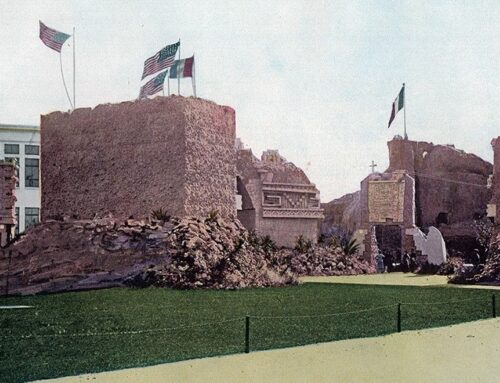

Swedes from Chicago and around the world celebrated Sweden Day at the World’s Columbian Exposition on July 20, 1893. Many of the festive events took place at the beautiful Swedish Building. Nearby stood the Swedish Restaurant, which served as another site for Swedes to gather on the fairgrounds and as a concession to showcase Scandinavian fare to visitors from around the world.

The Swedish Restaurant (also called the Swedish Café) was run by Robert Lindblom (1844-1907), a prominent Swedish-born trader on the Chicago Board of Trade. Appointed by Chicago Mayor Dewitt Cregier to the city’s initial World’s Fair executive committee, Lindblom later served a resident acting commissioner for Sweden prior to the arrival of commissioners from the homeland. A prominent member of Chicago’s Swedish community, Lindblom asserted his Scandinavian pride into bid to host the Columbian Exposition by remarking that “Columbus did not discover New York, Washington, or St. Louis any more than he did Chicago. He did not even discover North America at all except theoretically.” [Cohn, 46]

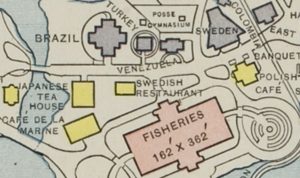

A map of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition grounds in the area around the Swedish Cafe. [Image from Johnson, Rossiter A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Volume 1 – Narrative (D. Appleton and Co., 1897).]

An old tavern in southern Sweden

The Swedish Café was located just outside the north entrance to the Fisheries Building. Across the path called Naval Way to the north stood the Brazil, Turkey, and Venezuela government buildings; the Swedish Building was 500 feet northwest of the café. Nearby restaurants of comparable size included the Japanese Tea House and Café de la Marine (Marine Café) to the west and the Polish Café and the significantly larger New England Clam Bake to the east.

The Swedish Restaurant concession was granted to Lindblom only a little later than theses other nearby restaurants, but his structure is not shown in several earlier maps and bird’s-eye views of the fairgrounds and is listed simply as “Outside Concession” in another. It is labeled as “Swedish Restaurant” in an April 1893 fire insurance map, suggesting that the Swedish Restaurant building was one of the last buildings to go up in this section of the fairgrounds.

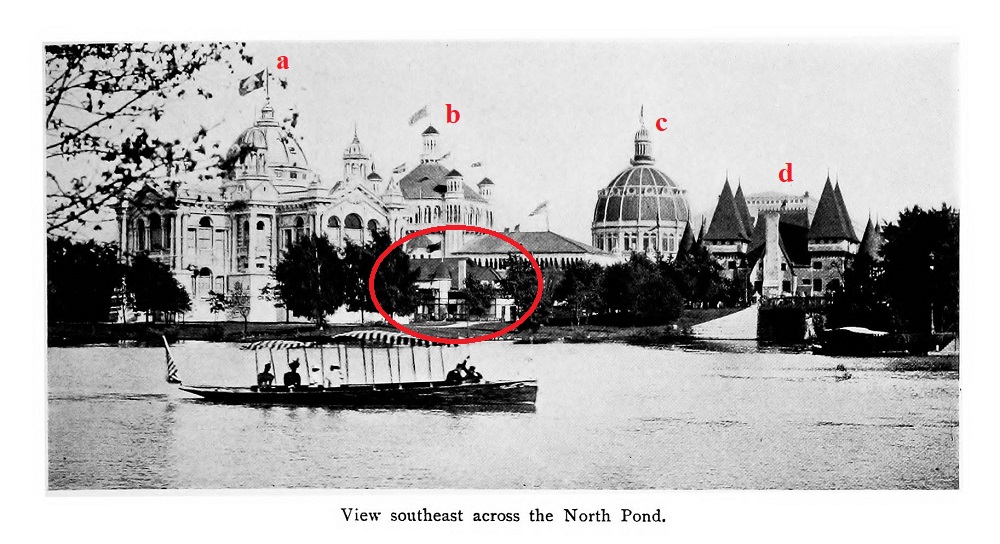

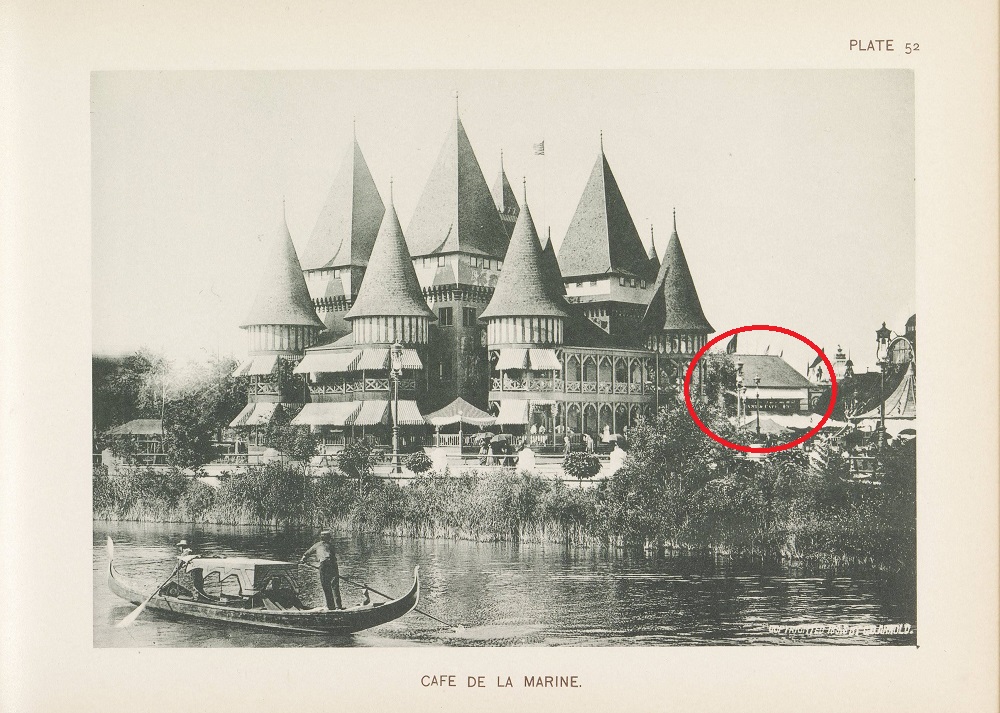

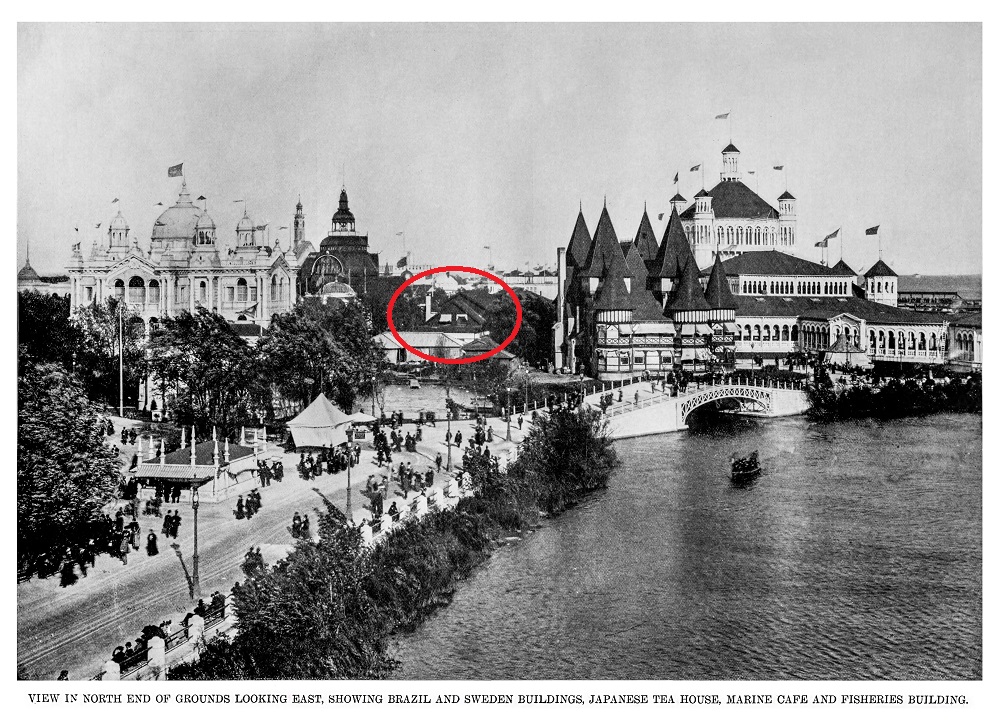

Swedish architect Gustaf Wickman (1858-1916) designed the Swedish Restaurant, as well as the Sweden Building and adjacent Posse Gymnasium. He constructed the café building using wood frame with a shingle roof and designed it to look like an old tavern in southern Sweden. The restaurant is not featured in many photographs of the Fair, though parts of the structure can be seen in vistas showing the nearby imposing structures of the Fisheries Building or Café de la Marine.

View southeast across the North Pond, showing (left to right) the (a) Brazil Building, (b) Fisheries Building, (c) U.S. Government Building, and (d) Café de la Marine. [Image from Johnson, Rossiter A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Volume 4 – Congresses. D. Appleton and Co., 1898.]

The Café de la Marine, showing a section of the Swedish Restaurant on its east side (right). [Image from Arnold, C. D.; Higinbotham, H. D. Official Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Press Chicago Photo-gravure Co., 1893.]

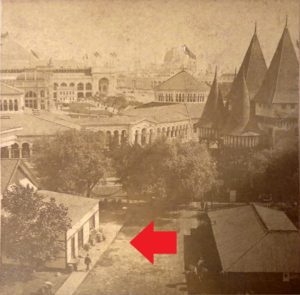

View looking northeast across the north of the Lagoon. The roof of the Swedish Restaurant can be seen in the center of the photo, with the tower of the Swedish Building to the north (left) and spires of the Café de la Marine to the south (right). [Image from Campbell, James B. Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume I. M. Juul & Co., 1894.]

A view looking south from the Brazil Building, with the Swedish Restaurant in the center left and the Japanese Tea House in the center right. The Fisheries Building and the Café de la Marine are in the left and right background, respectively. A dining area underneath the two trees south of the café is visible. [Image from Kilburn stereoscope card No. 8299. The Great White City, Columbian Exposition.]

No one but a Swede has ever yet succeeded in eating it

The concession was described as a “very pleasant restaurant, where Swedish dishes are sold, and [where] one is waited on by bright-faced Scandinavians.” [Shepps, 334] In this and other restaurants serving international meals, “visitors from foreign countries may be served their native dishes by native waiters, and curious Americans can learn much of the customs of other countries.” [White, 558] A story below challenges this portrayal of authenticity.

Customers could dine al fresco at tables under the trees or under a tent. The restaurant served traditional Swedish fare. One guide offered these details of the “thoroughly Swedish” menu:

“Guests may here enjoy, if they can, smoked reindeer, baby sausages, craw-fish tails, raw ‘delikatess,’ herring, fried stromming, smoked goose breast, reindeer tongues, and ‘graflax,’ a conglomeration that no one but a Swede has ever yet succeeded in eating. Swedish ‘brannvin,’ a potato whisky, is there to wash down this bill of fare, which in addition to the articles named includes, of course, many common to the tables of all people.” [A Week at the Fair, 168] With gross sales of $86,099.50, the Swedish Restaurant business under-performed the nearby New England Clam Bake ($89,884.05), Polish Restaurant ($112,472.72), and Café de la Marine ($173,613.05). [Higinbotham, 484] In honor of Sweden Day, we offer three stories about the kind of service World’s Fair visitors experienced at the Swedish Café.

Not a Desirable Customer

The first story comes from Teresa Dean’s White City Chips (Warren Publishing Co., 1895). This rather snobby columnist for the Chicago Daily Inter Ocean records her experiment to test the manners of various restaurant waiters. Along the way she discovers “conclusive proof that you cannot gauge civilization or uncivilization by classes or races.”

Here are some of the cross-wired samples which do so mix up and blur one’s ideas: Some one suggested to me that I squander a $10 bill in looking into the truth of how guests at the different restaurants and cafes get treated when they give a light order—an order that the average American would give in visiting the Fair through the day when he expects to dine at home or at his hotel. I was not feeling the need of refreshment just then, but thought I could drink a cup of coffee. I went into the Swedish restaurant, or rather I went under the tent outside, where there were pleasant, cool-looking seats. I sat down at a table neatly set with white linen and bright silver. A waiter came up to me very promptly and very business-like to take my order. I said:

“A cup of hot coffee.”

“What more?” asked the waiter.

“Nothing.”

Then he said in very uncertain English that I would have to go to another table, that these were dining tables. His manner had been very suave when he first came up, but he grew very cold and indifferent, and indicated with a wave of his arm where I could get a cup of coffee.

I went over there and took a seat at a table without any cloth and no bright silver. No waiter came up promptly and business-like this time. I waited a few minutes and then motioned for one. He came up reluctantly, and when I said “coffee” looked at me suspiciously, as if he thought I had some luncheon hidden away somewhere. He brought the coffee and placed it on the table and went off for sugar, cream, napkin and spoon, presumably. He returned with cream, then hunted around for some sugar and didn’t find it. He disappeared and was gone so long that I sent another waiter for it, and told him to bring a napkin. He said they had no napkins for the lunch tables. I said that I would pay extra for it. That made no difference. There were no napkins for that table, and he went for the sugar. The first one returned first, but had no spoons. I told him that I did not care for the coffee; it was cold. He shrugged his shoulders, but did not offer any apologies for the delay, nor to get some that was fresher. It was plainly evident that any one who would order a cup of coffee was not a desirable customer. I then decided that I would try that cup of coffee in the next one, which happened to be the Polish restaurant. I met with exactly the same reception, and did not drink that, either.

Dean goes on to note that her “fast-forming theory about foreign waiters received a blow” when the French waiter at the nearby Café de la Marine provided impeccable coffee service.

A Heap of Confidence in Human Nature

The second story comes from Benjamin Cummings Truman’s History of the World’s Fair (Mammoth, 1893) and shows that even visitors planning to order a meal at the Swedish Restaurant could receive less-than-satisfactory service.

The Swedish cafe people have brought with them a pleasant old-world custom of setting tables for their guests around under the trees on the green turf, where the cool winds of heaven may fan their fevered brows and frappe their soup before the waiter gets around with a spoon to eat it with–for of all leisurely creatures under the sun the Swedish waiter takes the lead.

A couple sat down at one of these out-of-door tables one day, and after due deliberation a waiter appeared and took their order; then he disappeared. Just as the two were giving up all hope he came back with part of the order and set it down. After an interminable wait his nature prompted him to bring bread. The knives and forks appeared next, the order of procession impressing his charges with the idea that eating a Swedish meal was like reading Hebrew, and it was necessary to begin at the end and work forward. When everything was on the table, and in response to repeated tearful entreaties he had even brought beer, he made another disappearance that threatened to be final.

The couple finished their meal, chatted pleasantly for awhile, had a quarrel and made it up, talked in a desultory fashion about the Fair and the weather, and looked for the waiter high and low. Finally the man caught another waiter and tried to send him after the first. After the man had minutely explained what he wanted the waiter said he didn’t speak English. Then the woman came to, the rescue.

“Let’s just get up and walk off, then they’ll chase us, and you can pay,” she suggested.

“All right,” said the man, who was becoming desperate.

They walked off a few hundred feet and not a soul moved. Then the man came back, and as he was returning caught sight of his waiter around a corner of the cafe.

“Ah,” said the waiter with a beaming smile, after the man had informed him in a vindictive manner that he wished to pay his bill. “Ah, I thought you had gone; I thought you would come back to-morrow, eh?”

“Well, you’ve got a heap of confidence in human nature,” said the man as he fished around his pockets for an extra dime. “I want to give you that,” he said, “and I want to impress it on your mind what it’s for; it’s for your inattention.”

No Sweden For Her

The final amusing story, from the October 1, 1893, issue of the Chicago Daily Tribune, reminds us that much of the World’s Fair was an illusion.

A lady and gentleman who have been “doing” the Fair since it opened sat down to luncheon in the Swedish Café, where the waiters are supposed to be direct importations from the land of the Swedish nightingale. At least, they are dressed in the costume of the peasantry of that country.

Rye bread and Swiss cheese and beer was the order given, for these two people are doing the Fair as they find it. They were waiting for their luncheon and the woman talked of the beauty of the girl who had gone for it. She wondered if that girl ever saw, ever heard Christine Nilsson, and a lot of other things. The man suggested that his companion might ask the girl and thereby pick up a story.

“But she probably cannot speak English. She is not long from her fatherland, poor thing, and I don’t like to embarrass a waiter.”

“You might try,” said the man.

So when the order was served the lady looking at the waiter, who by the way, was a brunette, said: “I thought Swedish girls were blonde; is it not so?”

“Most of them are,” was the quick reply in good English.

Encouraged, the lady continued: “Tell me, my good girl, how long have you been away from your native country?”

“About nine years.”

The lady, somewhat cooled: “Nine years from Sweden?”

“Sweden? Who said I was from Sweden?”

“Then where is your home?”

“Milwaukee avenue. Sixty cents, please” (to the gentleman).

And the lady vowed that she would not indulge in any more musings over the foreigners at the Fair.

REFERENCES

Cohn, Scotti It Happened in Chicago. Globe Pequot Press, 2009.

Dean, Teresa White City Chips. Warren Publishing Co., 1895.

Higinbotham, H. H. Report of the President to the Board of Directors of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Rand, McNally & Co., 1898.

“No Sweden For Her” Chicago Daily Tribune Oct. 1, 1893, p. 35.

Shepp, James W.; Shepp, Daniel B. Shepp’s World’s Fair Photographed. Globe Bible Publishing, 1893.

“Sweden at the Exposition” Campbell’s Illustrated History of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Volume II. M. Juul & Co., 1894, p. 393.

Swedish Catalogue I. Exhibits. World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893. Ivar Haeggström, 1893.

Truman, Benjamin Cummings History of the World’s Fair. Mammoth, 1893.

Wade, Stuart C.; Wrenn, Walter S. The Nut Shell: The Ideal Pocket Guide to the World’s Fair and What to See There. Merchants’ World’s Fair Bureau of Information Co., 1893.

A Week at the Fair, Illustrating the Exhibits and Wonders of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Rand, McNally & Co., 1893.

White, Trumbull; Igleheart, William World’s Columbian Exposition Chicago, 1893. J. W. Ziegler, 1893.

Leave A Comment