The Toledo Museum of Art (TMA) currently has an exhibit commemorating the 200th anniversary of the Libbey Glass Company. Celebrating Libbey Glass, 1818-2018 features several pieces showing the Toledo glassmaker’s contributions to the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.

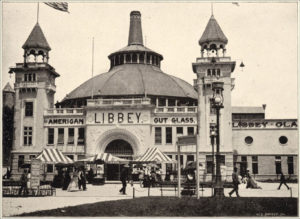

The Libbey Glass Works building on the Midway Plaisance. [Image from Views of the World’s Fair and Midway Plaisance (Conkey, 1894).]

The TMA exhibit features a framed lithograph (sadly, a reproduction) of the Libbey factory at the 1893 World’s Fair, designed by architect David L. Stine. The original watercolor presumably is held in the TMA collection. Displayed in a frame below on the same wall are a set of seven blue ribbons awarded to the Libbey Glass Company for excellence in glass blowing, various categories of cut glassware, and for a cut candelabra and pedestal. The wall display also features one of the framed award certificates (also a reproduction) presented to all exhibitors ate the Fair; the accompanying medal designed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens is on display in a nearby case.

The award certificate, lithograph of the Libbey glass factory on the fairgrounds, and framed blue ribbons.

Also on display are examples of Libbey souvenirs from the Fair, including an amber-colored glass hatchet having an image of George Washington and a colorless glass paperweight. A copy of Kate Field’s The Drama of Glass (Libbey Glass Co., c.1895) in the case includes this passage:

Ever since the era of fairy tales the world has heard of glass slippers. Cinderella wore them and great was the romance thereof. But whoever before 1893 heard of a glass dress, and who conceived such a novel idea?

The most spectacular items in the exhibit are a glass dress bodice and parasol, part of an outfit that was the talk of the Fair when on display in 1893. Manufactured from spun glass woven into silk fiber, the dress and parasol at that time had a price tag of $2,500 (roughly $65,000 today).

Libbey made a glass dress for New York actress Georgia Cayvan. Although Cayvan reportedly wore her dress on stage, the gown was too fragile to be practical. Some sources report that Cayvan’s dress was returned to Libbey to be put on display on the Midway, while other sources (including the exhibit signage) indicate that a second dress was displayed in the Libbey Glass Works building.

The dress exhibited on the fairgrounds on June 10 caught the eye of the visiting Princess Eulalia of Spain when she toured the glass factory. Eulalia requested that Libbey manufacture another dress specially for her, which presumable was sent to Spain later that summer. While the fate of Eulalia’s dress is not known, the dress displayed on the Midway was called “Princess Eulalia’s” glass dress for the rest of the summer.

One of these glass dresses became the property of Florence Libbey Scott (wife of the company’s founder, Edward Drummond Libbey) who donated the dress and parasol to the TMA in 1925. The museum notes that “over the years the glass fibers have become brittle and broken into tiny shards. The shards in turn cut the silk, so that the weight of the fabric–particularly of the skirt–is too much for the remaining fibers to support.” Only the bodice of the dress is on display in the current exhibit. A spun-glass vest and neck tie, also from the 1893 Fair, are shown as well.

The display case includes two photographs of an unknown model wearing the full glass dress with parasol sometime circa the 1950s. The last time the dress was on display was in 1969, for the museum’s exhibition Libbey Glass: A Tradition of 150 Years. As the exhibit sign indicates, this dress truly was “the cutting edge of fashion” in 1893.

Celebrating Libbey Glass, 1818-2018 runs from May 4 through November 25, 2018, in the Glass Pavilion.

The bodice of Libbey’s famous glass dress.

The accompanying glass parasol.

[…] wife, Florence Scott Libbey, came into possession of Cayvan’s dress and parasol and eventually donated them to the TMA collection in 1925. The museum notes that the dress is in a fragile state as the broken […]

Who manufactured all the glass windows and iron for the buildings in the white city? There seems to be a very vague history of all the building works at this time. It would take a huge workforce to make, build such a fair.

It seems fire’s destroyed everything? All only reproductions of things now? Where did it all go? Weird really.

The Exposition employed thousands of workers to construct the temporary buildings for the 1893 Fair. Most buildings were subcontracted to other construction companies that sourced the needed materials. Buildings (even the mammoth exhibit halls) were primarily made of wood frame construction with some steel for supports then coated in “staff” (a mixture of plaster and jute fiber). Steel came from various sources. Most notable was the Ferris Wheel having components manufactured by the Detroit Bridge and Iron Works and the Keystone Bridge Company of Pittsburg and a massive axel made by Bethlehem Iron Company … all shipped to Chicago. Some steel from the original buildings was later salvaged and reused; one example of steel beam relics can be seen today in a park in Mount Vernon, Ohio! Glass was used mostly for skylights on rooftops; the resulting leakages caused Daniel Burnham to advise against this design for future fairs.

The erection of the buildings on the fairgrounds was thoroughly documented by many newspapers and magazines from the day the first stake was driven into the ground on December 5, 1890, until Opening Day on May 1, 1893. Thousands of photographs and illustrations show the fascinating progress. Also, the fairgrounds were open for the public to watch as buildings quickly rose in Jackson Park. The Exposition company was contractually required to return Jackson Park to its (mostly) pre-Fair state, so all buildings (but one) were either torn down, moved, or were destroyed by fire after the Fair closed.