Author Julian Hawthorne visited the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Reprinted below is the second part of Julian Hawthorne’s “The Lady of the Lake” about his June visit to the fairgrounds and published in the August 1893 issue of Lippincott’s Magazine. Part 1 can be found here.

THE LADY OF THE LAKE

by Julian Hawthorne

The Palace of Fine Arts depicted in “Art Palace from the Southwest” by the Poole Brothers. [Image from Vistas of the Fair (Poole Bros., 1894).]

Meanwhile, it is striking, stimulating, and at times wonderfully telling. It is also quite new. The science of color is being thoroughly overhauled, and investigated afresh. None of the old smooth, conventional effects are any longer trusted. The departure is chiefly observed in landscape and in studies of the nude. Some of these affect one, at a first glance, as strange, unreasonable, or even grotesque and impossible. Nevertheless, seen from a different point of view, or in another light, they occasionally shine forth like life itself. The theory seems to be that the artist shall prepare the conditions of a problem which shall, literally viewed, appear as meaningless as a face of rock on a mountain-side, when seen near-to. But given the right combinations of light, position, and atmospheric peculiarity, together with sympathetic imagination on the spectator’s part, and it all at once kindles into a startling and delicious reality.

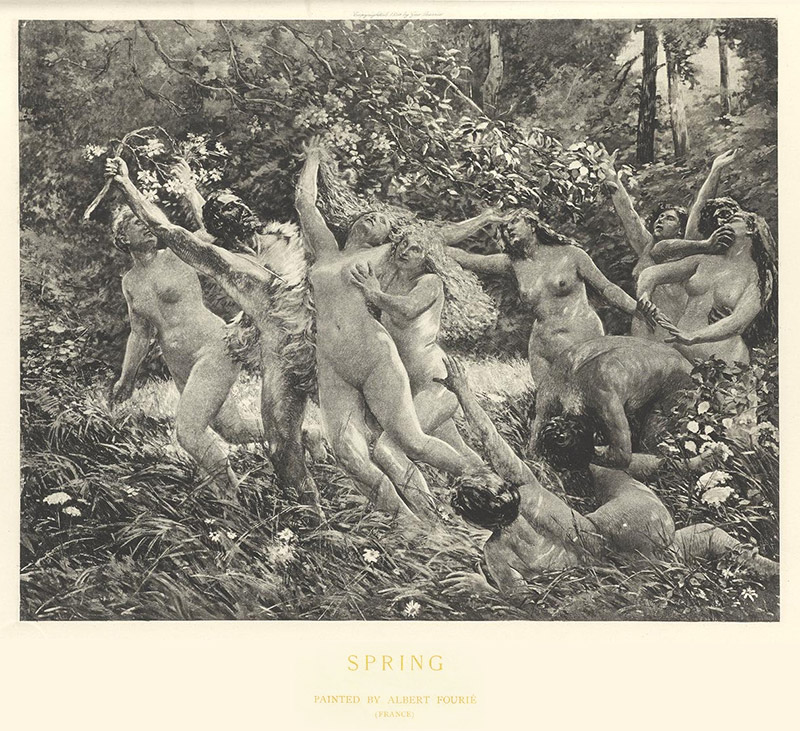

Albert-Auguste Fourie’s Spring [Image from Walton, William Art and Architecture (G. Barrie, 1893).]

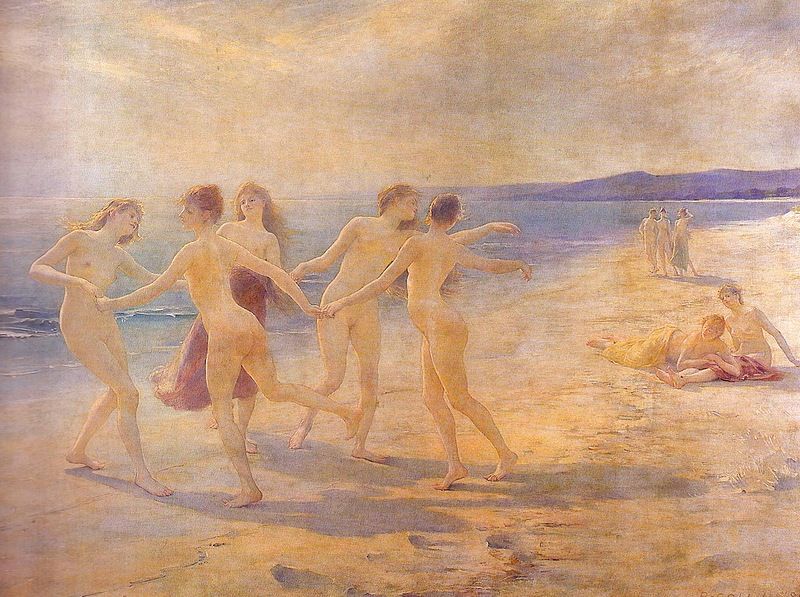

Raphaël Collin’s Au Bord de la Mer (1892), showing nymphs dancing on the sea shore, was exhibited in the French section of the Palace of Fine Arts.

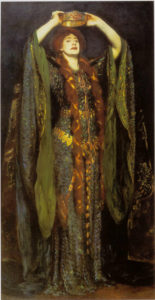

In a room in the East Pavilion [1] there are several large canvases of the nude which arrest attention and compel criticism. One represents a group of drunken nymphs and fauns romping in boisterous nakedness through the glades of a summer forest. There is great vigor in the design: but the color seemed inexplicable until, turning as I was leaving the room by the opposite door, I caught a glimpse which gave me the impression that the whole rout of wild creatures were plunging forward through the frame of the canvas in living abandonment.[2] Another picture, of sea-nymphs dancing on the sands of a sun-steeped ocean, is remarkable for its tone.[3] It is easier to see than the other, but less powerful. Elsewhere, there is a really tremendous portrait of Ellen Terry, as Lady Macbeth, holding the blood-stained crown over her head.[4] The whole composition, with the exception of the ghastly white face and arms, is a study of peacock blues and greens. It is so in tensely rich and strong that everything else in the room looks feeble and colorless. You cannot look long at it without exhaustion.

John Singer Sargent’s Portrait of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth (c. 1889) from the Tate Gallery, London.

Some of the most novel attempts in landscape are in the western wing of the great building. The artists of Northern Europe (with the general exception of the Germans themselves, who are uniformly academical and monotonous) are singularly bold and independent in their methods of color. They paint things which cannot be painted. But the attempts are salutary nevertheless. They are an advance. These suns, these waters, these meadows and rocks, have thought and meaning in them, in spite of their rainbow audacity. We shall hear more of these painters, or their successors: the crudities will disappear, and the lusty, vital truth shine out unveiled.

No one can help noticing the frankness and more than pagan un-reserve with which contemporary artists are treating the nude, both in painting and in sculpture. It is a wholesome change. Self-consciousness only can be immodest. “Beauty,” says Emerson, “doth limbs and flesh enough invest.”[5] Veils do but call attention to what is veiled. We do not want our delight in art, which is a pure delight of the soul, vitiated by the intrusion of conventional prurience and prudery. Make the expression clean, and let the rest go.

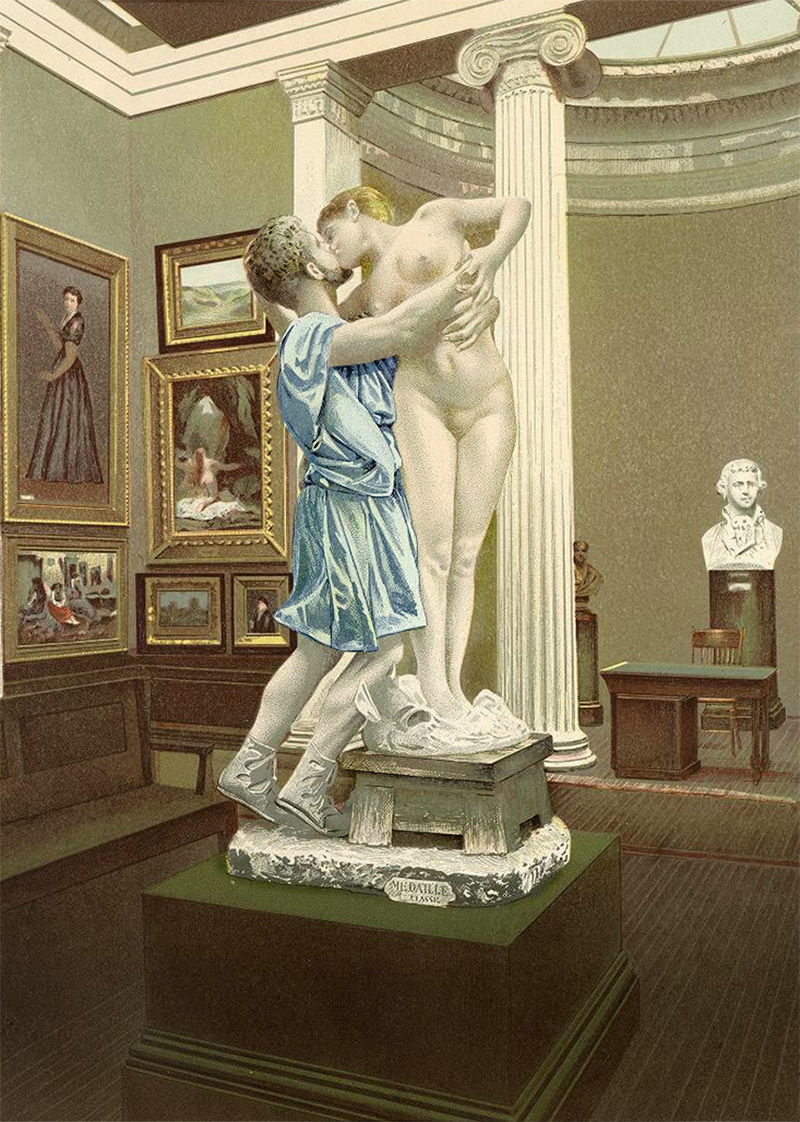

A painting of Pygmalion and Galatea, a tinted sculpture by French artist Jean Léon Gérôme, shows an example of nude sculpture. The work was on display as part of the U.S. Loan Collection in Gallery 38 of the Palace of Fine Arts. The sculpture is now housed in the Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California.

Touching contemporary sculpture, there is a word to be said. It is often beautiful, graceful, and clever; but it is seldom or never so satisfactory as the best antique. We get tired of it sooner or later; whereas we grow up to the antique, and never grow beyond it. The Venus of Milo, the Discobolus, the Borghese Achilles, and many others, rest, educate, and invigorate us forever. This cannot be said to be the case with modern statues. Why not?

The reason, it seems to me, is, that modern statues express too much. The sculptor tries to import into his marble what that medium of thought is not qualified to convey. Even the ancient Egyptians were nearer right than we are.

The face is the key-note of modern statuary. The action of the figure follows the meaning of the features. Until we see the latter, we do not understand the figure. This is asking too much of marble: it should be reserved for canvas. A statue never should portray a mental problem or condition, and its action should never be progressive. It should be so posed that it might retain that pose forever: the pose should be a consummation, never a transition. The ancients were right, too, in neglecting the face, and making the mere contours and attitude of the body satisfy the spectator’s need. They wrought in an age when the soul was far more harmoniously interwoven with the body than is the case now, and when, consequently, the body could express all that sculpture should attempt to indicate. The point may seem subtle, but it is of profound significance,—is far too significant, indeed, to be more than noted in an essay mainly discursive, like this.

Examples of figural sculptures in the Fine Arts Palace. [Image from the Keystone-Mast Collection, UCR/California Museum of Photography, University of California at Riverside.]

NOTES

1. The East Pavilion of the Palace of Fine Arts housed the both French exhibits and U.S. loans collection.

2. Hawthorne is likely describing the painting Spring by Albert-Auguste Fourie (1854-1937), which hung on the east wall of Gallery 57 of the French section. The current location of this vivacious work is unknown. Hawthorne expands upon this painting in his Humors of the Fair (E. A. Weeks, 1893) “At the end of the room is that design of a boisterous rabble of drunken bacchantes and fauns bursting into a forest glade in naked abandonment. An effort has been made to get novel effects in the flesh-tints; they have a sort of plum-like bloom on them, and the sun and shadows fall upon them through the overhanging branches. The figures are of a heavy and gross type, the rather by contrast with the refinement of type of the girls dancing on the beach; and I must admit I see no sense and little beauty in the picture. It means nothing, and I question the artist’s success in his effort to secure new effects.”

3. The painting that Hawthorne describes as “sea-nymphs dancing on the sands of a sun-steeped ocean” may be On the Sea Coast (Au Bord de la Mer) by French painter Raphaël Collin (1850 –1916), which hung on the north wall of Gallery 57 in the French section. Art historian William Walton wrote that “Collin’s nymphs dancing on the sea shore are pearly and opalescent and elusive to a surprising degree.” [Walton, William Art and Architecture, George Barrie & Son, 1893, p. 37]

4. Sargent’s Portrait of Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth (c. 1889) is 87-by-45-inch oil painting that hung on the west wall of Gallery 3. The painting currently resides in the collection of the Tate Gallery, London. For more on this and others works by Sargent’s works, see our post “John Singer Sargent at the World’s Columbian Exposition.”

5. Ralph Waldo Emerson’s poem “Painting and Sculpture” reads:

The sinful painter drapes his goddess warm,

Because she still is naked, being dressed:

The godlike sculptor will not so deform Beauty,

which limbs and flesh enough invest.

Leave A Comment