A visit to the 1893 World’s Fair inspired Penelope Gleason Knapp to pen a romantic and effusive love letter to the wonders of the White City. With Victorian flourish, she describes her rapturous experience in the Court of Honor, “where enchantment reigns supreme.” Her memoir offers a reminder that electric illumination on such a grand scale was an overwhelming experience for many visitors from small towns in America.

Penelope Gleason Knapp

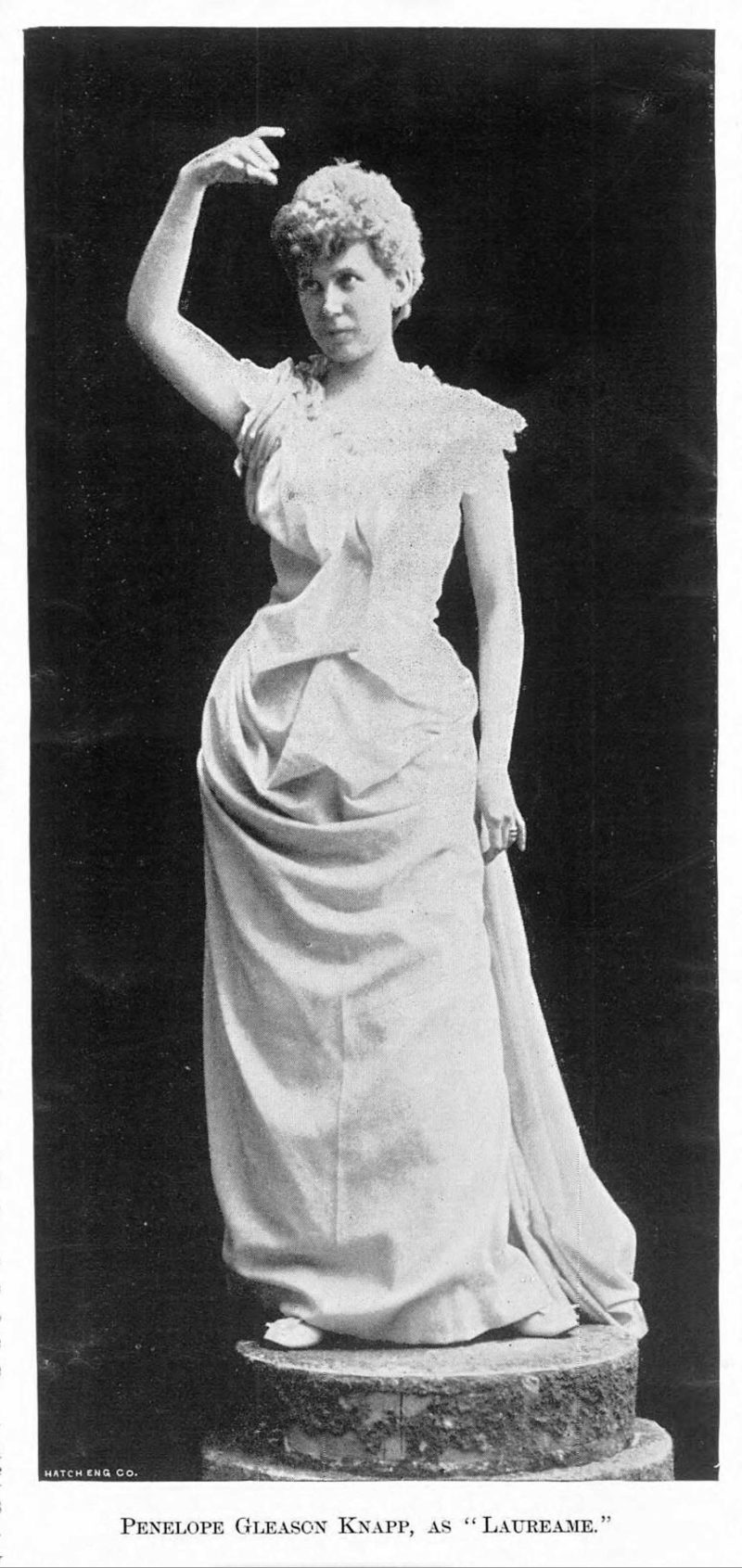

In 1893, twenty-two-year-old Penelope Gleason Knapp was living in Albion, Michigan, where she worked as a teacher of elocution and dramatic arts. At an early age she had showed an interest in the stage while living on Lake Keuka in Upstate New York. She returned there in 1891 to perform one of her specialty “costume recitals” and offered similar musical and literary entertainment in Albion in April 1893. A puff piece at that time described the aspiring actress as “tall, slender and dignified, decidedly inclined to the brunette type … [with] an intelligent, discriminating conception of the character she depicts” and offered the grand claim that Knapp “is acknowledged to be one of the best dramatic readers and amateur actresses in the West.” (The West, it seems, was unavailable to confirm or deny the claim.)

Penelope Gleeson Knapp in 1893. [Image from Werner’s Magazine May 1893.]

She was still a young and undeveloped author when the Chicago Inter Ocean newspaper ran “The Court of Honor,” her grandiloquent account of a night at the World’s Fair reprinted below, in their October 4, 1893, issue.

After the Fair

By 1897, Knapp was living in Rochester, New York, and a report two years later noted that she had “abandoned teaching and has taken up the pen.” She wrote a novel titled Red Flames and White Ashes in 1899, but it does not appear to have been published.

By 1910, Knapp was living on the northside of Chicago where she listed her profession as author but also was running a business in “physical culture” from an office in the Auditorium Building downtown. She researched and wrote articles on an interesting range of topics, including travel pieces for Outdoor Life, a profile of aviator Glenn H. Curtiss (“Where Flying Machines Are Made”) in The Progress Magazine, a feature on the Roycrofters campus in the Chicago Tribune, and series of what today would be called “self-help” advice and wellness pieces.

Chicago at the time was the capital of film-making, before the industry settled in Hollywood. Knapp began writing scenarios for motion pictures and by 1915 was the head of the Knapp Photoplay Right Company. She also wrote the screenplay for The Victory of Virtue (1915), which screened in Chicago on September 9, 1915.

Knapp’s unpublished novel Marcene was adapted for the silent screen as The Broken Butterfly, produced as a 1919 drama. This may be her only work for the screen that has survived. The film was restored in 2019 with a celebration screening in Hollywood.

She reportedly also authored photo-plays titled The Mystery of the Sacred Dagger, Echoes, Ashes and Roses, Four Leaf Clover, The Wilds of Nanaung, The Heritage of Blood, and The Cross of Life, but these appear to be either unproduced or released under different titles.

After spending about four years in New York City writing for a beauty magazine, Knapp returned once again to Chicago, where she died on October 11, 1924. The body of Penelope Gleason Knapp was buried in Hammondsport, New York.

THE COURT OF HONOR.

“Have Your Eyes Beheld the Glories?”

SCENE OF ENCHANTMENT.

The Going of the Day and the Coming of the Night in Gleaming Radiance.

Have you sat in the Court of Honor and watched the twilight gather in a hazy mist over Lake Michigan’s broad expanse of shimmering blue? Have you watched the uncanny shadows blending strangely with the last flickering sunbeams, then thicken over the waters and creep like messengers of evil along the wave-lashed shore, and up the grand canal, till all was enveloped in a garb of somber black? Have you closed your weary eyes for one brief instant upon the weird darkness which always brings with it gloom, and then opened them suddenly to find yourself transported, lifted bodily as it were, into a land of celestial beauty, where millions and millions of gold and silver lights flash rhythmic, glittering purity all about you? Where enchantment reigns supreme? Where your heart thumps violently, and your breath comes in short, quick gasps, and then seems to stop altogether?

If you have sat in the Court of Honor about which is built the White City and experienced these emotions then you have both witnessed and realized the grandest transformation scene on earth, which, for want of a better name, we will call From Hades to Heaven. Ah! we whisper softly as this dream of mystic splendor unfolds before us, “We must be in heaven—yes, in heaven.” Then we rub our eyes and pinch ourselves to make sure we are not in a trance; vaguely we wonder how we climbed the “Golden Stair” without any conscious effort on our own part. We have reached the goal, but how utterly unworthy we feel to accept the honor thus thrust upon us. However that sensation soon passes; we are in the supernal land and must enjoy it to the full extent.

The Court of Honor by Moonlight. [Image from Picturesque World’s Fair. W.B. Conkey, 1894.]

Light and Glory

Our wildest fancy never painted anything so truly wonderful. We are fascinated, we are stupefied at the stupendous combination of light and glory. It seems a visible supermundane spectacle from an invisible source. Our first intelligent glance rests upon the triumphal glittering dome of the Administration building, with its rows and clusters of flashing, shining, shimmering, winking, blinking, drazzling lights. Surely, we think, that must be the Golden throne. In imagination we see myriads and myriads of white winged angels floating through space, and hear harmonious, dreamy music, soft and sweet as the sighing of an Aeolian harp. How we wish that we were all alone in this Eden of glory. We feel annoyed if any one near us speaks above a whisper. A rippling, mirth-provoked laugh jars upon our nerves. It seems so entirely out of place—so sacreligious [sic]. Unconsciously the selfish element in our nature holds for the time full sway. We long for perfect silence. The deep, deep unbroken silence which alone can pay fitting tribute to the glittering tiara of fairy-like beauty which crowns with jeweled splendor this glorious, magic court. Words, flippant, idle words seem void of expression and wholly inadequate to do it passing justice.

Flash! flash! A streak of light glides by us. We draw our fascinated gaze slowly and reluctantly away from the golden dome and let it follow in a dreamy sort of way the swift electric craft. Not one alone, but dozens of them are skimming gracefully to and fro over the murmuring waters of the purple lagoons. The hallucination of the spirit land is fading now. We are coming slowly back to terra firma, but are no less enraptured with the wonders evolving before us.

The Court of Honor at Night. [Image from Johnson, Rossiter A History of the World’s Columbian Exposition Volume 1 – Narrative. D. Appleton and Co., 1897.]

In Golden Splendor

Our eyes follow the swift electric launches down toward the lake. The first thing that arrests our attention on the way is the massive statue of the republic. There she stands in all her golden splendor, a guardian angel protecting the children of her domain, “Vita brevis, ars louga,” we murmur softly and let our eyes wander down to the white peristile [sic], which at once strikes the beholder with its majestic classic bearing. The unique pillared archways, the long rows of heroic statuary, which adorn the upper promenade and the great Quadriga crowning the triumphal arch in the center makes us feel that we are living in the days of ancient Greece, and we confidently expect some of the old poets or gladiators [1] to step down the long colonnade and address us in the impressive Grecian tongue. The illusion is so beautiful that awakening can but bring disappointment. At our right stands the magnificent “Palace of Agriculture,” with its mammoth Corinthian columns, exquisite statuary and artistic glass dome [2]; while to crown all—twirling in fantastic graceful beauty high in the air—we see Diana, the mythological queen of the night. These words of the poet [3] come to our mind.

“Fair Diana, goddess of the chase,

Whose shafts unerring fly,

Sole sovereign of the female race,

Nocturnal empress of the sky.”

Sailing far above her in triumph, and looking down with pale, silvery eyes from her “Cloud Palace,” Diana’s queenly soul majestically rides the heaven.

Illumination of the Court of Honor. [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

Winslow Homer’s The Fountains at Night, World’s Columbian Exposition (1893) [Image from the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine, Bequest of Mrs. Charles Savage Homer, Jr.]

The Goddess of the Court

Truly America should be proud to claim the man [4] whose inspired genius could conceive so beautiful and impressive a structure of art. Can there be a man, woman, or child who looks upon it so lacking in appreciation as to pass it by and call it purity? If so, we give them heartfelt sympathy. Each figure in the construction tells a story all its own and teaches a life lesson. If you have never studied this work of art and science, do so at once, that it may live in your memory ever. But one thought in connection with it causes sorrow and regret—that is, that so soon it must crumble into dust. We would christen Columbia the Glorious Goddess of the Court, and bid Prometheus bring fire from heaven to make her immortal. We would have her surrounded ever by Triumph, Time, Fame, Art, Science, Industry, Progress, Commerce, and Youth. [5] We would have the tritons, dolphins, and water sprites forever sporting at her feet. The mad sea-horses plunging in wild fury through the waters before her, and the dazzling search-lights ever crowning her with celestial purity and grandeur. But it may not be, so here, “A la belle etoile,” we will say “adieu,” while sadly we bow our heads and think, “So goes the world,” “Aujord hui roi demain rein.” Some hidden impulse after this impressive study causes us to glance in the direction of the “obelisk.” The charm is broken. We recoil in horror at sight of the tall, ghostly pyramid [6] so suggestive of ruin and vanished glory. We look about us uneasily to see if we are sitting when it casts its long, black shadow. Lonely, silent, gloomy, and uncourted, it towers amid the splendors of the magic circle. It stands a monument to the art, science, and labor of all nations, and should command respect. But no one cares to visit it. No friendly light sheds radiance upon it. No soft-voiced lovers exchange eternal vows of constancy in the wake of its weird, unearthly shadows. It seems an ill-omened messenger in a land of poetry and dreams. We are seized with a sudden desire after this to move.

Jules Guerin’s watercolor “The MacMonnies Fountain by Night.” [Image from Bancroft, Hubert Howe The Book of the Fair. The Bancroft Company, 1893.]

On the Water

The spirit of unrest seems to have taken possession of us, so we saunter in a half-dazed way down to the water’s edge, pay our 50 cents and step into a real Venetian gondola, just such as one as we have dreamed of since childhood. There are many-colored lanterns hanging in picturesque lines and clusters, forming a sort of glittering canopy, exactly as our fancy painted them. We lean over the edge of the boat and watch the reflections dancing in soft ethereal beauty upon the surface of the dark waters. There stands the very black-eyed, swarthy gondolier, clad in his picturesque garb of red and white, with the blue sash knotted at his side, that figured ever in our dreams. No sound save the dip, dip, dip of his oar in the water breaks the enchanting stillness. Gayley illuminated gondolas are gliding noiselessly like bright-plumaged birds hither and thither all about us. How easy ’tis to close our eyes and imagine ourselves in the midst of a Venetian carnival floating by the weather-stained palaces, famed in poetry, song and history. Our mind revels in romance; our soul is intoxicated with the delicious aroma wafted fresh from the “wine of the gods.” Hark! Soft as the trill of a nightbird the clear notes of an old Italian love song breaks through the air. ’Tis the dark-eyed gondolier. How sweetly his voice echoes and re-echoes up and down the lagoons, dying softly away over the unseen waters of the night-buried lake. “Amoroso,” we murmur, for there was a sound as of unshed tears in his voice that made us sigh in sympathy. Ah! He was singing to his love in far-away, sunny “Italia.” It is complete. We have visited the poetic queen of the Adriatic and glided through her Grand canal on a carnival night. We have seen our gondolier and listened to his song, or at least, “Se non e vero a ben travato.” So now we will say, “A vive derci.” [sic]

Charles S. Graham’s watercolor “Moonlight on the Lagoon.” [Image from Graham, Charles S. The World’s Fair in Water Colors. Mast, Crowell & Kirkpatrick, 1893.]

The illusion is perfect. The vision is seraphic, but it fades all too soon. While from the depths great troubled streams of glowing purple leap, dash and gurgle in wild fury through the air. Imagination takes a stronger hold upon our mentality. The streams grow darker and leap higher and higher. From the rocky purple cave rises Pluto and his fiery steeds. He reaches out his great, brawny, muscular arms in triumph, and lifts the fair Persephone from the light above into the car beside him and sinks through the purple shades quickly to the rocks.

“Oh, light, light, light! She cries farewell,

The coal-black horses carry me.

Oh, shade of shades where I must dwell

Demeter, mother, far from thee.”

She is gone, gone to rule queen of Philo’s domain.

Ah! shimmering, glinting grotto of emerald green, Neptune, clad in his robes of shining scales, a jeweled scepter in his hands, sits a monarch on a crested throne. All about him through the transparent waters float sea nymphs, tritons, mermaids and mermen, while long rows of green-haired naiads, adorned with flashing diamonds, are seen climbing up the mystic, foamy stairs. Some are lounging at his feet; others are twining his neck and crown with bejeweled garlands. To our deluded eyes the scene is realistic; it is beautiful in the extreme, this inhabited glittering grotto overflowing with emerald waters, but it as fleeting as the previous visions. We are just about to come back to this mundane sphere once more, when “Aurora” dances gayly forth, attended by all her sylphs and maidens. She just touches the floodgates of dawn with her dainty finger tips and instantly “couleur de rose” fills the air. Backward and forward, up and down, the merry maidens dance and flirt in many a gay and fantastic whirl of rhythmic beauty. Then the grand, the glorious Apollo rides forth in his great golden sun chariot, driven by Heloise, the sun god. For one brief instant the soft rose tints blend with shining gold, then the merry maidens far below him, floating in the pink spray, throw sweet kisses as he rides over the arch of the heavens on his journey westward.

Oh, those ethereal, electric fountains! Who can watch them without weaving fancies while they play? This grand Court of Honor—no pen or word picture can do it justice. Your eyes must behold the glories. “Quand on voit la chose, on la croit.”

Charles Curran’s “Administration Building and Electric Fountains at Night” [Image from Hitchcock, Ripley The Art of the World Illustrated in the Paintings, Statuary, and Architecture of the World’s Columbian Exposition. D. Appleton, 1895.]

NOTES

[1] “gladiators” Gladiators were part of the culture of ancient Rome, not Greece.

[2] “glass dome” While the Horticultural Building on the Lagoon had a glass dome, the dome of the Agricultural Building, surmounted by the statue of Diana, was not glass.

[3] “the poet” The poem Knapp quotes appears to be from A Translation of Jacob’s Greek Reader by Friedrich Jacobs and Patrick S. Casserly (W. E. Dean, 1842), a work that likely would have been familiar to an elocution teacher.

[4] “claim the man” The sculptor, unnamed by Knapp, is Frederick MacMonnies. His triumphant Columbia Fountain was commonly called the MacMonnies Fountain.

[5] “surrounded ever by” Knapp has jumbled the character names. The barge was oared by the Arts and Industries. The rowers on the right side were Music, Architecture, Sculpture and Painting, while those on the left side were Agriculture, Science, Industry and Commerce. Steering the barge at the helm with his scythe was Father Time.

[6] “the tall, ghostly pyramid” Knapp’s Freudian fear is directed at the Obelisk in the South Canal.

SOURCES

Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, NY) Sept. 28, 1899, p. 7.

“Penelope Gleason Knapp” Werner’s Magazine May 1893 p. 168.

“Mrs. Gleason Knapp” Penn Yan (NY) Democrat Oct. 31, 1924.

The Pensacola (FL) Journal, Dec. 7, 1919, p. 6.

Werner’s Voice Magazine Sept. 1891 p. 332.

Werner’s Magazine Apr. 1893 p. 142-43.

Werner’s Magazine Nov. 1899 p. 326.

Yates County Chronicle (Penn Yan, NY), Sept. 8, 1915, p. 5.