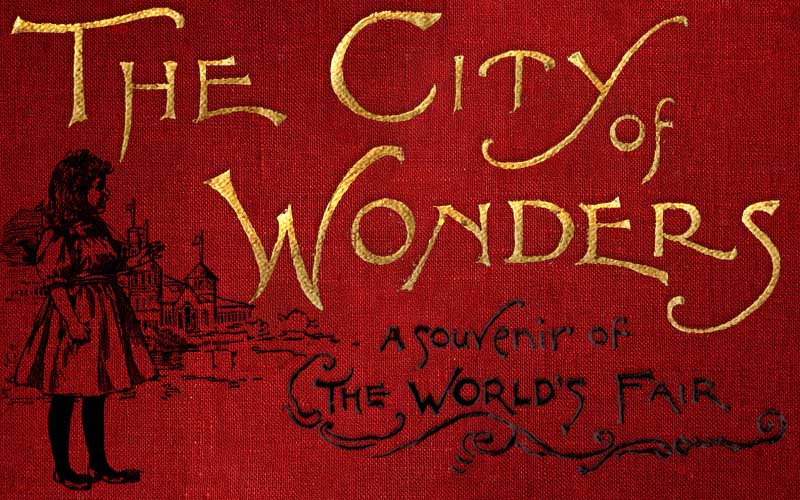

THE CITY OF WONDERS

A Souvenir of the World’s Fair.

BY

MARY CATHERINE CROWLEY

CHAPTER 8. THE LIBERTY AND COLUMBIAN BELLS, ART GALLERIES, ETC.

[For other installments of our serialization of The City of Wonders (1894), see the Table of Contents]

A view of the state buildings on the north grounds of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894.]

The Pennsylvania Building, designed by Thomas P. Lonsdale of Philadelphia to reproduce Independence Hall in Philadelphia. [Image from Shepp, James W.; Shepp, Daniel B. Shepp’s World’s Fair Photographed. Globe Bible Publishing, 1893.]

“There it is, wreathed with laurels and guarded as one of the nation’s most precious treasures!” exclaimed Ellen.

“Yes,” said Uncle Jack. “The grand old bell which rang out the glad tidings that the Continental Congress had declared the colonies free and independent states, and announced the dawn of a new era; a government ‘of the people, for the people and by the people’; the old bell that, one would think, felt in its soul of bronze the mighty and responsive thrill which ran through the country at the bold act of its representatives; the clarion voice which proclaimed the sentiments of that great assembly;–the voice now proud, dauntless and exultant; again defiant, stern or tremulous with emotion; and then, with a clang like an inarticulate cry, becoming mute forever, as the noble heart of the bell broke for very joy.”

The Liberty Bell on display in the Pennsylvania Building. [Image from Graham, Charles S. The World’s Fair in Water Colors. Mast, Crowell & Kirkpatrick, 1893.]

“How strange that the old bell should have cracked on that occasion!” said Nora.

“As if,” interposed Ellen, “having had the honor of telling such grand news, it was determined never to utter commonplaces again.”

“Well, it is a regular old hero, anyhow,” said Aleck. “See the inscription around the rim. It is like the commission of a commander-in-chief conferred upon this veteran leader of all the bells of the country.”

They drew nearer and read engraved upon it the words of the spirited order of the patriots: “Proclaim Liberty throughout all the land, unto all the inhabitants thereof.”

The Columbian Liberty Bell. [Image from Buel, J. W. The Magic City (Historical Publishing Company, 1894).]

“That fine bell, cast to commemorate this magnificent Exposition and the achievements of Columbus, has not yet reached the World’s Fair,” responded Mr. Barrett.[1] “Its journey from the foundry has been like a triumphal progress, since every city along the route has claimed the right to pay it public homage as the symbol of the glories of the Admiral of the Ocean Seas, and of the greatness of the Republic which is in itself a sublime result of his success. The metal for this bell was, you know, contributed by the citizens of the United States. Men, women and children from all parts of the country sacrificed their most precious souvenirs and heirlooms to furnish the amount of silver necessary. It represents, therefore, the noble emotions of the American people. On the Fourth of July of this the Columbian year, its first tones rang grandly and gladly, calling upon all the world to rejoice with us in the fulfilment of the promise of freedom which the voice of the old Liberty Bell proclaimed. Let us hope and pray that here, in this White City of Columbus, it may ring in another epoch for our land, not alone of material prosperity, but of true standards and high principles among rulers and people; since nations, like individuals, retrograde unless their aim is ever onward and upward.”

In this building they saw many lesser relics as well, among them the table upon which the Declaration was signed. They also paid particular attention to a picture representing the making of the first American flag.

Uncle Jack related the story there portrayed, telling how one day, in the year 1777, Betsy Ross, a worthy needlewoman, who kept a humble shop on Arch Street, was waited upon by a committee appointed by Congress, of which General Washington was chairman; how, having received minute instructions in regard to the design decided upon, she fashioned the banner as directed, submitted it to the committee, and had the honor of seeing her handiwork floating in the breeze above the tower of Independence Hall, as the flag of the new nation,–the Stars and Stripes, the symbol of freedom, prosperity and happiness the world over.

The Florida Building, designed by W. Mead Nalter of Chicago to reproduce Fort Marion in Saint Augustine. [Image from Shepp, James W.; Shepp, Daniel B. Shepp’s World’s Fair Photographed. Globe Bible Publishing, 1893.]

As the party emerged into the open air once more, Nora said, glancing down the avenue:

“Oh, there is the picturesque Florida Building, which was modelled after the ancient fort at St. Augustine! Nell and I peeped into it yesterday, Aleck, while you and Uncle Jack were talking to a guard. The interior is all hung with lovely grey Southern moss.”

They turned their steps in another direction, however, and presently entered the Massachusetts Building.

The Massachusetts Building, designed by Peabody & Stearns of Boston as a reproduction of the historic residence of John Hancock on Beacon Hill in Boston. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

Nora stopped suddenly, attracted by an ancient gazette which hung in a frame upon the wall.

“This is a singular coincidence!” she cried. “We have just seen the Liberty Bell, and now almost the first thing I meet with here is this old newspaper, which contains a notice of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence.”

The others gathered around her to scrutinize the curious, unpretending sheet, so great a contrast to the voluminous “dailies” of the present.

“The Philadelphia Packet, Monday, July 8,” she began, reading the title and date, and then the heading of the article that described the doings of the Congress,–an article which must indeed have had a startling effect upon the subscribers. “Think of it! This is the first printed account of that great event.”

“True,” returned her uncle. “This little newspaper must have been printed on a hand-press just after the proclamation of the independence of the colonies, and no doubt brought the first news of it to many people living at a distance from the Quaker City, which was the seat of government in those days.”

“What a lucky chap the reporter was who first got hold of the Declaration of Independence as a piece of news!” Aleck rattled on. “Next to being one of the Signers, I should like to have been that fellow, or else the printer who first put it into type.”

Ellen now summoned them to examine two quaint pictures, saying:

“These are labelled ‘original engravings by Paul Revere.’ Does it not seem odd to think of the hero of Lexington and Concord as working at a trade?”

“I suppose you fancied he did nothing but ride to

‘Spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country-folk to be up and to arm,’”[2] retorted her brother teasingly, although indeed he could not have told anything about the bold patriot beyond the tale of the famous ride.

“Paul Revere undoubtedly earned his living as an engraver, notwithstanding that he is known to posterity generally-only as the gallant horseman,” said Mr. Barrett.

This building was particularly rich in souvenirs of colonial times, and the girls flitted from one to the other, chattering gaily.

“Look at this old cradle used by five generations of the Adams family, including the two Presidents,” observed Nora.

“Here’s a baby’s christening robe two hundred years old,” added Ellen. “And see these gowns of heavy brocade which were worn at dinners given to Washington.”

“I’ve found a shovel used for passing coals for lighting the pipes of the worthies of Boston town,” announced Uncle Jack. “And here is a pottery dish divided in the centre, one section being used for hasty-pudding and the other for baked beans. Those were evidently not the days of course dinners.”

Then there were spinning-wheels, antique chairs, tables and writing-desks used by distinguished personages, and all sorts of odds and ends; in fact, the place was a charming old curiosity shop.

The south side entrance to the Palace of Fine Arts. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“Probably you will never again see so many fine modern paintings together as are included within these walls,” said Mr. Barrett.

He pointed out the masterpieces of the French, English, Italian, Spanish and American collections and paid particular attention to the Russian pictures, as well as those from Denmark, Norway and Sweden,–schools of art distinctive in themselves, and unlike any with which we are familiar.

Augusto Corelli’s oil painting “The Angelus on St. Peter’s Day” (Roman Harvest) on display in the Italian section of the Palace of Fine Arts. [Image from Illustrations Art Gallery of the World’s Columbian Exposition (Barrie, 1893).]

“It is hardly like a picture at all,” said Ellen. “One seems to be in the midst of those harvest fields, and surrounded by that golden sunset light which shines upon the men and women reapers. There is the grand dome of St. Peter’s great Cathedral in the distance; and one can almost hear the bells of Rome ringing the evening Angelus, at the first tones of which the workers have ceased their toil and bowed their heads in prayer.”

Uncle Jack decided that the party were in duty bound to visit the Illinois Building. They found it one of the finest on the grounds.[4]

The Forestry Building, designed by Charles B. Atwood. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“They are contributed by the different states and by foreign countries, each furnishing specimens of its native growths. The roof is thatched with bark, and the interior finished in various woods in a way to show their beautiful graining and susceptibility to polish.”

The massive Krupp gun, designed by Charles B. Atwood. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“I never imagined there could be such great cannon,” he cried. “Why, the machinery required to operate each occupies the space of a good-sized house; and it seems as if a missile from anyone of them could sweep almost every living creature from the face of the earth.”

“At least one such gun has been found an invincible guardian of an entire coast,” answered Uncle Jack.

“Ho-ho! look at that cyclops over there! All the other giants appear like pigmies beside it!” continued the boy, with masculine admiration of the mighty power and strength which endow these terrible engines of destruction with an element of sublimity.

“That is the largest cannon ever cast,” was the reply. “Its weight reaches the enormous figure of 124 tons, and the cost of manufacture was $50,000. Its length is 87 feet and the bore 25 inches; the projectile used weighs 2,300 pounds; $1,250 is the expense of a single discharge. Herr Krupp, the celebrated maker, has signified his intention of presenting this mammoth gun to the United States for the defense of the port of Chicago.”

“These monsters are a thousand times more frightful than the fiery dragons of old,” said Nora.

“They must have the effect of bringing all wars to a speedy end, at any rate” sighed Ellen, feeling the necessity of viewing them in some extenuating light, since otherwise it would be too dreadful to know that there were such objects formed to be the emissaries of desolation and death.

Machinery Hall (also called the Palace of Mechanic Arts), designed by Peabody & Stearns of Boston and seen from the South Canal. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

The central aisle of Machinery Hall. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

“Every revolution of the machinery is a tribute to the genius of the inventor.”

“This machine seems almost to have a mind of its own, and uncommon sense too,” said Nora. “How the little spools march into place of themselves, with the regularity and precision of soldiers! And when each has been furnished with its share of cotton, a pretty shining scissors pops up like a fairy and snips the thread just at the proper time–“

“Quite like Atropos, one of the Fates supposed in the old mythologies to perform that office for mankind,” interrupted Mr. Barrett, laughing.

“And then the clever spools step down and out, to make room for others,” added Aleck; “and are imprisoned in boxes, where they have to stay until set free by purchasers.”

“But turn down this cross aisle. I want to show you the machinery for the transformation of the wool, as it comes off the sheep’s back, into yarns and worsteds; and the knitting-machine, where one row of needles sweeps around over another as quick as a wink, and the fabric grows as if by magic. You might fancy it a giantess of domestic tastes knitting stockings.”

[In Chapter 9 of The City of Wonders, the Kendricks will delight in the living attractions of the Fisheries Building.]

NOTES

[1] “That fine bell … has not yet reached the World’s Fair” The Columbian Bell (the “New Liberty Bell”) was forged in Troy, New York, and arrived by train on the fairgrounds on September 2, 1893. It was on display on the west side of the Administration Building.

[2] “Spread the alarm” is a passage from “Paul Revere’s Ride” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

[3] “The Ave Maria upon the Roman Campagna on St. Peter’s Day” Augusto Corelli’s oil painting “The Angelus on St. Peter’s Day” (Roman Harvest) hung in the Italian section. In Art & Architecture Vol. II The Art (George Barrie, 1893), William Walton describes the canvas: “His immense canvas, peasants pausing in their labors on the Campagna at the sound of the Angelus on St. Peter’s Day, the ruins of a great aqueduct in the background, is an older picture, frequently exhibited, but not interesting in proportion to its size and the labor bestowed upon it.”

[4] That would make them near alone in this opinion of the W. W. Boyington design of the host state’s headquarters, which architectural reviewers almost universally panned.

[5] “The Forestry Building next claimed their attention.” This is quite a long way from the Illinois Building! Perhaps the party again rode the Intramural Railway, which they could have picked up next to the Woman’s Building and been let off at the South Loop station near the Krupp Pavilion.