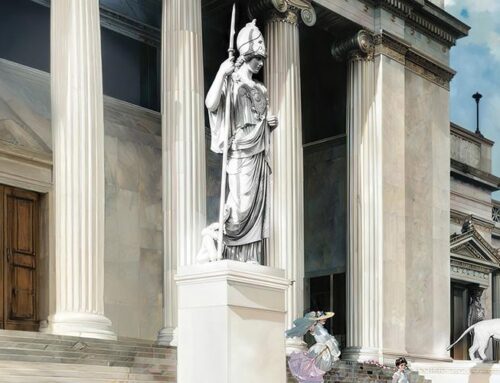

The design of the east end of the basin began at a meeting of World’s Fair architects in Chicago on February 24, 1891. Augustus Saint-Gaudens, whom Daniel Burnham invited to serve as official advisor on sculpture for the Exposition, proposed that the lakeside end of the Court of Honor be architecturally anchored by a portico of thirteen columns (representing the original thirteen states) framing a colossal statue symbolizing the American republic. Charles B. Atwood later developed this design into the Peristyle, with its triumphal arch and colonnade. Saint-Gaudens’ sketch for the statue drew clear inspiration from Frederic Auguste Bartholdi’s colossus Liberty Enlightening the World, installed in New York Harbor just a few years earlier. In July 1891, Saint-Gaudens recommended Daniel Chester French for the job of designing and executing this important statue, which would become an icon of the 1893 World’s Fair.

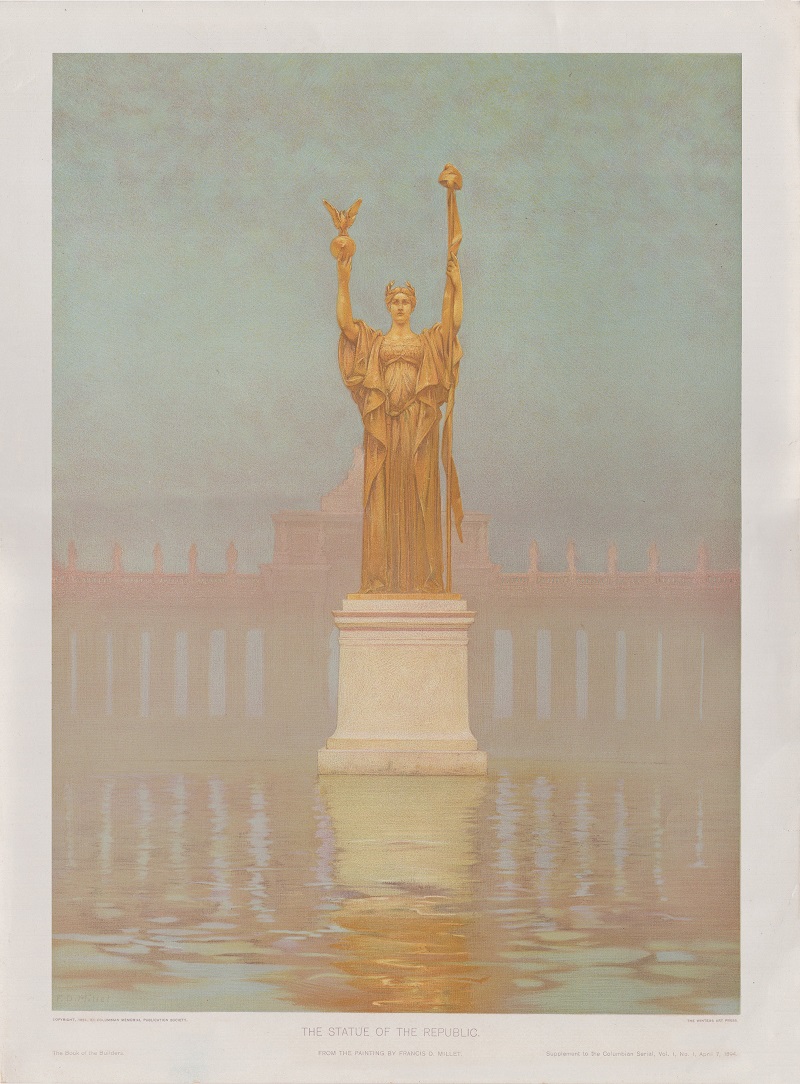

Using French’s thirteen-foot-tall plaster model, workers constructed the sixty-five-foot-tall hollow structure in staff, a stucco-like mixture of plaster and jute fiber, over an iron-and-wood framework. The Republic was the largest statue ever made in America up to that time. The female figure, representing the strength of the American republic and the republican form of government, stood symmetrically wearing a flowing robe having heavy vertical folds and graceful curves. With arms extended above her laurel-wreathed head, she held in her right hand a globe on which an eagle rested with outspread wings. The left hand grasped a pole, on top of which rested a liberty (Phrygian) cap. The entire surface—including the head and arms—was covered in gold leaf.

The gilded goddess of the New World towered over the Court of Honor on a thirty-five-foot base placed in the east end of the Grand Basin. She faced west, toward the Administration Building and the recently-vanished American frontier. A giant canvas cloth covered the figure until Opening Day of the Exposition.

On May 1, 1893, when the President of the United States pushed an electric button to initiate the great transformation scene that officially opened the Fair, a man sitting inside the laurel wreath on the statue’s head performed his appointed task. He cast off the drapery concealing the figure to reveal the Golden Lady in radiant beauty to the hundreds of thousands of spectators stretched around the basin.

Daniel Chester French’s Statue of the Republic became an icon of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894.]

Massive, stately, simple, and severe

“That crowning feature of the Fair,” sculptor Lorado Taft wrote of the Republic, “was more than a big feature; it was a great one.”

In his Columbian Exposition report “The Lady of the Lake”, journalist Julian Hawthorne praised French’s celestial statue:

“It is a work on which any artist might be content to rest his reputation. It is massive, stately, simple, and severe. The heavy robe falls in straight folds, like those of the early Greek statues. The pose is at once the simplest possible, and the most impressive. So should stand the human symbol of the mightiest of nations. It is as dignified as a tower, and as splendid as a goddess.”

For six months, the Republic colossus stood witness to the great Exposition. She saw parades of dignitaries including President Grover Cleveland and Princess Eulalia of Spain, the first rotation of the sky-scraping Ferris Wheel on the distant horizon, Saint-Gaudens’ own gilded goddess Diana twirling in the wind atop the adjacent Agricultural Building, spectacular nightly illuminations of the Court of Honor and firework displays, the horrific Cold Storage Building fire that took fifteen (or sixteen?) lives, lovers enjoying romantic gondola rides through the lagoon, the largest peaceful gathering of people up to that point in human history for the Chicago Day celebration, and the somber memorial for a slain mayor on what should have been a festive Closing Day on October 30, 1893.

Work to dismantle the Exposition began immediately. The Golden Lady watched as exhibitors packed up their displays and crews disassembled buildings for scrap materials or, in a few cases, for reconstruction elsewhere. The terms for using Jackson Park for the World’s Fair included the stipulation that the World’s Columbian Exposition directors must return the site to Chicago’s South Park Commission in essentially the same condition as it was when turned over to them in 1891. Restoring the fairgrounds back to a city park would take years, and all the while Chicagoans debated how the Fair’s buildings and statuary and legacy might be preserved.

Terrible and unexpected forces would have the final say.

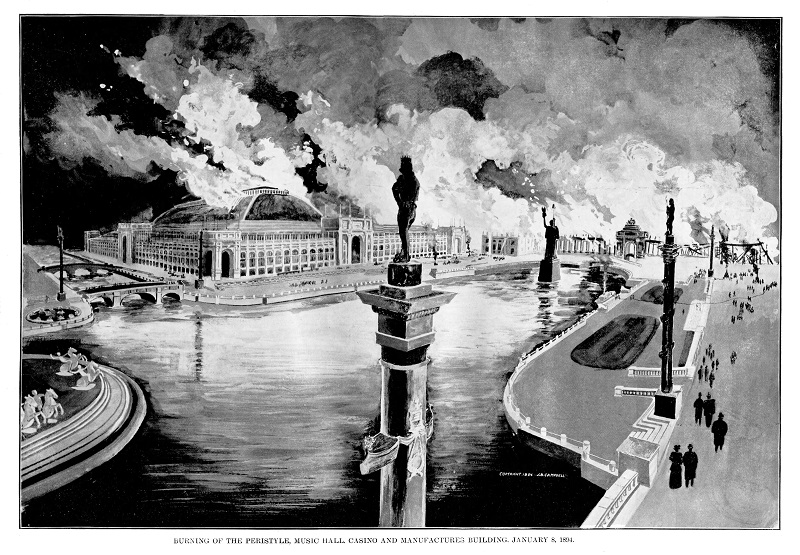

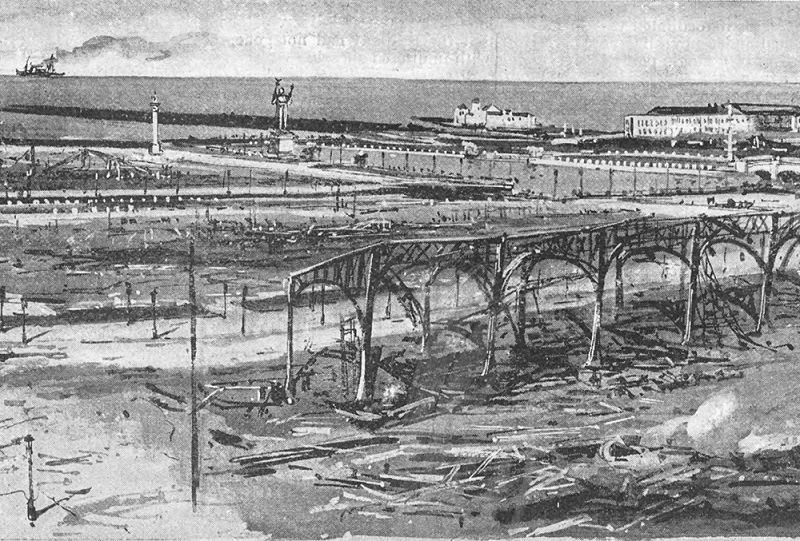

Burning of the Peristyle, Music Hall, Casino and Manufactures Building on January 8, 1894. [Image from Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume II. M. Juul & Co., 1894.]

Pathetic in its grandeur

Three times disastrous fires raged around her, and three times she survived.

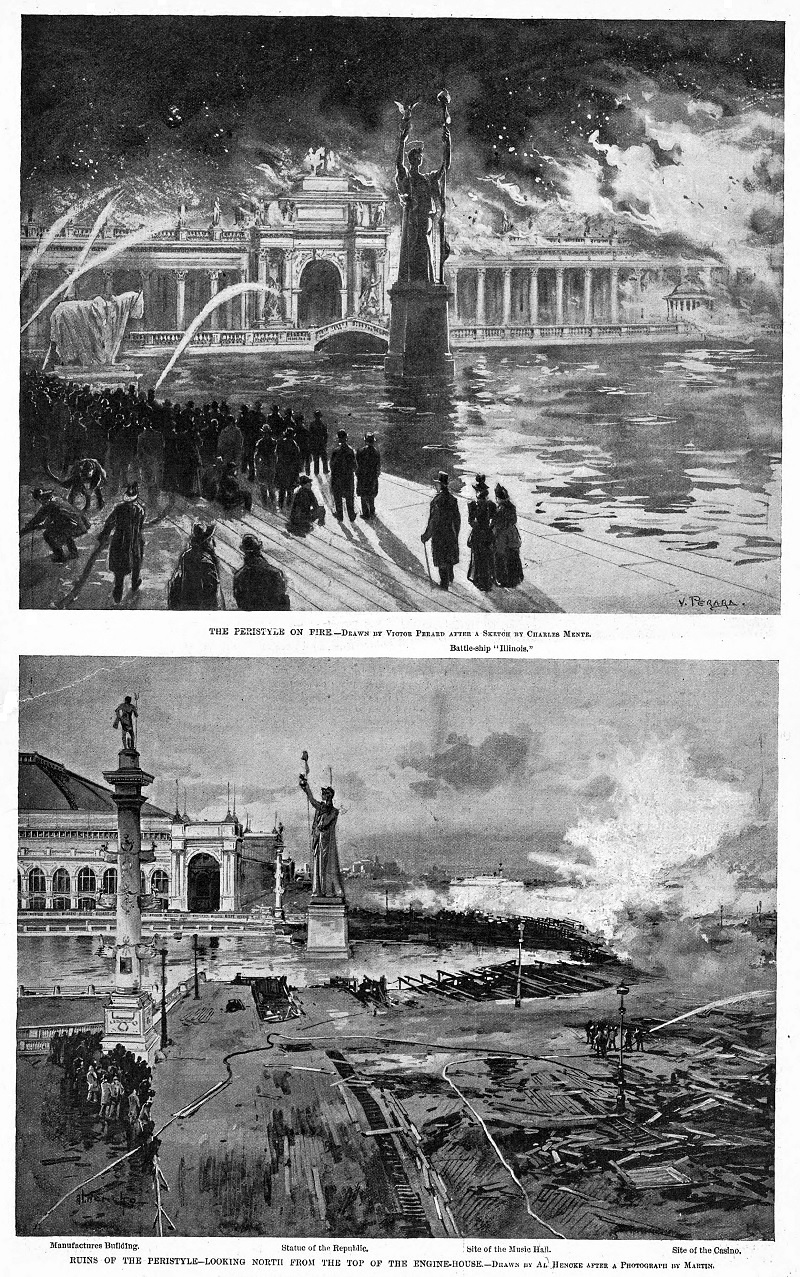

On January 8, 1894, the first great post-Fair fire consumed much of the east end of the Court of Honor. French’s Statue of the Republic stood “in the midst of it all like a gigantic silhouette, with uplifted arms as if appealing for help,” wrote the Chicago Tribune (Jan. 9, 1894). She held her liberty cap defiantly among clouds of black smoke as fierce flames danced around her for more than an hour. While the heat from this “Peristyle Fire” was intense enough to melt the ice on the Grand Basin, it barely tarnished the golden statue. By morning, the conflagration had completely destroyed the Peristyle, Casino, and Music Hall and damaged parts of the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. Had the firemen not saved it from the flames, the Republic likely would have burned down that night, too. The next morning, the majestic golden goddess of the Fair looked as brilliant as ever, “except for a blistered right arm and a black spot over her heart,” noted the Chicago Herald.

Drawing by Victor Perald of (top) “The Peristyle on fire” and (bottom) “Peristyle looking north from the top of the engine-house” showing the events and aftermath of the January 8, 1894, Peristyle Fire. [Image from Harper’s Weekly Jan. 20, 1894.]

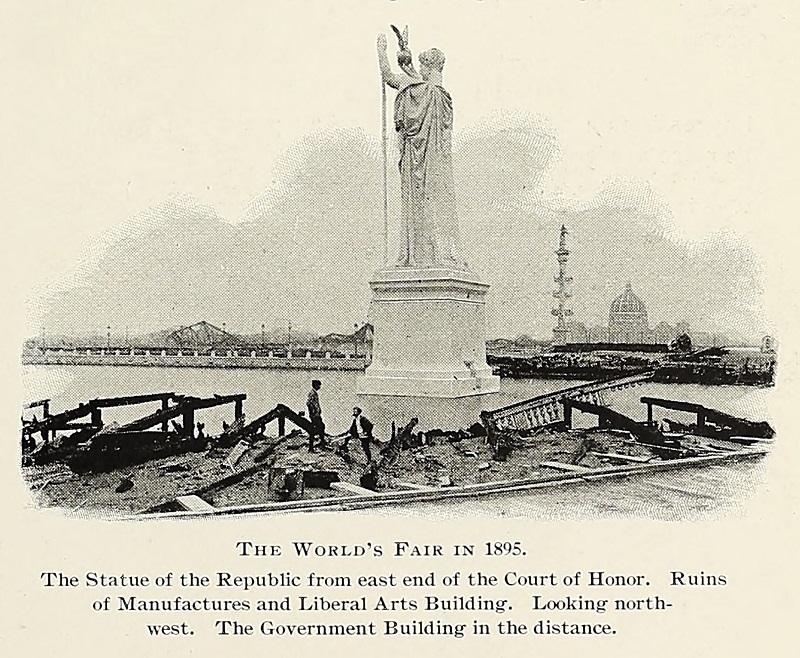

A gleam of gold in a desolate landscape, the Statue of the Republic stood alone in the Court of Honor. The “leveling of all the palaces has left [it] in magnificent exposure,” observed the Tribune (July 15, 1894). Describing the statue as “pathetic in its grandeur,” the Chicago Inter Ocean also recognized that, with the surrounding buildings of the White City gone, the Republic now stood to better advantage:

“Particularly was this so when last winter the golden figure towered above an unbroken field of snow. On the night of the last fire the flames seemed to separate and pass by on either side, and when the sun rose the next morning there seemed nothing left untouched but the golden woman of the lagoon.”

“With only the sky for a background,” observed the Washington (DC) Evening Star, the statue “shows it proportions and lines to better effect now than before.”

The World’s Fair grounds after the great fire of July 5th, 1894. The Statue of the Republic and one rostral column are that is left standing in the former Court of Honor. [Image from Harper’s Weekly June 21, 1894.]

Our Golden Girl stands shining in the sun!

This tribute to the survivor of three fires appeared in the Chicago Tribune on July 30, 1894:

Westward she looks; around her lies

A desolated scene,

Where mid a summer’s palaces

She held her court as queen.

Behind her mourns the inland sea;

Before her stretches far

Her prairie—empire of the West

Beyond the horizon’s bar,

Not all alone, for Egypt lifts

Her obelisk in sight;

Rome’s pillar of the fretted prows

Stands close upon her right.

Ghosts of the ages that are gone,

Prophets of days to be,

Proclaim in wisdom and in might

That Love is Liberty,

Republic hail! Though beauty dies,

The peoples shall be one.

Rejoice O World, our Golden Girl

Stands shining in the sun!

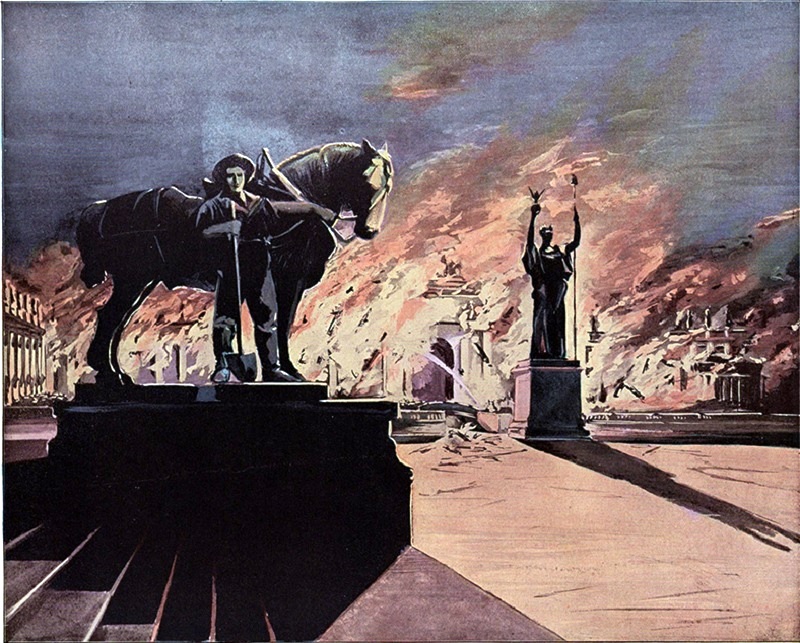

The Statue of the Republic inspecting the scene of desolation after the Peristyle fire of January 8, 1894. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

Incapable of obliterating the glories

What Fire started, the cruel hand of Time continued. Blazing brands falling onto the structure during the 1894 fires had left holes. Rain and snow found lodgment, working ruin that flames could not accomplish. Decay set in. The figure became dingy, and staff crumbled off her day after day.

The Inter Ocean offered this somber portrait in August 1894:

“The Goddess of the Republic in the grand basin at Jackson Park looks around upon such a scene of ruin and desolation that it requires but little use of imaginative faculties to discern a motive, or cause, for the lugubrious aspect of her large and generous physiognomy. Her own erstwhile brilliant garments of gold present such a dilapidated appearance that the severity of the gloom pervading her brow is visibly tinged with disgust. She looks as if the richness of her attire had attracted predatory incursions upon the sanctity of her slumbers, the left arm being almost entirely stripped of gold, and other portions of her royal robe showing patches of white several yards in extent. There is, however, an unfathomable pathos in the dignity with which she stands guard over the scenes of almost indescribable ruin …. She realizes that the elements themselves are incapable of obliterating the glories of the grandest results of human endeavor, which will live in song and story and pictures for centuries to come.”

Two views of the former fairgrounds in 1895 from east end of Court of Honor: (top) looking west and (bottom) looking northwest. Note that the Statue of the Republic has been painted white and is missing the Phrygian cap atop the staff in her left hand (see below). [Images from the Inland Printer, May 1895.]

A visitor to Jackson Park on the one-year anniversary of the closing of the Fair noted that the giant white statue “became more beautiful and imposing than before.” The Tribune wrote that “seen in the moonlight, the figure has a ghostly aspect,” while another reporter described her standing “in majestic whiteness, like some great, ghostly sentinel.” For how much longer would she haunt the former Dream City?

A ghostly image of the Statue of the Republic on the eastern horizon, detail from a photograph taken by J. C. Olmsted (of Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot) on October 24, 1895. [Image courtesy of the United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.]

Olmstedizing and beautifying Jackson Park

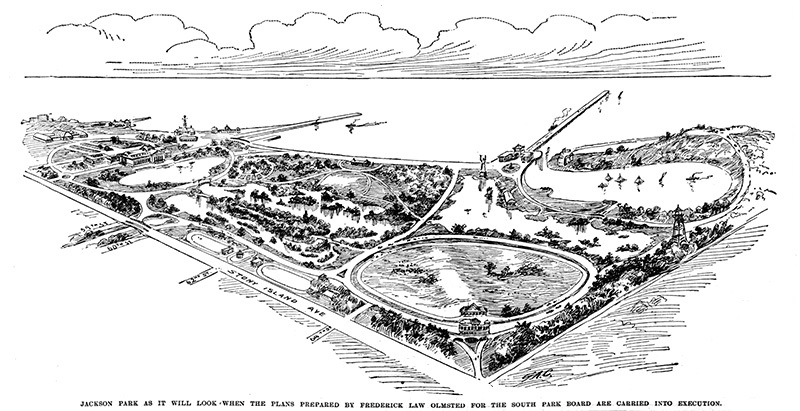

An 1895 plan to renovate Jackson Park, using income collected from salvaging materials from the remaining Exposition buildings, would create a 560-acre “park for the people” along the shore of Lake Michigan. “Incidentally,” noted the Tribune, “it will be at the same time a cemetery to one of the world’s greatest achievements.” The park renovation plan meant that all but a few “architectural beauties” from the Exposition would be “wiped from the face of the earth.” Would the Statue of the Republic be among them?

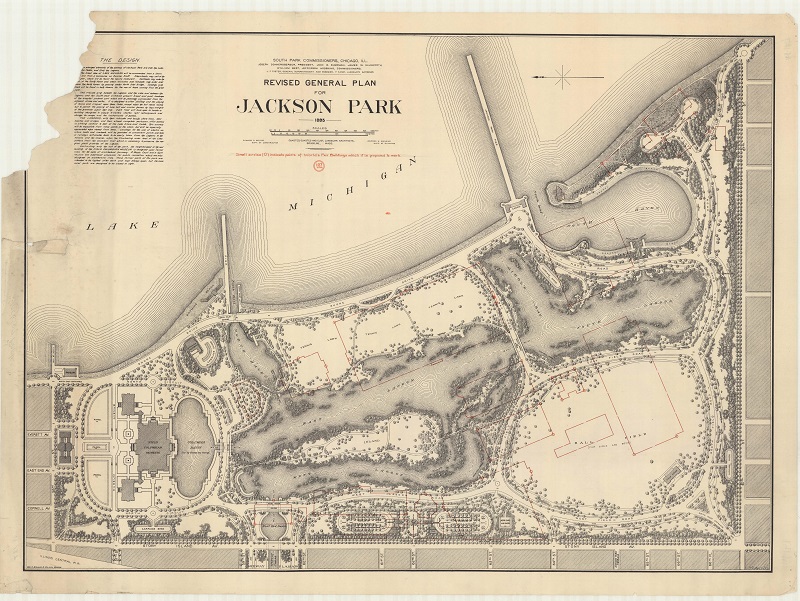

The park redesign by the firm of Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot included a new esplanade running along the lakeshore from the north and then turning west across the park (essentially the location of the current Hayes Drive). A birds-eye view of the proposed improvements published in the Tribune shows the Statue of the Republic remaining in its original location, even as the surrounding Grand Basin and South Lagoon waterways would be reconfigured.

A plan to improve Jackson Park shows the Statue of the Republic remaining in its original location. [Image from Chicago Tribune May 23, 1895.]

As remaining demolition work wrapped up in 1896, the Tribune noted that “the work of Olmstedizing and beautifying Jackson Park” could commence.

A map showing the Revised General Plan for Jackson Park by Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot. This version, from October 5, 1896, includes outlines of the former 1893 World’s Fair Buildings (shown as red lines) with locations for proposed commemorative building markers (shown as small red circles). Notably, this and earlier versions of the map dated 1895 and May 11, 1896, do not show the Statue of the Republic, though it then stood in what is here called “Middle Bay.” [Image courtesy of the United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.]

The Republic stands among the ruins of the former Court of Honor in 1894. [Image from Chicago History Museum (ICHi-25231).]

The mutilated but sturdy goddess stood defiant

Ultimately, the Statue of the Republic did not perish through carelessness, malice, or accident, but by design.

As the South Park Commission took control over renovation work in Jackson Park in May 1896, the condition of the Republic continued to deteriorate. At some point the previous year, the Phrygian cap atop the right-hand staff was lost. In mid-August 1896, the right arm that held aloft the globe and eagle weakened and fell. [These relics managed to be saved and transported to Ohio where they survived for many years!] And yet, the mutilated but sturdy goddess stood defiant. The Chicago Daily News described the once-majestic figure as “a dilapidated ruin, a sorrowful wreck, cracked and shattered.”

The Statue of the Republic (“Goddess of Liberty”) stood defiant, even after losing her Phrygian cap. [Image from an Underwood & Underwood stereoview card.]

The Chicago Record reported that “several plans were offered by which the statue might be preserved, but none met with the approval of the majority.” Park commissioners felt that they could not justify spending any more public money on a one-armed, white-washed colossus. Faced with the contrast between “her unsightly appearance of decayed respectability” and the beautification of her surroundings in Jackson Park, the Commission issued a death warrant.

When taking this decisive action at their meeting on August 12, the South Park board chose to keep the execution a secret. They delegated the task of destroying the statue to mechanical engineer and Assistant Park Superintendent A. H. Wilder, who chose fire as his tool. The Commission deemed burning the statue at night too hazardous because it would attract too many people, and a proposal for a public ceremony and celebration also was dismissed. They thought it best to raze the Republic—in secret—at daybreak.

On Thursday, August 27, Captain Kelly of the South Park Police placed the orders to burn the Republic the next morning, and Capt. Shippy of the Woodlawn police notified the fire companies in the district that a blaze would be set in Jackson Park at dawn.

The secret cremation of the Statue of the Republic on the morning of August 28, 1896. The newspaper artist mistakenly drew the already-missing Phrygian cap. [Image from the Chicago Chronicle Aug. 29, 1896.]

“Let ’er go!”

At 5 AM on Friday, August 28, 1896, Mr. Wilder and a few assistants met in Jackson Park. They loaded wood, kerosene, and torches into a scow, and rowed over to the statue.

Into several large holes bored in the base of the structure, they filled shavings saturated in kerosene. Entering the statue through the rear door in its pedestal, more wood was laid carefully about the interior of the largely hollow structure. When a hatchway in the crown of the head (accessed by climbing an internal stairway) and the bottom door both were opened, the 100-foot structure would act as a chimney.

With no ceremony in the affair, Mr. Wilder stepped forward with a flaming torch and lit the piles of kindling at the base, calling out “Let ’er go!” to initiate the burn. Kerosene dripping from the skirt of the World’s Fair martyr blazed up angrily. Wilder and his team quickly jumped back into the scow and returned to the shore of the basin, where they joined a park policeman and a few other witnesses.

“It remained for fire to consume her,” observed the Tribune, “as all such Titanic creatures ought to be consumed.”

“Floating slowly upward, growing fainter and fainter as it ascended, spread, and finally dissipated in the still air, a column of bluish smoke was visible at Jackson Park this morning against the clear sky,” reported the Chicago Journal. “It came from the funeral pyre of the Republic, the presiding goddess of the great Columbian Exposition.”

This rising column of smoke drew many curious neighbors into Jackson Park to witness the fiery scene of destruction. Crowds gathered all morning to see the ruins of the Republic. Even after the fire eventually subsided, ashes continued to drift in the errant lake breeze.

Francis D. Millet’s painting The Statue of the Republic. [Image from Burnham, Daniel Hudson. The Book of the Builders. Columbian Memorial Publication Society, Chicago, 1894.]

The ghost of the fairy scene

Only a smoldering heap of cinders and a pleasant memory marked the spot where the proud, but dilapidated, Statue of the Republic vaporized on the morning of August 28, 1896. (In an interesting coincidence, Frederick Law Olmsted left this world on the same day, exactly seven years later.) The spot where she had stood for more than three years is now underneath Lake Shore Drive, close to where it crosses over Hayes Drive.

This grand icon of the Columbian Exposition survived long after the surrounding Dream City had vanished. “If there be any truth in sentiment,” commented the Tribune (Aug. 29, 1896), “the spiritualized goddess has not deserted her place of habitation, but still abides there in ward of the ghost of the fairy scene of which she was for a brief but never-to-be-forgotten time the presiding genius.”

SOURCES

“At the Institute” Chicago Inter Ocean July 22, 1894, p. 27.

“Big Statue to Be Burned” Chicago Chronicle Aug. 28, 1896, p. 1.

“Bits of City Life” Chicago Tribune Dec. 30, 1894, p. 30.

“Dismantled White City” Washington (DC) Evening Star Dec. 14, 1895, p. 18.

“Fair is Fire Swept” Chicago Tribune Jan. 9, 1894, p. 1.

“Gone to Four Winds” Chicago Tribune May 22, 1896, p. 1.

“Great Even in its Ruins” Chicago Chronicle Oct. 27, 1895, p. 14.

Hawthorne, Julian “The Lady of the Lake. At the Fair.” Lippincott’s Magazine August 1893, pp. 240-47.

“Her Funeral Pyre” Chicago Journal Aug. 28, 1896, p. 5.

“Its Glory in Ashes” Chicago Tribune Jan. 10, 1894, p. 1.

“Last of the Republic” Chicago Record Aug. 28, 1896, p. 1.

“Loss Will Be Small” Chicago Herald Jan. 10, 1894, p.1-2.

“Money for a Park” Chicago Tribune May 23, 1895, p. 1.

“Proud Statue in Ashes” Chicago Daily News Aug. 28, 1896, p. 1.

“Reconstruction of Jackson Park” Chicago Tribune Oct. 6, 1895, p. 49.

“Republic Is No More” Chicago Evening Post Aug. 28, 1896, p. 1.

“Saunterings” DeKalb (IL) Daily Chronicle July 20, 1895 p. 2.

“Statue of the Republic” Chicago Tribune July 30, 1894, p. 3.

“Statue of the Republic Burned” Chicago Inter Ocean Aug. 29, 1896, p. 7.

“Statue of the Republic is Burned” Chicago Tribune Aug. 29, 1896, p. 5.

Taft, Lorado The History of American Sculpture. MacMillan Co., 1924, p. 322.

“White City Revisited” Chicago Tribune July 15, 1894, p. 29.

“World’s Fair Ruins” Chicago Inter Ocean Aug. 20, 1894, p. 7.

Leave A Comment