Invocation by the Blind Chaplain

This is Part 5 of our series “Opening Day of the World’s Fair,” which explores the events of May 1, 1893, at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The full series can be found here.

At the conclusion of the performance of the “Columbian March” by the Exposition Orchestra, Director-General George R. Davis approached the front of the platform. He lifted his hand and commanded silence from the vast audience, to which there was instant obedience.

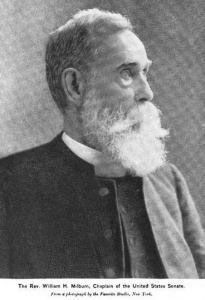

He said: “According to the official program for to-day’s exercises, I have the pleasure of introducing the Rev. W. H. Milburn, chaplain of the Senate of the United States, who will offer the invocation.”

The “Blind Chaplain” of the Senate

Reverend William Henry Milburn, known as the “Blind Chaplain,” served the United States House of Representatives in 1845 and for the Senate fifty years later, from 1893 until his death in 1903. During his long residence in Washington, the native Illinoisan was the intimate acquaintance of presidents, cabinet officials, senators, and congressmen.

Rev. Milburn rose from his seat at the right of the Duke of Veragua and advanced to the front of the rostrum, guided by a woman’s hand. She was Miss Louis (also recorded as Cora) Gemley, his adopted daughter who was his constant and faithful attendant for many years.

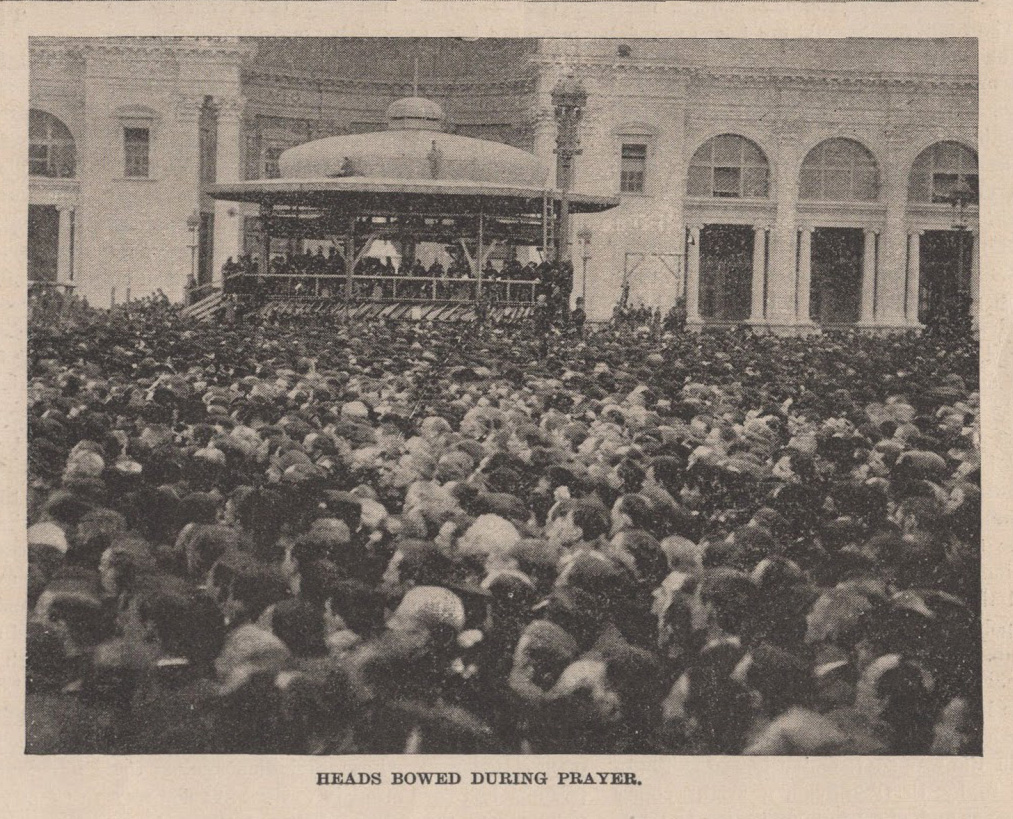

Facing the immense congregation, every head about him bowed and every hat removed. After a brief pause when the murmur of voices ceased, the blind chaplain uttered the opening prayer.

A blessing upon this great city, one of the wonders of the world

Standing before what he called the “imperial palaces” of the White City, the reverend asked for God’s blessing “upon this great city, itself one of the wonders of the world, whose site, within the memory of living man, was a pasture for wild beasts, the lair of the wolf and the nest of the rattlesnake, but which now sits enthroned as one of the capitals of the earth.” He asserted “man’s victory over air, earth, fire and flood” in the four hundred years since the landing of Christopher Columbus.

“Make this world’s fair a sabbatic year for the whole human race, a year of jubilee,” appealed Milburn while acknowledging “the heavy and grinding yoke of ill-paid labor” that built the fairgrounds.

Perhaps his most powerful words offered gratitude for the work of women—”shackles falling from her hands and estate, throbbing with the pulse of the new time, joyously treading the paths of larger freedom”—in building the Fair. Lauding “the grandeur of her self-sacrifice,” Milburn recognized “the inspiration of her genius, the product of her hand, brain and sensibility to shed a grace and loveliness upon the place, thus making of the house beautiful.”

As other religious leaders had done countless time before, Rev. Milburn prayed for “hastening the time when nations shall learn war no more, when the sword shall be beaten into the plowshare and the spear into the pruning-hook.” On the other side of the Grand Basin sat a 240,000-pound, 46-foot canon—the world’s largest gun—forewarning a different path for the nations of the world in the coming century.

The revered asked that the fairgoers be protected from “cholera, and every other pestilence,” which he attributed to God’s own “protests against filth, drunkenness, debauchery, and every kind of corruption.” There would be none of that in the White City.

The voice of the people is louder than the voice of God

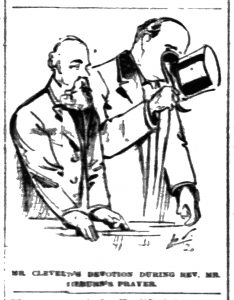

“Mr. Cleveland’s Devotion During Rev. Mr. Milburn’s Prayer” from the Chicago Herald, May 2, 1893.

A silence more eloquent than words followed the conclusion of the prayer. Of course, not all in attendance were Christians or people of faith. One reporter observed that, away out in the sea of human beings, a number of American Indians displayed their reverence by listening to the invocation with bowed heads.

Blessed with a strong voice and good presence, Chaplain Milburn’s prayer was audible enough to hold the multitude in respectful obeisance, claimed one report. Another countered that his voice was lost amid the storm of humanity, which continued with unabated force. As with all the speakers on the platform that day, the reverend was heard by few in the vast audience. A reporter from the Tribune cleverly wrote that “above his prayer sounds the voice of the people, and in the case the voice of the people is louder than the voice of God.”

Several news outlets complained that the chaplain’s invocation was too long. The Herald astutely pointed out that, when addressing the Senate, the reverend was limited to only three minutes for his prayers.

As Rev. Milburn returned to his seat, a Chicago woman approached the speakers’ stand. She was about to surpass the stately chaplain in the sheer volume of her recitation. A tornado started to swirl beneath her.

“Heads Bowed During Prayer” from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly, May 18, 1893.

SOURCES

(See our note about sources here.)

Dedicatory and Opening Ceremonies of the World’s Columbian Exposition. Stone, Kastler & Painter, 1893, p. 259.

“Epoch in History” Chicago Herald May 2, 1893, p. 1.

“‘Gath’ of the Fair” Chicago Daily Tribune May 2, 1893, p. 9.

“The Great Fair Open” San Saba (TX) News May 12, 1893, p.2.

“Opening Ceremonies World’s Columbian Exposition” in Columbian Exposition Dedication Ceremonies Memorial. Metropolitan Art Engraving & Publishing Company, 1893, pp. 212-224.

Pickett, Montgomery Breckinridge “Opening of the Great Fair” Harper’s Weekly May 13, 1893, p. 442.

“Ready for a World” Chicago Daily Tribune May 2, 1893, p. 1.

“Starting the Machinery” New York Tribune May 2, 1893, p. 11.

“Viewed from Above” Chicago Daily Tribune May 2, 1893, p. 5.

Leave A Comment