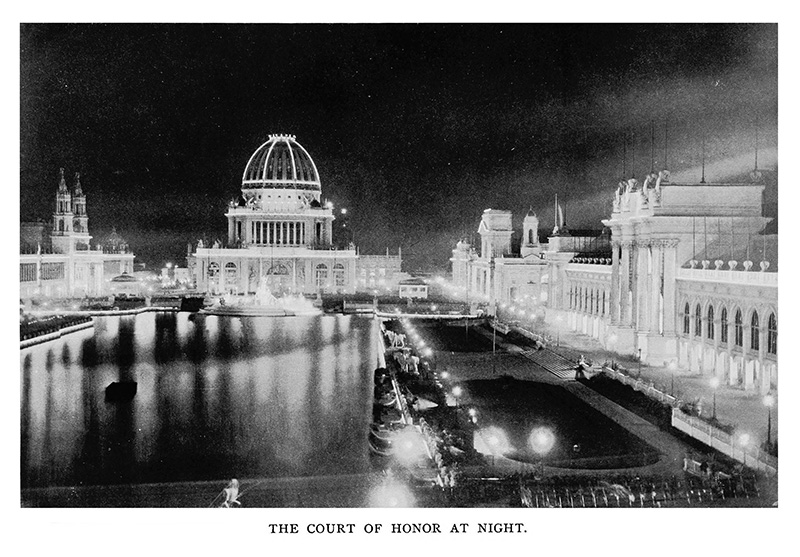

“However grand, complete and astonishing the World’s Fair may appear to the public by daylight, it is at night that it can be seen in all its splendor and magnificence,” wrote the World’s Columbian Exposition Illustrated [read the article here]. Another description of the nightly illumination of the Court of Honor comes from the newspaper story reprinted below, originally from an (unknown) Chicago newspaper.

Turning Day into Night

“After dark at the World’s Fair will be one of the things that scribes and chroniclers will never be tired of describing. When even the garish splendor of the transportation building softens into beauty under the pale beams of the moon, and all the staff is marble and all the tinsel gold, then the grand basin, the heart and center of the fair, will be a sight for wonder-satiated visitors to fall into new raptures over.

Photograph of the Court of Honor at night. [Image from Johnson, Rossiter A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Held in Chicago in 1893. (D. Appleton and Co., 1897).]

As usual with all things at the fair, the effect will be something unequalled before, and in some respects it will be quite new. It will be something that has been dreamed of, but never attempted—the decoration of a large area by the light of thousands of tiny incandescent lamps.

The decorative effects of rows and clusters of incandescent lamps were made known to Chicagoans on a very miniature scale during dedication week, when hundreds journeyed to Michigan Avenue to see the Auditorium’s triumphal arch, or gazed at the rival displays on the corner of Dearborn and Madison streets. Multiply such displays by the thousands, stretch the beaded lines of light along the topmost corner of every building facing the grand basin at Jackson Park, add the changing colors of the fountains nine times as imposing as Mr. Yerkes’s,[1] and a vision of the heart of the fair after dark can be faintly imagined. If the lighting of the fair does not rank hereafter as the ninth wonder of the world, its architects will be greatly disappointed.

The “triumphal arch” of Louis Sullivan’s Auditorium theater stage, as it looked in 2017. [Photo by worldsfairchicago1893.com]

The treatment of the colonnade in machinery hall will be the same, only the soft glow of the lamps will be seen in the loggia lighting up the painted walls and the gilded capitals of the columns.

The nighttime illumination of the MacMonnies’ Fountain with Machinery Hall in the background. [Image from McIntosh Battery and Optical Co. glass slide.]

Night view of the electric lights in the Court of Honor by an unknown photographer (cropped). [Image from the Kenneth M. Swezey Papers, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.]

Above the dome of the agricultural building Diana’s statue is placed on a golden ball in a shallow, cup-like depression. Under the inside rim of the cup will be a hidden row of incandescent lamps, the light from which will illuminate the form of the goddess without betraying its origin. Many a visitor will find himself wondering how that matchless form is bathed in light.

“The Court of Honor by Moonlight” depicts a search light from the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, exhibition palaces outlined with light bulbs, and the golden Diana sculpture atop the Agricultural Building. [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair (W. B. Conkey, 1894).]

A tinted lantern slide showing the electric fountain in front of the Administration Building at night. [Image from the Brooklyn Museum, Goodyear Archival Collection.]

Engineer James A. Lounsbury [2], who has charge of the incandescent lighting of the fair, estimates the number of lamps required for the illumination of the basin at 12,000.

“It is a big scheme of decoration,” said he, in speaking of the matter today, “but one which the exposition will carry through successfully. The main idea running through it is to make the light subservient to the architecture, bringing out the works of the builders without making the source of light too prominent. It will, we believe, be something for visiting electricians to study as well as admire.”

The Grand Court at Night. [Image from Harper’s Weekly, June 24, 1893.]

NOTES

[1] Mr. Charles T. Yerkes, the “street car millionaire,” presented to the people of Chicago a great electric fountain in Lincoln Park. The nightly display of colored lights attracted many visitors during the 1893 World’s Fair.

[2] James A. Lounsbury, who worked as an electrical engineer in the Mechanical and Electrical Department of the Exposition, was from Hartford, Connecticut.

SOURCE

“Turning Day into Night” Hartford (CT) Courant p. 2.