[Continued from Part 1]

A great stage decked with ambitious scenery

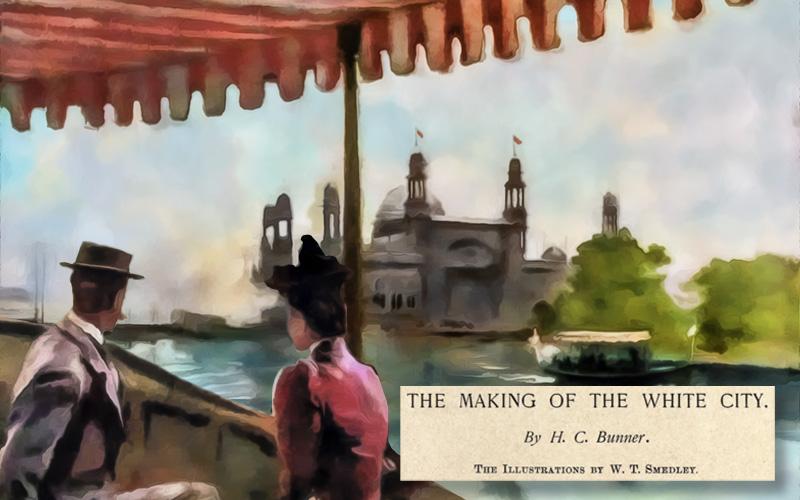

Perhaps the first thing that would strike a stranger entering the World’s Fair grounds in the summer of 1892 would be the silence of the place, the next the almost theatrical unreality of the impression by the sight of an assemblage of buildings so startlingly out of the common in size and form.

When I speak of the silence, I mean the effect of silence. There are seven thousand and odd men at work, and they are hammering and hauling and sawing and filing as noisily as any other workmen, but their noise is hardly noticeable among these vast spaces. The disproportion between the men and the structures is so great that this army of laborers looks like a mere random scattering of human beings. Insensibly the beholder gauges the amount of noise he expects by the size of the work before him and is surprised at the insignificant effect of what he does hear. All of this is part of that first impression unreality which I have spoken of as almost theatrical. I might call it positively theatrical if I could at the same time convey some sense of the effect of certain daylight views of a great stage decked with ambitious scenery. It is not only the grouping of the huge white and pale-yellow buildings that gives this impression, although it is hard enough to believe in that at first sight; for it cannot but suggest the extravagant fancy that a dozen or so palaces from distant lands—some unmistakably out of the Arabian Nights—have taken a sudden fancy to herd together. There are certain grotesque figures of the method of construction that strikingly heighten the general effect of strangeness. You watch two or three workmen moving apparently aimlessly upon the face of what seems a stupendous wall of marble. Suddenly a pillar as tall as a house rises in the air, dangling at the end of a thin rope of wire. The three little figures seize this monstrous showy shaft and set it in place as though it were a fencepost. Then a man with a hand-saw saws a yard or two off it, and you see that it is only a thin shell of stucco. As you adjust your perceptive faculties you see, two hundred feet above your head, the two halves of a large arch of veritable iron come together, moved by unseen engines, as noiselessly as though they were shadows against the sky.

“In the Process of Construction (and Entrance of the Hall of Mines)” by W. T. Smedley [Image from Scribner’s Magazine October, 1892 (Vol. 12, No. 4), pp. 399–418.]

“The whole thing is a sketch”

This is the first impression, and it is one that comes back most readily to the memory in after hours. But on the spot, it is shortly displaced by an amazed perception of the vast activity which informs the whole scene; and an unspeakable fascination seizes you as you watch the working out of a great fundamental idea.

“The whole thing is a sketch,” said one of its projectors; and in a certain sense it is a sketch, in lines of iron and wash of plaster. This is not an accident; it is the aspect, which, in the opinion of the builders of the fair, a group of buildings of this character should present. All, or almost all, of the structures must necessarily be temporary and removable or convertible to other uses. All must be of great size; all must be put up in a very limited space of time. This involves the adoption of the iron-frame system of construction, and practically makes elaborate internal decoration an impossibility. This situation has been frankly accepted by the architects. They have left it to the exhibits and their accessories to decorate the inside; their own task has been to make of walls and roofs a picture pleasing in general composition and harmonious in detail. An iron frame generally means an iron casing, but to carry out a scheme like this it was necessary to find some material less obdurate, more easily handled and more susceptible of artistic treatment. This material was found in a combination of plaster and jute fibre, called staff, which combines adaptability to all forms of plastic handling with a stiffness and toughness almost like wood. This stuff has made possible effects of construction which could never have been attempted under the same conditions with any other material. It is prepared as quickly as water and plaster and fibre can be mixed together; it may be made coarse or fine, rough or smooth in surface as may be desired; it may be cast or molded; it may be colored; and when it is dry and ready for use it is handled almost exactly like wood—bored, sawed, and nailed. This, then, is the wash in which the great sketch of the White City is executed. It takes every form that is necessary to clothe and ornament the iron skeletons; it suggests rather than simulates stone, and, considered for itself as a building material, it has certain agreeable qualities of brightness and softness.

“A Bit of Decoration” by W. T. Smedley shows building ornamentation made from staff. [Image from Scribner’s Magazine October, 1892 (Vol. 12, No. 4), pp. 399–418.]

Making construction an art by itself

It is of this material that all the mural decorations of the Fair Buildings are moulded, even to the statues, and it lends itself with equal readiness to embodying the graceful and somewhat stern classicism of Mr. Philip Martiny’s slim, long-winged goddesses, or the amazing and somewhat unaccountable vehemence of the strange allegorical family with which Mr. Karl Bitter is decorating the finials of the Administration Building.

There is a strong contrast between the clothing and the framework of the building. The iron and woodwork employed are of unusual strength; and the iron castings are in some instances wonders of scientific manufacture. For instance, in setting up the preposterously huge trusses of the main building it had not, up to June 1892, been found necessary to re-drill a single rivet-hole—which testifies to a miracle of constructive calculation at the distant foundries where these great masses of iron were shaped.

“Before the Agricultural Building” by W. T. Smedley shows Philip Martiny’s “slim, long-winged goddesses,” representing one of the signs of the Zodiac, that would ornament its roof. [Image from Scribner’s Magazine October, 1892 (Vol. 12, No. 4), pp. 399–418.]

A bold effect of harmony and balance

The whole business of construction has been reduced to a system original in many respects, and peculiarly applicable to the needs of the time and place, the main idea being to make of the construction an art by itself, leaving to the architect only the responsibility of artistic design. As Mr. Frank D. Millet, the right-hand man of Chief-Constructor Burnham, tersely puts it: “We give our constructors a picture and the dimensions, and say, ‘Make that!’” And even to Mr. Millet, who has helped in almost every World’s Fair for the last twenty years, this is a new step in the progress of architecture.

With this possibility of quickly and inexpensively modelling the exteriors of the buildings at will, it became also possible to the designers to attempt a bold effect of harmony and balance in the grouping of the structures, and to make the individuality of each building fit in with one underlying design which should at once appeal to the eye and to the memory, so that the thought of any part at once brings to mind its position and significance in the whole scheme. To some extent, of course, those features which they found themselves obliged to accept at the inception of their task have interfered with the carrying out of this plan in its absolute completeness; but the interference has been far less than might have been expected.

“The Administration Building” by W. T. Smedley [Image from Scribner’s Magazine October, 1892 (Vol. 12, No. 4), pp. 399–418.]

Impressive and symmetrical dignity and beauty

It may certainly be said that the least observant of visitors can hardly fail to grasp and retain some conception of the simple and effective ground-plan which unites this impressive collection of buildings, in the course of a single progress through the grounds. If he comes in by the main entrance, the idea of order and system is presented to him at the very outset. All the entering railroads converge here to a single perron, or platform, in front of which stands a square building, surmounted by a gilded dome. This is the Administration Building, designed by Richard M. Hunt, of New York. It is placed here to serve a double purpose, to form a vestibule to the Fair of impressive and symmetrical dignity and beauty, and to show the newcomer on his arrival the headquarters of control and management. Under this shining dome he passes to what may be called the grand court of the Exhibition, a mighty quadrangle, flanked on either side by towering white façades, and bounded at its farther end by a majestic peristyle raising its long array of columns against the clear background of an enclosed harbor. An artificial lake or basin of water occupies the greater part of this quadrangle, at its head stretching out into a long transept of canals, the northerly arm connecting with a long, irregularly-shaped lagoon at whose farthest end the pillared front of a classic temple rises from the water’s very edge. In the angle formed by these two water-vistas stands the mammoth among buildings, the Hall of Manufactures and Liberal Arts, stretching a third of a mile along the water-side.

It is the southwestern—or perhaps it would be more accurate to say the southern—corner of this stupendous pile that centres the whole ground plan and fixes in the mind the relation of its principal parts. The southern façade, covering the whole stretch from the canal to the lake, forms the most important boundary of the central plaza, while its longer frontage looks westward over canal and lagoon upon the broad park-land where lie, irregularly disposed, the buildings not included in the main group. Thus he who stands in front of this corner, at the point where canal and basin join, sees to his right and to his left the two essential divisions of the general design—the court scheme and the champaign scheme—and the thought must strike him that in their combination, in a proportion suggested on the one hand by the breadth and on the other by the length of the grounds, the possibilities of the site have been practically exhausted.

The “system of canals and channels navigable for pleasure-boats” included the Lagoon with its central Wooded Island. [Image from Hitchcock, Ripley The Art of the World Illustrated in the Paintings, Statuary, and Architecture of the World’s Columbian Exposition. D. Appleton, 1895.]

Wanders in graceful and natural curves

We must not forget the peculiar character of that site. Almost triangular in shape, it was, save for a few marshy hollows, as flat as a parade-ground. It lacked utterly the relief of rock or hill or woodland grove, or even of gracious slopes and terraces. The city lent it no architectural background. Whatever was to be done with it had to be done with the materials at hand. Under such conditions the best thing to be tried for was to make the landscape an attractive and appropriate setting for the buildings, whose size and importance could not but be exaggerated by the character of their surroundings. Here came in the idea of employing water as the effective feature of this setting, and in so broad and liberal a manner as not only to heighten the charm of the architect’s work, but to afford a positive novelty in stretching throughout the ground a system of canals and channels navigable for pleasure-boats—of making, in fact, a water-show in the very heart of the land-show. Through the greater part of the triangular plain the body of water created to this end wanders in graceful and natural curves, doubling on itself, stretching out in pleasant reaches, pushing an arm here, a hay there, sweeping around islands large and small; fringed its whole length in every bend and inlet with the simple and ever lovely flora of the inland water-side-iris, pond-lily, hellebore, sedge-grass, arrowhead, sweet flag, and bulrush-and set around with clustering thickets, and long lines of those lowly and grateful willows that ask only a plenteous draught of water to show their pearly gray-greens from the first stirring of the sap till the coming of the Fall.

“In the World’s Fair Grounds at Chicago—The Electric Building from the Lake” by W. T. Smedley [Image from Scribner’s Magazine October, 1892 (Vol. 12, No. 4), pp. 399–418.]

As it comes before the mighty front of the Main Building, this wandering stream is caught and held within bounds, until, submissively gliding amid the confines of artificiality, curved and arched and trimmed to line and angle, it plays its part in the great parade of the court square.

Despite its title, “Site for the Statue of the Republic” by W. T. Smedley shows the site where MacMonnies’ Columbian Fountain would be installed. The Agricultural Building is seen in the background. [Image from Scribner’s Magazine October, 1892 (Vol. 12, No. 4), pp. 399–418.]

The wonderful dress of electric light

The picture of which it forms a part—the picture of the great quadrangle—is one not easily forgotten, even when it is seen in the crude bareness of its unfinished line; when only the superb and well-balanced lines of the half-sheathed buildings bound its broad spaces and spread their long roof-lines against the cold sky. It will be more striking, perhaps, when it gets on its holiday drapery of flags and awnings, of splashing fountains and green parterres made gay with flowers; or seen at night, in the wonderful dress of electric light that is being woven for it, an astounding tracery of fire that is to outline every niche and corner and pillar, every balustrade and terrace-edge, down to the water-line, where a triplicate row of lights, mirrored in the shining depths, will map out the margin of the basin; while from time to time the startling, all-revealing glare of the lake-side search-lights travels across the whole enclosure—the bull’s-eye lantern of our familiar electrical giant.

The “candid classicism” of McKim, Mead & White’s Agricultural Building was best seen “across the water; in an unbroken perspective against the clearest quarter of the sky.” [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

The calm beauty of its graceful detail

And yet, fine as is, the theatre it presents for splendid pageantry of this sort, to those who have seen it in the last stage of its growth the trappings may only cost the great square something of the simple dignity it derives from the architectural strength and just proportions of the buildings which wall it in. Properly speaking, the whole space is one broad avenue from the railroad terminus to the Lake, for two-thirds of its length practically a water-way, with the Administration Building planted squarely midway of the remaining third; but to view it from a point in the water-way is inevitably to pick out three buildings as salient boundaries—the main building, known as the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, the Administration Building, and the Agricultural Hall. In the first case it is pre-eminently the aggressive size that attracts the eye, in the second it is the application of a striking form to a peculiarly appropriate situation; in the third what captivates the attention is simply the charm of a beautiful design ideally well displayed. Seen, as it must first be seen, across the water; in an unbroken perspective against the clearest quarter of the sky, so disposed as to be free from the dwarfing influences of any other building or group of buildings, its candid classicism receives every advantage that situation can give it, and the eye turns from the effect of breadth and mass in the main building opposite to the calm beauty of its graceful detail with a sense of grateful and natural transition, recognizing a certain complementary relation between the different kinds of dignity expressed in the huge structures.

“Near the Hall of Mines.—The Great Arches of the Main Building (Hall of Manufactures) in the Distance” by W. T. Smedley. Telephone poles and lines running through this scene (and others) were removed from Jackson Park before the Fair opened in May 1893. [Image from Scribner’s Magazine October, 1892 (Vol. 12, No. 4), pp. 399–418.]

An ample diversity of thought and treatment

But if these three buildings offer the most characteristic and unforgettable façades of the square, it is not to be supposed that the rest of the group of giants fail in effectiveness or adequacy in the matter of external appearance. On the contrary, they carry out admirably the idea of restriction to healthy classical lines, which, by mutual consent, has governed the designers of the whole group; while they offer, individually, an ample diversity of thought and treatment. But their position, at the inland end of the court, presenting their main entrances to the Administration Building, has been governed in some measure by the exigencies of their use.

On the southerly side stands, with its annex, the Machinery Hall, designed by Messrs. Peabody & Stearns of Boston, covering in all a space of ground some fourteen hundred by five hundred feet. On the northerly side are the Hall of Mines and Mining, and the Electrical Building, so called; buildings almost twins in size (about seven hundred by three hundred and fifty feet each), but sharply differing in design-the Hall of Mines, with its massiveness of design and detail, and the Palace of Electricity, raising on high its almost fantastically broken skyline. The one is the work of Mr. S. S. Beman, the other of Messrs. Van Brunt & Howe, of Kansas City. Outside of these, or rather, around the comer from them is the Transportation Building, a vast hall running nearly five hundred feet each way from the imposing Roman arch, with its florid half-oriental decoration, which forms its main entrance. This edifice stands as a sort of connecting link between the serried ranks of the quadrangle buildings, and those which are ranged in “open order” around the water space, in the middle of the champaign or park-like portion of the grounds. These are, in the order of their position: The Horticultural Hall, the Women’s [sic] Pavilion, the Illinois State Building, the permanent Building of the Institute of Art* (around and beyond which are the smaller headquarters of the various States and foreign nations), and then, returning on the lakeward side of the lagoon, the Fisheries Building and the United States Government Exhibition Quarters, which comprise a large building, and at the lakeshore an enclosed harbor for the naval exhibit. Here the long ellipse reaches the northerly end of the main building, and thus connects with the base of construction formed by the great court, and that coign of vantage at the confluence of basin and canal from which the eye first takes in the whole broad and varied scheme.

* Note: The “permanent” building of the Art Institute of Chicago was built in downtown Chicago to house the World’s Auxiliary Congress in 1893 before being converted into the current art museum at the end of the Exposition.

“Lunch Time” by W. T. Smedley depicts a vista from the front of the Palace of Fine Arts looking south across the North Pond, with (left to right) the Fisheries Building, U.S. Government Building, arches of the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, and the edge of the Illinois State Building. [Image from Scribner’s Magazine October, 1892 (Vol. 12, No. 4), pp. 399–418.]

It is from this point that a comprehensive view must be taken of the arrangement as a whole, and of the harmony or discordance of its several parts. Of the quadrangle it may be said that from the layman’s point of view criticism would be hypercriticism. Whatever individual taste or scholarship may find to question or reject in the details of this marvellous plaza, with its thronging façades, its spacious waterways, its treasures of columns and fountains; the people who go out to see a great and beautiful sight would be mean and ungracious if they sought to weaken by ungenerous analysis the satisfying impression of grandeur and beauty, and of eminent fitness and good taste, produced by the whole picture. It is a noble design, broadly conceived, and carried out with an amazing amount of patient skill and conscientious thought.

To turn to the other and longer vista of the water parkway is to see how sadly the interference of lower standards can mar the complete execution of an exquisite, artistic design. For almost a mile the eye travels the delightfully diversified length of the beautiful waterway which Messrs. Olmsted & Codman have laid out, to rest at last upon the almost sacredly classic front of the great Art Building, calm and pure in its beauty as the waters of the lake from which it rises. It is a beauty of line and proportion rather than of decoration, a beauty of balance and modulation, a beauty which must be seen in its completeness, undisturbed by any other spectacle, if you would feel the full delight of its serenity. And right here, across full half of the western end, the Illinois State Building thrusts an unseemly and ill-bred shoulder into the view, like a dry-goods emporium affronting a Greek temple.

Henry Ives Cobb’s Fish and Fisheries Building. [Image from The Graphic History of the Fair. Graphic Co., 1894.]

Joyousness is the keynote

There is another building in the way on the eastern side, but it neither affronts nor offends. This is the Fisheries Building, designed by Mr. Henry Ives Cobb, and its delicate pavilions, with their clean, significant lines, and their airy, skyward lift, take gracefully a subordinate part in the picture and relieve a severity with which they are in no wise out of keeping. Joyousness is the keynote of Mr. Cobb’s design; his is a happy concept for a people’s summer pleasure-house, and he permits himself something like an approach to architectural humor in his grotesque decorations of conventionalized forms of fishes and crustaceans. It may be objected that the primary purpose of the building is scientific, but to this it should be urged that ichthyology is a science which it is hard to disconnect from a certain fantastic curiosity, and that, in spite of what the learned have said, the humor-loving human being will never take fish quite seriously—and moreover, that the man who conceives a design so wholly delightful in spirit as Mr. Cobb’s, need make no more apology for the lightsomeness of his art than he does for the gracefulness of it.

Across a lake from the Fisheries Building is the Building of the United States Government, which promise to be one of the most valuable and important exhibits in the whole Fair. It ought to illuminate the soul of even a Congressman from Darkest Kansas with new lights on the selection and compensation of government architects.

Bunner wonders how Louis Sullivan’s Transportation Building “could have gone so far as it has without developing more positive evidence of bad taste or lack of skill.” [Image from Report of the Board of General Managers of the Exhibit of the State of New York at the World’s Columbian Exposition. James B. Lyon, 1894.]

On a lower plane than others

The Horticultural Hall, which is the largest building of the park group, is sufficiently imposing in point of size, but disappointing in its heavy and earthbound lines, the ponderous effect of which is accented by the unnecessarily broad frieze which swathes the building like a wide bandage. It is, however, only fair to say for Mr. Jenny’s [sic] building that considerations of interior effect have had more weight than in the case of any other edifice (except, perhaps, the Administration Building); his highly colored courts being made a characteristic feature.

It is impossible to avoid speaking of certain unsatisfactory points in this part of the exhibition—impossible because the very high standard of achievement established elsewhere provokes the uncomplimentary comparison. Yet it must not be forgotten that such criticism is, after all, only comparative. It is mainly because so much has been done thoroughly well, that the element of dissatisfaction seems unduly irritant. To use the consoling axiom of Charles Reade’s humble publicist, “Where there’s a multitude, there’s a mixture;” and it was inevitable that in a work so vast some parts should be on a lower plane than others, both in conception and execution. The thing to be wondered at is that this undertaking could have gone so far as it has without developing more positive evidence of bad taste or lack of skill. Every World’s Fair, I suppose, must have its “Iolanthe in Butter,” and perhaps Iolanthe has her place in the art-education of a people. If she has, it may be incidentally remarked that ample provision has been made for filling her place in this instance. There is a modern and realistic rilievo at the base of the great entrance of the Transportation Building, which does the completest justice to the Pullman-car end of our civilization.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

“Model for Statue of the Republic by Daniel C. French” by W. T. Smedley. The completed statue was not yet on display in the summer of 1892 when Bunner visited the fairgrounds. [Image from Scribner’s Magazine October, 1892 (Vol. 12, No. 4), pp. 399–418.]

It has been difficult to convey the effect of what has been done: it would be impossible to convey the effect of the doing of it. It is a great exhibition in itself—the concentration of human energy and intelligence which has made this work possible. The men who are doing it are gathered together from distant cities, and for the months or years that their task may require of them, they have given themselves up as absolutely as soldiers give themselves to their duty. It is, in fact, an army of laborers with a staff of artists and architects that is under the command of Mr. D. H. Burnham, the Chief of Construction, a man born for generalship, strong in executive ability and in the capacity for inspiring loyalty and devotion. It is through his constructive and executive genius that the admirably able corps of architects and designers gathered together at Chicago are enabled to realize their splendid fancies in all the strength of their ambition. Within the walls of the great enclosure these men lead, for months at a time, the life of military officers in the conduct of a campaign, living in barracks, their days’ work beginning with their waking and ending only with too long deferred sleep.

They have worked so hard and so long together, at home and on this sandy plain, that, like all old comrades of war, they have a talk of their own, and among themselves they sometimes speak of a certain “microbe,” the germ of something which, with soldierlike levity, they figure as a disease—the enthusiasm—the uncontrollable, action-impelling enthusiasm for their great enterprise which sustains them through this long strain on body and mind; the enthusiasm which seizes upon all who watch them at their grand toil, and which I wish were mine to communicate in telling of what they are doing.

“Going Home from Work” by W. T. Smedley depicts a few of the thousands of workers—mostly immigrant laborers—who built the buildings and grounds of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. [Image from Scribner’s Magazine October, 1892 (Vol. 12, No. 4), pp. 399–418.]