Author Julian Hawthorne visited the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Reprinted below is the third part of Julian Hawthorne’s “The Lady of the Lake” about his June visit to the fairgrounds and published in the August 1893 issue of Lippincott’s Magazine. The previous installments can be found in Part I and Part II.

[NOTE: By today’s standards, some of Hawthorne’s remarks about the Midway Plaisance and citizens of the international villages sound racist. It was not uncommon for commentators of this era to describe Asian and African displays at the Fair as “savage,” “uncivilized,” or “dirty” (Hawthorne repeats this word seven times in one paragraph!). Our reprinting of this 19th-century writing does not imply endorsement of his views.]

THE LADY OF THE LAKE

by Julian Hawthorne

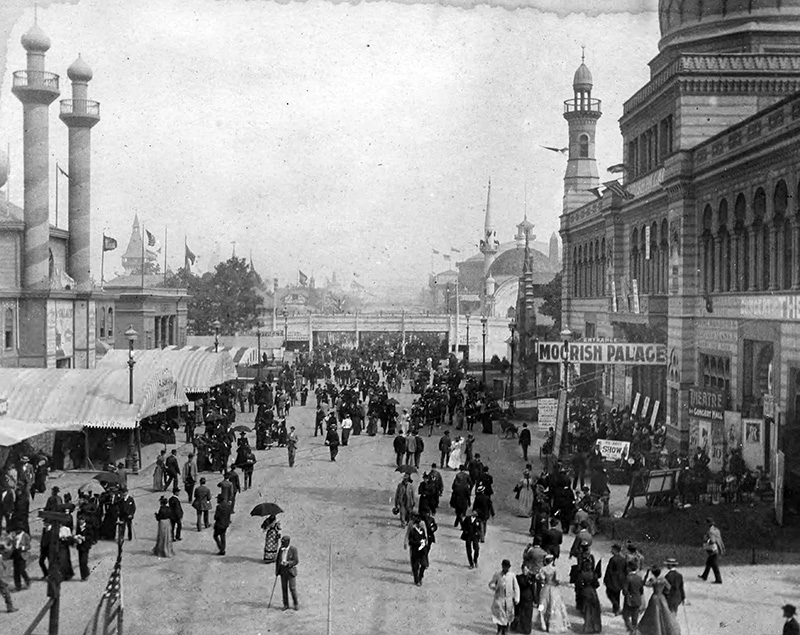

The Midway Plaisance by T. de Thulstrup. [Image from Burnham, Daniel Hudson; Millet, Francis Davis The Book of the Builders Vol 1. No 3, May 5, 1894.]

The

Midway Plaisance is a sort of curiosity-shop, in which the curiosities are mainly men and manners. There are also booths, cafes, lath-and-plaster “villages” and temples, and various shows of a more or less seductive aspect. The value of the Plaisance—save as a mere lounging-ground and beer-garden—lies in its Oriental and East Indian features. We Westerners cannot help being interested in Turks, Arabs, Numidians, Cingalese, Javanese, Syrians, and even in Chinese and Japanese, when they are not naturalized American citizens, or “cheap labor.” There are plenty of all these here, in their own dirty, beautiful costumes; with their brown faces, their dark, shining, impenetrable eyes, their queer shoes, sashes, caps, turbans, their shrugs and gestures, their incomprehensible grunts, gutturals, gurglings, clucking, and chattering.

In the recesses of a shadowy Aladdin’s Cave of a booth in the

Turkish Bazar you may see Ali Baba Mustapha Ben Edin, with a dirty white turban, dirty gold-embroidered caftan, dirty crimson silk girdle, dirty voluminous trousers, dirty up-curving slippers, dirty old face and hands and long gray beard, and an expression in the wrinkled eyes and long nose of world-weary, fatalistic, Mohammedan sagacity. There he squats, at the receipt of custom, prepared to charge you fifty dollars for a ten-cent necklace, and to chaffer about it, amidst hookahs and coffee, from dawn to sunset.

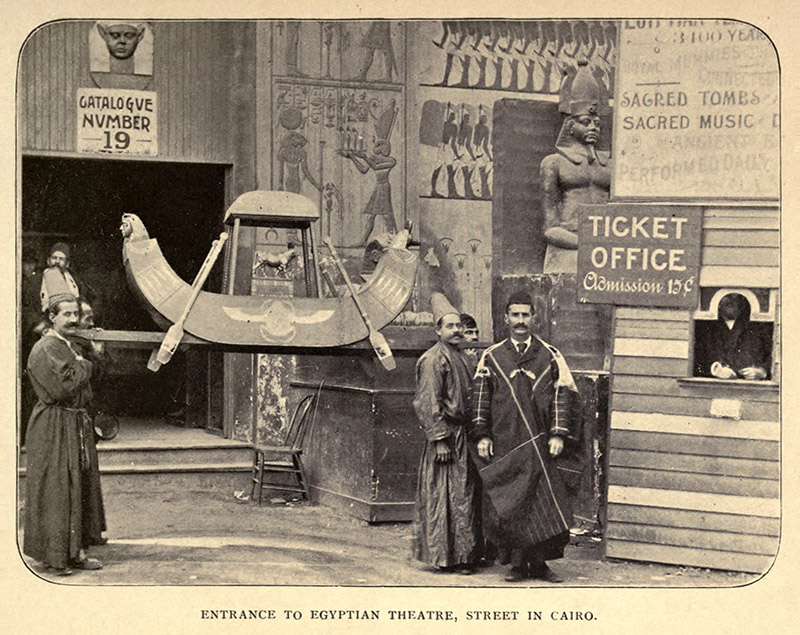

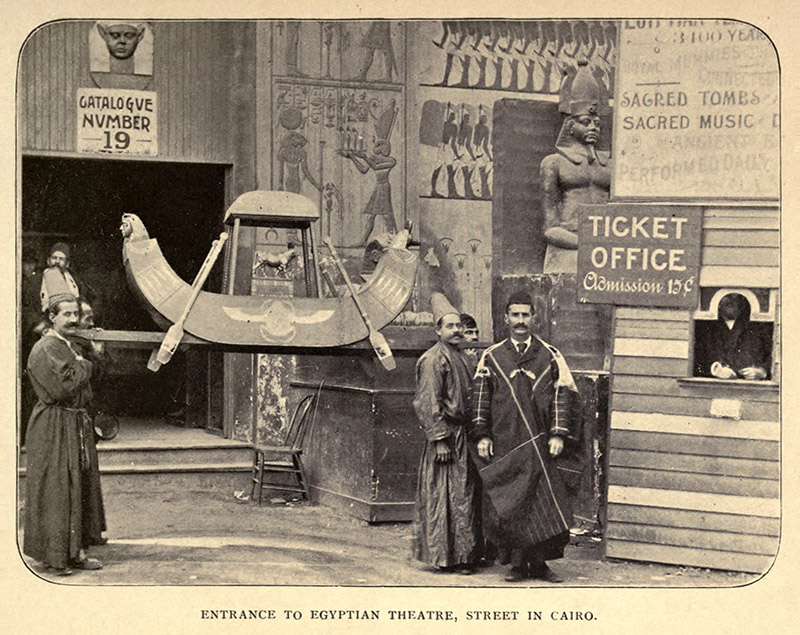

Entrance to the Egyptian Theatre in the Street in Cairo exhibit. [Image from Butterworth, Hezekiah Zigzag Journeys in the White City (Estes and Lauriat, 1894).]

In the

Temple of Luxor, in the

Cairo Street, twenty-five cents will admit you not only to the presence of twenty or thirty Pharaonic mummies, made of wood, rigid in their sarcophagi, but to that of a soft-eyed, soft-skinned, Oriental maiden, Scheherazade by name, who plays with tapering brown fingers on a lute, and answers questions courteously, smiling with a delicate, voluptuous mouth.

In the

Javanese village, which is a

bona-fide Javanese village, with bamboo huts built on the spot by the natives themselves, you may see and exchange signs and sounds with the latter, as they dawdle about in the sunshine with their dusky bare legs, and feet scuffling miraculously in shoes which have nothing but the scuffle to hold them on withal.

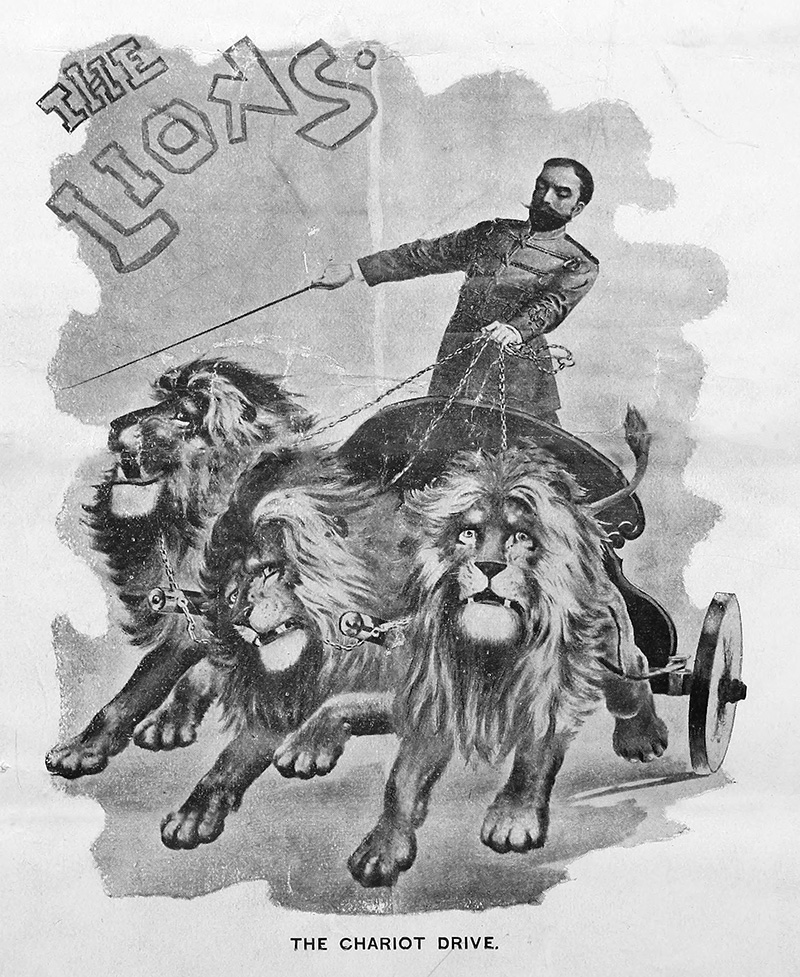

Across the way, half a dozen Asiatic lions are roaring in an open cage, and a knot of Arabs stand watching them, with the regretful, sentimental air of wandering pilgrims to whom a chance strain of music brings back thoughts of home and mother. Yonder undulates a Constantinople

palanquin, containing a fat daughter of the West, and supported by a couple of swarthy, grinning Mohammedans. And through all, dominating all, alien, investigating, push and throng the shrewd, humorous, curious, earnest, frivolous Americans, to whom the mighty past is a fairy-tale, and the mysterious future a game of brag.

There has been much palaver about management, conveniences, abuses, Sunday opening, and so forth. Some complaints are justified, others are not: such abuses as exist are mostly the result of inevitable inexperience or accident, and will probably have been done away with by the time these words reach the reader. Other criticisms, such as the statement that any other expense than the fifty cents admission is involved in seeing the Fair, are wholly without foundation. Except that it costs twenty-five cents extra to take the elevator to the top of the main building, and fifty cents for a ride in a gondola, the whole exhibition, including the music and the illuminations, is free. As for the Midway Plaisance, though connected with the Fair, it is in the nature of a private enterprise; you must pay half or a quarter of a dollar to go into the various peep-shows; and whatever merchandise you buy, you pay for as a matter of course. But a five-dollar bill will cover all expenses necessary to enable you to see everything, even here. And you can see enough without paying anything at all.

On the other hand, there is no denying that some of the gatemen and guards are ruffians, some are thieves, and some are both combined.[1] But these are being removed as fast as they are found out. Games at cross-purposes occasionally occur between the Directors and the Commissioners, and between separate officials, but that is only because both sides are anxious to do their duty, and lack, not good will, but instruction. Again, the completion of the Buildings and the exhibits was much behindhand, and heaps of rubbish and forests of scaffoldings do at the present writing (June 1) mar the beauty and convenience of the spectacle. But the entire enterprise is so stupendous and unprecedented that the only wonder is, it should be ever completed at all; and in a month from now it will probably be entirely ready.

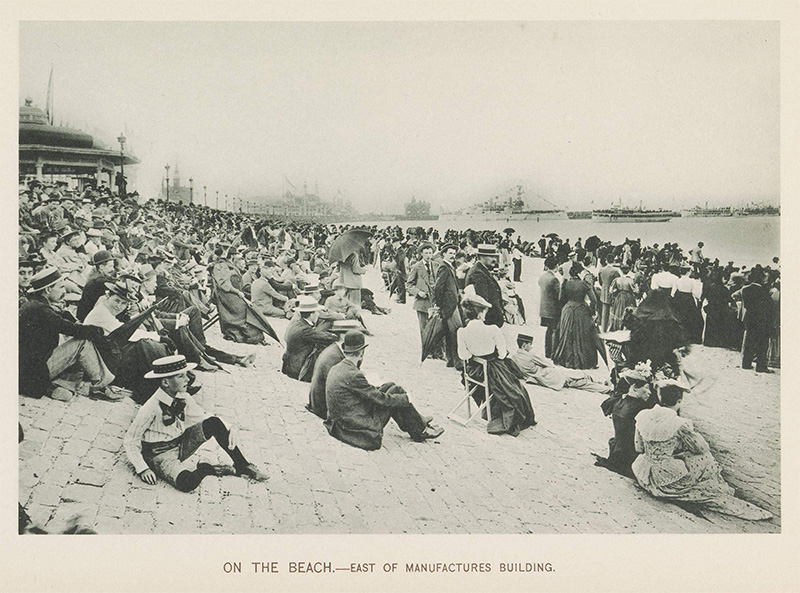

Scaffolding around the unfinished Ferris Wheel on the Midway in the early weeks of the 1893 World’s Fair. [Image from the Chicago History Museum, ICHi-002436.]

In fact, the only serious objection I can think of is restricted to the character of the Chicago climate. This is entirely at the mercy of the winds. The winds blow, and blow hard, nearly all the time, and the air is apt to be so full of dust that breathing and seeing become difficult. But the worst of it is, that as soon as the wind begins to blow from the Lake, the temperature sinks from twenty to forty degrees, and loses no time about it either: in an hour or two you may change from perspiration to shivering. Moreover, the heat, when it is hot, is very hot, and is apt to be muggy; while the cold is the very most comfortless and exasperating cold that I ever experienced. Yet days do intervene which are nearly perfect, and which make you willing to forget all the hard things you have felt about the Chicago climate. And it is perhaps unjust, while this exceptional spring is as yet hardly over, to grumble about the weather. Other places besides Chicago have suffered this year. The coming summer may redeem the reputation of the year.

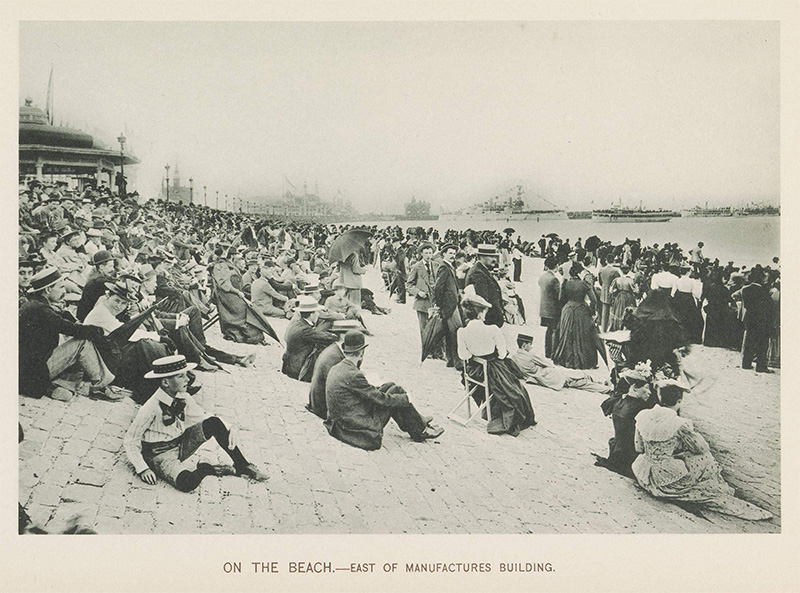

Visitors at the Fair cool off “On the Beach East of Manufactures Building,” a photograph by C. D. Arnold. [Image from Arnold, Charles Dudley; Higinbotham, Harlow Official Views of the World’s Columbian Exposition (Chicago Photo-Gravure Co., 1893).]

NOTES

1. Hawthorne’s criticism of the Columbian Guard is unusual. Many visitors recorded enthusiastically positive impressions of the Guard as being comprised of polite and helpful gentlemen and a model urban police force.

Leave A Comment