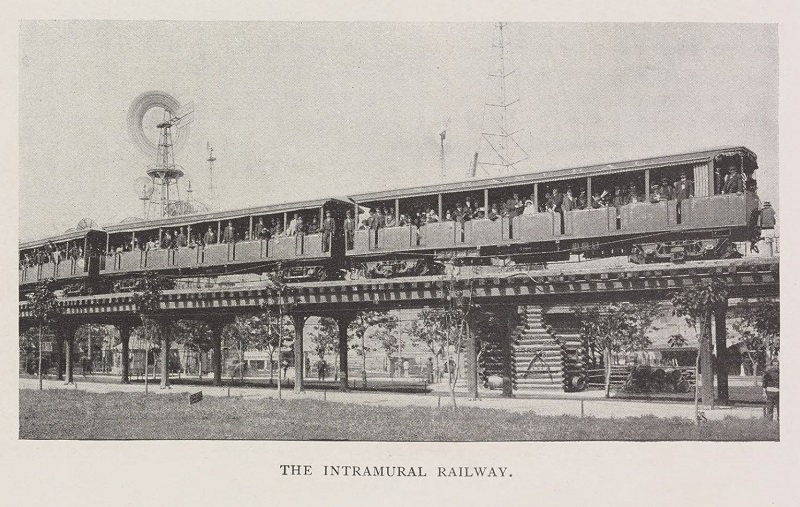

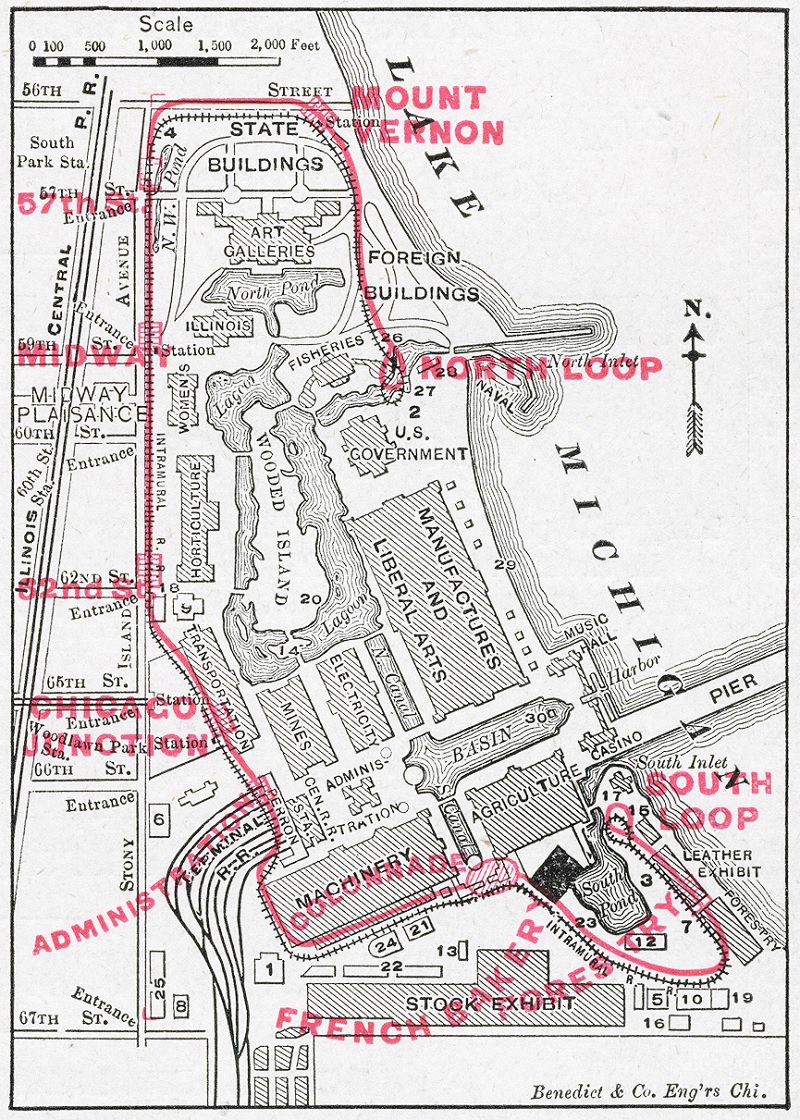

One challenge for the designers of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition was finding ways to transport visitors around the enormous fairgrounds. Walking the main grounds—almost a mile and a half from north to south and three-quarters of a mile wide across the south end, and a mile-long Midway Plaisance—exhausted many fairgoers. Rolling chairs offered a personal mode of transportation around the grounds, while watercraft such as electric launches and Venetian gondolas provided scenic routes through the waterways. The fastest means of getting around Jackson Park, though, was by riding a train through the air.

The Intramural Railway, with trains filled with riders, passes through the southeast end of the grounds at the 1893 World’s Fair. [Image from The Graphic History of the Fair. Graphic Co., 1894.]

A map showing the route and stations of the Intramural Railway at the World’s Columbian Exposition. [Image from Wikipedia.]

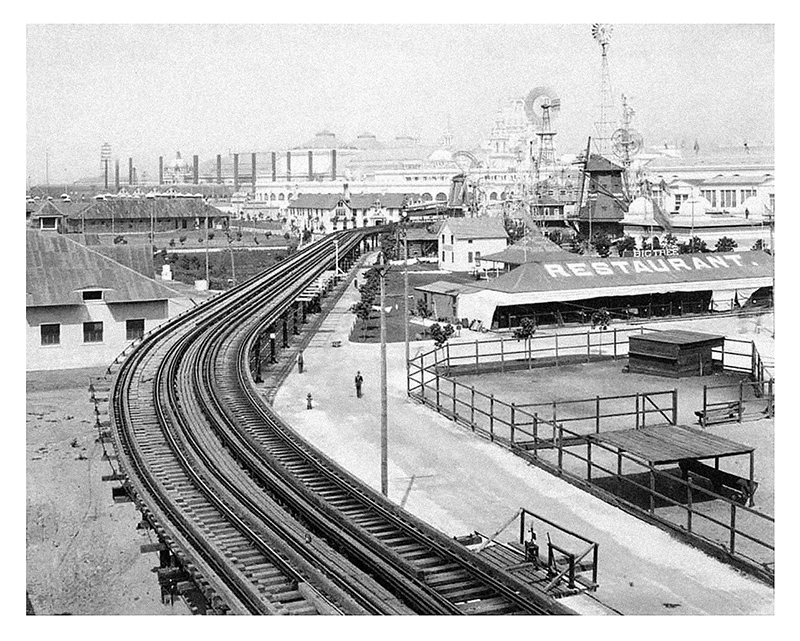

Another view of the southeast fairgrounds of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition from the Intramural Railway. [Image from the Ryerson and Burnham Archives of the School, of the Art Institute of Chicago.]

From Electricity at the Columbian Exposition (R. R. Donnelley & Son’s Co., 1894) by John P. Barrett. Barrett served as the Chief of the Department of Electricity for the Columbian Exposition.

With twelve trains in operation, making a total of 196 round trips daily, there were no delays or accidents, aside from a few of an unimportant nature and such as were liable to happen on any railroad. There was but one personal injury of a serious nature, and that was due to the carelessness of the injured party and his neglect to heed the repeated warnings given by both passengers and employees.

The management of the road regarded this record with a great deal of pride and satisfaction, for when it is considered that the crowds that patronized the road were constantly changing from day to day, and that a very small percentage had any knowledge of their surroundings and were entirely unaccustomed to this mode of travel, had no idea of where they wanted to go, or how to reach any given point in the Fair grounds, it was to be expected that in their confusion and excitement someone would be injured almost daily. There were many who did not realize that there was any more danger in trying to get on or off a train that was moving than would be the case with a horse car, and it required constant care and watchfulness to prevent numerous accidents from this cause.

The inexperience of visitors from the rural districts was a constant menace to their safety as well as a strain on the energies of the officials of the road. This was particularly the case during the last three months of the Exposition, when both trains and platforms were crowded.

When the road first opened the fare charged was ten cents to ride from one loop to the other, or from any intermediate station to either loop. This was frequently considered an excessive amount and many passengers who took trains at intermediate stations expressed dissatisfaction more or less forcibly at being obliged to leave their trains at the end of the road to buy tickets for a return trip. To meet this objection collectors were placed at the terminal stations to collect fares from those who wished to remain on their trains. This arrangement was satisfactory to a certain extent, but there were many who objected to paying additional fare to return, the majority not being satisfied unless they could make a round trip and get off at the station at which they got on.

While it was the object of the management to make the road popular, yet there was no way by which passengers could be restricted to one trip, and it was necessary to either collect fares from all passengers at a given point, or remove the restriction entirely and allow them to ride as long as it suited them. Realizing the difficulty of receding from the latter plan should it once be adopted, there was great hesitation about giving it a trial.

The fact, however, that trains were not filled, and the desire to attract business, finally decided the matter, the collectors were taken off and passengers remained on the trains as long as they wished to. There were some who rode for hours, looking anxiously for the end of the road, and were not conscious of the fact that they were going over the same ground many times, even after they had counted four or five Ferris Wheels.

Leave A Comment