June 8, 1893 was “Princess Eulalia Day” at the World’s Columbian Exposition. Attendance swelled to around 169,000 visitors—the largest yet. Most were eager to catch a glimpse the Infanta from Spain as she toured the fairgrounds. A report from that day reprinted below (originally published in the July 12, 1893, issue of Garden and Forest) makes only a passing mention of the royal guest. Instead, the author focuses on the natural and man-made beauty of the 1893 World’s Fair, while dreaming of Xanadu and Arcadia. [Section headers have been added to the original publication.]

A Glorified Park

by M. C. Robbins

Jackson Park will live in the memory of those who have had the good fortune to see the World’s Fair, as a creation as enchanting as the vision in Coleridge’s broken dream. That all this magical splendor should have been evolved from a swamp with sparsely wooded shores proves that America possesses at least one pre-eminent creative imagination, while the sorrowful knowledge that this realization of an artist’s dream is not a permanent possession, but simply food for memory, adds intensity to the impression and stimulates the mind to grasp such general effects as will not fade from the recollection.

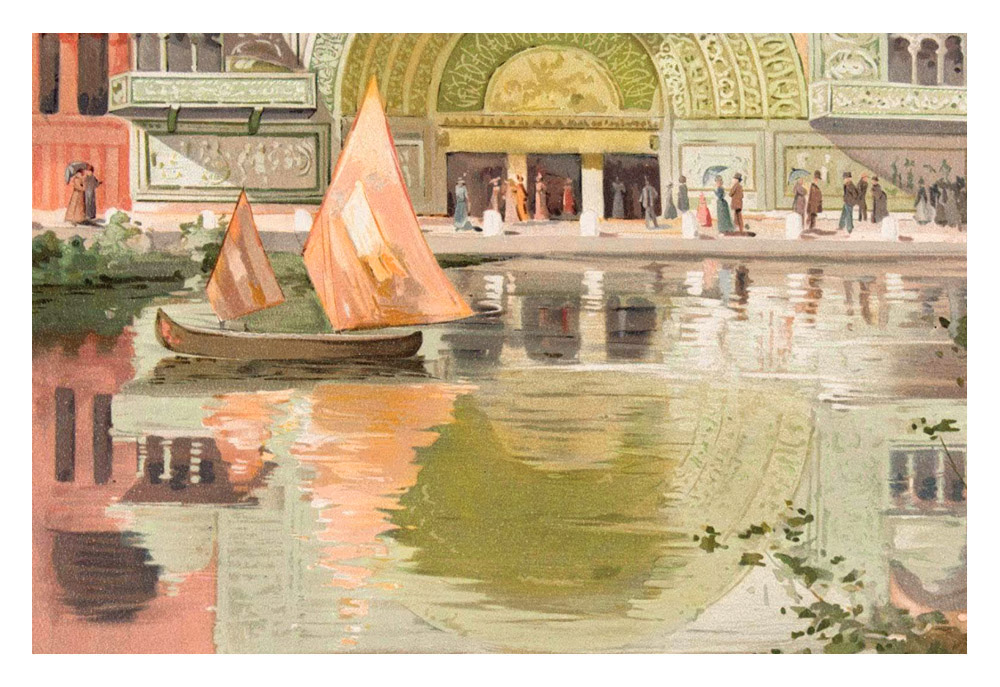

“A Water Reflection, Transportation Building” by Louis Meynelle. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

A central idea of imposing beauty

It is a mistake, therefore, in a week’s visit, which is all that is allowed to most of us, to attempt too much detail; for this is really to waste one’s opportunity. The outdoor charm of moving life, of glittering water, of stately architecture, of pleasant gardens, is what one should seek to seize and hold as an enduring memory, and it is this which is to produce upon our people the most important effect. To the active and eager minds of the great west this revelation of beauty means a bound from the real to the ideal, and no one can estimate the results which may come to the country in its artistic development through the influence which such a scene must exercise upon young and impressible natures, with the limitless resources of America behind them. The tremendous effect of the Columbian Exposition is produced, after all, by the sense of native wealth and strength and boundless power in all directions which it reveals.

First and last, and all the time, there is present in our minds a certain passionate joy that in these United States such a thing is possible, and that out of the strong has come forth such sweetness. That our material resources are immense we knew, but here they are marshaled in a way which none deemed possible, and subordinated to a central idea of imposing beauty. There are details which are not artistically perfect, but he who would cavil at blemishes in such a panorama must be querulous indeed.

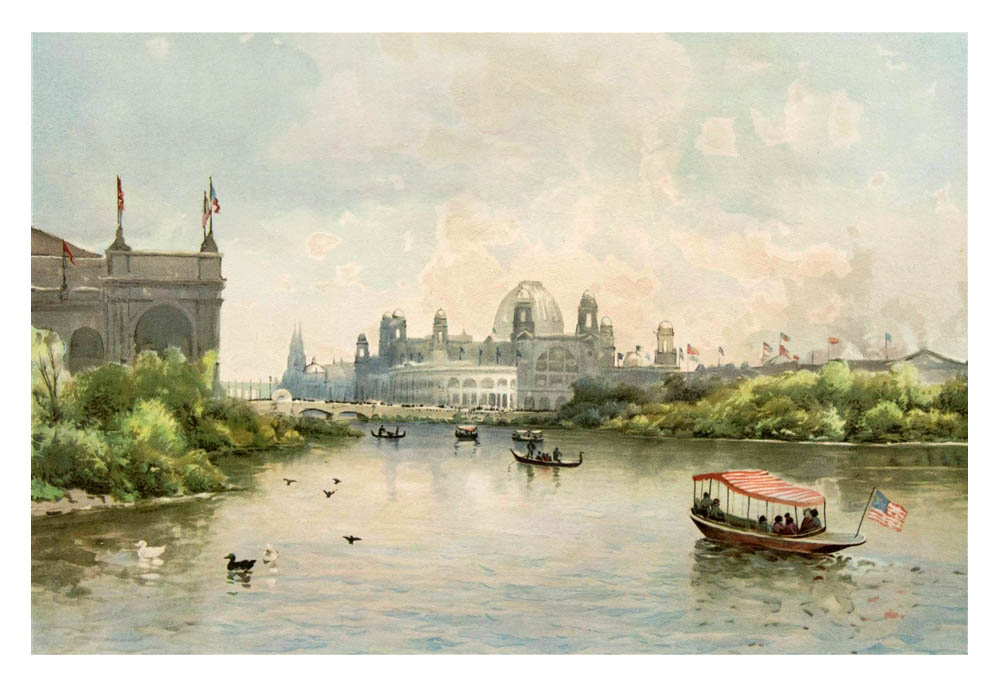

“The East Lagoon” by C. H. Eaton. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

A fitting introduction to the Fair

Though our lodging was hard by the gates of the Fair, a wise friend bade us approach it first by water, for the sake of the general effect, so turning our backs upon the shining domes we whirled to the Van Buren Street pier and embarked upon a little steamer which was to take us in forty minutes down Lake Michigan to the White City. As we put off upon the dancing waters, the color of which is superb—a splendid green mottled with purple, like the Mediterranean Sea—the long stretch of the city of Chicago formed an imposing picture. Beautiful in the haze which softened their stiff outlines, the tall, twenty-storied buildings rose like towers. For fifteen miles along the lake stretch the buildings of this magical town, which fifty years ago was but a house in a swamp. This is the way to gain an idea of the extent and importance of the Lake City, and it is a fitting introduction to the Fair, whose roots it feeds with wealth and enterprise and generosity.

One who sees that city on its great, fresh, inland sea, has an assured conviction that no eastern town could have afforded such an opportunity for the Exposition, and that here in the heart of our country, easily accessible to the boundless west, which most needs its lessons, should this Fair have been held.

As the spires of Chicago grow small in the distance the White City’s outlines become more distinct, and the level line of the Peristyle, backed by domes and towers, concentrates our attention. Very impressive is this array of buildings and columns from the lake, and the moment of our approach is full of excitement. Here is the true entrance-gate. The long line of columns surmounted by plumed Indian figures, alternating with graceful maidens, is imposing, and everything prepares for the coming effect. It is a great moment.

“The MacMonnies Fountain by Night” by Jules Guerin. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

Here the New World has achieved classical beauty

The mind and heart swell with patriotic pride as might have done those of a Roman at the sight of the Forum, of an Athenian when he climbed the steps of the Acropolis. It is our people who have done this, and we, too, have a right to artistic glory, for here the New World has achieved classical beauty.

The site of this water court, with the buildings on either hand, the broad steps leading down into the canal, the dome of the Administration Building at the further end, the flitting launches and gondolas, the moving crowd along the stately piers, the imposing groups of statuary on its borders, the tall columns with their sculptured trophies of adornment, the beautiful fountain, with its horses rising from the waves, all veiled in silvery water, is a vision never to be forgotten, and one of satisfying beauty.

Entering one of the little boats propelled by electricity, we silently and swiftly made the tour of the whole wonderful region, stopping at the great white flights of steps that lead up to each palace, learning their names, wondering at their proportions, rejoicing in the harmonious colorings of their flags which flutter from myriads of staffs. You may think you know it all beforehand, you have read of it a hundred times, but the enjoyment is novel and intense, and more than ever does enchantment take possession of you. As days go by, and you grow familiar with the scene, its splendor enhances rather than palls, familiarity increases the charm, as it does with all truly beautiful things.

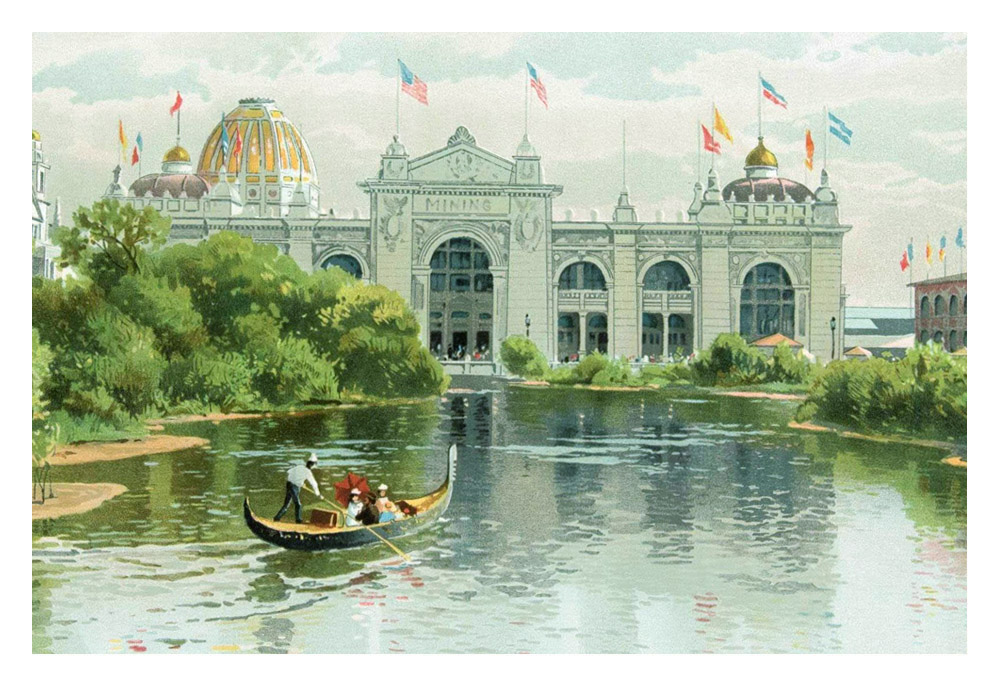

“The Hall of Mines from the West Lagoon” by J. D. Woodward. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

The most beautiful view of the whole Fair

The place to stand at sunset is on a bridge that leads from the Wooded Island to the Fisheries Building, where, it seems to me, the most beautiful view of the whole Fair is to be had. The longest stretch of the canal lies before the eye. On the left the imposing mass of the Liberal Arts Building makes a fine perspective; on the right the flowering shrubs and green trees of the island form an agreeable mass of color, behind which rise distant domes and towers. The length of the canal is broken by bridges that give a Venetian effect to the vista, and in the background, far away, is seen the obelisk, backed by a colonnade which forms a fitting finish to the picture, recalling the beautiful canvases of Claude and Canaletto.

The yellow light plays softly on the white buildings, under the bridges glide the graceful gondolas, distant bells are softly chiming, flowers are blooming, the summer throng comes and goes, idly lingering to gaze. All light, color, perfume, melody, the realization of the most fanciful dream of those old masters. The sense of beauty is so intense, so gratifying that the eyes fill with tears, and for a moment the work-a-day world vanishes, and we, too, are in Arcadia. And this enchanted scene seems to belong not to the America of to-day, but to some far-off hour to come in its millennium.

“Sunset on the Dream City” by H. D. Nichols. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

A memory to broaden the horizon of life forever

If all this seems fanciful, it is but the natural outcome of a scene which of itself is dream-like, and this great sensitive crowd, learned and humble, ignorant and aspiring, drinks in all this vision, and comes out from it enlarged, uplifted, with new knowledge and new aims, and with a memory to broaden the horizon of life forever.

The first night of our arrival was that of the Infanta’s visit, and fireworks and illuminations drew a vast throng of spectators to the grounds. Though the whole fair is well lighted, the illuminations are all confined to the Court of Honor and its adjoining buildings, which are outlined in fire—the dome of the Administration Building being furthermore surmounted with a row of torch-like lights which alternate with the electric lamps.

Near the surface of the water runs a line of incandescent lamps, which gleam and are reflected like jewels, and every now and then the search-light is thrown upon the different groups of sculptures in a way that emphasizes their beauty. As it fell on the spirited figure of Franklin standing in the arched recesses of the Electrical Building, the bold lines of the composition were clearly revealed, while the fine figures of animals on their high pedestals along the water seem almost life-like in distinctness. The spectacle was wonderful.

The vast orderly throng of 150,000 swiftly moving people failed to encumber this spacious pleasure-ground. There was room for all without crowding.

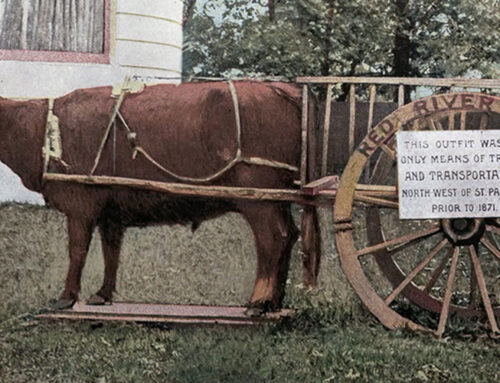

“The Gondola Landing, Art Palace” by Joseph Gleeson. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

Revelers waited to enjoy their turn

We had time to notice this while sitting upon the parapet waiting for a vacant gondola. These boats are not black, as in Venice now, but painted in various colors, as they were in Columbus’ day. Some of them, with high prows surmounted by swans’ necks and griffins, are reproductions of the state barges of ancient Venice, and others are of the ordinary size, gay with colored cushions and awnings.

On this gala night the gondoliers were arrayed in an old-time costume of striped red and white, the lion of San Marco emblazoned on their breasts and on their heads the curious cap of the fifteenth century. The night was warm and still, the lights gleamed on gayly clad forms which stepped in and out of the graceful boats as they came alongside the broad white steps, where revelers waited to enjoy their turn.

The dome of light burned on, the shining water plashed in the fountains, and, as our turn came, we floated beneath the bridges, where the shadows lay cool and deep. Under the bending Willows of the island were sleeping flocks of water-fowl, and among the Iris-leaves a swan lifted up his long neck from his wing, gazed at us in sleepy wonder and then sank again to repose. Up and down we floated by the vast white palaces, till the torches on the dome flared and were spent, till line by line the electric lights were extinguished, and we could stay no longer. “Buona sera, Signori, remember the gondolier,” murmured the gentle-tongued Venetian as he helped us up the snowy steps, and the first magical day of our sojourn at the White City was over.”

Leave A Comment