Charles Bowler Atwood, the most prolific architect of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, designed more than seventy-five buildings and structures, ranging from the stock to the sublime. In addition to great exhibition halls such as the Palace of Fine Arts and Anthropological Building, and the Peristyle, Casino, and Music Hall complex, Atwood is credited with:

Accounting Department, Agricultural Annex, Ambulance House (Midway), balustrades around lagoons and canals, band stands (3), barns (Exposition Company’s), Bicycle Sheds, bridges over lagoons and canals, Carpenter and Blacksmith shops, Charging Station (for electric launches), choragic monuments (2), Clow Sanitary Office, Clow Toilet Buildings, Conkey & Company’s Storeroom, Courthouse (police), Dairy Barns, Dairy Building, Electric Department Office, electric lamp-posts, entrance ways (13), Fire and Guard stations, flagstaffs (11), Forestry Building, Free Photograph Dark Room, Garbage Furnace, Gondola Repair Shop, Horticultural Greenhouses and Landscape Greenhouses, Hunters’ Cabin, Illinois Hospital, Training-School and Pharmacy, kitchen (Wellington Catering Company), La Rabida, Landscape Department House, Lowney Company Pavilion, Machinery Hall Annex, Machinery Hall Boiler House, Machinery Hall Shops, Oil House, Oil Pump House, Oil Signal House, Oil-tank Vault, Paint Shop, Perron, Photo Building and Annex, Plumbing House, police stations (Hyde Park and Woodlawn), Public Comfort, Pump House, rostral columns (6), Sawmill, Service Building, Sewage Cleansing Works, sheds on Van Buren Street pier, signal towers, silos (2), Staff House (4 models), Stereotype Building, Stock Barns, terminal railroad sheds, Terminal Station, Tool House, Wagon Sheds, Warehouse (United States Bonded), Warehouses B, C, D, E, F, G, H, and the Woman’s Pharmaceutical Building.

His death on December 19, 1895, at age the young age of 46, though shocking, apparently was not surprising to those in his professional circle who knew of his flagging productivity. The life and death of this brilliant architect was shadowed by mystery.

The stirring eulogy below, from the January 1896 issue of The Inland Printer and News Record, comes from his (former) boss and mentor, Daniel Burnham. A preceding editorial, “The Death of Charles Bowler Atwood,” summarized the architect’s contributions:

In the death of Charles Bowler Atwood the architectural profession has lost one more of those whose names have become known throughout the world. Atwood was a man of highly artistic temperament, and, though spasmodic in his work, but few years have passed in the last twenty-five when he has not attracted the attention of the profession by some brilliant achievement. His fortunate engagement as chief of design for the Columbian Exposition gave him an opportunity such as few architects have ever acquired to distinguish himself in exactly that line for which his teachings and study had fitted him.

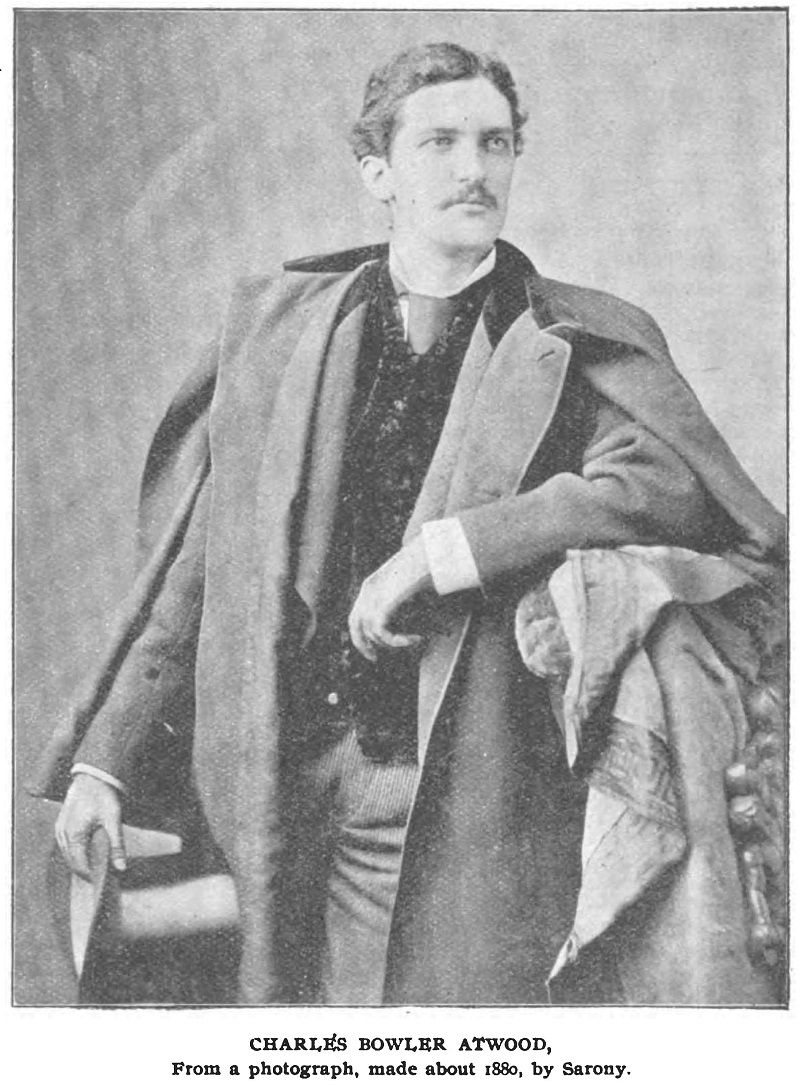

CHARLES BOWLER ATWOOD

BY DANIEL H. BURNHAM

Charles B. Atwood was born in Millbury, Massachusetts, forty-six years ago. He finished his general education in the Lawrence Scientific School of Harvard University. His architectural studies were commenced in the office of Ware & Van Brunt, of Boston, which firm was composed of Prof. William R. Ware and Henry Van Brunt, both of whom were then, as they are now, critical and scholarly men. He remained with this firm until he began to practice for himself, which was about twenty years ago, but he was not long his own master. Mr. Christian Herter, of Herter Brothers, the New York firm of finishers and decorators, had obtained an order from W. H. Vanderbilt, to build for him the great double dwelling house since erected on Fifth avenue. He needed someone to carry out his architectural ideas, and he employed Atwood for this purpose, who thus became the head of the architectural department of that establishment. During his connection with the Herters his duties finally led him to Great Barrington, Vermont, where he finished the house of Mrs. Mark Hopkins, which had been commenced by other designers. He spent some years in Great Barrington before returning to New York, where I found him in the spring of 1891.

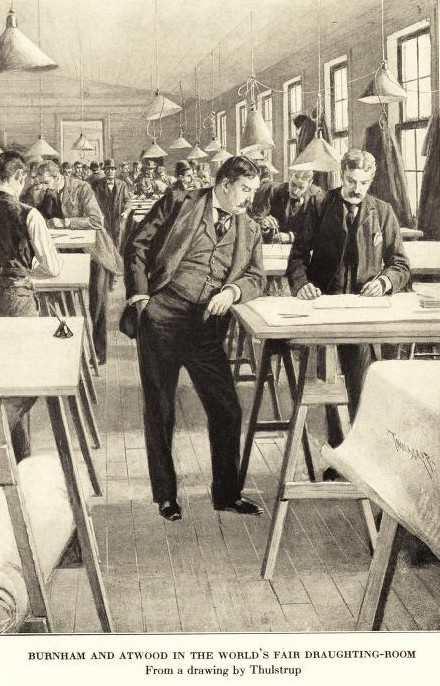

It will be remembered that John Root died in January. His death left me with a large private practice, and also with the responsibility upon me of designing and building the World’s Columbian Exposition. During the winter and early spring, therefore, I was casting about for an assistant to take Root‘s place. After negotiating with several persons eminent in the profession and not finding the man I sought, I received two letters, one from Professor Ware and one from Mr. Bruce Price, of New York, both of them calling my attention to Atwood and claiming for him the highest rank as an architect. On the strength of these letters I made an appointment with Atwood in New York ; something prevented his meeting me there, but he came to Chicago and called on me shortly afterward. Of course I was acquainted with much of his work, and the opinion of Professor Ware and Mr. Price weighed strongly in his favor. I have since thought, however, that all that preceded his coming had little weight with me compared with his own personality when I met him. I believe that had he, a stranger, introduced himself to me, the result would have been the same. I made an arrangement with him on the spot. We agreed that he should enter my private employment, but the need of him in the Exposition soon grew to be so evident that I placed him in that work instead of my own, and he joined my official staff at the end of April, 1891.

Atwood was tall and rather slender, of elegant figure and bearing; his hands and feet were delicate and shapely; his shoulders were square and strong; his head was remarkable for its beauty of outline; his eyes were gray and lustrous; his nose was aquiline; his under lip protruded slightly. His profile was of the type which has so often distinguished great poets of all lands, whether they were actors or orators, painters or sculptors, writers or architects. His voice was sweet and of that peculiar quality which opens the door of one’s heart to its possessor. Altogether, his presence was grateful to one’s love of grace and dignity and to one’s sense of those intangible elements we comprehend in the name of Gentleman. It was not his voice alone which threw a spell over the hearer, but his choice of words and the construction of his sentences as well. I often found myself marveling at his clearness and simplicity of statement, and the apt expressions which constantly issued from the mouth of this gifted man, even in his ordinary conversation.

After the Exposition was completed he came back to my private work and joined me as a partner in it.

From the commencement of his independent career he was much more interested in monumental works than in the lesser problems of architectural practice. He had been trained in a school of classic design, and although he occasionally used other styles, his successes were made when following most closely the Greek forms and feeling. He was fond of competitions and entered many of them ; in this field he won many prizes, some of them even of national importance. He was awarded the Public Library of Boston, but for reasons which I have never heard explained, the work was done by other hands. He won the competition for enlarging the City Hall in New York. The drawings made for this were admirable; his management of the design could scarcely be better. The city of New York, however, gave up the idea of enlarging the old City Hall and finally called for competitive designs to cover the entire property. In the published statement to the architects there were conditions which made it difficult for some of the eminent practitioners of the country to enter the competition with self-respect. While the final form of the document was still under consideration, and while it was still thought that the Commission would modify certain clauses in it, Atwood was hard at work on a design for the building. This design was elaborated far enough to fully show his intentions, but it was never sent in. In this work he placed no limit to his imagination, but gave it full play, and on paper he presented such a conception of combined architectural beauty and grandeur as has never been seen in any structure built by the hands of man. These drawings will be preserved and placed where they shall ever speak to the scholar of the great genius of our friend who has recently passed away. They exhibit the best he could do, and they prove his right to be called a master.

The Vanderbilt houses are distinguished for justness of proportion, and for taste and exquisite delicacy of ornament. It has been said that two houses in the city of New York will stand the criticism of time; this Vanderbilt mansion is one of them.

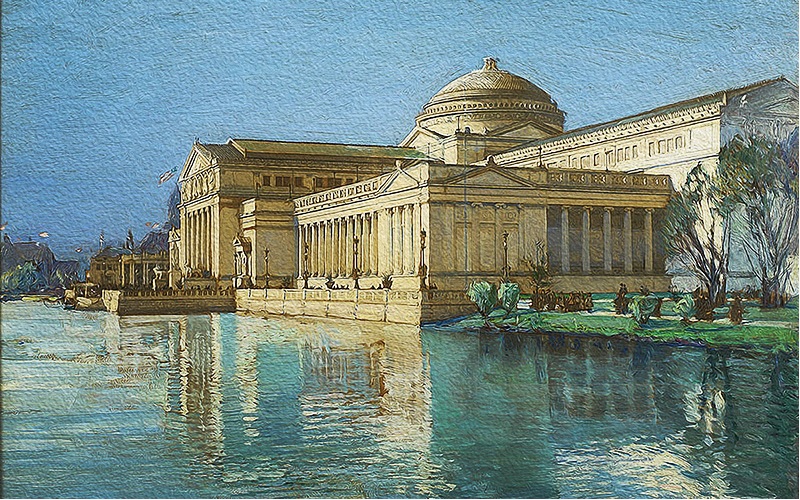

Atwood’s work in the Exposition is known to everyone. He designed the Art building, the Peristyle, the Terminal Station, the terraces, the bridges, the rostral columns, the Service building, the Forestry, and many minor decorative features. To his critical taste was largely due the final finish of the architecture of the Fair as a whole. One evening, late in the summer of 1893, I was in my private apartments in the Service building at Jackson park, when one of the most eminent artists of our day came in and threw himself upon the lounge, from which he sprang up with great excitement a few moments later, and seizing me by the shoulders said, “Do you realize the rank of Atwood’s Art Building among all the structures of the world?” and without waiting for a reply, he continued, “There has been nothing equal to it since the Parthenon.”

In our private work he designed a building in Buffalo, which is very beautiful, and is unsurpassed by the business structures of America, the Field retail store, the Youngstown Bank, and other buildings. During the last two years his health was such as to prohibit any steady concentrated effort, but his mind was always occupied with architectural problems, and in his professional work his whole interest centered. After his death we found a room of his house wherein the shelves, tables, chairs, and even the floor were covered with great piles of illustrations of buildings and details which had appeared during the last twenty years in architectural journals and other publications which he had cut out and was assorting for the purposes of his own study. He was a great user of books, and constantly referred to the measurements made by scholars, and to the drawings and comments of masters of our art. His mind was receptive to suggestion, but still when it came to the final design he was tenacious of his own convictions. As a draftsman I never met his equal; he worked with his left hand, and his execution was marvelously sure and rapid. After a sketch had been made by him there was very little improvement to be suggested.

He was of an honorable, charitable disposition, but, as most great artists have been, was a mere child in the practical things of life.

Atwood’s career has been a short one—too short, perhaps. But if one measures his success by what he has done in the brief four or five years just passed, surely no master at the end of his career has ever been able to point to higher or more valuable results. His designs will live, and will be the inspiration of eager students long after our century has taken its place in the shadowy past.

This is so full of wonderful information, thank you. I am a researcher of leaded glass lighting 1905-1920 and would be happy to hear who made the lighting in Atwood’s designs. I know Willy Lau was used by Burnham but perhaps others were commissioned too. Thanks. Colin Hansford leadedlamps.com

Hi Colin. My understanding is that all of the lighting for the fairgrounds, including all the exhibition halls, was done through a contract with the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company. Installation inside the Art Palace, which had more interior incandescent lights than any other building, began on August 24, 1892. Daniel Burnham’s report describes the lighting: “The picture galleries were illuminated with lines of light placed in screens which served as reflectors. These screens were 17 feet above the floor and seven feet from the walls upon which the pictures were hung. The lights were 8 inches apart in the screens, and so arranged that a brilliant illumination was cast upon the walls, but the lights could not be seen from the floor. These reflecting screens had been included in the Westinghouse contract, but after some discussion it was decided to use a more efficient though more expensive one than the contract had required, and a special arrangement was made for them.”