Darran Anderson’s essay “World’s Fairs and the Death of Optimism” (citylab.com, October 3, 2018) addresses the fading luster of World’s Fairs and uses some examples from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago to illustrate his point.

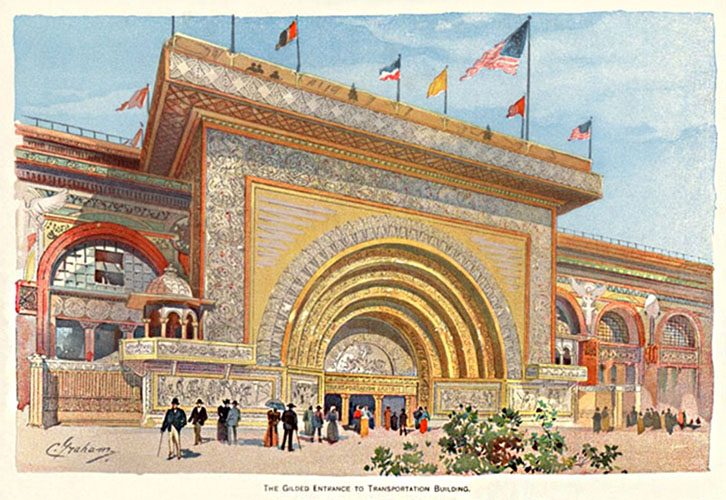

“World’s Fairs fell from grace,” writes Anderson. “Who could blame nostalgia towards witnessing the Crystal Palace, the head of the Statue of Liberty in a Parisian park, the extra-terrestrial Trylon and Perisphere, or the Tower of the Sun? This was bolstered by the fact that many of the greatest buildings, like Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan’s Transportation Building of 1893 with its famed Golden Door, had been demolished and so attained a lost perfection in memory. World’s Fairs seemed to suit children, who would be swept up in the spectacle of monorails, geodesic domes, and Ferris wheels.”

Anderson goes on to write that World’s Fairs depended on “narrow entrenched aristocratic and WASP-ish bands of society,” and that “attempts to address the chronic under-representation of women” at the Columbian Exposition “only highlighted the inequity.” He notes the case of Sophia Hayden, architect of the Woman’s Building who was “sacked by a committee of rich socialites for opposing their continual interference” and the challenges faced by the White Rabbits, a group of young female sculptors working for Lorado Taft on the fairgrounds.

Is optimism dead? There is much to lament about how many people were mis-represented and under-represented at the World’s Columbian Exposition—notably women, African Americans, Native Americans, non-Europeans on display along the Midway, and immigrant workers who built the White City. There is much to lament about how women, people of color, and immigrants are treated today. However, many World’s Fair enthusiasts remain inspired by the spirit of hopefulness and the confidence in a better future that flourished in Chicago during the summer of 1893.

The luster of the Dream City will only fade if we let it.

[…] gestrichen – daher wurden sie gemeinsam als „Weiße Stadt“ bezeichnet. Die Ausnahme war die Transportgebäude am östlichen Ende des Ehrenhofs, der in leuchtenden Farben bemalt und mit Gold vergoldet […]